Culture

‘Make the complex simple’ and adapt on the fly: How Kevin O’Connell leads electric Vikings

Long after Los Angeles Rams practices in the late summer of 2021, Kevin O’Connell lingered on the field in a huddle with head coach Sean McVay, receiver Cooper Kupp and quarterback Matthew Stafford. Sweat poured off of each man and dripped into the grass as the players scuffed at it with their cleats. They gestured and debated with one another, the coaches writing notes on salt-slicked play cards.

McVay’s offense led the NFL when he became the youngest head coach in league history in 2017, but it had stalled over the previous two seasons. He and O’Connell were rebuilding it together.

O’Connell, a former star quarterback at San Diego State and then an NFL journeyman, translated Stafford’s 12 NFL seasons of football knowledge and married elements of what worked with McVay’s playbook. The head coach was drawn to O’Connell’s creativity and understanding of quarterbacks when he hired him as offensive coordinator in 2020, and after trading for Stafford in 2021 they charted new schematic territory.

Every day that summer was about adjusting tiny details with Stafford and Kupp. O’Connell wanted to prepare them for any potential problem a defense might present. “You try to give them the answers to the test before they have to take it,” he told The Athletic this summer. “There’s no such thing as a great game plan without the ability to adapt on the fly.”

In Super Bowl LVI, they all lived that.

McVay, battling an illness in the days leading up to the game, grew hoarse at times, so O’Connell quietly prepared in case he might have to actually call the game. He was also deep in the interview process with the Minnesota Vikings for their head coaching position. Star receiver Odell Beckham Jr. was supposed to be the central element of the passing game against the Cincinnati Bengals but went down before halftime with a knee injury. No. 3 receiver Van Jefferson was playing hurt, and running back Cam Akers had just returned from an Achilles repair. The ground game wasn’t working. Stafford’s cast of skill players had changed dramatically from the first quarter, and so too had the Rams’ game plan.

It was, some players and executives recalled, as if McVay, O’Connell, Kupp and Stafford had resorted to drawing up plays on the sideline in the second half.

Late in the fourth quarter, the Rams’ fate hinged on a player who had hardly ever seen the field. Down four points, the offense faced fourth-and-1 from their own 30-yard line. Voices flooded into a wide-eyed McVay’s headset as he prepared the call.

Stafford and Kupp were about to run a play that had failed when they tried it together in practice over the two weeks of preparation for the game, a play they workshopped all the way up to the bus ride to the stadium. It was a sweep handoff to Kupp that started with a stutter-step motion from the left side of the formation. Kupp was supposed to cut the sweep short after he got the ball in order to scoot behind a crucial block on the right edge, then get upfield through that hole.

The block now would be assigned to second-year tight end Brycen Hopkins, a former fourth-round pick who was only in the game because the starters and backups were injured. There was no time to doubt whether he could do it.

It worked. The handoff, the block, the improbable conversion became one of the defining plays of the Rams’ championship.

O’Connell realizes now, as a third-year head coach whose 4-0 Vikings are the talk of the league, how similar the last two quarters of the Super Bowl were to the hot, grueling days of training camp. Then, he would sometimes daydream about one day installing his own offense as a head coach. He thought about the language he would use, how he would collaborate with his own assistants and players, how he would create answers to their questions.

Hours after winning the Super Bowl, O’Connell accepted Minnesota’s head coaching job. Later that week, he stepped off a parade bus sticky with beer and confetti and into his future. He brimmed with positivity, a sunbeam pouring into Vikings offices still cloaked in winter.

O’Connell had a vision. He had a plan. He had a playbook and a sound teaching process.

Yet he couldn’t have predicted how often he’d be reminded of football’s inherent chaos — and how crucial his knack for adaptation would be — over the next two seasons.

O’Connell’s young children are really into Legos. He and his wife, Leah, have a massive tub in their home containing hundreds of the little multi-colored bricks from dozens of separate sets.

The tub has no rules, nor order — the manuals for each set were thrown out long ago. The kids grab pieces — a couple of blocks from a disassembled “Cars” character, a few more from a “Star Wars” ship — and build whatever is in their imagination.

It drives O’Connell a little nuts. Building something real requires a plan, and part of him wants to know what all of the pieces do, or the different ways they might fasten to each other, before he starts to build. But the other part of him loves that his kids are having a blast creating like this, so he happily sits on the floor and fastens a racecar tire to a TIE Fighter.

He admits his two most dominant qualities — obsession with process and detail, and empathy — compete with one another, but in an NFL quarterback room one is needed just as much as the other, often at the same time. It’s why O’Connell’s teaching method has resonated with players.

As a play-caller, Kevin O’Connell specializes in providing answers for his players. (Stephen Maturen / Getty Images)

With quarterbacks, he implements a layered approach that first explains why a play or broader concept will manifest in a certain way. This defense has a rule that says they’ll react to this formation with this type of coverage, so we will change our formation spacing to force them out of their rule and create our advantage instead of, we are lining up this way.

O’Connell installs a core alphabet for his system. Then he builds out the playbook and week-to-week game plans by tying a word players recognize in a concept or play to another word which brings them into a family of plays and eventually grows into an entire system. The player can easily jump between plays within a family and into the broader system because the words he recognizes escort him there. The point is to avoid rote memorization; everything links to something else. O’Connell calls it “dot-connecting.”

“Maybe it’s a concept that you take from an existing concept, and you say, ‘Here’s how we’re gonna change it, here’s how we’re gonna name it,” O’Connell explained. “It’s in a family of names that have sameness and likeness — big cats, sports cars — whatever it is, you name it, we’ve got a category for it. And if we don’t, we’ll have one soon enough.”

O’Connell asks his players for detailed feedback during the installation of his offense and subsequent practices. If a receiver feels more comfortable adjusting his route off a third inside step instead of a fourth, or if the quarterback wants to swap out one route for another while attacking the same space on the field, O’Connell changes his play.

“I’m not the one out there running the play,” O’Connell said. “If it doesn’t infringe upon the play-caller’s intent or the design of the play, ‘It’s yours, guys.’ I think that there is power in that, in this day and age … when they feel like they are a voice at the table, not just someone being talked to.”

“The way he connects, the way he talks with us, the way he understands us as players, I feel like it’s a really good characteristic as a coach,” said Vikings All-Pro receiver Justin Jefferson.

Plus, when players feel like they have a say in the details of the plays they run, O’Connell is comfortable asking them to trust him when he adjusts the plan in real-time. He does this often and for good reason. Defenses come up with bespoke plans — at times outside their typical system — to try to slow down Jefferson. There sometimes is no precedent for how a specific opponent will try to mitigate him until they show their strategy in a game’s first few series.

When that happens, O’Connell and his staff workshop their own offensive counters on the sidelines and in the locker room at halftime. They come up with a list of “what-if’s”: If a defense does X, how will the Vikings respond?

“I think the best coaches see it live. They can make those in-game adjustments, they don’t have to wait until after the fact to do that,” said McVay, who watches cut-ups of Minnesota’s game film every week. “I’ve seen Kevin do that in his tenure there.”

O’Connell’s adaptability beyond game-planning has been tested. While his 2022 team won 13 games — 11 by one score — they were ultimately undone by a defense that ranked near the bottom of the league and lost in the wild-card round. To fix it, O’Connell hired former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores, known for his complicated, aggressive, pressure-diverse scheme. A former quarterback hired a modern quarterback’s biggest fear.

GO DEEPER

How Brian Flores and the Vikings built such a ‘wild’ and ‘different’ NFL defense

The Vikings lost their first three games in 2023, but just as veteran quarterback Kirk Cousins and the offense began to find their rhythm and put together a string of wins, chaos struck again.

Cousins tore his Achilles against the Green Bay Packers in Week 8. Minnesota traded for journeyman Josh Dobbs, but after starter Jaren Hall suffered a concussion the following week, O’Connell was essentially forced to install a playbook for Dobbs on the fly. The Vikings won that game and the next, but Dobbs’ production did not last. Minnesota rotated quarterbacks through the last several games of the season, and O’Connell stretched himself thin managing the different players and game plans while keeping the building encouraged about the future.

“It speaks to the whole of building a culture, systems, schemes, how he works with people, how he creates an environment for guys to grow together,” game management coordinator and pass game specialist Ryan Cordell said. “Last year, we’re battling injuries, and he didn’t change. He was the same guy.”

The Vikings parted with Cousins in free agency last summer with the plan to draft and develop their next quarterback. They also signed free agent Sam Darnold, the third pick in the 2018 draft who pinballed from dysfunctional to dysfunction until he repaired his bad habits and nursed his bruised confidence last season in San Francisco.

O’Connell leveled with Darnold and Vikings fans after Minnesota selected Michigan star J.J. McCarthy with the 10th pick in April’s draft. While McCarthy would be the future, O’Connell would still do whatever he could to help Darnold compete for the starting role in 2024 on a one-year deal, to reset the narrative and give him tools to help fulfill the potential many believed he’d never reach. All the better if that gave McCarthy — who, at just 21 was the same age as Darnold when the New York Jets drafted him — more time to develop as an NFL player.

O’Connell structured most of the first-team summer reps around Darnold to help him adjust to his new system while gradually increasing McCarthy’s workload and preparing him to play in the preseason. O’Connell was mulish that he would not put McCarthy in a position he wasn’t ready for — at times bristling at questions about the rookie’s timeline.

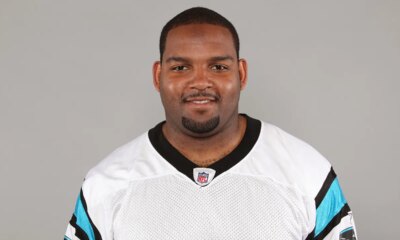

A third-round pick of the Patriots in 2008, O’Connell’s NFL playing career fizzled out before it ever really began. (Jim Rogash / Getty Images)

That adamance (and how O’Connell expressed it) stemmed from his own tumultuous experience as an NFL backup. He understood how quickly a quarterback’s vibe can sour. O’Connell was an athletically gifted and smart prospect when he was drafted by the Patriots in the 2008 third round to back up Tom Brady. But New England cut O’Connell in 2009 and he bounced around several teams for the next three years, with a labrum surgery thrown in for good measure in 2010.

He used to view his playing career with some regret, but that perspective has shifted, especially as he got into coaching. He studied behind a future Hall of Famer in Brady and alongside blossoming young stars such as Stafford and shared position rooms with amiable teammates like Matt Cassel and Mark Sanchez. O’Connell understood what a young quarterback can learn when a position room is built thoughtfully. His experience ultimately helped inform him as a teacher and a manager of people.

That was also part of why the Vikings brought in Darnold — to show McCarthy what pro preparation and study habits look like, to give him a collaborator and to make sure a uniquely isolated position did not feel that way.

“I think back on different interactions and being able to be around some great players, coaches and humans throughout my NFL journey. I think about how I can shape our team, and my messaging to our team and our quarterbacks, to really do two things: challenge them but ultimately let them know that I have their backs and that everything I’m trying to accomplish is for them in conjunction with them achieving success,” O’Connell said.

On July 6, Vikings rookie cornerback Khyree Jackson was killed in a car accident in Maryland. “It has been a significant time in our organization, losing a player,” O’Connell said. “You are personally working through your process of dealing with something like that — while also knowing that my role is to be there… for anyone that might need support, and love, and guidance.”

Players were away from the facility during the brief break in the NFL’s calendar. O’Connell got on the phone with anybody who needed to talk, checking on players and coaches and grieving privately.

“He has a heart for people,” said McVay. “He really pays close attention to what people need, (and) he’s that for them.”

The Vikings contributed $20,000 to funeral expenses and paid out Jackson’s signing bonus to his estate. O’Connell spoke at the funeral in Jackson’s hometown, and the team also had a private memorial service with Jackson’s family in Minnesota. They keep Jackson’s locker open, and players wear decals of his initials on their helmets. O’Connell wears a pin above his heart that says “KJ.”

O’Connell told the team what he had learned through two years as a head coach and decades as an assistant and player before that: Life is a combination of success, adversity and chaos. They would all mourn as football’s unforgiving clock ticked on.

The season approached. In August, after the Vikings’ first preseason game, McCarthy tore his meniscus. His rookie season was over before it began, and for a moment, the injury soured Minnesota fans’ hopes for 2024.

But O’Connell believed in Darnold.

O’Connell’s belief in Sam Darnold (right) has manifested in Minnesota’s 4-0 start to the season. (Stephen Maturen / Getty Images)

The Vikings are 4-0 with wins against postseason favorites like the San Francisco 49ers, Houston Texans and Packers. Darnold is playing better than ever. He has thrown for 932 yards and a league-leading 11 touchdowns with three interceptions while completing 68.9 percent of his passes. He also ranks third in the NFL in completion percentage above expectation (5.7), a measurement that takes into account the situational context of a passing play.

O’Connell’s fingerprints are all over Darnold’s renewed confidence and resurgent play, which has featured help from a steady run game, skilled receivers and Flores’ No. 1-ranked defense. But O’Connell doesn’t smother the young quarterback. Instead, he provides Darnold with multiple answers on every play, giving him a manual and an understanding of how the pieces might fit together.

Against the Giants in Week 1, a 22-yard pass to tight end Josh Oliver was designed to give Darnold two options depending on how the defense covered Jefferson. If New York’s defense stuck to its system’s rules for the concept and personnel the Minnesota offense showed, a safety and extra linebacker would flow toward Jefferson’s route, leaving Oliver open up the right hash if he got behind just one other linebacker. If the defense “broke” its own rules for that look, Jefferson would be wide open.

“With the proper amount of structure, coaching and clarity that you can give these players, you can make this very difficult or you can make the complex simple,” said O’Connell. “You’re constantly trying to find that balance, and the balance is in how you’re coaching it. I never want to be a Monday morning ‘clicker coach’ where I am holding the clicker … saying, ‘You should have done this, this and this.’ If I’m saying those things, I probably didn’t coach it very well.”

Perhaps Darnold’s true “arrival” this season came on a third-and-9 pass in a Week 2 win against the 49ers after Jefferson left the game with a quad injury. Darnold threaded a pass to receiver Jalen Nailor between three defenders, letting the ball go at the perfect moment where a fraction early or late would have almost certainly led to a turnover.

In that game, Darnold threw for 268 yards and two touchdowns plus an interception and ran for 32 yards. His 97-yard touchdown pass to Jefferson was so electric that O’Connell sprinted down the sideline to celebrate, headset cord streaming behind him like a banner.

“The amount of work that goes into that position, on your quarterback journey, when everybody decides that you cannot play … ” O’Connell said after the game. “We always believed in him. Awesome to watch him go do that thing. I am really proud of Sam Darnold.”

O’Connell fought to control his voice, but it cracked with emotion as he thought about a young quarterback who got another chance and what he was building with him.

(Illustration: Meech Robinson / The Athletic; photos: Adam Bettcher, Nick Cammett, Stephen Maturen/Getty Images)

Culture

Try This Quiz on Thrilling Books That Became Popular Movies

Welcome to Great Adaptations, the Book Review’s regular multiple-choice quiz about printed works that have gone on to find new life as movies, television shows, theatrical productions and more. This week’s challenge highlights thrillers first published as novels (or graphic novels) that were adapted into popular films. Just tap or click your answers to the five questions below. And scroll down after you finish the last question for links to the books and their screen versions.

Culture

Test Your Knowledge of the Authors and Events That Helped Shape the United States

Welcome to Lit Trivia, the Book Review’s regular quiz about books, authors and literary culture. In honor of Gen. George Washington’s birthday on Feb. 22, this week’s super-size challenge is focused on the literature and history related to the American Revolution. In the 10 multiple-choice questions below, tap or click on the answer you think is correct. After the last question, you’ll find links to exhibits, books and other materials related to this intense chapter in the country’s story, including an award-winning biography of the general and first U.S. president.

Culture

Video: How Much Do You Know About Romance Books?

Let’s play romance roulette. No genre has dominated the books world in the last few years. Like romance, it accounts for the biggest percentage of book sales, their avid fan bases. Everyone has been talking about romance as a Book Review editor and as a fan of the genre myself, I put together a to z glossary of 101 terms that you should know if you want to understand the world of romance are cinnamon roll. You may think a cinnamon roll is a delicious breakfast treat, but in a romance novel, this refers to a typically male character who is so sweet and tender and precious that you just want to protect him and his beautiful heart from the world. Ooh, a rake. This is basically the Playboy of historical romance. He defies societal rules. He drinks, he gambles. He’s out on the town all night and is a very prolific lover with a bit of a reputation as a ladies’ man. FEI these are super strong, super sexy, super powerful, immortal, fairy like creatures. One of my favorite discoveries in terms that I learned was stern brunch daddy. A lot of daddy’s usually a male love interest who seems very intimidating and alpha, but then turns out to be a total softie who just wants to make his love interest brunch. I think there’s a misconception that because these books can follow these typical patterns, that they can be predictable and boring. But I think what makes a really great romance novel is the way that these writers use the tropes in interesting ways, or subvert them. If you can think of it, there’s probably a romance novel about it. Oops, there’s only one bed. This is one of my personal favorite tropes is a twist on forced proximity. Characters find themselves in very close quarters, where inevitably sparks start to fly. Why choose is the porkulus dose of the romance world. Sometimes the best way to resolve a love triangle is by turning it into a circle, where everyone is invited to play. Oops, we lost one spice level. There’s a really wide spectrum. You can range from really low heat or no spice, what might also be called kisses. Only then you start to get into what we call closed door or fade to Black. These books go right up to the moment of intimacy, and then you get into what we call open door, which is more explicit. And sometimes these can get very high heat or spicy and even start verging into kink. There’s one thing that almost every romance novel has in common. It’s that no matter what the characters get up to in the end, it ends with a happily ever after. I say almost every romance novel. Sometimes you’re just happy for now.

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making