Lifestyle

How to see the lost art of rebel Disney imagineer Rolly Crump in L.A.

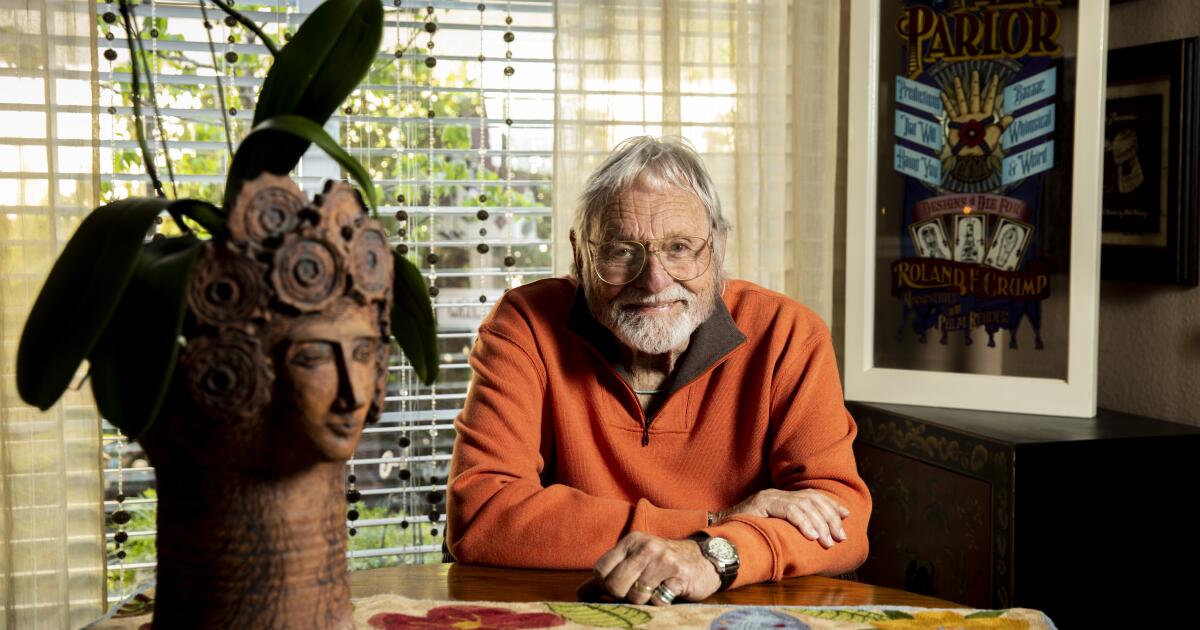

Rolly Crump had an outsized reputation. A rebel in the Disney fold. A beatnik. An unapologetic tell-it-like-it-is you-know-what.

Crump, who died last year at the age of 93, also forever changed the look of Disneyland. His art can be found in the Enchanted Tiki Room and, along with close friend and fellow artist Mary Blair, throughout It’s a Small World.

Crump’s style possessed a larger-than-life whimsy and circus-like loudness, and it caught the eye of Walt Disney, who plucked Crump from animation and one day assigned him what would become arguably the most recognizable clock in Southern California. The timepiece is the anchor of the façade of Disneyland’s It’s a Small World.

Rolly Crump designed a poster for West Hollywood folk club the Unicorn. The poster is part of a new exhibition dedicated to showing off Crump’s early work.

(From Christopher Crump)

This week, an assortment of Crump’s lesser-known personal work will be on display at West Hollywood gallery Song-Word Art House. The show, dubbed “Crump’s The Lost Exhibition,” is curated by Rolly’s son, Christopher, who followed in his father’s footsteps to work for Walt Disney Imagineering, the division of the company responsible for theme park design. “The Lost Exhibition” will draw heavily on Crump’s late-1950s and early-1960s work, specifically his series of folk-house-inspired, rock ’n’ roll-style posters.

