Colorado

Home insurance is getting more and more expensive in Colorado. Widfires and hail are to blame

State officials estimate that half of Colorado’s population lives in areas considered high-risk for wildfire. That, combined with a seemingly growing propensity for blazes, has resulted in rising costs to insure homes — an increase of more than 50 percent over the last three years, according to the division of insurance.

“It’s a cliche, but it’s the perfect storm — not only do we have escalating catastrophe risk from wildfire, but there’s also the market conditions, where we’re seeing skyrocketing inflation,” said Carole Walker, the executive director of the Rocky Mountain Insurance Information Association, a clearinghouse located south of Denver. “We still have COVID supply chain issues where there’s shortages, everything from drywall to lumber to labor. These are all things that are affecting what we pay for property insurance.”

Walker spoke with Colorado Matters senior host Ryan Warner about the impact of catastrophes like wildfire and hail on home and property owners and the industry. While it might be easy to envision insurance companies making massive profits from customer premiums, Walker says that isn’t the case in Colorado, where the profit margin is the third-lowest in the nation.

“No one expects you to feel sorry for your insurance company; you know, you love to hate on your insurance company,” Walker said. “But in fact, insurance companies are losing money … over the last 10 years, they’ve lost an average of 12 percent on the property insurance market, some years much more than that.”

Walker talked about some possible solutions for the issue of escalating insurance costs. This last session, state legislators passed the Fair Access to Insurance Requirements plan, which will provide policies and coverage for state homeowners unable to get insurance on the private marketplace.

Another avenue is mitigation, in which homeowners take steps to lessen the risks that wildfire might cause. That could mean things as simple as moving wood piles and removing pine needles from the roof, to installing a more fire-resistant roof altogether. Walker added that increasingly, entire neighborhoods are banding together to increase safety.

“These are all things that we need to not be doing just as a homeowner, but as the entire community because fire knows no boundaries,” Walker said. “Even if you’re doing everything great, if your neighbor isn’t, that fire’s going to spread.”

Read the interview

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ryan Warner: Homeowners’ premiums are up almost 52 percent in Colorado in three years, according to the division of insurance. That’s assuming you can find a company that’ll underwrite. Let’s run through why, and perhaps we can start with severe weather fueled by climate change.

Carole Walker: Unfortunately, what we’re living in Colorado is impacting what you pay for insurance because what we’re charged is what the insurance companies anticipate they’ll need to pay out in claims. And it’s a cliche, Ryan, but it’s the perfect storm. Not only do we have escalating catastrophe risk from wildfire, we’re number two in the nation for hail insurance claims, but also the market conditions where we’re seeing skyrocketing inflation. We still have COVID supply chain issues where there’s shortages, everything from drywall to lumber to labor. These are all things that are affecting what we pay for property insurance, and unfortunately, it puts pressure on the marketplace as insurance companies grapple with trying to balance those market conditions and the severity of that with our escalating catastrophe risk and the propensity that we’re going to have to pay more clients.

Let’s talk about inflation. I just want to put a finer point on that. If construction materials are more expensive, and frankly, labor is more expensive, and the supply chain is sort of choked up, all of those things affect the cost of repairing and rebuilding, which plays into insurance. Do I have that right?

Yes, what your insurance company cares about is not the market value of your home, but it’s the cost to repair and rebuild your home or your business in today’s dollars, and unfortunately, we’re living in larger, more expensive homes, the cost associated with repair and rebuild is higher. Again, we have contractor shortages and delays. These are all things that make insurance more expensive because not only are we seeing an increase in the number of claims because of increased catastrophes, but the cost to pay those clients.

Is this also about where we live, that many of us are choosing to live in wildfire-prone areas in particular?

Absolutely. We have more homes, more cars, more businesses in the path of those fires. So everyone wants to live in Colorado, right? And unfortunately, the State Forest Service estimates that half of our population lives in what is considered a high-risk wildfire area. Add hail to that. Unfortunately, our booming population and more people moving into these areas, and it’s not just our mountain communities and our foothills for wildfire risk, as we saw play out with the Marshall Fire last year and years ago in the Waldo Canyon Fire. These are urban suburban neighborhoods with many homes in them, and the chance of having a catastrophic wildfire is very high.

We’ll get back to hail in a moment, but perhaps you can hear eyes rolling across Colorado right now as people think about “poor insurance companies.” I mean, I think a natural reaction to seeing your rates skyrocket or your coverage disappear is ‘These companies simply aren’t making money hand over fist, and so they’re leaving or they’re raising rates. I don’t feel sorry for insurance companies.’ What is the profit picture in Colorado?

