Colorado

Grief lingers 5 years after COVID-19 arrived in Colorado, killing thousands

PUEBLO — When paramedics showed up at Bernie Esquibel-Tennant’s door the day after Thanksgiving in 2020, it was the second time in roughly 12 hours that an ambulance had visited her stretch of the neighborhood.

The night before, Esquibel-Tennant had watched as paramedics came for Adolph Gallardo, a man her children called Grandpa who lived across the street. Now they were here for her sister Melissa.

Melissa Esquibel’s oxygen level had dropped dangerously low to 70% overnight, which is why Esquibel-Tennant called 911 and paramedics were at her door even before the sun rose that Friday morning in Pueblo.

But the paramedics wouldn’t come in — not with COVID-19 in the house. So Esquibel-Tennant helped Melissa, dressed only in a nightgown, outside. They were barefoot and the ground was cold.

“We love you,” Esquibel-Tennant, 54, recalled telling Melissa as she helped her onto the waiting gurney.

She never saw her sister again after the paramedics drove away on Nov. 27, 2020. Adolph, their 77-year-old neighbor, never returned home, either.

He and Melissa, 47, are among the nearly 16,000 Coloradans who have died due to COVID-19 since the pandemic began five years ago this month. And their families are among the thousands still grieving, still wondering how the virus made its way into their homes and still struggling with how their loved ones died alone during the early days of the pandemic.

“There just weren’t a lot of procedures in place,” Esquibel-Tennant said. “Then, emotionally, we weren’t ready to deal with it.”

Closure — if such a thing exists — is still out of reach for many pandemic survivors. Their grief is complicated by unknowns and what-ifs. Rituals they historically used to mourn and honor the dead were postponed or scrapped entirely during the height of the pandemic.

And yet the world has seemingly moved on even as so many still grieve and COVID-19 remains, though we now have vaccines and better treatment. There’s no state memorial honoring the thousands who have died in the worst public health crisis of a century. There’s no finality as hundreds still die from the virus each year in Colorado.

“Over 15,000 Coloradans died due to COVID,” Gov. Jared Polis said in a recent interview, noting he lost two friends to the virus. “Some would have perhaps passed away by now anyway. Others would be perfectly healthy other than that COVID felled them. There’s no getting those people back.”

Misinformation and conspiracies spread during the pandemic, leading a swath of the American population to dismiss the severity of the disease that has killed more than 1 million people nationwide. At the same time, the death toll hasn’t fallen equitably as Black and Latino Coloradans died at disproportionately high rates compared to their white peers.

“I hope people know now how bad COVID was,” Adolph’s widow Ernestine “Toni” Gallardo said, adding, “We’ve experienced a real, real pandemic.”

Colorado’s first death

Ski season was well underway in the high country when the virus was first confirmed in Colorado on March 5, 2020.

At the time, COVID-19 already had been discovered in California, Florida and Washington state, although the virus is now believed to have been slinking its way across the United States well before then undetected.

In Colorado, the number of confirmed cases, mostly clustered in mountain towns crowded with tourists, ticked up in the days that followed. Health officials first confirmed a Coloradan had died from COVID-19 on March 13, 2020.

Dr. Leon Kelly, at the time El Paso County’s elected coroner, was standing on a stage with Polis and other state officials for a news conference about that first COVID-19 fatality — a woman in her 80s — when he got a phone call.

Employees from El Paso County’s health department were trying to reach Kelly, who had just also been appointed the county’s deputy medical director.

There was a problem, they told him.

The woman who died had attended a bridge tournament in Colorado Springs two weeks earlier and scores of people — most of them elderly — were potentially exposed to the virus.

Hearing the news was like being in a movie, Kelly said, when you find out the “absolute worst-case scenario has occurred.”

Public health employees spent the weekend tracking down attendees. Meanwhile, Kelly called an aunt in North Carolina who played bridge. They didn’t talk frequently, but Kelly wanted her to explain how the game worked, what happened with the cards and whether players rotated between tables during a tournament.

Kelly quickly realized that as many as 150 people were potentially exposed to the virus at that single event.

“It was clear we were already behind the ball,” Kelly recalled.

At least four attendees of that bridge tournament died from COVID-19.

The virus killed thousands more Coloradans in the months and years that followed, including Adolph Gallardo and Melissa Esquibel.

“We thought we were good”

Melissa, born March 19, 1973, was the youngest of three siblings. She was small in stature and — having been diagnosed with Turner syndrome when she was 9 — looked like she was about 12 years old.

Melissa had other disabilities, such as being hard of hearing, but she was very social and worked for Furr’s Cafeteria for decades, then McDonald’s until the virus sent everyone home.

She was “spunky,” her sister Bernie Esquibel-Tennant said.

The family was unable to visit Melissa in the hospital because they were also sick with COVID-19. Doctors and nurses kept Esquibel-Tennant updated on her sister through phone calls. They told her when Melissa ate scrambled eggs — and when Melissa went into cardiac arrest.

“They were overwhelmed with the amount of care everyone needed,” Esquibel-Tennant recalled.

At that point in November 2020, Colorado was in the middle of one of the state’s deadliest waves of COVID-19. So many people were sick that efforts by state and local public health departments to test and track the virus faltered.

The governor had warned hospitals of the influx of patients they were about to receive just two weeks before paramedics came for Melissa Esquibel and Adolph Gallardo.

Soon hospitals across the state were inundated. Mesa County ran out of intensive-care beds. Weld County only had three ICU beds at one point. Metro Denver hospitals turned away ambulances.

Parkview Medical Center in Pueblo canceled inpatient surgeries and sent patients to Colorado Springs and Denver. Staff also asked the county coroner to take bodies if more people died than could be stored in the hospital’s morgue.

Pueblo had one of the highest COVID-19 death rates in the state by mid-December and the coroner was using a semitrailer to store extra bodies.

Esquibel-Tennant’s family had tried to minimize their exposure to the virus, but she worked in social services and could not always do so remotely.

By then the virus was so rampant throughout the community there was no way to know who brought COVID-19 into the house, much less where they got it from — including whether mixing between the Gallardo and Esquibel-Tennant families spread the virus between them.

“We thought we were good,” Ernestine Gallardo, 78, said. “We weren’t associating with a lot of people.”

She and Adolph met when they were children. He lived in Florence, but would visit his aunt in Pueblo. Adolph served in the U.S. Marine Corps, including two tours in Vietnam, and received the Purple Heart for his service.

He and Esquibel-Tennant’s husband were “two peas in a pod,” Ernestine Gallardo said.

In mid-November, around the same time the Esquibel-Tennant household got sick, Adolph caught what he initially thought was a cold. He was prone to colds and got them each winter, Ernestine Gallardo said.

It was COVID-19. Adolph spent his final Thanksgiving mostly in bed struggling to breathe before paramedics came that evening.

Melissa Esquibel went into cardiac arrest at Parkview Medical Center three days later.

Medical staff tried to resuscitate her, but Melissa had little to no heartbeat. Her bones were fragile because of Turner syndrome and doctors told Esquibel-Tennant that their attempts to save her sister had crushed Melissa’s body.

“I felt the hurt in the doctor,” Esquibel-Tennant said.

She asked the physician to have hospital staff call her when Melissa died. Hours passed and Esquibel-Tennant still hadn’t received a call, so she dialed the hospital herself. A staff member paused before telling her they had forgotten to call.

Melissa had already died.

“She probably just died by herself,” Esquibel Tennant said. “Nobody to comfort her.”

Melissa passed away on Nov. 29, 2020.

Nearly five years later, questions still linger in Esquibel-Tennant’s mind, mainly about the quality of care her sister received and whether Melissa died the way she was told.

“I can’t blame anybody,” she said. “…But because there were so many great unknowns you just had to trust what you were being informed about.”

“We’re stuck” in grief

A pandemic plan drafted by Colorado’s public health department in 2018 found that if there was a major health crisis, “there may be a need for public mourning, psychological support and a slow transition into a new normal.”

But since the pandemic, more people are feeling isolated and overwhelmed as they grieve, said Micki Burns, head of Judi’s House, an organization that helps grieving families.

“We’re stuck (in grief) because the pandemic divided us in such distinct ways,” she said. “Until we are able to heal and reunite and connect we’re probably going to remain stuck.”

A group called Marked by COVID is advocating for a national memorial in Washington, D.C. so that society can pause and remember “this unprecedented loss of life that we have experienced,” said Kristin Urquiza, co-founder and executive director.

But for now, many Coloradans grieve alone.

Ca-Sandra Goodrich, who lives in Aurora, was unable to attend the funeral held for her cousin Necole Dandridge, who died from COVID-19 at age 39 on Nov. 9, 2021.

Instead, Goodrich watched the funeral via a livestream because she herself was sick with the virus.

“I remember feeling left out,” Goodrich, 53, said.

When Goodrich thinks about the pandemic, she remembers all that her family has lost. Her extended family is large and more than a dozen members have passed away in the years since the virus first swept the state.

Only Necole’s death was attributed to COVID-19, but Goodrich can’t help but to wonder whether other relatives who had respiratory symptoms at the time they died might have also had the virus.

“It’s just in the shadows,” Goodrich said. “…It’s almost like COVID is the phantom or the ghost that no one is acknowledging. “

The loss changed Goodrich, who struggles with her own health.

“I’m reluctant to get close to an individual,” she said.

Misinformation swirled around COVID-19 deaths

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment had prepared for the possibility of a pandemic years earlier by running simulations with local health departments. But there was a major aspect of COVID-19 that public health officials hadn’t known to prepare for: misinformation and conspiracy theories.

“That was a new dynamic and the level of misinformation — it was challenging to counteract that,” said Jill Hunsaker Ryan, the state’s public health director. “If public health says, ‘We recommend you wear a mask’ — we would have thought that that’s something that would have been accepted universally. But it wasn’t.”

Among the things that became politically divisive during the pandemic was how state and federal health departments counted and publicly reported COVID-19 deaths.

Officials said from the beginning of the crisis that the number of people who died from the virus was likely undercounted because of delays in testing. But critics claimed the death toll was inflated.

The debate came to a head in May 2020 when a state lawmaker alleged the Department of Public Health and Environment falsified the number of people who died from the virus and called for criminal charges to be filed against Hunsaker Ryan.

“I regarded it as a conspiracy theory and still do,” said Ian Dickson, who worked as a communications specialist with the state health department in 2020. “We also weren’t doing anything to get ahead of it.”

The agency denied altering death certificates, but responded by changing how Colorado publicly reported COVID-19 deaths. The decision, Dickson said, “really lent credence to a conspiracy theory.”

“From a communications standpoint it was a mess,” he said.

The department in May 2020 split deaths into two categories: those who died from the virus and those who had COVID-19 when they died, but it was not the leading cause.

“My directive was just get the best data, be transparent,” Polis recalled in an interview.

There was often a narrow gap between the two figures during the height of the pandemic, but the number of people who died from the virus was typically lower than those who died with COVID-19 because it only included fatalities listed on death certificates as being caused directly by the disease.

Yet medical professionals use what they call the “but for” principle when determining a cause of death, which says: if “but for (a certain event),” a person would not have died at this specific time and place. So deaths are ruled COVID-19 fatalities when the virus causes a person to die by triggering a condition that leads to their death, such as heart attacks, strokes or septic shock.

“If in those early weeks of the pandemic, we had relied exclusively on that final death certificate coded data, it would have been weeks, maybe even months until we had counts,” state epidemiologist Dr. Rachel Herlihy said. “That would have misled the public.”

“We were really at a very difficult time trying our best to get information to the public as quickly as we could,” she added.

The spread of misinformation affected Coloradans who lost loved ones to the virus.

There were many times during the height of the pandemic when families didn’t want COVID-19 to be listed on their relatives’ death certificates, said Kelly, the former El Paso County coroner. A person even screamed at Kelly over the phone, he said, telling him that COVID-19 wasn’t real and that he wouldn’t accept the virus as his father’s cause of death.

“These people were being lied to and they were being manipulated in many ways,” Kelly said.

Kelly, in his dual roles during the pandemic, performed autopsies in the morning on people who died from the virus and then spent his afternoons trying to prevent those deaths with El Paso County’s health department.

For almost a year, Kelly collected death certificates and reviewed them for accuracy because there were so many questions about how people died. The notebook with those death certificates sat on his desk for nearly five years until he shredded them earlier this year after he stepped down as coroner.

“I took it so personal. It was my responsibility to keep people safe,” he said. “…I had failed.”

“It just leaves a hole in your heart”

Ernestine Gallardo doesn’t like to think about Thanksgiving anymore, much less cook a traditional feast of turkey, stuffing or mashed potatoes.

Adolph’s pet peeve was lumpy potatoes.

But he’s not here anymore and Thanksgiving has never been the same. The family opted out of the holiday two years ago, choosing to dine at a Chinese restaurant instead.

“It’s too hard for me to think of doing things that he really enjoyed,” Ernestine Gallardo said.

Ernestine Gallardo and her daughter, Angela, were able to be with Adolph when he died on Dec. 10, 2020.

But the patriarch’s other children, Patrick and Pamela Gallardo, weren’t there because they were sick.

“That still haunts me,” Patrick Gallardo, 58, said.

Angela Gallardo, 54, wonders sometimes if it would have been better if she hadn’t gone to the hospital.

“I feel selfish because I was able to be there with my dad and hold his hand and rub his arm,” she said.

The Gallardos lost a second family member to COVID-19 nine months later. Pamela Gallardo’s son, Andrew Valdez, had the virus earlier in the pandemic and died of a heart attack in his sleep on Sept. 26, 2021. He was 31.

“We couldn’t be with them at all and then for them to pass by themselves — it just leaves a hole in your heart that’s never gonna fill back up no matter what you do,” Pamela Gallardo 54, said.

“There’s still no closure”

Esquibel-Tennant went to Parkview Medical Center to pick up her sister’s belongings in December 2020, a couple weeks after Melissa died.

When she opened the bag given to her by staff, Esquibel-Tennant saw only a nightgown — the one her sister had worn when the paramedics came.

“How horrible,” Esquibel thought. “That’s all I have left of my sister.”

Melissa was cremated, a first for their family. Esquibel-Tennant hadn’t wanted her sister’s body to sit in a morgue or freezer truck.

But it meant she never saw Melissa’s body or what she looked like when she died. She still wonders what happened in her sister’s final moments.

On the way home from the hospital, Esquibel-Tennant stopped at a car wash and tossed her sister’s nightgown in a trash bin.

“There’s still no closure,” she said.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get health news sent straight to your inbox.

Colorado

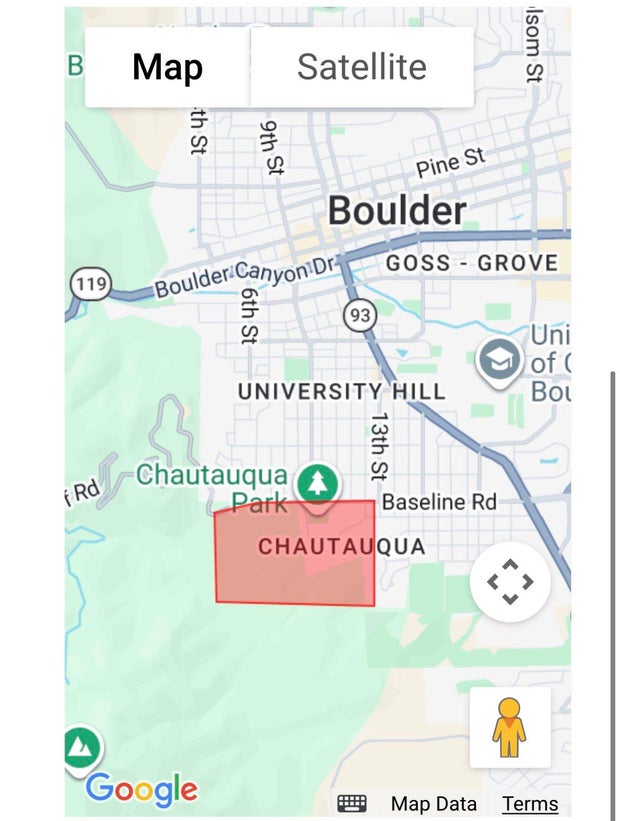

Evacuation warning issued for area near wildfire in southwest Boulder

Authorities have issued an evacuation warning for homes near a wildfire that broke out in southwest Boulder on Saturday afternoon.

Just before 1 p.m., Boulder Fire Rescue said a wildfire sparked in the southwest part of Boulder’s Chautauqua neighborhood. The Bluebell Fire is currently estimated to be approximately five acres in size, and more than 50 firefighters are working to bring it under control. Mountain View Fire Rescue is assisting Boulder firefighters with the operation.

Around 1:30, emergency officials issued an evacuation warning to the residents in the area of Chatauqua Cottages. Residents in the area should be prepared in case they need to evacuate suddenly.

Officials have ordered the DFPC Multi-Mission Aircraft (MMA) and Type 1 helicopter to assist in firefighting efforts. Boulder Fire Rescue said the fire has a moderate rate of spread and no containment update is available at this time.

Red Flag warnings remain in place for much of the Front Range as windy and dry conditions persist.

Colorado

Two-alarm fire damages hotel in Estes Park, 1 person taken to a Colorado hospital

A two-alarm fire damaged a hotel in Estes Park on Friday night. It happened at Expedition Lodge Estes Park just north of Lake Estes.

The lodge, located at 1701 North Lake Avenue on the east side of the Colorado mountain town, was evacuated after 8:30 p.m. and the fire chief said by 10 p.m. the fire was under control.

One person was hurt and taken to a hospital.

The cause of the fire is under investigation. So far it’s not clear how much damage it caused.

A total of 25 firefighters fought the blaze.

Colorado

Warm storm delivers modest totals to Colorado’s northern mountains

Lucas Herbert/Arapahoe Basin Ski Area

Friday morning wrapped up a warm storm across Colorado’s northern and central mountains, bringing totals of up to 10 inches of snowfall for several resorts.

Higher elevation areas of the northern mountains — particularly those in and near Summit County and closer to the Continental Divide — received the most amount of snow, with Copper, Winter Park and Breckenridge mountains seeing among the highest totals.

Meanwhile, lower base areas and valleys received rain and cloudy skies, thanks to a warmer storm with a snow line of roughly 9,000 feet.

Earlier this week, OpenSnow meteorologists predicted the storm’s snow totals would be around 5-10 inches, closely matching actual totals for the northern mountains. The central mountains all saw less than 5 inches of snow.

Here’s how much snow fell between Wednesday through Friday morning for some Western Slope mountains, according to a Friday report from OpenSnow:

Aspen Mountain: 0.5 inches

Snowmass: 0.5 inches

Copper Mountain: 10 inches

Winter Park: 9 inches

Breckenridge Ski Resort: 9 inches

Arapahoe Basin Ski Area: 8.5 inches

Keystone Resort: 8 inches

Loveland Ski Area: 7 inches

Vail Mountain: 7 inches

Steamboat Resort: 6 inches

Beaver Creek: 6 inches

Irwin: 4.5 inches

Cooper Mountain: 4 inches

Sunlight: 0.5 inches

Friday and Saturday will be dry, while Sunday will bring northern showers. The next storms are forecast to be around March 3-4 and March 6-7, both favoring the northern mountains.

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana6 days ago

Louisiana6 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO3 days ago

Denver, CO3 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT