Alaska

How Warming Ruined a Crab Fishery and Hurt an Alaskan Town

On a normal winter day on St. Paul, an island in the Bering Sea some 300 miles off the Alaskan coast, the community would be humming with activity. At the Trident Seafood crab processing plant, the diesel engines of commercial crab boats would be gurgling, and lifts would be running nonstop, transferring thousands of pounds of snow crab into the plant. “Those sounds are a reminder that money is coming in,” St. Paul’s city manager, Phil Zavadil, said in February from his office in city hall. But instead, St. Paul, a mostly Aleut community of just under 500, was silent. From “an environmental aesthetic point of view,” Zavadil admitted, the quiet was nice. “But it translates into the real-world [budget] cuts we’re experiencing now.”

In early October 2022, for the first time ever, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game canceled the Bering Sea season for snow crab (also known as opilio crab) after an annual survey revealed an almost total population collapse. No Bering Sea community was hit harder than St. Paul, whose economy relies almost entirely on snow crab, thanks to Trident, whose plant there is the largest crab processing facility in North America. Most of Trident’s some 400 workers are seasonal and come from outside St. Paul, but the facility generates millions for the city through a “landing tax” imposed on commercial fishing boats, a tax on crab sales, and fees for fuel, supplies, and support services for the snow crab fleet.

Fishermen and scientists had been growing increasingly worried about the Bering Sea’s marine ecosystem since 2013.

Heather McCarty, of the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association, which manages community fisheries allocations for St. Paul, said in February that the city’s tax revenues went from about $2.5 million two years ago to approximately $200,000 this year. “It was all snow crab all the time,” she said at the time. “[Now] they have about a year’s worth of reserves that will allow them to survive with the municipal services relatively intact, but, after that, it’s anybody’s guess how they’ll actually pay for really basic things.”

Not long after the snow crab season was canceled, Bob Foy, science and research director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, estimated that billions of crabs had been lost in just a few months’ time. “We don’t have a smoking gun, if you will,” Foy said of the collapse. “Except the heat wave.”

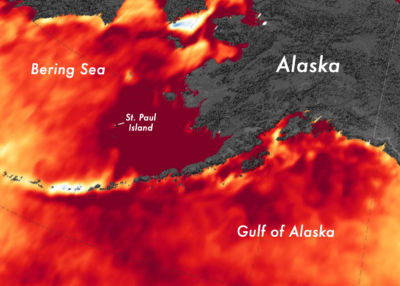

The St. Paul community, commercial fishers, and scientists like Foy had been growing increasingly worried about the Bering Sea’s marine ecosystem since 2013, when a sustained period of light winds led to the creation of a massive hot spot in the eastern Pacific Ocean. “The Blob,” as the swath of warm surface water was dubbed, turned out to not be a fleeting anomaly but a ballooning crisis. Over the next three years, it encompassed much of the North American West Coast, an area of about 3 million square miles.

St. Paul has a population of less than 500 people.

Galaxiid / Alamy Stock Photo

The world’s oceans have absorbed about 90 percent of the excess atmospheric heat generated by carbon dioxide emissions, which has manifested as an average sea surface temperature increase of 0.14 degrees per decade. When wind patterns weaken or shift, so too do ocean currents, gyres, and eddies — processes that essentially serve as the oceans’ circulation system. Dennis McGillicuddy Jr., deputy director of the Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health, describes the warming of both water and air as a kind of ever intensifying feedback loop. “The wind patterns are heavily impacted by the distribution of heat over the Earth, and since most of the heat is in the ocean, changes in the currents are going to change the heat distribution, which then feeds back on the winds,” he says. “So, it really is a very tightly coupled system.”

As waters warm and currents shift, prey species like krill decline in abundance or move to cooler water. The whales and salmon that feed on them must follow or face starvation. What may appear to be a single issue — a warming atmosphere — becomes a complex tangle stretching across ecosystems.

In parts of the Gulf of Alaska, surface temperatures one year after the emergence of The Blob had risen as much as 7 degrees F.

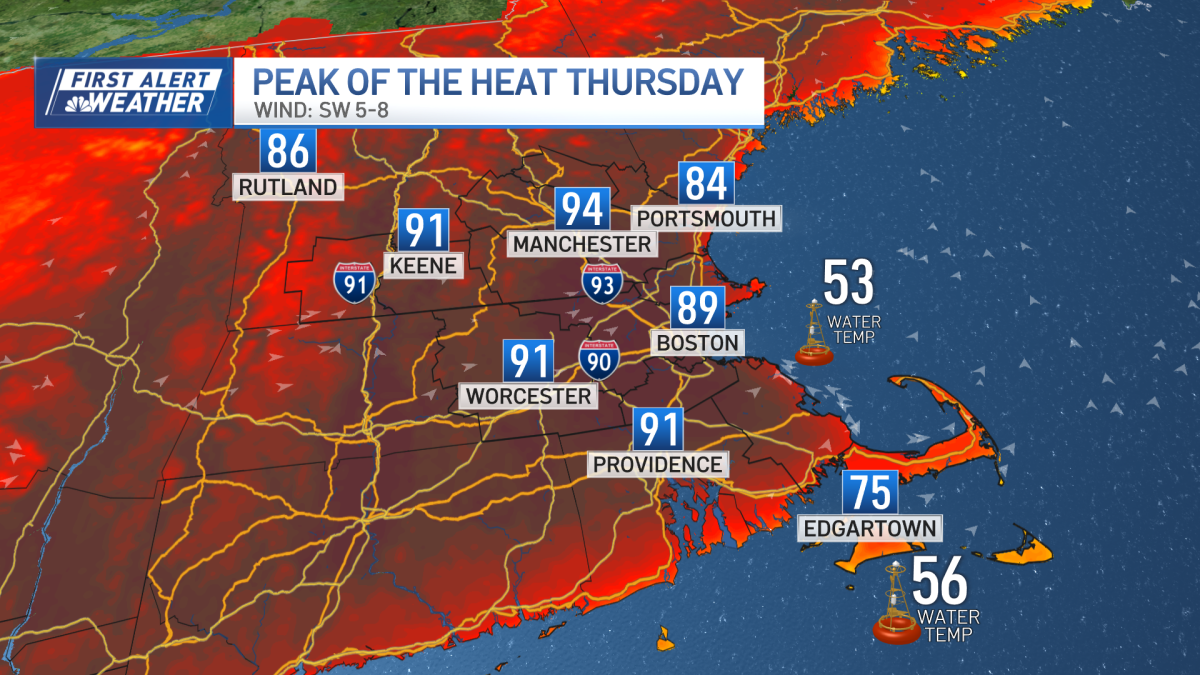

Unusually high spikes in ocean surface temperatures like The Blob are becoming all too common — according to NOAA, since 2012, strong or severe marine heat waves have become 50 percent more frequent. El Niño, a warming phenomenon driven by a sustained period of shifting winds along the equatorial Pacific, is probably the best-known producer of marine heat waves. During the 2016 El Niño event, the South Pacific islands and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef experienced catastrophic coral bleaching. Last summer’s extreme heat across Europe triggered a marine heat wave in the Mediterranean that caused mass die-offs of sponges, sea stars, and mollusks. In the North Atlantic waters off New England and eastern Canada, rising water temperatures have been dramatic and long-lasting, with cod, haddock, and lobster departing for colder waters to the northeast. Facing drops in traditional prey, the North Atlantic’s large whales are increasingly chasing less nutritious food sources closer to shore, where they are at more risk of injury from fishing gear entanglement, vessel strikes, and other human interactions.

In some parts of the Gulf of Alaska, surface temperatures one year after the emergence of The Blob had risen by as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit. Trouble quickly cascaded across the gulf’s ecosystem. Algal blooms poisoned shellfish. Krill and forage fish numbers declined, causing whales, cod, and other predator species to shift their migratory patterns in a desperate search for food. Between 2018 and 2019, NOAA recorded sustained periods of surface water temperatures of over 38 degrees F in the Gulf of Alaska, roughly 2 degrees higher than the average over the past two decades. By then, the dangerously warm water had crept through the wide passes of the eastern Aleutian Islands and began mixing with the cold waters of the Bering Sea.

A marine heat wave in August 2019. In deep red areas, the ocean surface was more than 5 degrees F warmer than normal.

NASA / Yale Environment 360

Until recently, research on marine heat waves has centered primarily on ocean surface temperatures. Observational data from satellites, buoys, and research ships have historically been focused on this area of the water column because it is an important predictor for storms and weather patterns like El Niño and La Niña. Heating or cooling in the upper layer of oceans is also a key driver of distribution shifts in species important to fin-fisheries, like tuna, salmon, and menhaden. But there is mounting evidence that heat waves can occur throughout the water column, including at the seafloor, where myriad fish and crustaceans, such as the snow crab, live.

In March, a team of scientists from NOAA, University of Colorado, and the National Center for Atmospheric Research published a study that focused on “bottom marine heat waves” along North America’s continental shelves. The researchers found these events can occur simultaneously with surface heat waves and sometimes persist even longer. The team also learned that, when a bottom marine heat wave is underway, there might be little evidence of it at the top of the water column. “That means it can be happening without managers realizing it until the impacts start to show,” the study’s lead author, Dillon Amaya, said.

“When is it not a disaster anymore?” says a representative of the fishermen’s association. “When is it just status quo?”

In the Bering Sea, the first sign of likely trouble on the seafloor was in the winter of 2018-19, when the Gulf of Alaska’s surface temperatures reached record highs. “In 2018, 2019, we saw far and away the lowest sea ice extent on record, and far and away the highest temperatures, in the Bering Sea,” says Mike Litzow, who heads NOAA’s Shellfish Assessment Program in Kodiak, Alaska and monitors snow crab populations. Though Bering Sea crab fishers have known it intuitively for decades, in 2008, Litzow and his colleague, Franz Mueter, compiled the first empirical evidence connecting sea ice with snow crab abundance. The species prefers temperatures of about 35 degrees F and below — when sea ice begins to melt, cold, dense water falls to the bottom and remains there through the summer, creating ideal living conditions for snow crab. “Snow crab are an Arctic animal, and in Alaska they only exist in waters that are seasonally ice covered,” Litzow says. “And areas with ice on the surface in the winter are much colder on the bottom in the summer.”

When I had spoken to Zavadil, the St. Paul city manager, in February, he was still holding out hope that the Bering Sea ice would show up. But when I talked with him again in May, he recalled months of dramatic swings between snow and rain, which is not characteristic of winter at such a high latitude. “We never did see the ice this year,” he said.

Fishers sort snow crabs caught in the Bering Sea.

Loren Holmes / Anchorage Daily News

Making the impacts of warmer water along the seafloor even more acute is the fact that snow crabs are a “pulse fishery,” meaning they seem to experience natural boom-and-bust cycles. No one, including scientists like Litzow, is quite sure why this happens. (Blue crabs in the Eastern U.S. have similar fluctuations in abundance.) To add to the mystery, in 2018, when so many species in the Gulf of Alaska were undergoing massive die-offs, the Bering Sea’s snow crab population had one of its biggest recruitments — or baby booms — ever recorded. Unlike past booms, however, this time, none of the juveniles survived to adulthood. “What we had this year is all these animals that were still immature, still small, just disappear,” Litzow says. “This was totally unprecedented.” He noted that loss estimates range from 10 to 40 billion animals, and no age group was spared.

The fear is that, as water temperatures continue to climb, the snow crab’s boom-and-bust cycles might become too intense to sustain a viable fishery. Says McCarty, of the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association: “When is it not a disaster anymore? When is it just status quo?”

St. Paul was approved for federal disaster aid in the wake of the snow crab collapse, but it has not yet received the money.

Another vexing, unanswered riddle is what, exactly, is killing the crabs. While overheated water is the obvious proxy, Litzow says, the actual cause of death remains an open question. There are clues, though, beginning with metabolism. In his lab in Kodiak, Litzow and his team have observed that a snow crab’s metabolic rate increases dramatically with just few degrees of temperature increase. As with humans, a sustained period of high metabolism leads to energy exhaustion; one early study found that snow crabs stop feeding altogether in temperatures above 53.6 degrees F). It is also likely that, when the Gulf of Alaska heated to unsustainable levels, groundfish like Pacific cod fled north to the Bering Sea, thus increasing predation pressure. Perhaps, Litzow says, warmer water intensifies the crabs’ vulnerability to diseases. Maybe it’s a mix of all these factors. “We know it’s really not the snow crab itself,” he says, “but the web of connections that make up the ecosystem it lives in.”

Since the Bering Sea’s snow crab fishery became St. Paul’s primary source of revenue in the 1980s, the city has learned to prepare for this creature’s boom-and-bust cycles by establishing an emergency fund. But in the past, says Cory Lescher, science advisor for Alaska Bering Sea Crabbers, a trade group, the community could rely on other fisheries, like king and bairdi crab and halibut, “to weather the storm and get them through the next couple of years.” These days, though, the kings are virtually gone; the bairdi are diminished to the point that quotas aren’t high enough to pay the bills; and the halibut have been in decline for the past decade. “The scale of this,” Lescher continues, “is something we’ve never seen.”

Snow crabs caught in a crab pot.

Danita Delimont / Alamy Stock Photo

In February, Zavadil had said that, in order not to completely exhaust its emergency fund. St. Paul was going to scale back on basic community services. It would need a volunteer ambulance driver and could no longer pay for a medical transport plane to fly in regularly from the mainland. But those cuts and others would hardly be enough. “We can only continue to dip into that for so long before it’s all gone,” Zavadil said. (St. Paul was approved for funding as part of an Alaska-wide federal disaster declaration in the wake of the snow crab collapse, but the community has not yet received its share of the money.)

While he said he was hopeful that the snow crab would return — an encouraging number of juveniles have been observed in recent survey trawls — Zavadil pointed out that “we’re working to plan for economic diversification.” The island’s small tourism industry is one hopeful alternative. St. Paul is a key stopover for rare migratory birds, and when we spoke in May, the first planeload of birders had landed a few days earlier. Some small cruise ships would arrive at the height of summer. The city had imposed a modest $12 wharf fee and was thinking about adding a tourism tax to rental cars. “That by far does not make up for any of the tax dollars we get from the crab fishery,” he said. “But it’s helpful.”

He described a recent “community open house,” at which members of the tribal government put big Post-it notes on the wall for residents to write down the things they liked about living in St. Paul and the things they felt were challenging about living there. Some of the biggest concerns were about the school. Would they be able to get and keep good teachers? Would the kids stick around after graduation or move away in search of work? Zavadil described his neighbors as hopeful yet worried.

“We’re doing our best just to try to make it through this,” he said, “and make sure that St. Paul’s still a place that people want to call home, can make a living, and have a sustainable economic future.”

Alaska

Interior Plans to Rescind Drilling Ban in Alaska’s National Petroleum Reserve

A critical question demands an actionable answer. To date, many takes on various sides of the debate have focused more on high-level narrative than precise policy prescriptions. If we zoom in to look at the actual sources of delay in clean energy projects, what sorts of solutions would we come up with? What would a data-backed agenda for clean energy abundance look like?

The most glaring threat to clean energy deployment is, of course, the Republican Party’s plan to gut the Inflation Reduction Act. But “abundance” proponents posit that Democrats have imposed their own hurdles, in the form of well-intentioned policies that get in the way of government-backed building projects. According to some broad-brush recommendations, Democrats should adopt an abundance agenda focused on rolling back such policies.

But the reality for clean energy is more nuanced. At least as often, expediting clean energy projects will require more, not less, government intervention. So too will the task of ensuring those projects benefit workers and communities.

To craft a grounded agenda for clean energy abundance, we can start by taking stock of successes and gaps in implementing the IRA. The law’s core strategy was to unite climate, jobs, and justice goals. The IRA aims to use incentives to channel a wave of clean energy investments towards good union jobs and communities that have endured decades of divestment.

Klein and Thompson are wary that such “everything bagel” strategies try to do too much. Other “abundance” advocates explicitly support sidelining the IRA’s labor objectives to expedite clean energy buildout.

But here’s the thing about everything bagels: They taste good.

They taste good because they combine ingredients that go well together. The question — whether for bagels or policies — is, are we using congruent ingredients?

The data suggests that clean energy growth, union jobs, and equitable investments — like garlic, onion, and sesame seeds — can indeed pair well together. While we have a long way to go, early indicators show significant post-IRA progress on all three fronts: a nearly 100-gigawatt boom in clean energy installations, an historic high in clean energy union density, and outsized clean investments flowing to fossil fuel communities. If we can design policy to yield such a win-win-win, why would we choose otherwise?

Klein and Thompson are of course right that to realize the potential of the IRA, we must reduce the long lag time in building clean energy projects. That lag time does not stem from incentives for clean energy companies to provide quality jobs, negotiate Community Benefits Agreements, or invest in low-income communities. Such incentives did not deter clean energy companies from applying for IRA funding in droves. Programs that included all such incentives were typically oversubscribed, with companies applying for up to 10 times the amount of available funding.

If labor and equity incentives are not holding up clean energy deployment, what is? And what are the remedies?

Some of the biggest delays point not to an excess of policymaking — the concern of many “abundance” proponents — but an absence. Such gaps call for more market-shaping policies to expedite the clean energy transition.

Take, for example, the years-long queues for clean energy projects to connect to the electrical grid, which developers rank as one of the largest sources of delay. That wait stems from a piecemeal approach to transmission buildout — the result not of overregulation by progressive lawmakers, but rather the opposite: a hands-off mode of governance that has created vast inefficiencies. For years, grid operators have built transmission lines not according to a strategic plan, but in response to the requests of individual projects to connect to the grid. This reactive, haphazard approach requires a laborious battery of studies to determine the incremental transmission upgrades (and the associated costs) needed to connect each project. As a result, project developers face high cost uncertainty and a nearly five-year median wait time to finish the process, contributing to the withdrawal of about three of every four proposed projects.

The solution, according to clean energy developers, buyers, and analysts alike, is to fill the regulatory void that has enabled such a fragmentary system. Transmission experts have called for rules that require grid operators to proactively plan new transmission lines in anticipation of new clean energy generation and then charge a preestablished fee for projects to connect, yielding more strategic grid expansion, greater cost certainty for developers, fewer studies, and reduced wait times to connect to the grid. Last year, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission took a step in this direction by requiring grid operators to adopt regional transmission planning. Many energy analysts applauded the move and highlighted the need for additional policies to expedite transmission buildout.

Another source of delay that underscores policy gaps is the 137-week lag time to obtain a large power transformer, due to supply chain shortages. The United States imports four of every five large power transformers used on our electric grid. Amid the post-pandemic snarling of global supply chains, such high import dependency has created another bottleneck for building out the new transmission lines that clean energy projects demand. To stimulate domestic transformer production, the National Infrastructure Advisory Council — including representatives from major utilities — has proposed that the federal government establish new transformer manufacturing investments and create a public stockpiling system that stabilizes demand. That is, a clean energy abundance agenda also requires new industrial policies.

While such clean energy delays call for additional policymaking, “abundance” advocates are correct that other delays call for ending problematic policies. Rising local restrictions on clean energy development, for example, pose a major hurdle. However, the map of those restrictions, as tracked in an authoritative Columbia University report, does not support the notion that they stem primarily from Democrats’ penchant for overregulation. Of the 11 states with more than 10 such restrictions, six are red, three are purple, and two are blue — New York and Texas, Virginia and Kansas, Maine and Indiana, etc. To take on such restrictions, we shouldn’t let concern with progressive wish lists eclipse a focused challenge to old-fashioned, transpartisan NIMBYism.

“Abundance” proponents also focus their ire on permitting processes like those required by the National Environmental Policy Act, which the Supreme Court curtailed last week. Permitting needs mending, but with a chisel, not a Musk-esque chainsaw. The Biden administration produced a chisel last year: a NEPA reform to expedite clean energy projectsand support environmental justice. In February, the Trump administration tossed out that reform and nearly five decades of NEPA rules without offering a replacement — a chainsaw maneuver that has created more, not less, uncertainty for project developers. When the wreckage of this administration ends, we’ll need to fill the void with targeted permitting policies that streamline clean energy while protecting communities.

Finally, a clean energy abundance agenda should also welcome pro-worker, pro-equity incentives like those in the IRA “everything bagel.” Despite claims to the contrary, such policies can help to overcome additional sources of delay and facilitatebuildout.

For example, Community Benefits Agreements, which IRA programs encouraged, offer a distinct, pro-building advantage: a way to avoid the community opposition that has become a top-tier reason for delays and cancellations of wind and solar projects. CBAs give community and labor groups a tool to secure locally-defined economic, health, and environmental benefits from clean energy projects. For clean energy firms, they offer an opportunity to obtain explicit project support from community organizations. Three out of four wind and solar developers agree that increased community engagement reduces project cancellations, and more than 80% see it as at least somewhat “feasible” to offer benefits via CBAs. Indeed, developers and communities are increasingly using CBAs, from a wind farm off the coast of Rhode Island to a solar park in California’s central valley, to deliver tangible benefits and completed projects — the ingredients of abundance.

A similar win-win can come from incentives for clean energy companies to pay construction workers decent wages, which the IRA included. Most peer-reviewed studies find that the impact of such standards on infrastructure construction costs is approximately zero. By contrast, wage standards can help to address a key constraint on clean energy buildout: companies’ struggle to recruit a skilled and stable workforce in a tight labor market. More than 80% of solar firms, for example, report difficulties in finding qualified workers. Wage standards offer a proven solution, helping companies attract and retain the workforce needed for on-time project completion.

In addition to labor standards and support for CBAs, a clean energy abundance agenda also should expand on the IRA’s incentives to invest in low-income communities. Such policies spur clean energy deployment in neighborhoods the market would otherwise deem unprofitable. Indeed, since enactment of the IRA, 75% of announced clean energy investments have been in low-income counties. That buildout is a deliberate outcome of the “everything bagel” approach. If we want clean energy abundance for all, not just the wealthy, we need to wield — not withdraw — such incentives.

Crafting an agenda for clean energy abundance requires precision, not abstraction. We need to add industrial policies that offer a foundation for clean energy growth. We need to end parochial policies that deter buildout on behalf of private interests. And we need to build on labor and equity policies that enable workers and communities to reap material rewards from clean energy expansion. Differentiating between those needs will be essential for Democrats to build a clean energy plan that actually delivers abundance.

Alaska

Trump Administration Proposal Would Lift Biden-Era Limits on Alaska Oil Drilling

Alaska

3 Trump officials meet with resource industry leaders in Anchorage to launch Alaska energy trip

Alaska’s governor, its two U.S. senators and three Trump administration officials gathered Sunday in an Anchorage hotel to extol an executive order meant to boost the state’s resource development industry.

The order at the heart of the meeting was signed by President Donald Trump in January, during the first day of his second term. It laid out several provisions aimed at smoothing the path toward more drilling for oil and gas; more logging; more mining; and more hunting on federal lands.

In attendance in a cramped ballroom at downtown Anchorage’s Hotel Captain Cook were Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, Energy Secretary Chris Wright, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin, U.S. Sens. Dan Sullivan and Lisa Murkowski and Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy. Alongside them were several dozen invited resource development industry leaders, state lawmakers and Dunleavy administration officials who were in a jovial mood as they spoke about the potential of Alaska’s resource industry under Trump’s leadership.

Sullivan, whose office organized the event, called the visit by Trump administration officials “a seminal event.” He referred to Burgum as “Alaska’s landlord.”

The roundtable was the first of numerous events that the Trump officials planned to attend during a multiday visit to Alaska. Burgum, Wright and Zeldin were expected to travel to the North Slope early in the week to meet with residents and oil field workers. They were also scheduled to participate in a sustainable energy conference organized by Dunleavy in Anchorage.

Sunday’s two-hour roundtable was not open to the press. But after its conclusion, journalists were ushered in to listen to closing remarks by participants.

“There’s a lot of alignment amongst Alaskans behind this executive order,” said Rebecca Logan, chief executive of the Alaska Support Industry Alliance.

Sullivan began his remarks by pulling out a pamphlet his office had designed when former President Joe Biden was in office, which listed several executive decisions taken by the Biden administration that Sullivan has said were meant to “lock up” Alaska. Sullivan proceeded to rip up the pamphlet and throw the pieces in the air.

“We got a new sheriff in town,” he said.

Sullivan said the meeting was meant to facilitate the fast implementation of Trump’s January executive order, which as of yet has not led to the realization of new resource development in the state.

“We have the need for speed,” said Sullivan.

Murkowski, a Republican who has spoken frequently against actions and priorities articulated by the Trump administration, thanked the Trump officials for their “unique” visit to the state but left the event before the roundtable concluded.

“To have them here in our state, to be listening to industry leaders, to be listening to Alaskans — this is a newsworthy takeaway,” said Murkowski. ”It is instructive, I think, for those of us here in Alaska to realize the partnership that we have with this administration. The Trump administration has looked at Alaska’s potential as an asset, instead of a liability.”

The comments offered by meeting attendees were replete with grand statements but sparse on details.

Both Sullivan and Murkowski said they emerged from the meeting with a renewed interest in permitting reform that would make it easier for private industry to launch new resource development projects in the state.

“It shouldn’t take 20 years to permit an old mine in Alaska. That hurts people, when you delay things for so long,” said Sullivan. “The radical far left groups that do it, they don’t care about our state, they don’t care about the communities, like in Western Alaska, with their poverty that they have. They just want to shut down everything.”

“We just need the federal government to help us, and this is the team that wants to do it,” said Sullivan.

Zeldin, the EPA administrator, said “there is nowhere more important for the three of us to be right now than right here,” referring to himself, Wright and Burgum.

“I am extraordinarily confident in knowing that once this very productive visit to Alaska is done and we head back to Washington, D.C., that this team is able to work with your governor, with your congressional delegation, to be able to work with all of you to make sure this wasn’t just some ideal on a Sunday morning of an amazing future ahead for Alaska. It’s not just a dream,” said Zeldin.

Wright, the energy secretary, said that Trump got elected on the promise to deliver “not handouts to Alaskans” — rather, “freedom to develop the underground materials and turn them into resources.”

Interior Secretary Burgum said, “Alaska has an opportunity to allow us to do one of the mandates of the Trump administration, which is to sell energy to our friends and allies, so they don’t have to buy it from our adversaries.”

“The potential of this state is unbelievable,” said Burgum. “It can really become a powerhouse of a state.”

“But we’ve got to get the federal government out of your way. That’s what the three of us are here to do” said Burgum.

LNG discussion

Chief among the resource development priorities emphasized by Trump during the first months of his second term has been a liquefied natural gas pipeline project that has been long sought by Alaska politicians. For decades, the project has remained far from realization, in large part because it is expected to cost a staggering $44 billion.

Sullivan acknowledged Sunday that “we get Alaskans who roll their eyes” at the LNG project, but he said there has been “really historic progress happening” both with interest from the private sector and with Trump’s stated commitment to the project.

“A lot of tailwinds there, exciting times. We’re not there yet, but it’s exciting,” said Sullivan.

The high-level meeting offered no new details on developments with the project.

Dunleavy recently went on a multi-stop trip to Asian countries to promote Alaska’s LNG. Burgum said Sunday that “there are huge implications for national security for the United States to be able to export energy to our Pacific allies — South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Taiwan.”

“We just have to be able to do math in this country and understand that the impacts are so low,” said Burgum.

Sullivan said that the Trump administration would “work with us on federal loan guarantees for the Alaska LNG project,” but the officials in attendance did not offer new details on how the project would be financed.

“The Alaska pipeline, if we get off-take agreements, if we sell energy to our Pacific allies, there will be people lined up to finance it,” said Burgum. “It won’t take foreign capital to build the pipeline. There may be foreign interest in wanting to be part of it, because it’s going to be a great project, but what we really need is customers.”

Renewable energy

Even as the Trump administration has championed Alaska’s energy potential, it has taken steps that could thwart several ongoing renewable energy projects throughout the state.

Alaska utilities in recent years have been turning increasingly to renewables as costs for fossil-fuel electricity have increased. Those projects were enabled in part through tax credits approved in Biden-era legislation. Now, the Trump administration is freezing grants for some energy projects, and with the passage of the latest tax and spending bill, Republicans in Congress are looking to undo those tax credits — with support from Alaska’s U.S. Rep. Nick Begich.

That could mean that several projects with the potential of lowering Alaskans’ energy bills will be halted.

Those impacts were not on the agenda for the public portion of Sunday’s meeting.

Murkowski is one of four Senate Republicans who have spoken in favor of preserving the tax credits that have paved the way for renewable energy projects in Alaska.

Asked Sunday about the Trump administration’s impacts on Alaska’s renewable energy projects, Sullivan was noncommittal.

“We’re an all-of-the-above energy state,” Sullivan said Sunday. “We’re looking at the different elements of what’s in the House budget reconciliation bill … but we’re still studying the bill and trying to figure out what’s the best way to balance what’s in the budget reconciliation with the overall goals of that bill.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoPlastic Spoons, Umbrellas, Violins: A Guide to What Americans Buy From China

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMOVIE REVIEW – Mission: Impossible 8 has Tom Cruise facing his final reckoning

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘Magellan’ Review: Gael Garcia Bernal Plays the Famous Explorer in Lav Diaz’s Exquisitely Shot Challenge of an Arthouse Epic

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThe oldest Fire TV devices are losing Netflix support soon

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoMaryland, Cornell to face off in NCAA men’s lacrosse championship game

-

Tennessee1 week ago

Tennessee1 week agoTennessee ace Karlyn Pickens breaks her own record for fastest softball pitch ever thrown

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPower outage disrupts final day of Cannes Film Festival, police investigate possible arson

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump talks with Putin, spars with South African leader, threatens EU tariff hike in 18th week in office