No one expects you to feel sorry for your insurance company. You love to hate on your insurance company. It’s a product you buy hoping you will never have to use. But in fact, insurance companies are losing money, especially in places like Colorado, where the profitability picture is very bleak. Colorado is ranked third worst in the nation for profitability. Over the last 10 years, they’ve lost an average 12 percent on the property insurance market, some years much more than that.

So as you continue a pattern of paying out more in claims and the anticipation of that next big catastrophic event is very high, at some point we reach that tipping point where insurance companies have to make business decisions and for all of us, what that means is I think we do have to adjust to this new normal where our homes are, for most of us, our largest asset, and we’re going to have to figure out within that household budget that insurance premiums will be higher because we don’t want that next Marshall Fire and have insurance companies not in the business of insurance in Colorado, but not able to pay those claims.

In places like Louisiana, where they haven’t done a good job of balancing those scales, they have insolvencies every week announced from insurance companies. In other places like California and Florida, where there’s not just catastrophic issues but also statutory and regulatory issues which have made it a tough place to do business, we are seeing insurance companies leave. In Colorado, we have an opportunity to do better and talk about some real solutions about how to keep a competitive, stable market, keep insurance companies at least on the profitable black side of things, and keep people in insurance and in their homes and able to pay out their mortgage.

This past session, Colorado lawmakers created it, essentially an insurer of last resort, something known as the FAIR Plan, Fair Access to Insurance Requirements. The state tells companies to bind together and share the risk. Is that the sort of solution you’re talking about?

Yes. A FAIR Plan, and we have them in up to 40 states, is a state insurer of last resort, and it seems counterintuitive, Ryan. That’s the challenging part because it really needs to be an insurer of last resort for property, not an insurer of choice. We’ve seen mistakes made in places like Florida, where there’s so much political pressure to make it the biggest insurer in the state. Really, what we need to do is have a pressure valve release for people who truly need it.

Within the bill that the legislature passed last year, it has restrictions in it to limit the number of people in the FAIR Plan, so frankly, it doesn’t go bankrupt and could bankrupt the state, and they’re charging rates that they need to charge to be able to pay out claims. You have to have at least three declinations from three private insurers. There’s caps for property of $750,000 for a residential property for insurance, $2 million for a business.

So we think that the legislature got it right in terms of keeping this a small fund from the state for people who truly can’t find insurance elsewhere and it doesn’t compete with the private market. But if we let go of those reigns we go down the road of Florida or Louisiana, we could be in real trouble. What we’re really trying to do is keep the private competitive market here and have a solution for people who truly need it, and then get them out of the FAIR Plan and back into the private market.

Do you think a day will come when the availability of insurance or the lack of it winds up dictating where people live? Like you can build a house there, you can move into a place there, but you’re not going to be able to get a mortgage because you’re not going to be able to get insurance?

There’s no silver bullet to these things. More people are moving into high-risk areas, and what we define as a high-risk area is also evolving. So we need to be working together as developers, planners, and also consider what does that look like for the people that live in there, especially as we do new construction and develop in high-risk places, whether that’s a hurricane-prone area or a wildfire-prone area. The good news for those of us that live in the high-risk wildfire areas is the science shows us there is much we can do to put the odds in our favor of not losing a home in a wildfire.

There are scientifically proven steps for mitigation, and if you’re doing them on an individual property as a homeowner, if the entire community is banding together, and that as a state we’re looking at how we actually reduce the risk of wildfire, that’s where we start to get to some real solutions. So these just can’t be insurance solutions. Those are temporary solutions. Insurance companies are just responding to a more challenging marketplace. On the other side of things, we as a country and a state and communities and homeowners need to be following the science and doing the mitigation. So do we have to look at where people are living? Absolutely, but we also have to look at what we’re doing from a mitigation standpoint to make these communities and homes safer.

When I sign up for health insurance, they often ask if I’m a smoker, and that affects my rates. And when I sign up for automobile insurance, they say, “Do you wear your seatbelt or do you have accidents in the past?” These are elements that affect the cost of a policy.

So, does fireproofing a home, I’ve heard this called hardening a home, against wildfire, will that affect availability and rates specifically?

So insurance is the financial incentive to do the right thing when it comes to wildfire mitigation. It started back after the Hayman Fire in 2000, where insurance companies started requiring mitigation to get and keep affordable insurance. Now, most companies have those programs and notifications in place, so if you live in a wildfire-prone area, you’ve received that notification or even, unfortunately, a non-renewal because you’re unwilling to do the proper mitigation. So it’s the right thing to do from a risk standpoint. It’s also the right thing to do from a financial standpoint. Not only will it help you keep insurance, but it will help you keep insurance with what we call a preferred or more standard insurance company, which keeps your rates lower.

I think it’s important to say that there are individual actions a homeowner can take, and then I think you alluded to the notion of a community taking action so that the hardening, if you will, against wildfire is true across a town, for instance. And given how we know that a fire can spread, those collective actions are important too. Speak to those for a bit.

That’s absolutely a parallel track to the real solution of reducing risk. If an individual homeowner does all the right things, some of them are common sense things, get the needles off the roof, mow the grass, get the wood pile off the wood deck. But some of these things are more impactful absolutely if the entire community is doing it.

There was a bill actually passed this last session that will offer grants to community mitigation programs and individuals that do home hardening because some of those common sense things are great, but also because of our high risk, it may require an investment of a new roof that’s more fire resistant, fire resistant plants, retaining walls depending on your risk. These are all things that we need to not be doing just as a homeowner but the entire community, because fire knows no boundaries. You’re doing everything great, if your neighbor isn’t, that fire’s going to spread. As we saw in the Marshall Fire, it ran along a fence line. We had a densely populated area, so with this bill that was passed for home hardening, that’s going to help.

There was also another bill passed that will create what we call a WUI, which means Wildland Urban Interface, statewide board that will at least have a common low denominator of what codes we should have for building across the state that will be more fire-resistant.

Some concrete actions there. I do want to talk about hail. You refer to the Front Range and frankly the whole corridor as “Hail Alley.” Is hail something you can harden yourself against?

It actually is. Fire is a much better example because there’s so much we can do to put the odds in our favor, but when it comes to hail and at least the roof, which is the most vulnerable part of your home, we have testing for hail-impact-resistant roofs and property. So there’s actually an insurance industry lab down in South Carolina where we start ember fires, we recreate hail storms, and it shows us that there are products that will make our homes more hail resistant. So that’s something we also need to be looking at and investing in here in Hail Alley.

And hail is the biggest source of loss in Colorado?

It still is. Historically, it’s our most expensive insured catastrophe. The biggest of them all so far, anyway, was May of 2017, where we had $2.4 billion from one 45-minute hailstorm because it cut such a wide swath across the state.

Colorado

5 dog-friendly trails to check out in and near Fort Collins

Tips on keeping your dog safe during the summer

From fresh water to hot pavement, here are a few things to keep in mind when it comes to dogs, heat and summer.

- Five dog-friendly trails in or near Fort Collins, Colorado, offer various hiking experiences.

- Options range from short loops to longer trails, some with water access for dogs.

The only thing better than hiking the many Fort Collins-area trails is doing it with your dog.

Here are five favorite dog-friendly trails in or near Fort Collins to check out.

Dogs must be on a leash and though rare, rattlesnakes can be found on all of these trails, so stay on the trail and be vigilant. These are all multiuse trails, so make sure to have control of your dog.

Horsetooth Falls Loop

- Where: Horsetooth Mountain Open Space. West of Horsetooth Reservoir

- The hike: You have options. It’s an easy 1.1 miles one way on a nonpaved trail to the falls, which you and your dog will find refreshing after the sunny hike. Either head back the way you came or do the moderate 3.1-mile loop via the Spring Creek, Horsetooth Rock and South Ridge trails back to the parking lot. The trail to the falls can be crowded.

- Fee: $10 for county resident daily permit.

- Information: Visit the Larimer County website.

Want a preview? Check out this video from 2021:

See why Horsetooth Falls hike is the best in years

Abundant spring rain has the falls flowing, vistas vibrant green and the wildflowers blooming.

Miles Blumhardt, Fort Collins Coloradoan

Pineridge Natural Area

- Where: On the western edge of Fort Collins. The main parking lot is on Larimer County Road 42C (approximate address is 2750 County Road 42C).

- The hike: Your dog will enjoy splashing in Dixon Reservoir and its 1.8-mile, nonpaved loop. If you wish to venture farther, there are more soft surface trails found on the 9.6-mile Foothills Trail that connects Pineridge, Maxwell and Reservoir Ridge natural areas. There is little shade on this hike, so mornings and evenings are better options.

- Fee: Free.

- Hours: 5 a.m. to 11 p.m.

- Information: Visit the Fort Collins Natural Areas web page for Pineridge Natural Area.

Lory State Park East/West Valley trails

- Where: Just west of Horsetooth Reservoir, 708 Lodgepole Drive.

-

The hike: The easy, 2.2-mile East Valley Trail takes you on a nonpaved trail to the shores of Horsetooth Reservoir, where your dog can enjoy the water (but not at designated human swimming areas). You can either head back the same way or add the 2.3-mile, nonpaved West Valley Loop back for a more difficult route. No shade, so enjoy the water.

- Fee: $10 daily vehicle pass.

- Hours: 5 a.m. to sunset.

- Information: Visit the Colorado Parks and Wildlife web page for Lory State Park.

Reservoir Ridge Natural Area

- Where: Parking lots on Centennial Drive/Larimer County Road 23, the west end of Michaud Lane and off Overland Trail Road (at approximately 1425 Overland Trail Road).

- The hike: About 5 miles of nonpaved trail takes you along the foothills with great views of Fort Collins. There is no water and little shade on this hike, so early morning and late evening are best. This trail connects to the 9.6-mile Foothills Trail.

- Fee: Free.

- Hours: 5 a.m. to 11 p.m.

- Information: Visit the Fort Collins Natural Areas web page for Reservoir Ridge Natural Area.

Arapaho Bend Natural Area

- Where: East side of Fort Collins near Interstate 25. Parking lots at the east end of Horsetooth Road, Strauss Cabin Road between Horsetooth Road and Harmony Road, and one at the Harmony Transfer Center.

- The hike: If pressed for time, this is a good go-to. It includes a mix of 4 miles of paved and nonpaved trails that wind among ponds, Rigden Reservoir and the Poudre River, with some shade provided by large cottonwood trees.

- Fee: Free.

- Hours: 5 a.m. to 11 p.m.

- Information: Visit the Fort Collins Natural Areas web page for Arapaho Bend Natural Area.

Colorado

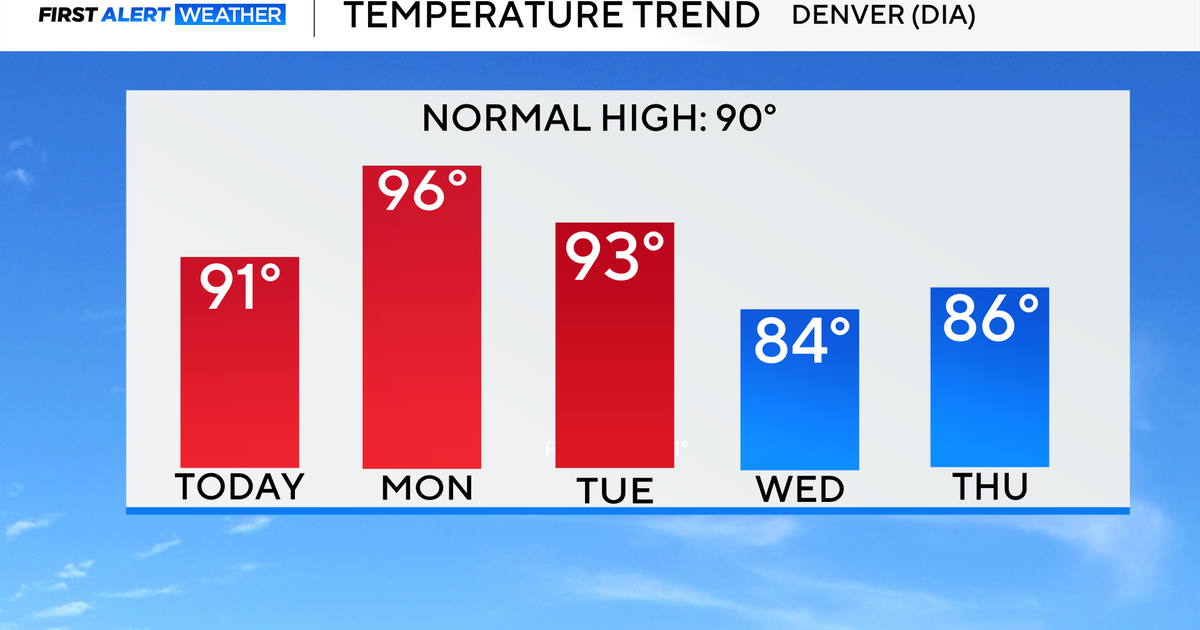

Colorado Weather: 90s Heat Returns

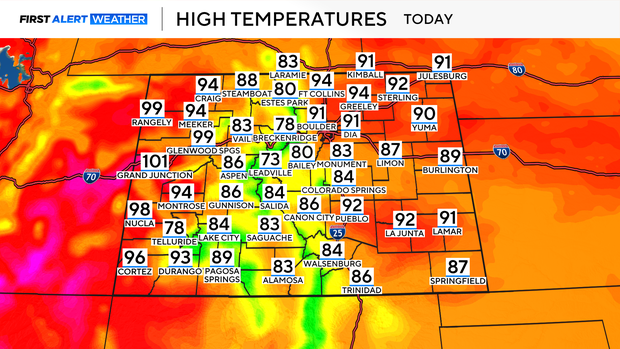

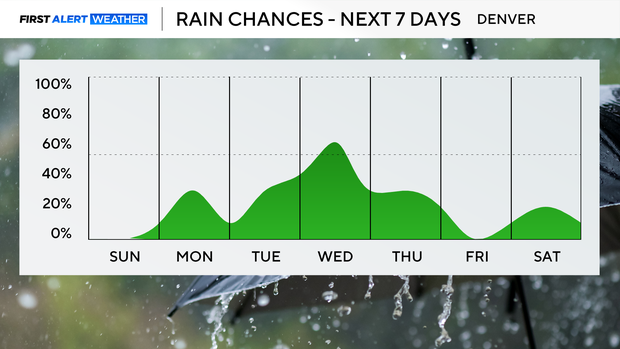

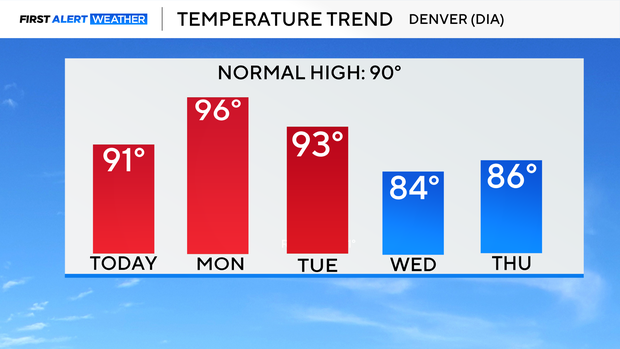

Colorado is turning up the heat this week. Expect temperatures in the 90s across the Denver metro area and plains through Tuesday.

CBS

There’s a chance for isolated showers and storms Monday and Tuesday. The best chance for rain in Denver and the plains arrives mid‑week. Wednesday’s forecast shows a mid‑afternoon thunderstorm rolling through, potentially bringing hail and gusty winds to lower elevations.

CBS

By Wednesday, highs dip to the lower 80s and upper 70s offering a bit of relief from the heat . However, this cooldown is short‑lived. Expect temperatures to rebound into the mid to upper 80s on Thursday and bounce into the low 90s Friday and Saturday.

CBS

Colorado

Man sentenced to 48 years for attempting to traffic 100K fentanyl pills to Colorado

WELD COUNTY, Colo. (KKTV) – A Denver man was sentenced to 48 years in prison after pleading guilty to attempting to traffic illegal drugs to Weld County, according to the 19th Judicial District Attorney’s Office.

The DA said Colorado State Troopers pulled over Miguel Gutierrez-Heredia in Fruita on March 26, 2024, for going 93 mph in a 75 mph speed zone.

At the time of the traffic stop, the DA says authorities were tracking his whereabouts in connection with a drug trafficking investigation. Investigators concluded that Gutierrez-Heredia had gone to California to pick up narcotics that would eventually be distributed in Denver and Northern Colorado.

During the traffic stop, authorities reportedly found nearly 100,000 fentanyl pills, nearly five pounds of cocaine, and more than two and a half pounds of methamphetamine in Gutierrez-Heredia’s vehicle.

Gutierrez-Heredia pled guilty in May to one count of conspiracy to sell or distribute fentanyl – more than 50 grams, one count of special offender – introducing or importing to the state of Colorado, and one count of possession with intent to sell or distribute methamphetamine – more than 14 grams but less than 225 grams.

“At the time of this interception, this was one of the biggest fentanyl busts in the state,” Chief Deputy District Attorney Michael Pirraglia said.

District Attorney Pirraglia and Deputy District Attorney Katherine Fitzgerald prosecuted this case. Weld County District Court Judge Vincente Vigil handed down the sentence.

Copyright 2025 KKTV. All rights reserved.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoVideo: Trump Signs the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Into Law

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoOpinion | The Ugliness of the ‘Big, Beautiful’ Bill, in Charts

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,227

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoVideo: Trump Compliments President of Liberia on His ‘Beautiful English’

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoCyberpunk Edgerunners 2 will be even sadder and bloodier

-

Business1 week ago

Companies keep slashing jobs. How worried should workers be about AI replacing them?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTexas Flooding Map: See How the Floodwaters Rose Along the Guadalupe River

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoDeath toll from Texas floods rises to 24 as search underway for more than 20 girls unaccounted for | CNN