Business

Opinion: Southern Californians shaped the nation's biggest political problems. We can solve them too

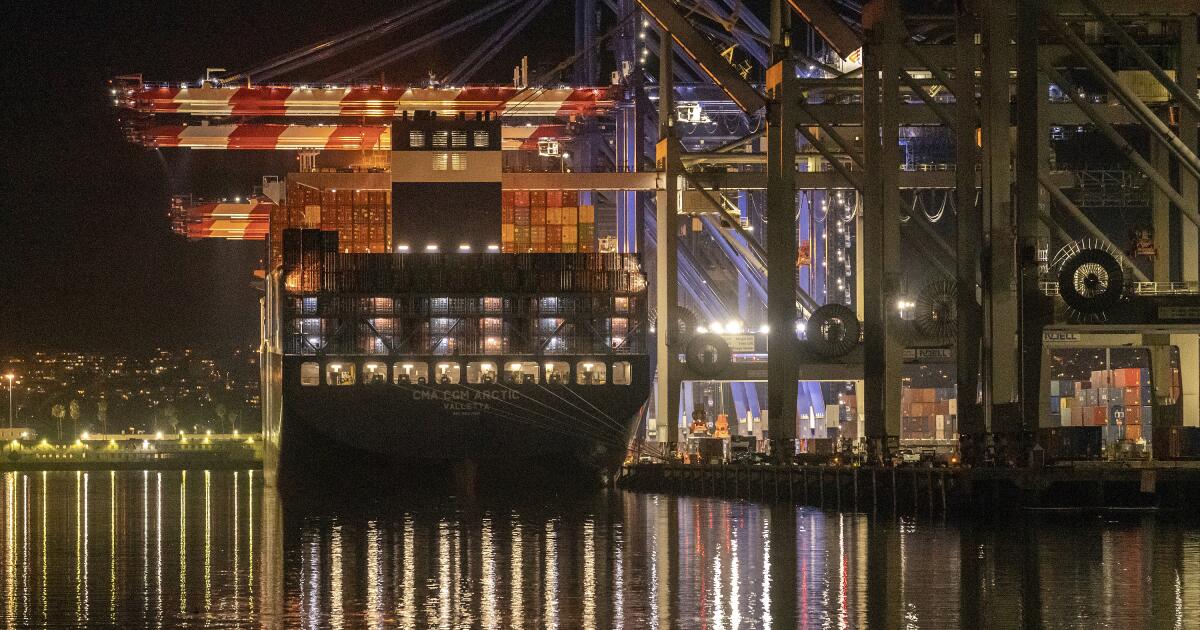

Voters rank the economy and inflation as the most important issues facing the country, and in spite of good news on both fronts, discontent over pocketbook issues remains steady. There’s one stretch of Southern California where, one could say, that all began: Los Angeles’ harbor and coast.

As the center for U.S. Pacific trade and an archetype for exuberant housing markets everywhere, the region’s waterfront clarifies why so many Americans feel frustrated and under pressure — and just how challenging it may be to fix this, no matter who becomes the next president.

Stretching back to the mid-19th century, when the United States annexed Southern California from the Mexican Republic, Americans looked to Pacific trade and westward settlement to stabilize their nation. That’s why our local ports were developed.

In the 1850s, a federal agency, then called the U.S. Coast Survey, identified San Pedro Bay as a focal point for shipping efforts. Since the 1910s, this has been home to the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach, collectively the busiest shipping hub in the Western Hemisphere, making the region prominent in global supply chains and transpacific trade.

Officials believed Pacific trade and settlement to be a safety valve for turmoil back East, that over slavery most of all. The results proved them wrong. Commerce and settlers intensified political conflict, both in Washington and in California, by increasing the stakes. Land speculators — in most places pushing out Indigenous people and Mexicans — looked to grab former rancho claims near California’s prospective harbors, in Southern California’s enviable climate. It was a rush for beachfront property like the region had never seen. Their actions set Los Angeles’ property lines and the basis for today’s real estate markets from Malibu to Newport Bay.

This history was invisible to me as I grew up around L.A., but its effects were and are all around, continuing to reshape Southern California during my lifetime. By the early 2000s, container ships, larger than before, accumulated in the outer waters as the ports were sometimes overwhelmed. Semitrucks crowded the 110 and 710 freeways. At the same time, the coastal real estate market boomed yet again. My parents — new arrivals to the region — found it full of opportunity. They purchased their first and only home, in a subdivision on former rancho lands, and they paid it off as valuations exploded around them and their nest egg grew. The region’s economy was a dynamo, a safe harbor in more ways than one.

Shipping and competitive real estate — two legacies of 1850s Southern California — remain with us. Moreover, they are part of an ongoing story of Los Angeles and its place in American life. Today’s voters’ sense of their economic well-being is based on the prices of household necessities, mostly imported goods, and about one-third enter the U.S. through the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Historically, the ships and containers that crowd San Pedro Bay have expanded affordability, but the COVID-19 pandemic and international crises disrupted their flow. Suddenly transpacific trade was blamed for soaring costs, not credited with making household items affordable. Even after the disruption abated, high prices and memories of scarcity have lingered. Nationally, politicians and the public have come to doubt the virtues of globalization. The clash between high hopes for Los Angeles’ harbors and the realities of global trade contribute once more to Americans’ sense of an uncertain world, and once again the high stakes linked to Southern California’s economy feed into tensions nationwide.

Sure investments, meanwhile, no longer offset troubled times. Americans’ primary investment — triumphant in the post-World War II era — is the single-family home. However, the nation’s high-priced real estate has unsettled this convention. Rather than absorbing newcomers and providing a path to financial security, it has multiplied voters’ sense of distress by locking many out of homeownership. The exhilarating prices and low interest rates of recent decades — profit and security to prior home purchasers — now put inflationary pressure on renters and prospective buyers, and on middle-income, low-income or young voters especially. This is most true around coastal Los Angeles, west and south of the 405 Freeway. It is true as well in markets farther afield, such as Phoenix and Las Vegas, long shaped by Southern California migrants and money.

The Southland’s residents and visitors were drawn to the promise of Pacific waters, just as generations before have been. And while many in all eras have benefited from the region’s industries and real estate appreciation, many others have always been left behind. Remembering such connections with history can clarify uncertain times. Recent polarization in U.S. politics has been compared to the Civil War era, but there is perhaps a more apt parallel between today and the 1860s: the economic ideas of trade and land investment, intended to calm political passions and to distribute prosperity, fell short in both moments.

The consequences will play out in the months ahead as pocketbook issues quite likely decide the presidential election. But regardless of the election’s outcome, we should understand that Southern California is never a place apart from U.S. politics and its dilemmas. Instead, these have deep roots in the region. And today, the region continues to invest in imports and real estate as vehicles for prosperity — even as the adverse costs accumulate in national politics.

That makes Southern California the opportune place to resolve these dilemmas of history and to lead the U.S. forward, whether by policy experimentation or new principles for how wealth might be built, sustained and shared. Shaping the nation’s better future will involve tough choices. It certainly will take visionaries and daring. Yet that, too, is a legacy of Southern California’s past, one ready to be reclaimed.

James Tejani, an associate professor of history at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, is the author of “A Machine to Move Ocean and Earth: The Making of the Port of Los Angeles and America.”

Business

The rise and fall of the Sprinkles empire that made cupcakes cool

After the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, Candace Nelson reevaluated her career. She had just been laid off from a boutique investment banking firm in San Francisco’s tech startup scene, and realized she wanted a change.

From her home, she launched a custom cake service that soon morphed into an idea for a cupcake-focused bakery. Nelson and her husband — whom she met at the Bay Area firm where she had worked — then pooled their savings, moved to Southern California and together opened Sprinkles Cupcakes from a 600-square-foot Beverly Hills storefront.

The store quickly sold out on opening day in 2005, and over the next two decades, the Sprinkles brand exploded across the country, opening dozens of locations of its specialty bakeries as well as mall kiosks and its signature around-the-clock cupcake ATMs in several states.

“It was an unproven concept and a big risk,” Nelson told the Times in 2013, at which point the business had 400 employees at 14 locations and dispensed upward of a thousand cupcakes a day from its Beverly Hills ATM alone.

But now, the iconic cupcake brand is no longer.

Sprinkles abruptly shut down all of its locations on Dec. 31, leaving hundreds of retail employees across Arizona; California; Washington, D.C.; Florida; Nevada; Texas; and Utah in a lurch with little notice, no severance and scrambling to fulfill a surge of orders from customers clamoring to get their last tastes.

Candace Nelson, the founder of Sprinkles cupcakes, in Beverly Hills in 2018.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Although Nelson long ago exited the company, having sold it to private equity firm KarpReilly LLC in 2012, she shared her disappointment with its fate on social media.

“As many of you know, I started Sprinkles in 2005 with a KitchenAid mixer and a big idea,” Nelson said in the post. “It’s surreal to see this chapter come to a close — and it’s not how I imagined the story would unfold.”

The company, now headquartered in Austin, Texas, made no formal announcement regarding the closures and Nelson has not said more than what she posted online. The company did share a comment with KTLA, saying “After thoughtful consideration, we’ve made the very difficult decision to transition away from operating company-owned Sprinkles bakeries.” Neither Nelson nor representatives of Sprinkles and KarpReilly responded to The Times’ requests for comment.

Sprinkles’ demise comes at a tough time for the food and beverage industry. At brick-and-mortar food retail locations, the non-negotiable ingredient and labor costs can be high. And shifting consumer sentiments away from sugar-filled sweets and toward more healthy and functional options, strained pocketbooks, as well as pushes by federal and state governments to nix artificial colors and flavoring, are creating uncertainties for businesses, those in the food industry said.

A 24-hour cupcake ATM at Sprinkles Cupcakes in Beverly Hills in 2012.

(Damian Dovarganes / Associated Press)

“Over the last 10 years the consumer has wizened up tremendously and is looking at the back of the label and choosing where to spend their sweets,” said David Jacobowitz, founder of Austin-based Nebula Snacks, an online food retailer.

At the same time, it’s also not uncommon for businesses owned by private-equity firms to close on a whim, where relentlessly profit-driven decisions might be made simply to pursue more lucrative projects. In recent years, private-equity deals have been seen to milk businesses for profit by slashing costs and quality, and have appeared to play a role in the breakup of some legacy retail brands, including Toys ‘R’ Us, Red Lobster, TGI Fridays and fabrics chain JoAnn Inc. On the flip side, private equity can help infuse much-needed cash into a business and extend its life.

Stevie León and her co-workers received a text the night before New Year’s Eve informing them the franchise Sprinkles location in Sarasota, Fla., where they worked would close permanently after their shifts the next day.

León, 33, said her position as a scratch baker mixing batter and frosting cupcakes overnight had been a dream job, since she had been searching for ways to develop baking skills without paying for expensive schooling.

“I really thought it was my forever job and it was taken away literally in a day,” she said. “I’m just taking it one day at a time.”

Ivy Hernandez, 27, the general manager at the Sarasota store, said that after the news was delivered to her boss, the franchise owner, they rushed to learn their options to keep the store afloat but quickly learned it could be legally precarious to continue operating. The store had been open less than a year.

A nearby corporate store, Hernandez said, had been in disarray for months, with employees contending with broken fridges and lapsed ingredient shipments, as managers implored higher-ups to pay the bills so the business could operate properly.

“It really felt like they were trying to do everything they could to screw everyone over as hard as possible until the end,” Hernandez said.

Sprinkles did not respond to questions about the franchise program or allegations of mismanagement in the lead-up to the closure.

A person walks by Sprinkles on the Upper East Side in New York City in 2020.

(Cindy Ord / Getty Images)

The obsession with tiny cakes in paper cups traces back to an episode of “Sex and the City” aired in 2000 showing Miranda and Carrie savoring cupcakes on a bench outside a West Village bakery called Magnolia’s Cupcakes.

“Big wasn’t a crush, he was a crash,” Carrie says to Miranda as she peels down the wrapper on a cupcake topped with bright pink buttercream frosting. She punctuates the quip by taking a big bite, leaving a glob of frosting on her face.

The scene sparked a tourism phenomenon for the bakery — which went on to create a “Carrie” line of cupcakes — and helped propel the burgeoning cupcake industry and companies like Sprinkles Cupcakes, Crumbs Bake Shop and Baked by Melissa to new heights.

Within a decade there was already talk of a “Cupcake Bubble,” coined by writer Daniel Gross in a 2009 Slate article where he argued that the 2008 economic recession laid the groundwork for a proliferation of cupcake stores across America, because a lot of people could figure out how to make tasty cupcakes cheaply and scale up without a huge capital investment.

Amid the decimation of many other local retail businesses, one could take over storefronts in heavily trafficked areas for cheap. As a result, “casual baking turned into an urban industry,” Gross said.

The cupcake fervor hit its peak when Crumbs, which had started as a single bakery on Manhattan’s Upper West Side in 2003, went public in a reverse merger worth $66 million in 2011. The wildly popular mini-cakes were selling at $4.50 a pop. But it became clear very quickly that it had grown too large, too fast. It closed in 2014 after it lost its stock listing on Nasdaq and defaulted on about $14.3 million in financing.

Analysts at the time said consumers were cooling on opulent desserts and suggested tougher times were ahead for bakeries that focused solely on cupcakes.

But Baked by Melissa has thus far proved those analysts wrong. The company has remained privately owned, and according to its founder, is focused on nationwide e-commerce operations — and on expanding the brand beyond sweets. Founder Melissa Ben-Ishay has gained a following on social media by sharing recipes for nutritious, easy-to-make meals.

“Businesses that prioritize quick value increases to get acquired often crash,” Ben-Ishay told Forbes last year. “We’re committed to maintaining product quality and steady, long-term growth.”

Before its unceremonious and sudden closure, Spinkles company leadership had pushed to diversify its business as part of a strategy to recover from a pandemic-era lull.

Chief Executive Dan Mesches told trade publication Nation’s Restaurant News in 2021 that comparable sales had grown since pre-pandemic years. He said the company had ramped up its direct-to-consumer and off-premises offerings and created a line of chocolates made to look like the tops of their cupcakes. The company also introduced a new franchise program with the goal of opening some 200 locations in the U.S. and abroad over three years.

“Innovation is everything for us,” Mesches said.

Sprinkles was known for, among other things, inventive and somewhat corny methods of customer delivery. Besides the trademark ATMs, the company’s vending machines found at many airports made loud, attention-drawing jingles, drawing dramatic complaints and jokes from TikTok travelers. In the 2010s, the company debuted a custom-built truck — “the Sprinklesmobile” — to deliver cupcakes to cities without physical locations.

Frances Hughes, co-founder of online wholesale marketplace Starch, said there’s no question that gourmet sweet treats are still in vogue. But brick-and-mortar locations are much more risky, with more unpredictability. Having large fixed costs makes a business “extremely sensitive to small changes in traffic or frequency,” while online or e-commerce models can be more flexible.

“I think cupcakes as a product still have demand. But the novelty paths that support that rapid retail expansion have passed,” Hughes said.

When Nelson, the Sprinkles founder, posted her somber message about the closure, she asked people to share memories of the company. Many offered heartfelt responses, her comments flooded with stories, for example, of poor college students making the trek to the Beverly Hills location for a limited number of first-come, first-served free cupcakes.

But many of the comments also criticized Nelson’s sale to private equity.

“You sold it to PE and expected it to not close?? What planet are you living on? I don’t begrudge you for selling as that’s entirely your choice but to think any PE firm cares about a company in the slightest is insanity,” one Instagram user said.

Nicole Rucker, an L.A.-based pastry chef and owner of Fat+Flour Pie Shop, said she didn’t observe a decline in the quality of the product after the private-equity takeover. She has been a longtime admirer of the company, driving up from San Diego to sample the cupcakes when its store opened. The simple attractiveness of the box and the logo, and the consistency in the way cupcakes were decorated, “was inspiring,” she said.

“It had a strong hold on people for years,” Rucker said.

Rucker said however that when a private-equity-owned business shutters, she doesn’t feel sadness: “I would rather give my money to a fellow small-business owner, because I would rather know that every dollar and every sale matters.”

Michelle Wainwright, the owner and founder of Indiana-based bakery Cute as a Cupcake! said that although the niche cupcake industry may no longer be in its heyday — with “Sex and the City” no longer airing and competitive baking show “Cupcake Wars” (which Candace Nelson served as a judge on) now canceled — they are still versatile treats, with great potential for creativity.

And they are sentimental to her, because she uses her grandmother’s recipe.

“Cupcakes are still a winner,” Wainwright said. “It’s my belief that a life with out cupcakes is a life without love.”

Business

Bay Area semiconductor testing company to lay off more than 200 workers

Semiconductor testing equipment company FormFactor is laying off more than 200 workers and closing manufacturing facilities as it seeks to cut costs after being hit by higher import taxes.

The Livermore, Calif.,-based company plans to shutter its Baldwin Park facility and cut 113 jobs there on Jan. 30, according to a layoff notice sent to the California Employment Development Department this week. Its facility in Carlsbad is scheduled to close in mid-December later this year, which will result in 107 job losses, according to an earlier notice.

Technicians, engineers, managers, assemblers and other workers are among those expected to lose their jobs, according to the notices.

The company offers semiconductor testing equipment, including probe cards, and other products. The industry has been benefiting from increased AI chip adoption and infrastructure spending.

FormFactor is among the employers that have been shedding workers amid more economic uncertainty.

Companies have cited various reasons for workforce reductions, including restructuring, closures, tariffs, market conditions and artificial intelligence, which can help automate repetitive tasks or generate text, images and code.

The tech industry — a key part of California’s economy — has been hit hard by job losses after the pandemic, which spurred more hiring, and amid the rise of AI tools that are reshaping its workforce.

As tech companies and startups compete fiercely to dominate the AI race, they’ve also cut middle management and other workers as they move faster to release more AI-powered products. They’re also investing billions of dollars into data centers that house computing equipment used to process the massive troves of information needed to train and maintain AI systems.

Companies such as chipmaker Nvidia and ChatGPT maker OpenAI have benefited from the AI boom, while legacy tech companies such as Intel are fighting to keep up.

FormFactor’s cuts are part of restructuring plans that “are intended to better align cost structure and support gross margin improvement to the Company’s target financial model,” the company said in a filing to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission this week.

The company plans to consolidate its facilities in Baldwin Park and Carlsbad, the filing said.

FormFactor didn’t respond to a request for comment.

FormFactor has been impacted by tariffs and seen its growth slow. The company employs more than 2,000 people and has been aiming to improve its profit margins.

In October, the company reported $202.7 million in third-quarter revenue, down 2.5% from the third quarter of fiscal 2024. The company’s net income was $15.7 million in the third quarter of 2025, down from $18.7 million in the same quarter of the previous year.

FormFactor’s stock has been up 16% since January, surpassing more than $67 per share on Friday.

Business

In-N-Out Burger outlets in Southern California hit by counterfeit bill scam

Two people allegedly used $100 counterfeit bills at dozens of In-N-Out Burger restaurants in Southern California in a wide-reaching scam.

Glendale Police officials said in a statement Friday that 26-year-old Tatiyanna Foster of Long Beach was taken into custody last month. Another suspect, 24-year-old Auriona Lewis, also of Long Beach, was arrested in October.

Police released images of $100 bills used to purchase a $2.53 order of fries and a $5.93 order of a Flying Dutchman.

The Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office charged Lewis with felony counterfeiting and grand theft in November.

Elizabeth Megan Lashley-Haynes, Lewis’s public defender, didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Glendale police said that Lewis was arrested in Palmdale in an operation involving the U.S. Marshals Task Force. Foster is expected in court later this month, officials said.

”Lewis was found to be in possession of counterfeit bills matching those used in the Glendale incident, along with numerous gift cards and transaction receipts believed to be connected to similar fraudulent activity,” according to a police statement.

A representative for In-N-Out Burger told KTLA-TV that restaurants in Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego counties were also targeted by the alleged scam.

“Their dedication and expertise resulted in the identification and apprehension of the suspects, helping to protect our business and our communities,” In-N-Out’s Chief Operations Officer Denny Warnick said. “We greatly value the support of law enforcement and appreciate the vital role they play in making our communities stronger and safer places to live.”

The company, opened in 1948 in Baldwin Park, has restaurants in nine states.

An Oakland location closed in 2024, with the owner blaming crime and slow police response times.

Company chief executive Lynsi Snyder announced last year that she planned to relocate her family to Tennessee, although the burger chain’s headquarters will remain in California.

-

Detroit, MI1 week ago

Detroit, MI1 week ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX3 days ago

Dallas, TX3 days agoAnti-ICE protest outside Dallas City Hall follows deadly shooting in Minneapolis

-

Dallas, TX6 days ago

Dallas, TX6 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Delaware2 days ago

Delaware2 days agoMERR responds to dead humpback whale washed up near Bethany Beach

-

Iowa5 days ago

Iowa5 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Nebraska4 days ago

Nebraska4 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska