Business

The Vaccine Mandate Remains at Some New York City Restaurants

On Tuesday evening, about 20 individuals descended on Dame, in Greenwich Village, to protest the restaurant’s request that indoor diners present proof of vaccination, a day after the town dropped its vaccine mandate.

5 males entered the tiny seafood restaurant and wouldn’t go away, whereas others, angered by the restaurant’s resolution to proceed to ask for proof of vaccination, crowded exterior, stated Patricia Howard, an proprietor. The police have been known as a number of occasions, she stated, and a neighboring restaurant, Carbone, despatched a safety guard to assist them make a safety plan.

“They’ve each proper to protest exterior on the road,” stated Ed Szymanski, the restaurant’s chef and an proprietor. “I simply don’t need them to be threatening workers and trespassing on personal property. In the event that they need to stand exterior with picket boards, be our visitor.”

When the town on Monday ended its requirement that eating places ask indoor diners for proof of vaccination, it left it as much as house owners to determine whether or not to voluntarily proceed these requests. And a few eating places, like Dame, usually are not able to let go of the security measure, which they see as a approach to defend their prospects and workers.

The incident at Dame started round 8 p.m., when Ms. Howard requested two males to go away. That they had arrived with no reservation and the restaurant was totally booked, she stated, including that the lads didn’t present proof of vaccination and tried to sit down on the bar. The boys finally left, however returned with different individuals and the protest started.

New York’s transfer to finish the vaccine requirement, one of many nation’s most restrictive, was a part of a broader effort to reopen the town, whose economic system continues to be struggling, and to deliver again a way of normalcy after the speed of recent Covid-19 circumstances dropped, stated Mayor Eric Adams. The announcement got here as different cities, like Philadelphia, and states ended their mandates. On Feb. 10, Gov. Kathy Hochul ended a statewide rule that indoor companies require masks or proof of vaccination.

The mandate was launched final August by Mr. Adams’s predecessor, Invoice de Blasio. Some eating places within the metropolis and throughout the nation had established their very own guidelines weeks earlier than, throughout a surge of the Delta variant.

Some restaurant house owners, like Ms. Howard of Dame (one of many first locations in New York Metropolis to ask diners for vaccine playing cards), are actually nervous in regards to the potential for disorderly friends who’re upset about vaccines. She felt the mayor’s ending the vaccine requirement was a sign that eating places don’t have the town’s assist. “It seems like we’re now on our personal,” she stated.

Different house owners stated they concern that by loosening necessities they may find yourself again the place they began if there are new Covid variants or surges.

“At this level in our lives, we really feel that small strikes are higher than giant strikes,” stated Marc St. Jaques, the working proprietor and chef of Bar Bête, a restaurant in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, who stated the managers determined to proceed the vaccine requirement after assembly together with his workers, which supported the mandate. “We go little by little to determine what the perfect factor is.”

The restaurateurs stated the vaccination requirement can hold workers from getting Covid and lacking work, or forcing the restaurant to shut, as many needed to do when the Omicron variant surged this winter.

“Everybody wants cash with a purpose to survive, however I care about my workers greater than something,” stated Kyo Pang, the proprietor of Kopitiam, a fast-casual restaurant serving Nyonya delicacies on the Decrease East Aspect. Earlier than deciding to increase the restaurant’s vaccine requirement, she met with the workers, who supported the transfer. “We needed individuals to really feel like that is their second residence.”

For Sivan Harlap, a restaurateur on the Decrease East Aspect, requiring proof of vaccination has helped her regulars at Eastwood and the Dancer really feel extra snug eating out, she stated.

“We really feel like our group prefers to be in an area indoors the place most or all are vaccinated,” she stated. “It’s the factor that feels proper to us.”

Business

Car-sharing app Turo defends security standards after New Year's attacks

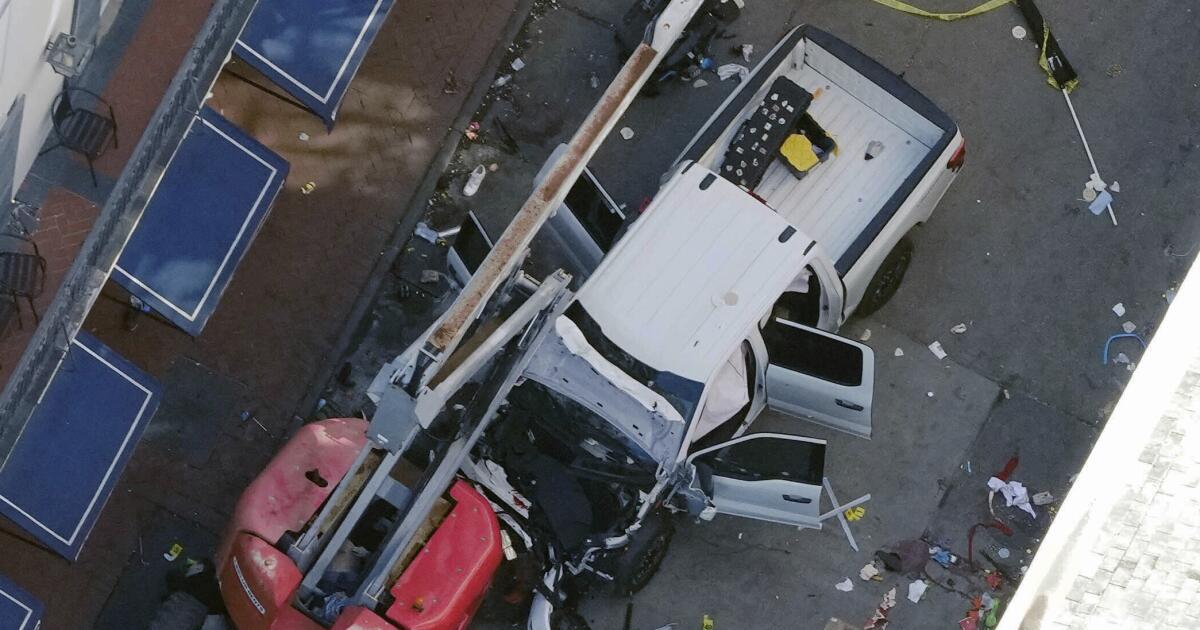

Both the vehicles used in two New Year’s Day attacks in New Orleans and Las Vegas were rented through Turo, a car-sharing app.

The attacks thrust the San Francisco company that created the app, which relies on a model similar to Airbnb to enable users to rent cars directly from their owners, into the spotlight and raised questions about the ability of such peer-to-peer services to adequately vet users for possible safety issues.

In a statement, the company defended itself, saying it’s committed to the “highest standards in risk management.”

“We do not believe that either renter involved in the Las Vegas and New Orleans attacks had a criminal background that would have identified them as a security threat,” Turo said in a statement Wednesday. “We are actively partnering with law enforcement authorities as they investigate both incidents.”

In the first incident early Wednesday morning, 42-year-old Shamsud-Din Jabbar plowed a Ford pickup truck he rented on Turo into a crowd on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, killing at least 14 and injuring many others before being killed by police. Later that day, a man authorities believe to be 37-year-old Matthew Livelsberger parked a Tesla Cybertruck he had rented days earlier in Denver in front of the Trump International Hotel in Las Vegas. Seconds later, fuel canisters and fireworks packed into the truck’s bed exploded, slightly wounding seven bystanders. The driver’s badly burned body was later found with a gunshot wound, leading authorities to conclude Livelsberger shot himself.

Founded in 2009 by former Chief Executive Shelby Clark, privately held Turo operates in more than 16,000 cities and serves 3.5 million active guests. The app offers more than 1,600 makes and models of vehicles and has helped vehicle owners earn $4.8 billion since its inception, a company filing said.

The app works by connecting renters to car owners seeking to share their vehicle for a profit. Users can search for cars by location and communicate directly with owners to arrange a pickup. Owners set their daily rates, and there’s a $15 minimum requirement for each trip.

According to the company’s website, a user must have a valid driver’s license, home address and payment card to rent a vehicle. Turo may also check a potential renter’s credit report and criminal background, the website says.

The company said it was “heartbroken by the violence perpetrated” and employs “world-class” trust and safety protocols, including hiring former law enforcement professionals.

Turo claims to be the world’s largest car-sharing marketplace and offers an alternative to traditional rental companies such as Hertz and Enterprise. Founded as a venture-capital-backed startup, the company first filed paperwork to make an initial public offering in 2022 but has yet to go public.

Turo saw a $14.7-million profit in 2023 and $19 million over the first nine months of 2024, according to a filing. It faces some competition in the car-sharing space, including from the rental app Getaround, which uses a similar platform to connect owners and renters.

This is not the first time Turo vehicles have been associated with criminal activity. In 2021, a Houston woman was charged with committing a series of robberies, which she allegedly carried out using seven cars rented through Turo. Rentals from Turo and Getaround have also been stolen and involved in drug trafficking, according to NBC News.

Police have identified suspects in both New Year’s Day attacks. After investigating a possible connection between the incidents, authorities said they believe the two men involved in the incidents each acted alone. The Cybertruck explosion was not due to a faulty vehicle, Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk said.

The owner of the pickup used in the New Orleans attack told the New York Times that he recognized his vehicle on the news. He had been renting out five vehicles on Turo as a second income stream but will not use the platform after the attacks, he said.

Business

Opinion: The IRS faces more cuts under Trump. Here are three ways that could hurt the economy

Donald Trump’s election with Republican House and Senate majorities has put the Internal Revenue Service back in the spotlight. The agency lost $20 billion in funding under the latest deal to avoid a government shutdown, and further cuts to its enforcement budget are likely in the next Congress.

Democrats denounce such moves as harmful to federal revenues and tax fairness; Republicans cheer them for limiting government. Unfortunately, neither side tends to point out that an adequately funded IRS is good for the U.S. economy.

Years of IRS underfunding have led to a massive unpaid tax bill, around half a trillion dollars a year. Beyond lowering revenues, the sheer magnitude of this tax evasion has implications across the economy, providing competitive advantages to those able and willing to avoid their tax obligations. Less enforcement funding will only worsen this problem.

The hundreds of billions of dollars in taxes that haven’t been paid are not spread evenly across taxpayers. They’re disproportionately owed by businesses with the greatest incentive and ability to shirk their tax burdens. These include self-employed entrepreneurs, businesses that deal in cash and large, private companies with complex operations. Companies that have less opportunities to evade taxes, and workers who are paid directly by an employer, are more likely to pay their taxes.

The unpaid taxes therefore work as a substantial subsidy for the businesses and taxpayers who evade them. In economic terms, lower taxes boost returns on investment for the businesses that avoid their obligations but not for others. That in turn distorts the way businesses operate in three primary ways.

First, the tax gap pushes more economic activity toward industries and occupations with opaque sources of income — such as construction businesses that deal mainly in cash. Our economy needs contractors, of course, but we don’t want an inordinate number of capable workers rushing into remodeling for cash simply because it offers an illegal tax break. Similarly, we don’t want people choosing self-employment simply because it gives them better chances of dodging the IRS. Labor and capital markets work best when they’re driven by business considerations rather than tax evasion.

Second, tax-cheating businesses gain an advantage on each dollar of profit. A company that doesn’t pay taxes can take on investments that wouldn’t make financial sense if it were meeting its tax obligations. This means the scofflaw company can profitably expand while the complying company cannot, putting honest taxpayers at a competitive disadvantage.

Third, a portion of the economy is dedicated to the evasion itself. Skirting a tax bill can be a lot of work: It takes time and money to set up shell companies, safely store large amounts of cash and falsify documents. Rather than going to some productive use, this activity amounts to what economists consider a “deadweight loss” that does not help our economy expand in any way. Avoiding half a trillion dollars in taxes requires a lot of work and resources that serve no purpose other than to illegally lower tax bills.

The end result of widespread tax evasion is an economy that is far less efficient than it could be. Too many employees in cash-based industries, too many accountants setting up shell corporations and other distortions ultimately discourage investment by taxpaying businesses and suppress economic growth.

Providing the IRS with enough funds to enforce our nation’s tax code isn’t just about fairness and revenue. It’s also vital to the efficiency and productivity of our economy.

Ben Harris is the vice president and director of economic studies at the Brookings Institution and a former assistant Treasury secretary for economic policy.

Business

Column: A Faulkner classic and Popeye enter the public domain while copyright only gets more confusing

Last year, it was Mickey Mouse. This year, Popeye the Sailor joins Mickey as a new entrant to the public domain — that is, shedding his core copyright protections on Jan. 1.

He’s merely the most familiar cultural artifact to enter the public domain on Wednesday. But as Jennifer Jenkins, co-director of Duke University’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain notes in her indispensable annual roster of newly public works (posted this year with co-director James Boyle), Popeye’s initial appearance in print is among thousands of culturally and artistically significant works to become copyright-free. That means they become available for anyone to copy, share and expand upon without paying their creators for rights.

This year’s treasure trove includes literary works originally published in 1929, meaning their 95-year copyrights expire on New Year’s Day. They include William Faulkner’s novel “The Sound and the Fury,” in which he began to perfect his literary style and his gloss on racial and social stratification in his native Mississippi; Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms”; and Virginia Woolf’s essay “A Room of One’s Own.”

Community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can perform the music publicly, without paying licensing fees. Online repositories … can make works fully available online. This helps enable both access to and preservation of cultural materials that might otherwise be lost to history.

— Jennifer Jenkins, Duke University, on the value of the public domain

There are also Dashiell Hammett’s “The Maltese Falcon,” originally published as a serial in Black Mask magazine, and John Steinbeck’s first novel, “Cup of Gold.”

Among films, the haul includes the Marx Brothers’ first movie, “The Cocoanuts,” which was based on a George S. Kaufman Broadway musical and betrays its stagebound genesis in almost every scene; Alfred Hitchcock’s first sound film, “Blackmail,” and an early film adaptation of Edna Ferber’s “Show Boat” — a 1929 version of Ferber’s novel, not the musical version, which was filmed in 1936 and, more familiarly, in 1951.

Interpretations of copyright law haven’t been as divergent as they’ve become over the last year or two. The reason is AI, or at least the development of AI bots “trained” on copyrighted written, musical and artistic works. Numerous lawsuits brought by creators are making their way through the federal courts.

AI developers generally claim that their feeding copyrighted works into their bots’ databases falls within the “fair use” exception to copyright protection. The fair use doctrine, as the U.S. Copyright Office puts is, allows the use of “limited portions of a work including quotes, for purposes such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, and scholarly reports.”

Whether a particular use qualifies “is notoriously fact-specific,” Jenkins told me. “So it’s hard to shoot a straight arrow through all the cases,” in part because the judgment of whether a use is exempt from copyright depends on whether creators can show that the use caused harm to the market for their works.

“It’s a wild patchwork of cases,” Jenkins says, “but the central issue to all is the same, namely is it fair use to train your AI model on copyrighted content, but the specifics vary. Often I have something resembling a prediction of how fair use cases are going to come out, but really cannot predict which way these cases are going to go. It’s a moving target in copyright land.”

This isn’t the first time that technological change has roiled the copyright landscape. One precedent is the Google Books case, in which authors and publishers sued Google to block its effort to create a searchable database of written works by digitizing copyrighted works along with works in the public domain.

The ultimate settlement allows Google to digitize books for the database, but to display only limited “snippets” of copyright-protected works to users — enough to enable users to search for specific words or phrases, but not to access significant portions of the works.

Also entering the public domain this week, as Jenkins observes, are about a dozen Mickey Mouse films, including one in which he speaks his first words (“Hot dogs! Hot dogs!”) and wears his iconic white gloves. That depiction of Mickey is now copyright-free; the ur-Mickey depicted in the Walt Disney short “Steamboat Willie” entered the public domain on Jan. 1, 2024, but later depictions such as the white gloves were still subject to copyright restrictions based on when they first appeared on film.

Popeye first appeared as a peripheral character in January 1929 in E.C. Segar’s “Thimble Theatre” comic strip. He garnered such instant popularity that Segar eventually refashioned the strip around him. Some story elements, such as the role of spinach as a source of his superhuman strength, became part of his persona over subsequent years.

Popeye also gives us a window into how a character’s entry into the public domain doesn’t require subsequent exploitations to adhere to his or her original conception.

Los Angeles copyright attorney Aaron Moss observes in his own curtain-raising post about public domain day 2025 that several Popeye-inspired horror films, “including ‘Popeye the Slayer Man,’ set in an abandoned spinach cannery, and ‘Shiver Me Timbers,’ featuring a meteor that ‘transforms Popeye into an unstoppable killing machine,’” have already been announced.

Similarly, er, disrespectful treatments of Mickey Mouse and Winnie-the-Pooh (a member of the public domain class of 2022) have been produced or announced.

The copyright rules for music are particularly convoluted. “Fats” Waller songs including “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue” are entering the public domain, which should help to augment Waller’s reputation as a jazz and Broadway innovator. So too are George Gershwin’s “An American in Paris” and the popular standards “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” (lyrics by Alfred Dubin, music by Joseph Burke), “Happy Days Are Here Again” (lyrics by Jack Yellen, music by Milton Ager) and “What Is This Thing Called Love?” by Cole Porter.

But as Jenkins notes, only the compositions — what appears on the sheet music — and not any particular recordings are entering the public domain. So the version of “Tiptoe” recorded by Tiny Tim, which made that artist a popular star in 1968, is still under copyright.

“Singin’ in the Rain,” which most people associate with the 1952 film musical of that name, is entering the public domain.

Fans of the Gene Kelly/Debbie Reynolds film may be unaware that it was conceived by Arthur Freed, then the head of MGM’s musical feature unit, as a vehicle to exploit the back catalog of songs he and composer Nacio Herb Brown had written in the 1920s and 1930s; of the 16 full-length and excerpted songs in the movie, all but two were original products of their collaboration or had words by Freed or music by Brown. “Moses Supposes” was written by others for the movie and “Make ‘Em Laugh,” by Freed and Brown, was acknowledged by Stanley Donen, who co-directed the firm with Kelly, to be a transparent rip-off of Cole Porter’s “Be a Clown.”

(My favorite backstage nugget about the movie’s production involves the physical torment that Reynolds, not a trained dancer, suffered at the hands of the perfectionist Kelly, which left her with bloodied feet after filming the “Good Morning” number. A close scrutiny of the scene reveals Reynolds continually glancing at the ground to make sure she was hitting her marks as she tried to keep in step with Kelly and co-star Donald O’Connor; anyway, no one can claim it doesn’t work perfectly.)

Sound recordings from 1924 are entering the public domain thanks to the 2018 Music Modernization Act. They include Gershwin’s recording of “Rhapsody in Blue” and Al Jolson’s recording of “California Here I Come.” But regular sound recordings made in 1929 are granted 100-year copyrights, so they won’t be available until 2030.

Another exception covers music made to accompany movies, which receive the same copyright terms as the films. Accordingly, Jenkins notes, the recorded version of “Singin’ in the Rain” heard in the film “The Hollywood Revue of 1929” goes royalty-free on Jan.1, but not the version sung by Kelly in the 1952 movie.

The annual flow of copyrighted works into the public domain underscores how the progressive lengthening of copyright protection is counter to the public interest—indeed, to the interests of creative artists. The initial U.S. copyright act, passed in 1790, provided for a term of 28 years including a 14-year renewal. In 1909, that was extended to 56 years including a 28-year renewal.

In 1976, the term was changed to the creator’s life plus 50 years. In 1998, Congress passed the Copyright Term Extension Act, which is known as the Sonny Bono Act after its chief promoter on Capitol Hill. That law extended the basic term to life plus 70 years; works for hire (in which a third party owns the rights to a creative work), pseudonymous and anonymous works were protected for 95 years from first publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter.

Along the way, Congress extended copyright protection from written works to movies, recordings, performances and ultimately to almost all works, both published and unpublished.

Once a work enters the public domain, Jenkins observes, “community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can perform the music publicly, without paying licensing fees. Online repositories such as the Internet Archive, HathiTrust, Google Books and the New York Public Library can make works fully available online. This helps enable both access to and preservation of cultural materials that might otherwise be lost to history.”

Indeed, as Jenkins and others have documented, overly long copyright terms often keep older works out of the mainstream. “Films have disintegrated because preservationists can’t digitize them,” Jenkins has written. “The works of historians and journalists are incomplete. Artists find their cultural heritage off-limits.”

The countervailing benefits are minimal. The artistic lobby — specifically corporate owners of copyrighted content — maintain that longer terms protect the income streams of content creators, producing an incentive to create. But the truth is that after the first few years of publication the commercial value of the vast majority of copyrighted works declines precipitously to almost nothing. The value that might arise from follow-on creations of public domain works remains locked away and the copyrighted works become forgotten.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThere’s a reason Metaphor: ReFantanzio’s battle music sounds as cool as it does

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoOn a quest for global domination, Chinese EV makers are upending Thailand's auto industry

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoNew Year life lessons from country star: 'Never forget where you came from'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24982514/Quest_3_dock.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24982514/Quest_3_dock.jpg) Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoMeta’s ‘software update issue’ has been breaking Quest headsets for weeks

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPassenger plane crashes in Kazakhstan: Emergencies ministry

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoIt's official: Biden signs new law, designates bald eagle as 'national bird'

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThese are the top 7 issues facing the struggling restaurant industry in 2025

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days ago'Politics is bad for business.' Why Disney's Bob Iger is trying to avoid hot buttons

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25814563/videoframe_30347.png)