Sports

Column: Baseball legend Willie Mays instrumental in California fight against housing discrimination

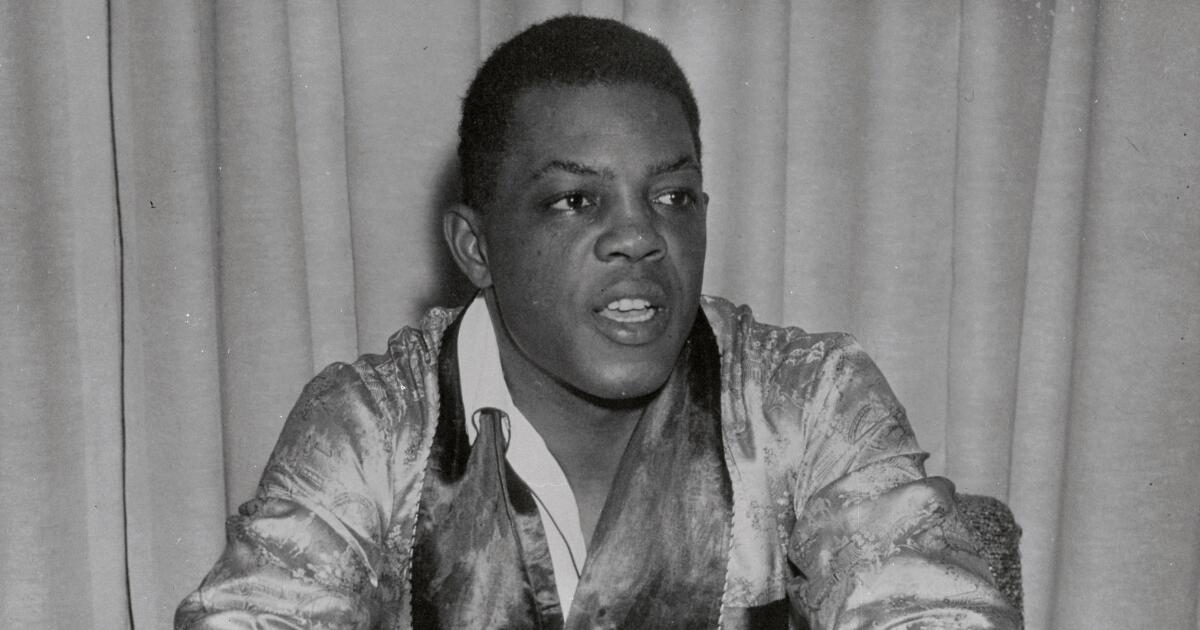

As a ballplayer, Willie Mays was arguably the greatest of all time — baseball’s GOAT. But he also starred in another endeavor — as an important California civil rights pioneer.

Mays never wanted to be an activist about anything off the baseball diamond. But the racism he encountered after moving to San Francisco stirred others to leap to his cause and ultimately helped motivate the city and state governments to outlaw housing discrimination.

His role began when Mays arrived in San Francisco from New York with the Giants baseball team in late 1957. Local folks in supposedly enlightened San Francisco welcomed the star outfielder by trying to bar him from a white neighborhood.

Mays downplayed it publicly, but his wife, Marghuerite Mays, spoke out to reporters: “Down in Alabama where we come from, you know your place. But up here, it’s all a lot of camouflage. They grin in your face and deceive you.”

Willie Mays receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama at the White House in 2015.

(Evan Vucci / Associated Press)

Never mind that Mays was en route to the baseball Hall of Fame as the best all-around ballplayer in history. Didn’t matter. If a Black man was allowed to buy a home in a desirable neighborhood — adjoining tony St. Francis Wood in the Sunset District — nearby property values would tumble. At least that’s what white neighbors openly feared.

“I happen to have a few pieces of property in the area, and I stand to lose a lot if colored people move in,” a nearby home builder told reporters.

Yes, that was San Francisco — in fact, virtually all of California — until laws were passed in the 1960s to stop such discrimination. The change was aided significantly by Mays’ indirect help, according to another legendary Willie from San Francisco — former mayor and longtime state Assembly Speaker Willie Brown.

I called Brown, 90, after Mays died this week at age 93. Brown, a rare Black lawyer in late 1950s San Francisco, struck up an early friendship with Mays.

“He was a joy, frankly. A fun guy,” Brown says.

Brown credits the racial bias against Mays with galvanizing the city into adopting an ordinance forbidding housing discrimination.

“It started with Willie Mays,” Brown told me. “As a result of his being rejected, newspapers suddenly became aware of the racism in San Francisco.

“San Francisco wasn’t racist like other parts of the country. People smiled.”

Brown continued: “The fair housing law of San Francisco was passed because Mays got denied the right of housing. That escalated the need to change. He was the most dramatic example of how discrimination was practiced on people of color.”

In 1963, spurred by Gov. Pat Brown and Bay Area lawmakers, the state Legislature passed a bill outlawing racial discrimination in the sale and rental of housing. It needed all the support it could muster and generated the biggest, bitterest political brawl I’ve ever witnessed in Sacramento.

California voters overwhelmingly repealed the law the next year. But the repeal was declared unconstitutional by both the state and U.S. supreme courts.

Mays didn’t participate personally in that fight, but Brown certainly did.

A transplant from Jim Crow east Texas, Brown became a civil rights activist in San Francisco about the time Mays was arriving from New York. In fact, Brown was persistently snubbed by real estate agents when he tried to buy a house in 1961. He responded by leading a sit-in at a Realtor’s office.

The Mays incident occurred after he offered the asking price of $37,500 for a three-bedroom home in an upscale, tree-lined, all-white neighborhood. After he waited several days, his offer was turned down. The house remained on the market for the same price — but unavailable for the star ballplayer.

The San Francisco Chronicle got wind of the rejection and ran this banner at the top of Page 1: “WILLIE MAYS IS DENIED S.F. HOUSE–RACE ISSUE.” The headline on the story read: “Willie Mays is Refused S.F. House–Negro.”

“I didn’t figure I would have this much trouble trying to buy a place,” Mays told a TV reporter. “When I go looking for a house, I don’t worry about who’s living beside me.”

Unlike nervous white people of that era.

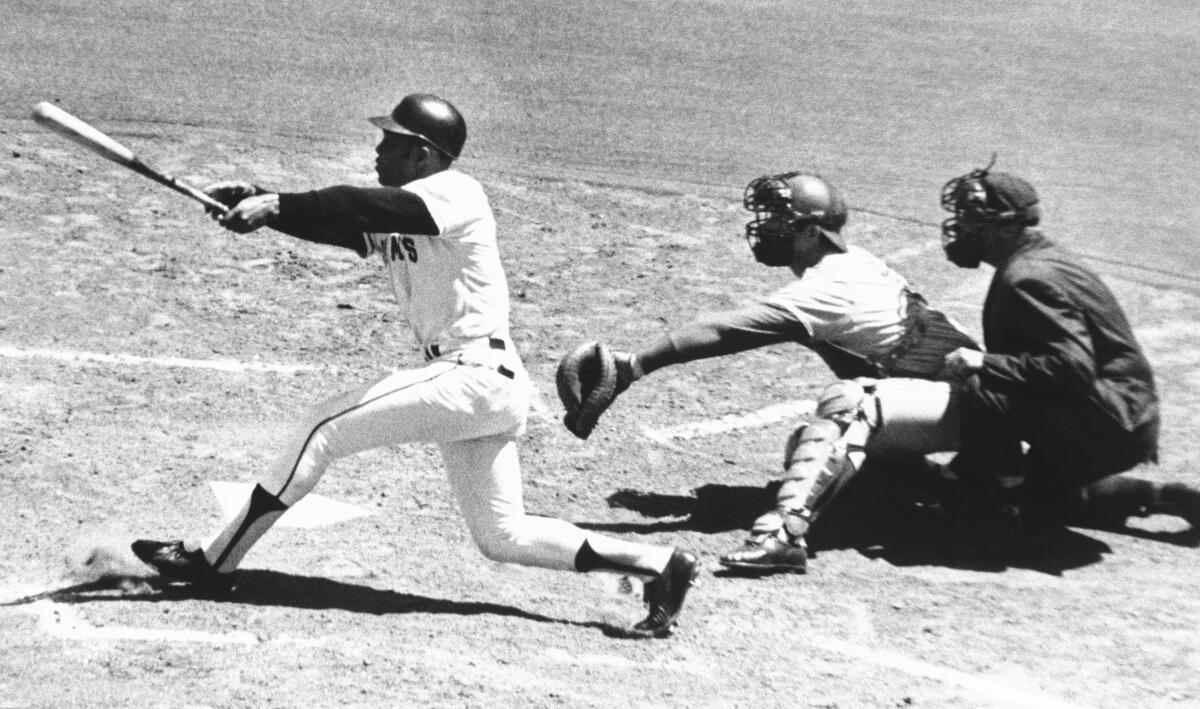

Mays gets the 3,000th hit of his career, a single to left, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco in 1970.

(Robert H. Houston / Associated Press)

San Francisco Mayor George Christopher — a moderate Republican, back when such a breed existed — offered to let Mays and his wife live temporarily at his home.

Ultimately, the homeowner backed down, despite being berated by neighbors. Mays moved in. And almost immediately someone threw a brick through a window.

Mays kept his mind on baseball and eventually became the pride of San Francisco.

As a bottom-tier sportswriter for United Press International, I was privileged to watch lots of Giants games at windy Candlestick Park in the early 1960s.

Mays’ statistics are phenomenal: a .301 career batting average, 660 home runs, 3,293 hits, 339 stolen bases, 12 Gold Glove awards in center field, 24 All-Star games.

In the 1961 All-Star Game at Candlestick that I helped cover, Mays doubled home the tying run in the 10th inning and then scored the winning run on a single by Pittsburgh’s Roberto Clemente as the National League edged the American League, 5-4.

But box scores and stats tell only part of the story of Mays’ greatness.

What I remember most about him was his playing with elation and exuberance — galloping around first base, always a threat to stretch a single into a double and a menace to steal second in any case. Full speed no matter the score. Cap flying.

In his long post-career, Mays provided a comfortable nostalgic link back to baseball’s exciting heyday — before blah analytics and emphasis on astronomical free agent salaries.

America can’t afford to lose such people. He didn’t hate. He brought cheer.

And — while there’s no stats on it — he assisted in beating housing discrimination.

Sports

Damien basketball team opens 24-0 lead, then holds off Etiwanda

Junior guard Zaire Rasshan of Damien knows football. His father, Osaar, was a backup quarterback at UCLA from 2005-09. Rasshan played quarterback his freshman season at Damien until deciding basketball was his No. 1 sport.

So when Rasshan looked up at the scoreboard Thursday night at Etiwanda in the first quarter and saw the Spartans had scored the first 24 points, he had to think football.

“That was crazy,” he said. “That’s three touchdowns and a field goal.”

Damien (17-4, 2-0) was able to hold off Etiwanda 56-43 to pick up a key Baseline League road victory. Winning at Etiwanda has been a rarity for many teams through the years. But Damien’s fast start couldn’t have been any better. The Spartans didn’t miss any shots while playing good defense for their 24-0 surge. Etiwanda’s first basket didn’t come until the 1:38 mark of the first quarter.

“When we play together, we can beat anyone,” Rasshan said.

Rasshan was a big part of the victory, contributing 23 points. Eli Garner had 14 points and 11 rebounds.

Etiwanda came in 18-1 and 1-0 in league. The Eagles missed 13 free throws, which prevented any comeback. The closest they got in the second half was within 11 points.

Damien’s victory puts it squarely in contention for a Southern Section Open Division playoff spot. The Spartans lost in the final seconds to Redondo Union in the Classic at Damien, showing they can compete with the big boys in coach Mike LeDuc’s 52nd season of coaching.

Rasshan is averaging nearly 20 points a game. He made three threes. And he hasn’t forgotten how to make a long pass, whether it’s with a football or basketball.

Sports

Ole Miss staffer references Aaron Hernandez while discussing ‘chaotic’ coaching complications with LSU

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

The chaos between LSU coaches who left Ole Miss alongside Lane Kiffin but are still coaching the Rebels in the College Football Playoff is certainly a whirlwind.

Joe Judge, Ole Miss’ quarterbacks coach, has found himself in the thick of the drama — while he is not headed for Baton Rouge, he’s had to wonder who he will be working with on a weekly basis.

When asked this week about what it’s like to go through all the trials and tribulations, Judge turned heads with his answer that evoked his New England Patriots days.

Aaron Hernandez sits in the courtroom of the Attleboro District Court during his hearing. Former New England Patriot Aaron Hernandez has been indicted on a first-degree murder charge in the death of Odin Lloyd in North Attleboro, Massachusetts, on Aug. 22, 2013. (Jared Wickerham/Getty Images)

“My next-door neighbor was Aaron Hernandez,” Judge said, according to CBS Sports. “I know this is still more chaotic.”

Hernandez was found guilty of the 2013 murder of Odin Lloyd, which occurred just three years into his NFL career.

“If you watch those documentaries, my house is on the TV next door,” Judge added. “The detectives knocked on my door to find out where he was. I didn’t know. We just kind of talked to the organization. But it was obviously chaotic.”

Aaron Hernandez was convicted of the 2013 murder of semipro football player Odin Lloyd. (REUTERS/Brian Snyder)

FROM MR IRRELEVANT TO GENERATIONAL WEALTH, BROCK PURDY WANTS TO USE HIS LIFESTYLE FOR GOOD

Judge, though, was able to compare the two situations to see how players can combat wild distractions.

“Those players that year handled that extremely well. Came out of that chaos, and we had some really good direction inside with some veterans and some different guys. You have something like that happen — how do you handle something like that? How do you deal with something like that? So you keep the focus on what you can handle, what you can control, which at that time was football for us, and we went through the stretch, and we were able to have success that year,” Judge said.

Judge also compared this scenario to the 2020 NFL season when he was head coach of the New York Giants, saying he would have “no idea” who would be available due to surprise positive COVID-19 tests.

Head coach Joe Judge of the New York Giants looks on during the second quarter against the Dallas Cowboys at MetLife Stadium. The game took place in East Rutherford, New Jersey, on Dec. 19, 2021. (Sarah Stier/Getty Images)

The Rebels face Miami in the Fiesta Bowl, the College Football Playoff Semifinal, on Thursday night.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X, and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.

Sports

Prep talk: Calabasas basketball team is surging with 11 wins in last 12 games

Calabasas pulled off a huge win in high school basketball on Tuesday night, handing Thousand Oaks its first defeat after 16 victories in a Marmonte League opener.

The Coyotes (13-5) have quietly turned around their season after a 2-4 start, winning 11 of their last 12 games.

One of the major contributors has been 6-foot-3 junior guard Johnny Thyfault, who’s averaging 16 points and has become a fan favorite because of his dunking skills. He also leads the team in taking charging fouls.

He transferred to Calabasas after his freshman year at Viewpoint.

As for beating Thousand Oaks, coach Jon Palarz said, “We got to play them at home and had great effort.”

This is a daily look at the positive happenings in high school sports. To submit any news, please email eric.sondheimer@latimes.com.

-

Detroit, MI5 days ago

Detroit, MI5 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX4 days ago

Dallas, TX4 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Nebraska2 days ago

Nebraska2 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Iowa2 days ago

Iowa2 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Nebraska2 days ago

Nebraska2 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoSpotify digs in on podcasts with new Hollywood studios