California

Why California Still Doesn’t Mandate Dyslexia Screening

This article was originally published in CalMatters.

California sends mixed messages when it comes to serving dyslexic students.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom is the most famous dyslexic political official in the country, even authoring a children’s book to raise awareness about the learning disability. And yet, California is one of 10 states that doesn’t require dyslexia screening for all children.

Education experts agree that early screening and intervention is critical for making sure students can read at grade level. But so far, state officials have done almost everything to combat dyslexia except mandate assessments for all students.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

“It needs to happen,” said Lillian Duran, an education professor at the University of Oregon who has helped develop screening tools for dyslexia. “It seems so basic to me.”

Since 2015, legislators have funded dyslexia research, teacher training and the hiring of literacy coaches across California. But lawmakers failed to mandate universal dyslexia screening, running smack into opposition from the California Teachers Association.

The union argued that since teachers would do the screening, a universal mandate would take time away from the classroom. It also said universal screening may overly identify English learners, mistakenly placing them in special education.

The California Teachers Association did not respond to requests for comment for this story. In a letter of opposition to a bill in 2021, the union wrote that the bill “is unnecessary, leads to over identifying dyslexia in young students, mandates more testing, and jeopardizes the limited instructional time for students.”

In response, dyslexia experts double down on well-established research. Early detection actually prevents English learners — and really, all students — from ending up in special education when they don’t belong there.

While California lawmakers didn’t vote to buck the teachers union, they haven’t been afraid to spend taxpayer money on dyslexia screening. In the past two years, the state budget allocated $30 million to UC San Francisco’s Dyslexia Center, largely for the development of a new screening tool. Newsom began championing the center and served as its honorary chair in 2016 when he was still lieutenant governor.

“There’s an inadequate involvement of the health system in the way we support children with learning disabilities,” said Maria Luisa Gorno-Tempini, co-director of UCSF’s Dyslexia Center. “This is one of the first attempts at bridging science and education in a way that’s open sourced and open to all fields.”

Parents and advocates say funding dyslexia research and developing a new screener can all be good things, but without mandated universal screening more students will fall through the cracks and need more help with reading as they get older.

Omar Rodriguez, a spokesperson for the governor did not respond to questions about whether Newsom would support a mandate for universal screening. Instead, he listed more than $300 million in state investments made in the past two years to fund more reading coaches, new teacher credentialing requirements and teacher training.

The screening struggle

Rachel Levy, a Bay Area parent, fought for three years to get her son Dominic screened for dyslexia. He finally got the screening in third grade, which experts say could be too late to prevent long-term struggles with reading.

“We know how to screen students. We know how to get early intervention,” Levy said. “This to me is a solvable issue.”

Levy’s son Dominic, 16, still remembers what it felt like trying to read in first grade.

“It was like I was trying to memorize the shape of the word,” he said. “Even if I could read all the words, I just wouldn’t understand them.”

Dyslexia is a neurological condition that can make it hard for students to read and process information. But teachers can mitigate and even prevent the illiteracy stemming from dyslexia if they catch the signs early.

Levy, who also has dyslexia, said there’s much more research today on dyslexia than there was 30 years ago when she was first diagnosed. She said she was disappointed to find that California’s policies don’t align with the research around early screening.

“Unfortunately, most kids who are dyslexic end up in the special education system,” Levy said. “It’s because of a lack of screening.”

Soon after his screening in third grade, Dominic started receiving extra help for his dyslexia. He still works with an educational therapist on his reading, and he’s just about caught up to grade level in math. The biggest misconception about dyslexia, Dominic said, is that it makes you less intelligent or capable.

“Dyslexics are just as smart as other people,” he said. “They just learn in different ways.”

The first step to helping them learn is screening them in kindergarten or first grade.

“The goal is to find risk factors early,” said Elsa Cárdenas-Hagan, a speech-language pathologist and a professor at the University of Houston. “When you find them, the data you collect can really inform instruction.”

Cárdenas-Hagan’s home state of Texas passed a law in 1995 requiring universal screening. But she said it took several more years for teachers to be trained to use the tool. Her word of caution to California: Make sure teachers are not only comfortable with the tool but know how to use the results of the assessment to shape the way they teach individual students.

A homegrown screener

UC San Francisco’s screener, called Multitudes, will be available in English, Spanish and Mandarin. It’ll be free for all school districts.

Multitudes won’t be released to all districts at once. UCSF scientists launched a pilot at a dozen school districts last year, and they plan to expand to more districts this fall.

But experts and advocates say there’s no need to wait for it to mandate universal screenings. Educators can use a variety of already available screening tools in California, like they do in 40 other states. Texas and other states that have high percentages of English learners have Spanish screeners for dyslexia.

For English learners, the need for screening is especially urgent. Maria Ortiz is a Los Angeles parent of a dyslexic teenager who was also an English learner. She said she had to sue the Los Angeles Unified School District twice: once in 2016 to get extra help for her dyslexic daughter when she was in fourth grade and again in 2018 when those services were taken away. Ortiz said the district stopped giving her daughter additional help because her reading started improving.

“In the beginning they told me that my daughter was exaggerating,” Ortiz said.

“They said everything would be normal later.”

California currently serves about 1.1 million English learners, just under a fifth of all public school students. For English learners, dyslexia can be confused with a lack of English proficiency. Opponents of universal screening, including the teachers association, argue that English learners will be misidentified as dyslexic simply because they can’t understand the language.

“Even the specialists were afraid that the problem might be because of the language barrier,” Ortiz said about her daughter’s case.

But experts say dyslexia presents a double threat to English learners: It stalls them from reading in their native language and impedes their ability to learn English. And while there are some Spanish-language screeners, experts from Texas and California say there’s room for improvement. Current Spanish screeners penalize students who mix Spanish and English, they say.

Duran, who helped develop the Spanish version of Multitudes, said the new screener will be a better fit for how young bilingual students actually talk.

“Spanglish becomes its own communication that’s just as legitimate as Spanish on its own or English on its own,” Duran said. “It’s about the totality of languages a child might bring.”

Providing Multitudes free of cost is important to schools with large numbers of low-income students. Dyslexia screeners cost about $10 per student, so $30 million might actually be cost-effective considering California currently serves 1.3 million students in kindergarten through second grade. The tool could pay for itself in a few years. Although there are plenty of screeners already available, they can stretch the budgets of high-poverty schools and districts.

“The least funded schools can’t access them because of the cost,” Duran said.

In addition to the governor, another powerful state lawmaker, Glendale Democratic state Sen. Anthony Portantino, is dyslexic. While chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, he has repeatedly, and unsuccessfully, authored legislation to require public schools to screen all students between kindergarten and second grade.

Portantino’s 2021 bill received unanimous support in the Senate Education and Appropriations committees, but the bill died in the Assembly Education Committee. Portantino authored the same bill in 2020, but it never made it out of the state Senate.

“We should be leading the nation and not lagging behind,” Portantino said.

Portantino blamed the failure of his most recent bill on former Democratic Assemblymember Patrick O’Donnell, who chaired the Assembly Education Committee, for refusing to hear the bill.

“It’s no secret, Patrick O’Donnell was against teacher training,” Portantino said. “He thought our school districts and our educators didn’t have the capacity.”

O’Donnell did not respond to requests for comment. Since O’Donnell didn’t schedule a hearing on the bill, there is no record of him commenting about it at the time.

Portantino plans to author a nearly identical bill this year. He said he’s more hopeful because the Assembly Education Committee is now under the leadership of Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi, a Democrat from Torrance. Muratsuchi would not comment on the potential fate of a dyslexia screening bill this year.

Levy now works as a professional advocate for parents of students with disabilities. She said without mandatory dyslexia screening, only parents who can afford to hire someone like her will be able to get the services they need for their children.

“A lot of high school kids are reading below third-grade level,” she said. “To me, that’s just heartbreaking.”

This was originally published on CalMatters.

California

California coffee growing pioneers die of unknown causes, leaving behind 3 children

Authorities are investigating the sudden deaths of a Central Coast couple who pioneered California’s coffee-growing movement from their Santa Barbara County farm.

Jay and Kristen Ruskey, owners of Good Land Organics and co-founders of Frinj Coffee, died Sunday at a home in Cambria, the San Luis Obispo County Sheriff’s Department confirmed Friday.

Authorities have not released how the couple died. Autopsies were performed Thursday and toxicology results are expected in a few weeks, said Tony Cipolla, public information officer for the Sheriff’s Department.

“At this time, the deaths do not appear to be suspicious,” Cipolla said.

A GoFundMe created to support the Ruskey family members with funeral costs, memorial arrangements and other expenses had raised more than $133,000 as of Friday afternoon. The couple has three children: Kasurina, 19, Sean, 16 and Aiden, 16, according to the fundraiser.

The Ruskeys helped develop more than 65 coffee farms from Santa Barbara to north of San Diego that grow 14 varieties of coffee. Jay Ruskey was lauded as the first farmer to sell locally grown coffee in California.

Jay Ruskey established Good Land Organics in the early 1990s, growing exotic fruit at a farm in Goleta. The couple launched their coffee brand, Frinj, in 2017.

The couple’s coffee venture took off after Jay Ruskey tried several times to plant coffee trees in 2002 with a goal of learning the best practices for growing coffee in Southern California.

“I have always been passionate about crop adaptation,” Ruskey told The Times in 2024. “I was working with the UC Cooperative Extension Service to plant lychee and longans when Dr. Mark Gaskell, a small berry crop expert, gave me 40 coffee plants and encouraged me to try planting them side by side with other plants.”

In 2024, Frinj Coffee filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, claiming about $215,000 in assets while listing more than $1.8 million in liabilities, the Santa Barbara Independent reported. The company regained its footing at the start of the year and, in January, it was the first California-based coffee grower to ever compete in the Dubai Coffee Auction.

California

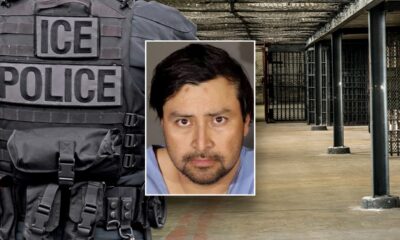

California man sentenced to 10 years for drug trafficking in Baltimore

A California man was sentenced to 10 years in prison for his role in a drug trafficking group that operated in Baltimore, according to the Maryland State’s Attorney’s Office.

In 2023, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) began investigating a group in Baltimore that was selling large amounts of cocaine, according to court documents.

Investigators determined that Mario Valencia-Birruetta, 35, of Corning, California, was a member of the group. He was placed on a flight watch list, court records show.

Drug trafficking investigation

In August 2023, a commercial airline notified investigators that Valencia-Birruetta was flying to Baltimore. On Aug. 15, 2023, investigators began tracking his movements as he stayed at a Hamilton Residence hotel in Baltimore, according to court records.

Between Aug. 15 and Aug. 24, investigators watched as Valencia-Birruetta met with multiple drug traffickers. According to court documents, they arrived at the hotel with bags.

In one case, investigators saw Valencia-Birruetta carrying large amounts of money in his hand. He went to the bank and appeared to make a deposit, court documents show.

On Aug. 24, 2023, Valencia-Birruetta left Baltimore. A week later, investigators were notified that he planned to travel back to Baltimore, according to court documents.

On Aug. 30, 2023, investigators watched as Valencia-Birruetta arrived at BWI Airport, picked up a rental car and drove to the Hamilton Residence hotel, court documents show.

At the same time, another group of investigators was surveilling a stash house in Baltimore County where co-conspirators were seen carrying bags into the location.

Investigators learned that a co-conspirator had picked up Valencia-Birruetta from the hotel and traveled to National Harbor, Maryland, where they met another co-conspirator. After the meeting, Valencia-Birruetta and the co-conspirator drove back to the stash house, court documents show.

When Valencia-Birruetta and the co-conspirator got out of the vehicle and removed duffel bags, investigators approached and saw that one of the bags had a large hole.

According to court documents, the investigators were able to see kilogram packages of drugs in the bag.

Officials detained Valencia-Birruetta and the co-conspirator and seized the bags. They recovered 43 kilogram packages of cocaine and discovered another bag inside the stash house that contained 32 kilogram packages of cocaine, according to court documents.

Investigators also recovered bags of marijuana, three firearms and equipment to process large amounts of drugs, court documents show.

California

A California photographer is on a quest to photograph hundreds of native bees

LOS ANGELES (AP) — In the arid, cracked desert ground in Southern California, a tiny bee pokes its head out of a hole no larger than the tip of a crayon.

Krystle Hickman crouches over with her specialized camera fitted to capture the minute details of the bee’s antennae and fuzzy behind.

“Oh my gosh, you are so cute,” Hickman murmurs before the female sweat bee flies away.

Hickman is on a quest to document hundreds of species of native bees, which are under threat by climate change and habitat loss, some of it caused by the more recognizable and agriculturally valued honey bee — an invasive species. Of the roughly 4,000 types of bees native to North America, Hickman has photographed over 300. For about 20 of them, she’s the first to ever photograph them alive.

Through photography, she wants to raise awareness about the importance of native bees to the survival of the flora and fauna around them.

“Saving the bees means saving their entire ecosystems,” Hickman said.

Community scientists play important role in observing bees

On a Saturday in January, Hickman walked among the early wildflower bloom at Anza Borrego Desert State Park a few hundred miles east of Los Angeles, where clumps of purple verbena and patches of white primrose were blooming unusually early due to a wet winter.

Where there are flowers, there are bees.

Hickman has no formal science education and dropped out of a business program that she hated. But her passion for bees and keen observation skills made her a good community scientist, she said. In October, she published a book documenting California’s native bees, partly supported by National Geographic. She’s conducted research supported by the University of California, Irvine, and hopes to publish research notes this year on some of her discoveries.

“We’re filling in a lot of gaps,” she said of the role community scientists play in contributing knowledge alongside academics.

On a given day, she might spend 16 hours waiting beside a plant, watching as bees wake up and go about their business. They pay her no attention.

Originally from Nebraska, Hickman moved to Los Angeles to pursue acting. She began photographing honey bees in 2018, but soon realized native bees were in greater danger.

Now, she’s a bee scientist full time.

“I really think anyone could do this,” Hickman said.

A different approach

Melittologists, or people who study bees, have traditionally used pan trapping to collect and examine dead bee specimens. To officially log a new species, scientists usually must submit several bees to labs, Hickman said.

There can be small anatomical differences between species that can’t be photographed, such as the underside of a bee, Hickman said.

But Hickman is vehemently against capturing bees. She worries about harming already threatened species. Unofficially, she thinks she’s photographed at least four previously undescribed species.

Hickman said she’s angered “a few melittologists before because I won’t tell them where things are.”

Her approach has helped her forge a path as a bee behavior expert.

During her trip to Anza Borrego, Hickman noted that the bees won’t emerge from their hideouts until around 10 a.m., when the desert begins to heat up. They generally spend 20 minutes foraging and 10 minutes back in their burrows to offload pollen, she said.

“It’s really shockingly easy to make new behavioral discoveries just because no one’s looking at insects alive,” she said.

Hickman still works closely with other melittologists, often sending them photos for identification and discussing research ideas.

Christine Wilkinson, assistant curator of community science at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles, said Hickman was a perfect example of why it’s important to incorporate different perspectives in the pursuit of scientific knowledge.

“There are so many different ways of knowing and relating to the world,” Wilkinson said. “Getting engaged as a community scientist can also get people interested in and passionate about really making change.”

Declining native bees

There’s a critically endangered bee that Hickman is particularly determined to find – Bombus franklini, or Franklin’s bumblebee, last seen in 2006.

Since 2021, she’s traveled annually to the Oregon-California border to look for it.

“There’s quite a few people who think it’s extinct, but I’m being really optimistic about it,” she said.

Habitat loss, as well as competition from honey bees, have made it harder for native bees to survive. Many native bees will only drink the nectar or eat the pollen of a specific plant.

Because of her success in tracking down bees, she’s now working with various universities and community groups to help find lost species, which are bees that haven’t been documented in the wild for at least a decade.

Hickman often finds herself explaining to audiences why native bees are important. They don’t make honey, and the disappearance of a few bees might not have an apparent impact on humans.

“But things that live here, they deserve to live here. And that should be a good enough reason to protect them,” she said.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

Alabama1 week ago

Alabama1 week agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Ohio1 week ago

Ohio1 week agoOhio town launching treasure hunt for $10K worth of gold, jewelry

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThe Long Goodbye: A California Couple Self-Deports to Mexico

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoVideo: Rare Giant Phantom Jelly Spotted in Deep Waters Near Argentina

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoVideo: Farewell, Pocket Books

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Investigators Say Doorbell Camera Was Disconnected Before Nancy Guthrie’s Kidnapping

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoApple might let you use ChatGPT from CarPlay