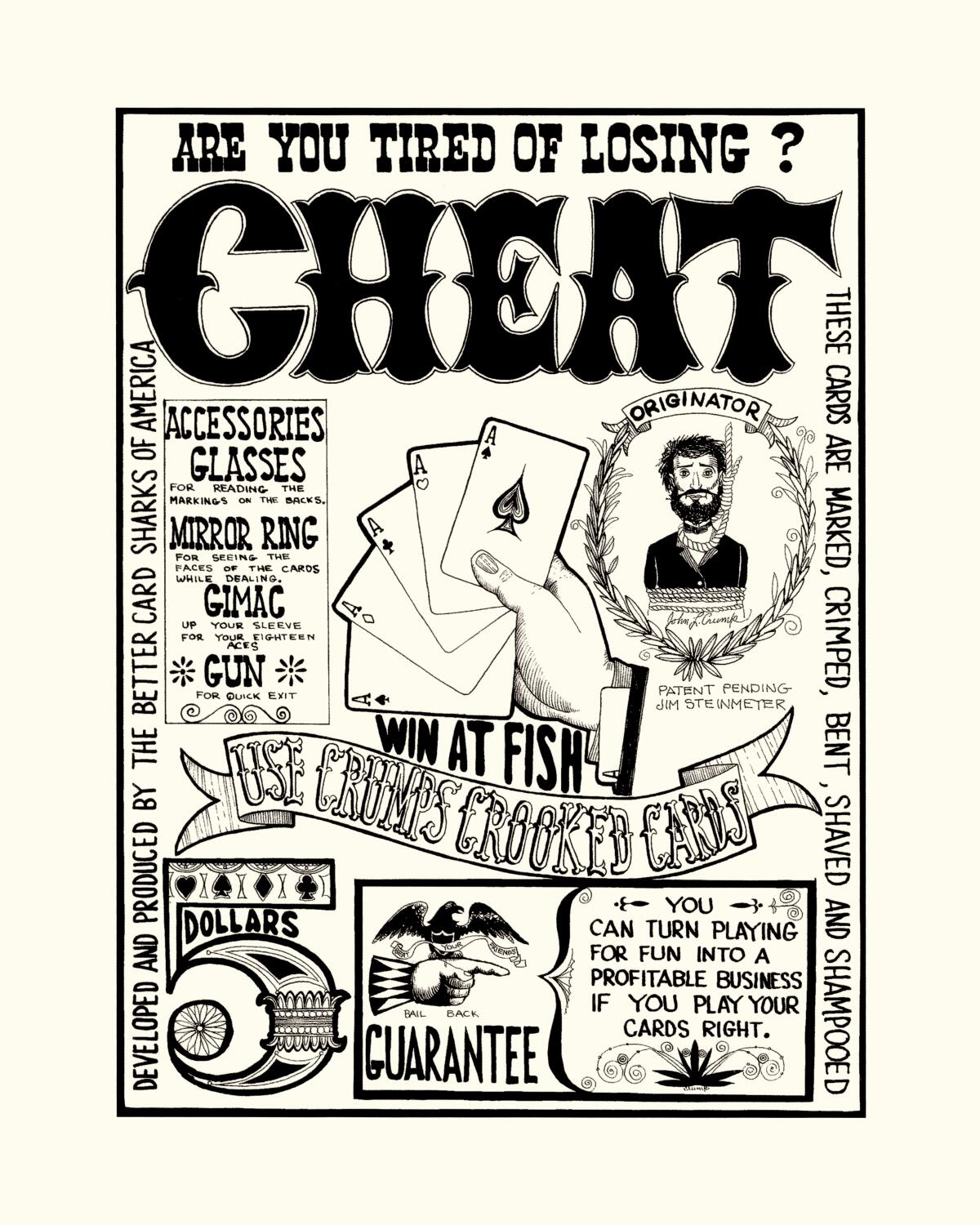

The event is open to the public Friday through Sunday, and the gallery is near the original location of one of Crump’s old hangs, folk club the Unicorn. A poster Crump drew for the venue will be a centerpiece of the exhibit. Christopher cites the freewheeling nature of the ’50s folk scene as a large influence on his father’s art, which had the sort of bold colors and intricate, line-heavy work one sees in a tattoo parlor.

Other posters show off Crump’s acidic yet silly sense of humor, such as what he called his “dopers,” that is, art that humorously celebrated drugs in the style of Beat generation barroom posters (“Be a man who dreams for himself,” reads a painting cheerleading opium).

Outside of his work at Disney, Crump continued to work on eccentric Pop art throughout his career. A comic strip-inspired 1967 poster for psychedelic rock group the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band belongs to the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. A print will be shown at Song-Word.

Crump stayed with Disney through 1970, although he would return multiple times before retiring in 1996. He also designed an attraction for Knott’s Berry Farm, briefly ran his own design firm and had a short-lived store, Crump’s, dedicated to his art. In 2017, Crump had a postcareer exhibition at the Oceanside Museum of Art, but Christopher sees “The Lost Exhibition” as a chance to explore his father’s lesser-known early work, before Crump would work on such attractions as the Haunted Mansion and It’s a Small World, the latter of which had its premiere at the 1964 World’s Fair.

“This is a personal thing for me,” Christopher says. “This is the exhibition that never happened. He should have done this. He should have had more gallery shows. The only real gallery stuff was when he had the Crump’s shop on Ventura Boulevard, but he never had a formal gallery show.”

Christopher, who will be on hand all three days to share tales about his father, spoke to The Times about the show. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Rolly Crump in his shop, Crump’s, which son Christopher said was a short-lived operation on Ventura Boulevard.

(From Christopher Crump)

Your dad started working for the Walt Disney Co. in 1952. You were born in 1954. This exhibit places a particular emphasis on artwork from that era. When did you first become aware of your father’s work?

He was drawing all the time. He supported me as a model maker, and I had a desk and tools and he bought me kits. I started building models when I was 6 years old. I watched him draw. But later, I recognized that this huge body of work of his, he was doing all the time. He hung out with [animator-artist] Walter Peregoy a lot. Walter Peregoy would get up at 4 a.m. and draw and paint. And that started hitting me. Dad had two jobs — he was working in animation and he was working in construction on the weekends, and he was knocking out all this artwork and mobiles. When someone calls themselves an artist, they don’t have a choice. It is constant. It is all the time.

You have to also think about culture. Dad wasn’t changing diapers, cooking, cleaning and washing up and all that stuff. Men didn’t do that. It wasn’t like there was something wrong with him, but it wasn’t until later where it was like, “Hey, Dad, you have to help out with the chores.” Whatever the hell Dad wanted to do, he’d do it, so in Dad’s case, he would paint, draw, sculpt and make mobiles. He was going to keep satisfying that itch of having to do that stuff.

And everybody would help. My mom did a lot of painting on my dad’s stuff. He drew it, and said, “Paint that red. Paint that green.” I remember doing colors on paintings, and this was in the early to mid ’60s. We were all part of Dad’s little art machine.

In collecting this poster art, what impresses you today? What do you appreciate about the personal work he was doing while working in animation? I remember your dad saying he felt insecure as an animator.

A Rolly Crump-designed poster that’s part of an exhibition of the artist’s early work.

(From Christopher Crump)

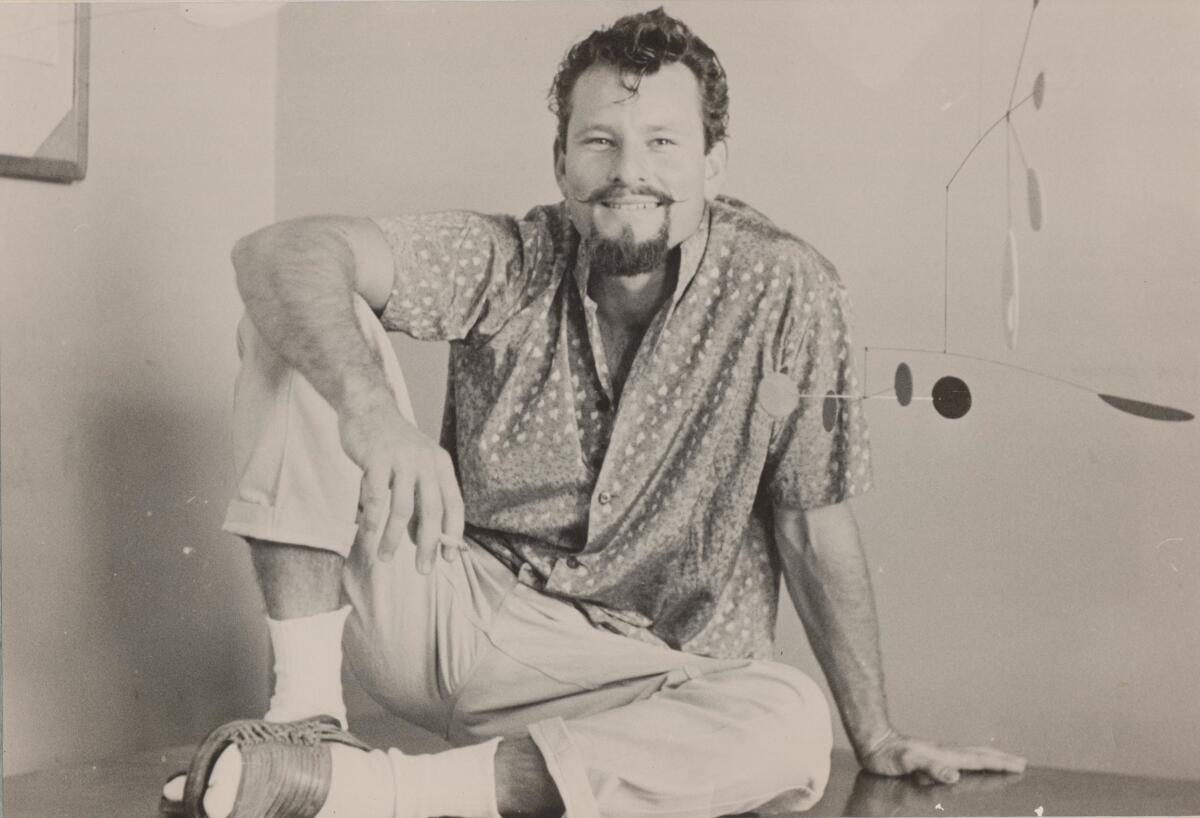

These [animation] artists — Walter Peregoy, Dale Barnhart, Frank Armitage, and of course, Ward Kimball and Marc Davis — these guys were all amazing. Dad would say, “I knew how to use a pencil.” He could draw, but he had no formal education in the arts. These guys influenced him and he learned from them, but he needed to find his voice. I captured an interview recently — somebody sent it to me — of him giving a talk, and Dad told this great story about wanting to learn how to paint, to become an artist. He was trying to mimic Walt Peregoy’s style, and it wasn’t working. He was getting really frustrated.

He talked about going to an art show at the studio, and he saw a piece of a bunch of gargoyles sitting on a log flying kites. And the light bulb went off. He said, “I can do that.” Dad’s got a funky sense of humor, and the animation world was all about getting people to laugh, so he went home and he painted lobsters drinking martinis. And that was the first painting he did where he took the idea of telling a little story and making sure it was funny. That kick-started him.

What I’ve always loved about your father’s personal work is that there’s a free-flowing nature to it. You see that even in the poster for the Unicorn. It feels improvised, jazzy.

And what I think, and I’ve heard him say this, he was always looking for something different, and then to put some twist on it. When you think about the folk era, when it was really hot — burning hot — it was hobos on freighters writing songs about social injustice. These were “stick it to the man” people. All these things influenced him — the idea of folk music and freedom of expression.

Rolly Crump in 1957, when the artist was working in animation at the Walt Disney Co.

(From Christopher Crump)

Like, there was no way he could paint like those other guys. But he found his voice, and these posters became more satirical. It’s kind of mock advertising but very tongue-in-cheek. I’ll be playing a soundtrack of a lot of the music Dad had in his collection at home. So it’s a 4½-hour compilation of Miles Davis, Nina Simone, Peter, Paul and Mary, Quincy Jones, Harry Belafonte, Wes Montgomery — all the stuff we listened to the house or I heard in his Porsche listening to the jazz station.

How do you connect what we’ll see in this show with his best-known Disney work on It’s a Small World or the Enchanted Tiki Room?

Because he was drawing every day, his line work, his composition, his technical chops as an artist got better. That led to how he was able to come up with stuff in the Tiki Room, the toys in Small World. He didn’t wake up and roll out of bed one morning and become really good. There was a gradual development of who he was. Then he got to a confidence level. He knew who he was and he was unapologetic about it.

“Crump’s The Lost Exhibition”

He started watching how Walt [Disney] behaved and he found his groove with Walt. He waited a few years before he really started becoming opinionated, and then once Walt started listening to him, it annoyed all the other Imagineers. They were all singing and dancing. “Whatever Walt wants.” Rolly wasn’t a dancer. How could this crazy beatnik character be Disney? It’s like musicians. It’s the chops. You mentioned the jazz thing — jazz is about improvisation. Jazz is about going with however the flow is going and following your crazy ideas. Walt believed in Dad’s crazy ideas.

And yet those crazy ideas helped define the tone of Disneyland. Modern theme parks are very much aligned with the look of film and television, yet there are multiple times, say, on It’s a Small World, where it’s very clear what Rolly’s influence was.

My wife didn’t know much about Disney. She rides It’s a Small World — and my dad had been doing birthday cards and Christmas cards — and she looked up at It’s a Small World and said, “Oh my God, it’s my father-in-law.” And that’s kind of my thought. This was all developed and worked out, and by the time the World’s Fair hit, and the ’60s hit, he had a good eight or nine years of messing around, and now he’s blossoming. Now he’s got a stage to work on.

So I’m talking about the ’50s and early ’60s before all that. What was it that happened to him that developed him and developed his confidence to be able to be that big-time guy?

It’d be like in music. He played a lot of little clubs before he hit the big stages. My vibe is to just kind of have people remember how artists become what they become.

Lifestyle

If you loved ‘Sinners,’ here’s what to watch next

Michael B. Jordan plays twin brothers Smoke and Stack in Sinners.

Warner Bros. Pictures

hide caption

toggle caption

Warner Bros. Pictures

Ryan Coogler’s supernatural horror stars Michael B. Jordan playing twin brothers who open a 1930s juke joint in Mississippi. Opening night does not go as planned when vampires appear outside. “In a straightforward metaphor for all the ways Black culture has been co-opted by whiteness, the raucous pleasures and sonic beauty of the juke joint attract the interest of a trio of demons … they wish to literally leech off of the talents and energy of Black folks,” writes critic Aisha Harris. The film made history with a record 16 Academy Award nominations.

We asked our NPR audience: What movie would you recommend to someone who loved Sinners? Here’s what you told us:

Near Dark (1987)

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow; starring Adrian Pasdar, Jenny Wright, Lance Henriksen

If you want another cool vampire movie with Western kind of vibes, check out Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark — super underseen and kind of hard to find, but really gritty and sexy and another very different take on what you might think is a genre that had been wrung dry. – Maggie Grossman, Chicago, Ill.

30 Days of Night (2007)

Directed by David Slade; starring Josh Hartnett, Melissa George, Danny Huston

It follows a group of people in a small Alaskan town as they struggle to survive an invasion of vampires who have taken advantage of the month-long absence of the sun. Both this and Sinners revolve around a vampire takeover and the people’s fight to outlast the “night.” – Nathan Strzelewicz, DeWitt, Mich.

The Wailing (2016)

Directed by Na Hong-jin; starring Kwak Do-won, Hwang Jung-min, Chun Woo-hee, Jun Kunimura

In this South Korean supernatural horror film, a mysterious illness causes people in a quiet rural village to become violent and murderous. A local police officer investigates while trying to save his daughter, who begins showing the same disturbing symptoms. The film blends folk horror, religion, and psychological dread, exploring themes of faith, evil, and moral weakness. Like Sinners, it centers on a supernatural force corrupting a close-knit community, builds slow-burning tension, and examines spiritual conflict and human frailty. – Amy Merke, Bronx, N.Y.

Fréwaka (2024)

Directed by Aislinn Clarke; starring Bríd Ní Neachtain, Clare Monnelly, Aleksandra Bystrzhitskaya

In this Irish folk horror film, a home care worker, Shoo, is assigned to stay with an elderly woman who’s convinced she’s under siege by malevolent fairies. Like Sinners, Fréwaka blends folk traditions and social commentary with horror. The social failures Shoo copes with (untreated mental health issues, religious abuse) are just as frightening as the supernatural forces. – Kerrin Smith, Baltimore, Md.

And a bonus pick from our critic:

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020)

Directed by George C. Wolfe; starring Viola Davis, Chadwick Boseman, Glynn Turman

This is an adaptation of August Wilson’s play about a legendary blues singer (Viola Davis) muscling through a recording session with white producers who want to control her music. Chadwick Boseman’s blistering in his final role. – Bob Mondello, NPR movie critic

Carly Rubin and Ivy Buck contributed to this project. It was edited by Clare Lombardo.

Lifestyle

Solar energy for renters has taken off in 10 states. Not in California

The tiny town of West Goshen, Calif., was exactly the kind of place that community solar was designed for.

Near Visalia, most of its 500 residents live in mobile homes, where companies won’t install rooftop panels without a solid foundation. And until recently, they used propane for heating and cooking, with price fluctuations in the winter posing hardships for low-income families.

Community solar, in which residents get a discount on their bills for subscribing as a group to small solar arrays nearby, was designed to help low-income residents, apartment dwellers, renters and others who can’t put panels on their own roofs.

Over the last 11 years, New York, Maine, Minnesota, Massachusetts and other states have built thriving community solar programs. But California has built, at most, only 34 projects since 2015, and experts say that’s a generous accounting.

“We’ve had community solar for a dozen years, and it simply has not produced anything of scale and anything of note,” said Derek Chernow, director of Californians for Local, Affordable Solar and Storage, a developer trade group that’s pushing to get a more robust program off the ground. “Projects don’t pencil out.”

The West Goshen residents were among the lucky few, becoming part of a community solar project in 2024.

“It has kind of allowed us to kind of breathe a little bit,” said resident and community organizer Melinda Metheney. Her bill has dropped by about $300 in the summer months, thanks to the 20% community solar discount, stacked with other low-income discounts and clean energy incentives, she said.

West Goshen’s panels sit about 10 miles out of town, in a field surrounded by farms. Energy and climate experts agree California must add much more clean energy to its grid, some 6 gigawatts by 2032, the California Public Utilities Commission said in a new plan last week.

Assemblymember Christopher M. Ward (D-San Diego), who in 2022 authored a bill to create a more effective community solar program, said the state needs to double its annual solar installation rate to reach that goal and is not on track to do that using only large utility-scale solar farms and individual rooftop arrays.

“We need mid-scale community solar,” he said.

Energy and climate experts agree California must add much more clean energy to its grid, some 6 gigawatts by 2032, the California Public Utilities Commission said in a new plan last week. Above, solar panels at Extra Space Storage in Pico Rivera.

(Kayla Bartkowski / Los Angeles Times)

He and a coalition of environmental groups, solar developers and the Utility Reform Network, a ratepayer advocacy group, worked to put his 2022 law into effect. They coalesced around requiring utilities to pay community solar developers and customers for the electricity they feed to the grid using the same formula they use for people who install rooftop solar.

But in May 2024, the California Public Utilities Commission decided to go with a late-in-the-game proposal backed by the state’s investor-owned utilities to pay community solar at a lower rate.

The agency, along with its public advocate’s office, argued that crediting solar developers at the higher rate would raise bills for customers who don’t have solar, who would still have to shoulder the cost of grid maintenance. It’s similar to the argument they’ve made to cut incentives for rooftop solar.

The new program relied on federal money, including the Biden administration’s Solar for All, to sweeten the deal for developers. But the utilities commission spent very little of the $250 million available under that grant before the Trump administration tried to claw it back last summer, and now it is held up in litigation.

At a legislative oversight hearing last week, Kerry Fleisher, the commission’s director of distributed energy resources, blamed the loss for the new program’s failure to launch.

“There’s been a tremendous amount of uncertainty in terms of the Solar for All funding that was intended to supplement this program,” Fleisher said. “That’s part of the reason why this has taken longer than normal.” She said the commission still plans to release a program in the next several months.

Ward, the San Diego lawmaker who wrote the community solar bill, called the program “fatally flawed” in an interview.

He’s now considering a bill to bring the community solar program more in line with what he initially envisioned — higher incentives, requirements for battery storage, and compliance with state law that mandates new houses be built with solar.

A study last year funded by a solar trade group found that could save California’s electric system $6.5 billion over 20 years. But Ward’s effort to revive his program last year failed to pass the Assembly appropriations committee.

“All the other states in our country that have adopted similar community solar program models, they are working,” said Ward, adding that 22 states have programs comparable to the one solar advocates want in California. “The writing on the wall suggests that, exactly as we feared years ago, this was not the way to go.”

California Public Utilities Commission spokesperson Terrie Prosper called California “a leader in cost-effective, least-cost solar deployment overall compared to any other state,” in an emailed statement.

Under the commission’s definition, the state has brought on 34 projects, representing 235 megawatts of community solar. But studies from groups such as the Institute for Local Self-Reliance and Wood Mackenzie use different definitions for community solar, and they show California far behind at least 10 other states.

Meanwhile, advocates and developers involved in successful community solar projects in California say they were difficult to get off the ground.

Homes in the Avocado Heights area of Los Angeles County are part of a community solar project.

(Kayla Bartkowski / Los Angeles Times)

One that came online in May in the unincorporated communities of Bassett and Avocado Heights in the San Gabriel Valley provides solar electricity to about 400 low-income residents. They get 20% discounts on their electric bills for subscribing to panels installed on two Extra Space Storage building rooftops in Pico Rivera.

Organizers said it took nearly five years to find the right location and comply with utility requirements. They also got a grant in addition to funding provided by the state utilities commission’s solar program.

It “would not have happened if it hadn’t been for the grant,” said Genaro Bugarin, a director at the Energy Coalition nonprofit that proposed and coordinated the project.

Brandon Smithwood, vice president of policy at Dimension Energy, the developer for the project in West Goshen, said he still hopes to see a community solar program in California that compensates projects for the way they help out the grid.

“We’ve seen it can work, and we know what we have won’t work,” Smithwood said at the hearing.

Lifestyle

Mundane, magic, maybe both — a new book explores ‘The Writer’s Room’

There’s a three-story house in Baltimore that looks a bit imposing. You walk up the stone steps before even getting up to the porch, and then you enter the door and you’re greeted with a glass case of literary awards. It’s The Clifton House, formerly home of Lucille Clifton.

The National Book Award-winning poet lived there with her husband, Fred, starting in 1967 until the bank foreclosed on the house in 1980. Clifton’s daughter, Sidney Clifton, has since revived the house and turned it into a cultural hub, hosting artists, readings, workshops and more. But even during a February visit, in the mid-afternoon with no organized events on, the house feels full.

The corner of Lucille Clifton’s bedroom, where she would wake up and write in the mornings

Andrew Limbong/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Limbong/NPR

“There’s a presence here,” Clifton House Executive Director Joël Díaz told me. “There’s a presence here that sits at attention.”

Sometimes, rooms where famous writers worked can be places of ineffable magic. Other times, they can just be rooms.

Princeton University Press

Katie da Cunha Lewin is the author of the new book, The Writer’s Room: The Hidden Worlds That Shape the Books We Love, which explores the appeal of these rooms. Lewin is a big Virginia Woolf fan, and the very first place Lewin visited working on the book was Monk’s House — Woolf’s summer home in Sussex, England. On the way there, there were dreams of seeing Woolf’s desk, of retracing Woolf’s steps and imagining what her creative process would feel like. It turned out to be a bit of a disappointment for Lewin — everything interesting was behind glass, she said. Still, in the book Lewin writes about how she took a picture of the room and saved it on her phone, going back to check it and re-check it, “in the hope it would allow me some of its magic.”

Let’s be real, writing is a little boring. Unlike a band on fire in the recording studio, or a painter possessed in their studio, the visual image of a writer sitting at a desk click-clacking away at a keyboard or scribbling on a piece of paper isn’t particularly exciting. And yet, the myth of the writer’s room continues to enrapture us. You can head to Massachusetts to see where Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women. Or go down to Florida to visit the home of Zora Neale Hurston. Or book a stay at the Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald Museum in Alabama, where the famous couple lived for a time. But what, exactly, is the draw?

Lewin said in an interview that whenever she was at a book event or an author reading, an audience question about the writer’s writing space came up. And yes, some of this is basic fan-driven curiosity. But also “it started to occur to me that it was a central mystery about writing, as if writing is a magic thing that just happens rather than actually labor,” she said.

In a lot of ways, the book is a debunking of the myths we’re presented about writers in their rooms. She writes about the types of writers who couldn’t lock themselves in an office for hours on end, and instead had to find moments in-between to work on their art. She covers the writers who make a big show of their rooms, as a way to seem more writerly. She writes about writers who have had their homes and rooms preserved, versus the ones whose rooms have been lost to time and new real estate developments. The central argument of the book is that there is no magic formula to writing — that there is no daily to-do list to follow, no just-right office chair to buy in order to become a writer. You just have to write.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Wisconsin4 days ago

Wisconsin4 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Florida4 days ago

Florida4 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Oregon6 days ago

Oregon6 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling