Colorado

Opinion: Democrats, don’t break Colorado’s 81-year-old labor ceasefire

A coalition of Democratic legislators has announced plans to drop a political nuclear bomb the first week of Colorado’s legislative session, breaking an 81-year-old ceasefire between Colorado businesses and labor.

This move is bad for Colorado’s economy and the battle it starts may quickly spiral out of control.

Since 1943, Colorado has been a red state, purple state, and blue state, and during that time Colorado’s Labor Peace Act has held the middle ground, successfully governing workforce unionization in a harmonious way that may be the best such law in the country.

On one end of the political spectrum are so-called right-to-work states that prohibit mandatory union membership and the payment of union dues as a condition of employment. These laws, usually in red states, ensure employees’ rights to make their own choices regarding union affiliation. Right-to-work laws do not prevent workers from unionizing the shop floor, but the workers are not compelled to join the union or pay dues.

For many companies and site selectors looking for a new location, a right-to-work state is often among the top criteria. Today, roughly 26 states have right-to-work laws, with six of these states coming onboard within the last 14 years.

And, importantly, seven of Colorado’s top 10 competitor states are right-to-work states.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, are “union shop” states that do not have right-to-work laws in place. In these 23 states, employers and unions require workers, where applicable, to join the union or otherwise to pay union dues as a condition of employment, even if they were not union members when hired. In these states, workers may be compelled to become union members or contribute financially to the union, even if they do not want to join. These laws strengthen the union’s bargaining power and influence in the workplace.

Colorado is a unique outlier, a compromise state. It is neither a right-to-work nor union shop state. Under Colorado’s Labor Peace Act, workers can form a union with a simple majority vote, but to permit union security, which allows organized labor to deduct fees from their checks to fund the union work and bargaining activities, they must obtain a 75% vote of members.

Colorado’s balanced approach has promoted the state’s economy and brought us good jobs with good wages. While 75% is a higher bar, it seems appropriate that a higher threshold should be met before requiring all employees to pay union dues and belong to a union.

However, this coalition of politicians seeks to eliminate that second, higher-threshold vote, making it much easier for workers to unionize and fund union work and bargaining activities. Make no mistake, this is a pro-labor, anti-business bill, that will galvanize both sides and spill over to other issues with potentially adverse consequences for all.

While I was a Democrat in a Republican-controlled legislature in the 1990s, Democrats and Republicans came together to defeat right-to-work legislation. And, in 2007, when the legislature sent a union shop bill to former Democrat Gov. Bill Ritter’s desk, he vetoed it. The peace was maintained.

This is a dangerous time to tinker with Colorado’s economy. A recent 2024 CNBC analysis ranked Colorado 39th for its cost of doing business and 32nd for business friendliness. There is strong evidence from respective leaders and experts that becoming a union shop state will make it more difficult to recruit and retain Colorado businesses. Attracting companies to Colorado draws fierce competition amongst states.

Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce’s press release in response to this proposed legislation aptly noted that, Colorado “risks losing critical opportunities for job creation and economic growth” if this legislation passes. In fact, that was the primary reason why Governor Ritter vetoed it in 2007.

Between 2018 and 2023, Colorado’s average annual employment growth rate of 1.5% was more than three times that of union shop states and over 20 years was double that growth rate.

Bringing this issue forward now may also be a risky political miscalculation. In response, business leaders will likely decide to take their case directly to Colorado voters, launching an expensive and protracted right-to-work ballot measure that could succeed. It’s a real gamble that shouldn’t be ignored and would be on the ballot in 2026, a critical election year.

Rather than break this 81-year-old ceasefire, business and labor and our political leaders should sit down together, roll up their sleeves and find an appropriate off-ramp. Perhaps rather than eliminate the second vote altogether, they could simply agree to lower the threshold from 75% to 66.6% for the second vote.

Colorado law has long protected the right to organize as well as provided a path to strengthen unions through union security agreements. That’s the Colorado way and there’s no good reason to break the ceasefire here.

Doug Friednash grew up in Denver and is a partner with the law firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck. He is the former chief of staff for Gov. John Hickenlooper.

Sign up for Sound Off to get a weekly roundup of our columns, editorials and more.

To send a letter to the editor about this article, submit online or check out our guidelines for how to submit by email or mail.

Originally Published:

Colorado

Colorado family pushes for change after rare disease clinical trial abruptly ends

Colorado

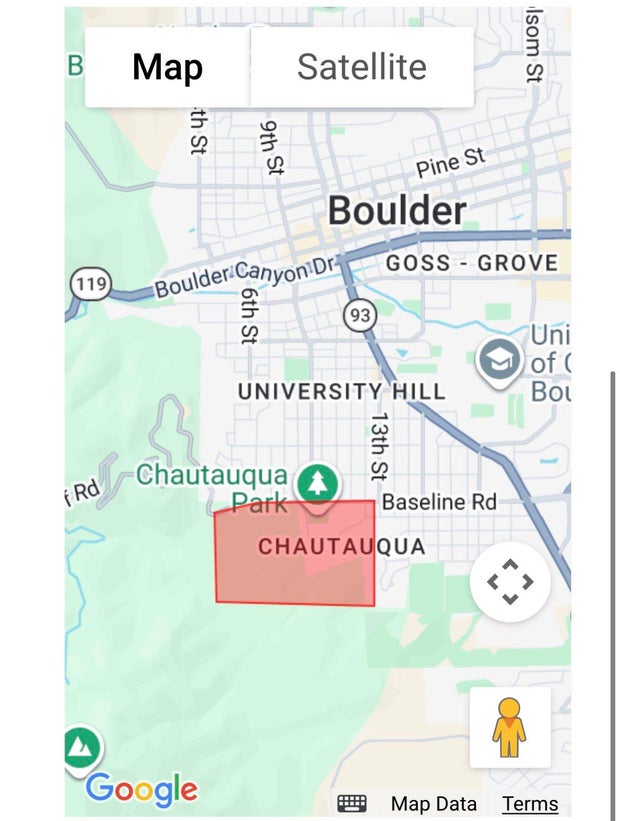

Evacuation warning issued for area near wildfire in southwest Boulder

Authorities have issued an evacuation warning for homes near a wildfire that broke out in southwest Boulder on Saturday afternoon.

Just before 1 p.m., Boulder Fire Rescue said a wildfire sparked in the southwest part of Boulder’s Chautauqua neighborhood. The Bluebell Fire is currently estimated to be approximately five acres in size, and more than 50 firefighters are working to bring it under control. Mountain View Fire Rescue is assisting Boulder firefighters with the operation.

Around 1:30, emergency officials issued an evacuation warning to the residents in the area of Chatauqua Cottages. Residents in the area should be prepared in case they need to evacuate suddenly.

Officials have ordered the DFPC Multi-Mission Aircraft (MMA) and Type 1 helicopter to assist in firefighting efforts. Boulder Fire Rescue said the fire has a moderate rate of spread and no containment update is available at this time.

Red Flag warnings remain in place for much of the Front Range as windy and dry conditions persist.

Colorado

Two-alarm fire damages hotel in Estes Park, 1 person taken to a Colorado hospital

A two-alarm fire damaged a hotel in Estes Park on Friday night. It happened at Expedition Lodge Estes Park just north of Lake Estes.

The lodge, located at 1701 North Lake Avenue on the east side of the Colorado mountain town, was evacuated after 8:30 p.m. and the fire chief said by 10 p.m. the fire was under control.

One person was hurt and taken to a hospital.

The cause of the fire is under investigation. So far it’s not clear how much damage it caused.

A total of 25 firefighters fought the blaze.

-

World4 days ago

World4 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Denver, CO4 days ago

Denver, CO4 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana6 days ago

Louisiana6 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT