On a sunny morning two years ago, a group of state officials stood in the mountains of northwestern Colorado in front of a handful of large metal crates. With a small crowd watching them, the officials began to unlatch the crate doors one by one. Out of each came a gray wolf — arguably the nation’s most controversial endangered species.

Colorado

Colorado has wolves again for the first time in 80 years. Why are they dying?

This was a massive moment for conservation.

While gray wolves once ranged throughout much of the Lower 48, a government-backed extermination campaign wiped most of them out in the 19th and 20th centuries. By the 1940s, Colorado had lost all of its resident wolves.

But, in the fall of 2020, Colorado voters did something unprecedented: They passed a ballot measure to reintroduce gray wolves to the state. This wasn’t just about having wolves on the landscape to admire, but about restoring the ecosystems that we’ve broken and the biodiversity we’ve lost. As apex predators, wolves help keep an entire ecosystem in balance, in part by limiting populations of deer and elk that can damage vegetation, spread disease, and cause car accidents.

In the winter of 2023, state officials released 10 gray wolves flown in from Oregon onto public land in northwestern Colorado. And in January of this year, they introduced another 15 that were brought in from Canada. Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) — the state wildlife agency leading the reintroduction program — plans to release 30 to 50 wolves over three to five years to establish a permanent breeding population that can eventually survive without intervention.

“Today, history was made in Colorado,” Colorado Governor Jared Polis said following the release. “For the first time since the 1940s, the howl of wolves will officially return to western Colorado.”

Fast forward to today, and that program seems, at least on the surface, like a mess.

Ten of the transplanted wolves are already dead, as is one of their offspring. And now, the state is struggling to find new wolves to ship to Colorado for the next phase of reintroduction. Meanwhile, the program has cost millions of dollars more than expected.

The takeaway is not that releasing wolves in Colorado was, or is now, a bad idea. Rather, the challenges facing this first-of-its-kind reintroduction just reveal how extraordinarily difficult it is to restore top predators to a landscape dominated by humans. That’s true in the Western US and everywhere — especially when the animal in question has been vilified for generations.

Why 10 of the reintroduced wolves are already dead

One harsh reality is that a lot of wolves die naturally, such as from disease, killing each other over territory, and other predators, said Joanna Lambert, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Colorado Boulder. Of Colorado’s new population, one of the released wolves was killed by another wolf, whereas two were likely killed by mountain lions, according to Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

The changes that humans have made to the landscape only make it harder for these animals to survive. One of the animals, a male found dead in May, was likely killed by a car, state officials said. Another died after stepping into a coyote foothold trap. Two other wolves, meanwhile, were killed, ironically, by officials. Officials from CPW shot and killed one wolf — the offspring of a released individual — in Colorado, and the US Department of Agriculture killed another that traveled into Wyoming, after linking the wolves to livestock attacks. (An obscure USDA division called Wildlife Services kills hundreds of thousands, and sometimes millions, of wild animals a year that it deems dangerous to humans or industry, as my colleague Kenny Torella has reported.)

Yet, another wolf was killed after trekking into Wyoming, a state where it’s largely legal to kill them.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife has, to its credit, tried hard to stop wolves from harming farm animals. The agency has hired livestock patrols called “range riders,” for example, to protect herds. But these solutions are imperfect, especially when the landscape is blanketed in ranchland. Wolves still kill sheep and cattle.

This same conflict — or the perception of it — is what has complicated other attempts to bring back predators, such as jaguars in Arizona and grizzly bears in Washington. And wolves are arguably even more contentious. “This was not ever going to be easy,” Lambert said of the reintroduction program.

Colorado is struggling to find more wolves to ship in

There’s another problem: Colorado doesn’t have access to more wolves.

The state is planning to release another 10 to 15 animals early next year. And initially, those wolves were going to come from Canada. But in October, the Trump administration told CPW that it can only import wolves from certain regions of the US. Brian Nesvik, director of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, a federal agency that oversees endangered species, said that a federal regulation governing Colorado’s gray wolf population doesn’t explicitly allow CPW to source wolves from Canada. (Environmental legal groups disagree with his claim).

So Colorado turned to Washington state for wolves instead.

But that didn’t work either. Earlier this month, Washington state wildlife officials voted against exporting some of their wolves to Colorado. Washington has more than 200 gray wolves, but the most recent count showed a population decline. That’s one reason why officials were hesitant to support a plan that would further shrink the state’s wolf numbers, especially because there’s a chance they may die in Colorado.

Some other states home to gray wolves, such as Montana and Wyoming, have previously said they won’t give Colorado any of their animals for reasons that are not entirely clear. Nonetheless, Colorado is still preparing to release wolves this winter as it looks for alternative sources, according to CPW spokesperson Luke Perkins.

Ultimately, Lambert said, it’s going to take years to be able to say with any kind of certainty whether or not the reintroduction program was successful.

“This is a long game,” she said.

And despite the program’s challenges, there’s at least one reason to suspect it’s working: puppies.

Over the summer, CPW shared footage from a trail camera of three wolf puppies stumbling over their giant paws, itching, and play-biting each other. CPW says there are now four litters in Colorado, a sign that the predators are settling in and making a home for themselves.

“This reproduction is really key,” Eric Odell, wolf conservation program manager for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, said in a public meeting in July. “Despite some things that you may hear, not all aspects of wolf management have been a failure. We’re working towards success.”

Colorado

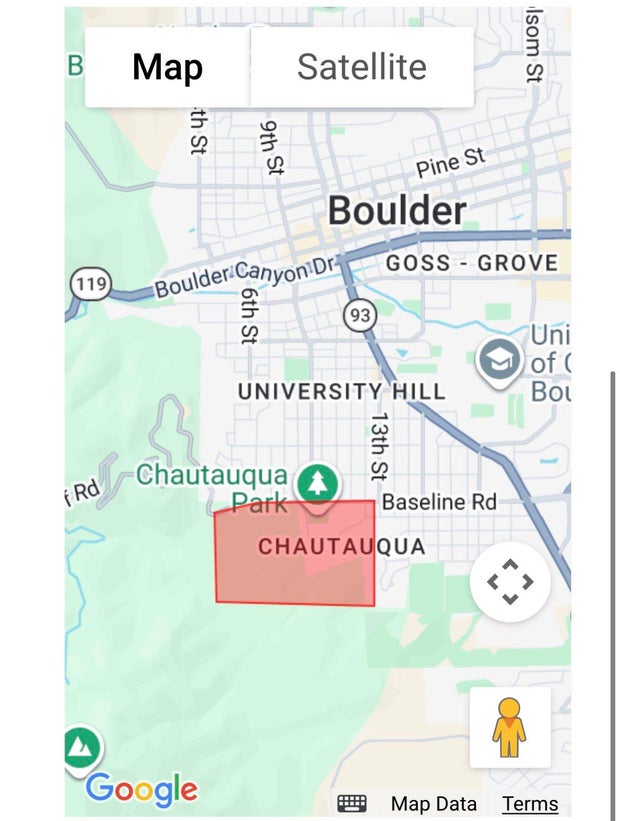

Evacuation warning issued for area near wildfire in southwest Boulder

Authorities have issued an evacuation warning for homes near a wildfire that broke out in southwest Boulder on Saturday afternoon.

Just before 1 p.m., Boulder Fire Rescue said a wildfire sparked in the southwest part of Boulder’s Chautauqua neighborhood. The Bluebell Fire is currently estimated to be approximately five acres in size, and more than 50 firefighters are working to bring it under control. Mountain View Fire Rescue is assisting Boulder firefighters with the operation.

Around 1:30, emergency officials issued an evacuation warning to the residents in the area of Chatauqua Cottages. Residents in the area should be prepared in case they need to evacuate suddenly.

Officials have ordered the DFPC Multi-Mission Aircraft (MMA) and Type 1 helicopter to assist in firefighting efforts. Boulder Fire Rescue said the fire has a moderate rate of spread and no containment update is available at this time.

Red Flag warnings remain in place for much of the Front Range as windy and dry conditions persist.

Colorado

Two-alarm fire damages hotel in Estes Park, 1 person taken to a Colorado hospital

A two-alarm fire damaged a hotel in Estes Park on Friday night. It happened at Expedition Lodge Estes Park just north of Lake Estes.

The lodge, located at 1701 North Lake Avenue on the east side of the Colorado mountain town, was evacuated after 8:30 p.m. and the fire chief said by 10 p.m. the fire was under control.

One person was hurt and taken to a hospital.

The cause of the fire is under investigation. So far it’s not clear how much damage it caused.

A total of 25 firefighters fought the blaze.

Colorado

Warm storm delivers modest totals to Colorado’s northern mountains

Lucas Herbert/Arapahoe Basin Ski Area

Friday morning wrapped up a warm storm across Colorado’s northern and central mountains, bringing totals of up to 10 inches of snowfall for several resorts.

Higher elevation areas of the northern mountains — particularly those in and near Summit County and closer to the Continental Divide — received the most amount of snow, with Copper, Winter Park and Breckenridge mountains seeing among the highest totals.

Meanwhile, lower base areas and valleys received rain and cloudy skies, thanks to a warmer storm with a snow line of roughly 9,000 feet.

Earlier this week, OpenSnow meteorologists predicted the storm’s snow totals would be around 5-10 inches, closely matching actual totals for the northern mountains. The central mountains all saw less than 5 inches of snow.

Here’s how much snow fell between Wednesday through Friday morning for some Western Slope mountains, according to a Friday report from OpenSnow:

Aspen Mountain: 0.5 inches

Snowmass: 0.5 inches

Copper Mountain: 10 inches

Winter Park: 9 inches

Breckenridge Ski Resort: 9 inches

Arapahoe Basin Ski Area: 8.5 inches

Keystone Resort: 8 inches

Loveland Ski Area: 7 inches

Vail Mountain: 7 inches

Steamboat Resort: 6 inches

Beaver Creek: 6 inches

Irwin: 4.5 inches

Cooper Mountain: 4 inches

Sunlight: 0.5 inches

Friday and Saturday will be dry, while Sunday will bring northern showers. The next storms are forecast to be around March 3-4 and March 6-7, both favoring the northern mountains.

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana6 days ago

Louisiana6 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO3 days ago

Denver, CO3 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT