Sports

After being ‘blindsided’ by Braves, Freddie Freeman happy to be back home with Dodgers

For many of his first day as a Dodger, a smile was planted on Freddie Freeman’s face.

Recent off finalizing his six-year, $162 million contract with the staff, Freeman arrived to the staff’s spring coaching advanced Friday early within the morning, sporting a dapper black swimsuit and a glove as he walked into the power.

He placed on Dodger blue for the primary time within the afternoon, taking the sphere in staff athletic put on for a exercise to a refrain of cheers from a whole lot of followers.

Then, throughout an introductory press convention overlooking the stadium at Camelback Ranch, Freeman slipped into his new uniform, exhibiting off the newly sewn No. 5 displayed throughout the again.

“I simply needed to get right here and get going,” Freeman mentioned. “Everybody simply welcomed me with open arms.”

The one time Freeman’s expression modified Friday was when the topic of his previous staff got here up. The previous MVP, in spite of everything, as soon as anticipated to spend his total profession with the Atlanta Braves. And simply days faraway from his official goodbye to the membership, he was nonetheless struggling to make sense of the separation.

“I believed I used to be going to spend my complete profession there,” he mentioned. “However finally generally plans change, and plans did change.”

Freeman’s doubts about returning to the Braves slowly set in through the previous 12 months.

He mentioned the Braves made one formal provide for a contract extension final season on the commerce deadline, then by no means responded to a counterproposal from his representatives.

He mentioned that whereas the Dodgers wooed him closely from the beginning of the offseason, Braves officers solely referred to as him twice, as soon as earlier than the lockout and as soon as after merely to test in.

And he mentioned that, when the Braves traded for Oakland A’s first baseman Matt Olson on Monday — successfully ending Freeman’s time in Atlanta — he had no concept the information was coming.

“To be trustworthy, I used to be blindsided,” mentioned Freeman, who to that time nonetheless believed a return to Atlanta was doable. “I believe each emotion got here throughout. I used to be harm. It’s actually exhausting to place into phrases nonetheless.”

Freeman was additionally requested if he noticed Braves common supervisor Alex Anthopoulos tearing up whereas introducing Olson this week.

“I noticed ‘em,” Freeman mentioned. “Yup. That’s all I’ll say.”

Freeman’s cope with the Dodgers got here collectively quickly after, with Freeman agreeing to contract — which incorporates roughly $57 million of deferred cash to be paid out between 2028 and 2040, in response to an individual with data of the state of affairs not licensed to debate it publicly — on Wednesday, passing a bodily in Los Angeles on Thursday, then jetting out to Arizona to hitch the staff Friday.

“The final week has been somewhat little bit of a whirlwind,” Freeman mentioned. “However I wouldn’t need to be anyplace else proper now.”

Dodgers first baseman Freddie Freeman laughs as he places on a Dodgers jersey subsequent to Andrew Friedman, the Dodgers’ president of baseball operations.

(Charlie Riedel / Related Press)

Freeman mentioned the prospect to return to Southern California — he’s an Orange County native and his father and grandpa nonetheless dwell within the space — performed a significant component in his choice. He was additionally drawn in by the Dodgers’ pitch, which included Zoom calls with president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman and supervisor Dave Roberts.

“I believe everybody knew the state of affairs I used to be in and so they have been very upfront and so they cared about the place I used to be coming from and the way lengthy I used to be there,” Freeman mentioned. “They cared about household. I expressed household and profitable. That’s all I care about and that’s what they care about, too.”

Third baseman Justin Turner aided within the pursuit, too.

“His identify popped up on my cellphone fairly a bit all through this complete course of,” Freeman mentioned, laughing.

Added Friedman: “Over time, each time Justin Turner received to first base, he’d have somewhat phrase with him about how good he’d look in Dodger blue”

For Friedman, going after Freeman was a no brainer.

The five-time All-Star has established himself as among the best hitters in baseball over the past decade. He crammed a gap within the Dodgers’ in any other case loaded lineup, giving them one other left-handed slugger to interchange Corey Seager. The staff had simply seen first-hand how tough Freeman is to play towards, too, having misplaced to the Braves in a six-game NL Championship Collection.

“I believe what he does on the sphere is clear to everybody,” Friedman mentioned. “We’ve competed towards them three of the final 4 years within the playoffs and the stress, [even in] the innings earlier than he comes up, the lineup type of orbits round him.”

Now, it’s the Dodgers who will profit, their roster bolstered once more by the arrival of one other one in all baseball’s greatest stars.

“If I used to be going to depart the place I used to be for 15 years,” Freeman mentioned, “coming house and being with this group might be the very best factor.”

Sports

Andy Murray: The benevolent thorn in the side that tennis badly needed

For more stories on Wimbledon, click here to have them added to your feed.

A hundred years from now, a tennis nerd will ask the floating hologram next to his ear about the great male players from the early part of the 21st century.

The hologram will wax poetic about a triumvirate of players known as the Big Three: Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, and Rafael Nadal. They ruled the sport before the advent of nuclear-powered strings and 200 miles per hour serves, winning around 70 Grand Slam titles between them.

Then, almost as an afterthought, it will mention a couple of others who won a few of Earth’s most important tournaments, before the tours expanded to include the exoplanets of Alpha Centauri.

“Stan Wawrinka and Andy Murray won three Grand Slams each and were the next best of the era of The Big Three,” the hologram will say.

Humans of 2124: do not trust your holograms, especially if they mention that in his final Wimbledon competition, likely the penultimate tournament of his career, he had to endure a 21-year-old deciding to blow off a mixed doubles match with him at the last minute. Emma Raducanu, his compatriot who is reviving her nascent career with a run into the second week at Wimbledon, withdrew in order to prioritise her singles chances in an open draw, over a chance to be on court with Murray, her idol, for what figured to be his final match on the Wimbledon grass.

Andy Murray spent his career defying expectations under the pressure of living up to them. (Mike Hewitt / Getty Images)

So other than a planned doubles effort at the Olympics, this really is it for Wimbledon, allowing the efforts to secure his proper spot in the tennis lexicon to begin. No disrespect to Wawrinka, an excellent player with a fine career, but Murray didn’t spend the past three decades bucking convention, being the ultimate thorn in the side of so many assumptions about tennis, to have holograms and the tennis nerds that employ them remember him in the same sentence.

Maybe this is what kept Murray going the past year and a half, desperate for one more run to the business end of the grandest events in the sport long after pretty much everyone could see that wasn’t in the stars. Maybe this is why he hobbled onto courts to take on the best players in the world when climbing stairs was becoming a struggle.

In March, Murray stood in a hotel gym with Brad Gilbert, the former pro and longtime coach, in Indian Wells, California, late at 4 am. An early rising insomniac and a jet-lagged Scot jabbering about new racket technology, Murray telling Gilbert that he might have found a new stick that could give him a little extra… something.

Something that could prove that he still had the magic.

Maybe Murray really was sticking around simply because he loved just about everything about his job — the feel of the racket in his hands, the life of a globetrotting superstar, the incomparable highs that the heat of competitions produced. He burned with jealousy watching players like Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz as they started out on their journeys. He would have gone back to the beginning if he could have, not to change anything necessarily, but just because he would have loved to do it all again.

“I want to play tennis because I, you know, I do enjoy this,” he said last year in Surbiton, where he was playing a Challenger event instead of the French Open to get extra time on the grass ahead of Wimbledon.

“I love it. It’s not like this is like a massive chore for me.”

Murray and his new Yonex racket in Geneva, earlier in 2024. (Fabrice Coffrini / AFP via Getty Images)

It never really was, even if that’s the way it looked as he growled his way through 1,000 matches. But it was also the joy of playing a game he loved, and proving just about every assumption about him and his sport wrong.

First there was the idea that a Scot could even be any good at junior level tennis. Golf maybe, but not tennis. Too many talented kids from friendlier tennis climates and locales to contend with. There weren’t many indoor courts, and not too many expert coaches other than his mother, Judy, and surely not enough top-tier competition to help him develop, other than his older brother, Jamie.

Murray wasn’t about to let that get in his way, whether that meant training harder during those first formative years or taking the radical step that few of his peers took.

“My mum did her best to create an environment for not just us two, but the players that were of a sort of performance level, and to get us together as much as we could because she understood how difficult it was,” Jamie Murray said during an interview last year.

“Obviously, Andy left when he was 15 — he went to Spain, he made the decision: ‘I really want to be a tennis player and to do that, I need to go to Spain to train’ and he was obviously very headstrong in that and he went. I stayed at home.”

Habits form early in tennis. In most cases, a 25-year-old’s forehand won’t look all that different from his 15-year-old version. Same goes for attitudes and approaches, like Murray’s penchant for bucking conventional wisdom.

So Andy, nice junior career, but surely you won’t be able to win much against Federer and Nadal, or even your buddy from juniors, Djokovic. Born at the wrong time. Tough luck.

He beat Nadal seven times and Federer and Djokovic 11.

Murray and his buddy from Serbia playing doubles together at the 2006 Australian Open. (Clive Brunskill / Getty Images)

OK Andy, nice that you can get the occasional win against top players, but a British man hasn’t won a Grand Slam in nearly a century. Can’t happen.

And then he won the U.S. Open in 2012 and Wimbledon in 2013 and 2016, despite more pressure than any player of the modern era has likely ever felt on Centre Court.

And don’t forget about the losses, including five Australian Open finals, only to either Djokovic or Federer, like so many of his losses in the finals or semifinals of big tournaments.

“I’m playing against guys that are winning these tournaments like 12 times each year in their careers,” he recalled during an interview last year.

And yet he still won 46 tournaments, including 14 Masters 1000 titles, the level just below a Grand Slam, far more than any player of his era other than the Big Three. Not to pick on Wawrinka, but he won 16 titles, just one a Masters 1000.

Nice, Andy, but the No 1 taking in this era is out of reach.

He got there in 2016, when Nadal and Djokovic were still in their prime and Federer still had another three years of winning Grand Slams and making finals.

It didn’t come easy.

GO DEEPER

Fifty Shades of Andy Murray

“I basically just did everything, you know,” he recalled. “I would be on the running track. I’d be in the gym, lifting weights, I’d be doing core sessions, I’d be doing hot yoga, I’d be doing sprint work, speed work, just chucking everything at myself.”

He paid a price for that, putting so much stress on his hip that he had to undergo resurfacing surgery in 2019. Doctors told him he’d be lucky to be able to hit tennis balls with his children one day. He turned those words into a challenge to prove them as wrong as he possibly could, rising to 36th in the world last summer.

He relished being a kind of guinea pig, one of the first top athletes to test the limits of a hip made largely of metal.

Murray’s hip first derailed him, then became one of the symbols of his career. (Ashley Western / CameraSport via Getty Images)

“No one really knows where that limit is,” he said.

“I want to see what that is.”

All of that, though, was just the competitive contrarian in him, which extended to his off-court empathy for subjects and people that the sport can relegate or try to avoid.

Male tennis players have never shown all that much respect for the women’s game. Murray talked it up and hired a female coach, Amelie Mauresmo.

They also rarely speak ill of their fellow players, or support any action that might cause much discomfort to one of them. Murray was among the first to criticize the ATP Tour for dragging its feet for months before announcing it would investigate domestic abuse allegations against Alexander Zverev. The German settled a case involving charges brought by his ex-girlfriend and the mother of his child out of court, during the French Open.

Murray bought a condo in Miami and studied the training and business habits of NBA players to see what he could learn from them. When he didn’t like how management companies treated athletes, he opened his own shop. He bought an old deteriorating hotel in Scotland where his family had celebrated weddings and other important moments, even though advisors told him it was a terrible idea. He and his wife, Kim, have turned it into a luxury destination. He collects art.

Murray joins Kim and his team at Wimbledon after winning it, finally, in 2013. (Clive Brunskill / Getty Images)

So, of course he was never going to leave the tennis court when everyone else started planning his retirement. Of course he was going to do it his way, trying to wring every last chance he may or may not have had for glory out of his body, and that new Yonex racket he tried earlier this year, which led him to Gilbert in Miami at 4 am.

He would not just acquiesce, even attempting to return from back surgery on a spinal cyst in time for one last singles match on Centre Court that he would likely lose. There is a reason Murray holds the record for coming back from two sets down, overcoming that deficit 11 times, that last one at the 2023 Australian Open, when he played for five hours and 45 minutes and beat Thanasi Kokkinakis 4-6, 6-7 (4), 7-6 (5), 6-3, 7-5 just after that magic time, 4 am.

After some 30 years of going about life and tennis that way, old habits die hard.

Murray knew the end would come eventually.

Taking on conventional wisdom is one thing. Beating time and ageing is an altogether different animal. Murray just had to give it his best fight, which was the easiest part of the hardest thing, because he’s never known any other way.

(Top photos: Joe Toth/AELTC Pool, Simon Bruty/Anychance / Getty Images; Design: Dan Goldfarb for The Athletic)

Sports

Bronny James struggles in NBA Summer League debut

Bronny James got the start in his first Summer League game, but that was just about the lone bright spot.

The son of the NBA all-time leading scorer LeBron James was taken by his father’s Los Angeles Lakers in last week’s NBA Draft with the 55th selection, which has been a heavily debated topic.

On one hand, it’s historic. Lebron and Bronny are the first father-son duo to be active players in the NBA.

Yet, talk of nepotism has been rampant since the team hired James’ podcast cohost, JJ Redick, as its head coach.

Los Angeles Lakers guard Bronny James Jr. (9) reacts after being called for a foul against the Sacramento Kings during the second quarter at Chase Center. (Kelley L Cox/USA Today Sports)

Bronny was on the court for the Lakers on Saturday in San Francisco against the Sacramento Kings for his Summer League debut in his first chance to show what he’s got.

James scored just four points in the contest on 2-for-9 shooting, while grabbing two rebounds and handing out two assists. He also was a minus-16 on the floor, and the Kings took home a 108-94 win.

In his first press conference as a Laker, Bronny said he didn’t get “that much of an opportunity” to “showcase what I can really do” in his lone season at USC, where he averaged less than five points per game.

Los Angeles Lakers guard Bronny James Jr. scores a basket against the Sacramento Kings during the second quarter at Chase Center. (Kelley L Cox/USA Today Sports)

NBA PLAYER EJECTED FROM OLYMPICS TUNEUP AFTER PLACING HANDS AROUND FELLOW PRO’S NECK

Bronny was hampered by a sudden cardiac arrest during a warmup over the summer, causing him to miss the beginning of the season. He said the time missed in the summer kept him from “perfecting [his] game more.” In turn, it cost him throughout the season.

James did have three years of NCAA eligibility left, but it is difficult to turn down the opportunity to live out your NBA dream alongside your father.

LeBron once said his final year in the NBA would be with his son, so some have assumed in recent years LeBron would retire after playing with his son for one year. But, before the draft, their agent, Rich Paul, said the two were not a package deal.

It seemed odd, though, that Bronny had invites for workouts with at least 10 teams but only accepted two from the Lakers and Phoenix Suns. However, Paul says that was all “by design.”

Los Angeles Lakers guard Bronny James Jr. against the Sacramento Kings during the second quarter at Chase Center. (Kelley L Cox/USA Today Sports)

Scouts weren’t too kind to Bronny, one saying he was “not an NBA prospect.” Yes, it is early, but surely Bronny would like to shoot better than 22.2% from the floor.

Bronny and the Lakers will be back in action Sunday against the Golden State Warriors. He will head to Vegas next week, where his father is gearing up for the Olympics with Team USA.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X, and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.

Sports

'It will change your life.' Ultramarathon runners embrace pain of Western States 100

AUBURN, Calif. — The Western States Endurance Run isn’t so much a race as it is torture, spooled out slowly and sadistically over 100 miles. It’s a test of willpower, fortitude and pain tolerance more than a measure of stamina, speed or athletic talent.

It is also, one might add, a test of sanity.

Yet so many people want to attempt the world’s oldest 100-mile race, which turned 50 last weekend, that organizers use a lottery each year to wean the nearly 10,000 applicants down to a field of 375.

Spectators stand on the mountain before sunrise as they wait for runners to climb out of Olympic Valley, Calif., during the first four miles of the Western States 100 ultramarathon on June 29.

The California course begins in Olympic Valley, site of the 1960 Winter Games, and finishes in tiny Auburn, a former mining town and railroad hub in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Along the way it climbs nearly three miles up steep, craggy points and plunges more than four miles down narrow canyons. The course is so challenging, calling it a run is more aspirational than factual since all but the fastest racers hike about 20 of the 100 miles.

“It’s the legends, it’s the history, it’s the stories that spread out over more than 50 years that make Western States really, really special,” said John Trent, a former sportswriter and Western States board member who has finished the race 11 times.

“It will change your life. It’ll change the way you view yourself and, more importantly, the way you view others.”

Because ultramarathons — any race longer than the traditional 26.2-mile marathon distance — are as egalitarian as they are fatiguing, aside from the trophy given to the top male and female runners and a few age-group awards, everyone who finishes Western States in less than 30 hours gets the same handmade belt buckle, in either silver or bronze. They’ve become the most prestigious finisher’s prize in the sport.

But that’s not why people run.

“You’re racing against yourself, seeing what you’re capable of doing,” said William Shaw, a 52-year-old from Georgia who ran the race for the first time last weekend. “It’s amazing.”

1

2

3

1. A runner casts a long shadow as he runs west out of Michigan Bluff during competition in the Western States 100 on June 29 in Auburn, Calif. 2. Aid station volunteers cool off Cole Watson during a stop at the Devil’s Thumb aid station. 3. Runner Tyler Green crosses the Middle Fork of the American River at Rucky Chucky.

And when you’ve shown what you’re capable of doing, you come back to do it again. That’s why Luanne Park returned to Olympic Valley after an 11-year absence to run the race for the 13th time.

At 63, Park, a retired art teacher from Mt. Shasta, doesn’t need another belt buckle; she’s already won 10 and given most of them away. Nor does she have anything left to prove. A former world-class triathlete who ran in the first U.S. Olympic trials in the women’s marathon, Park has run 166 ultramarathons, finishing as high as second at Western States and once completing the course in less than 20 hours.

“It’s like, ‘What can the human body do when you treat it nice?’ I want to see what my potential is at this stage,” Park said. “I can still challenge myself. I just happen to have gray hair now and some wrinkles.”

Luanne Park, right, hikes over Cougar Rock during the 2024 Western States 100.

Her support crew, the people who met her at the aid stations along the course to refill her water bottles, provide her with mashed potatoes, turkey wraps, pudding and Ensure and bathe her in ice, featured women from different stages of her life.

There was Renee Thomas, her wife and partner of 37 years and a former triathlete; Linda McGuire, a childhood friend from Chico and a former winemaker whose father ran Western States in 1986; Donna Riddell, Park’s best friend from her Mt. Shasta years; and Annie Phillips, her college roommate and track teammate at Oregon State.

“It’s something she wanted to do for so long but she knows, logistically, that this is the end of competing on this level,” Thomas said the night before the race over a pasta dinner in the home the women rented for the race. “She is kind of preparing herself that, ‘I’ve just got to be OK with whatever happens.’”

But she wasn’t OK. Park began the race battling neuropathy that left her feet, hands and legs numb; depression that made it difficult to train; and circulation issues that forced her to run in knee-high compression socks.

And with the word “Persevere” tattooed on one arm.

1

2

3

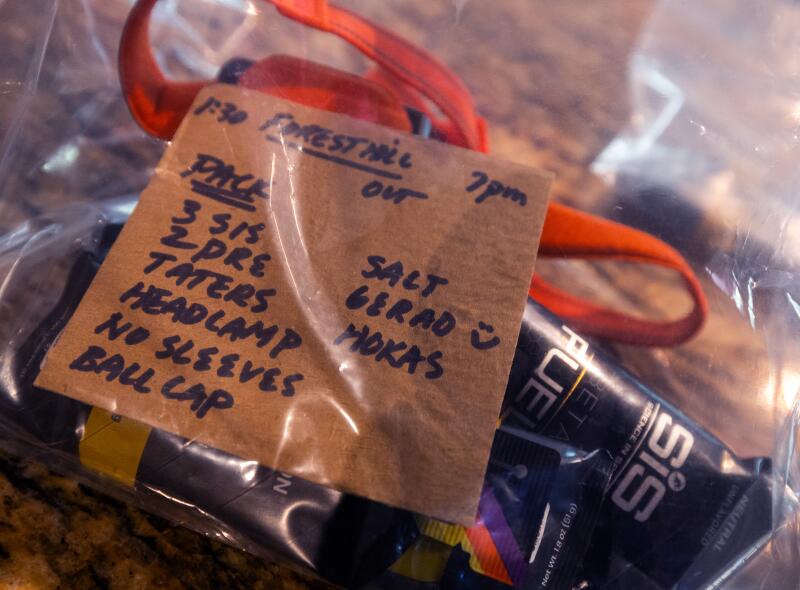

1. Luanne Park prepares her running shoes the night before competition in the Western States 100 on June 28 in Olympic Valley, Calif. 2. Luanne Park prepared items for an aid station drop the night before competition in the Western States 100 June 28 in Olympic Valley, Calif. 3. Luanne Park, center, is toasted during dinner with her support team the night before competition in the Western States 100 on June 28 in Olympic Valley, Calif.

“It’s a paralyzing thought of having to stand on that starting line knowing that my body’s not nearly at 100%,” she said. “This race is a huge question mark. Whatever that time is when I cross the fire line, that needs to be good enough.

“It is scary.”

After waiting 11 years for her lottery number to come up, giving her a spot in the race, there was never any doubt she would run. Nor, in her mind, was there any doubt she would finish. In fact, only two of the 375 people who stepped to the starting line had finished more Western States than Park.

“Every one of us that was at that starting line June 29, this was our Olympics,” Park said.

Western States is among the best-known ultramarathons in the world, though it was born mostly by accident.

For 19 years, equestrians rode the 100-mile trail from Olympic Valley to Auburn, often finishing in about half a day. But the course was considered far too long and rugged for someone to cover on foot in less than 24 hours.

It was “universal opinion” that it was “beyond the powers of human endurance” to cover 100 miles of rough mountainous trail on foot that quickly, insisted Wendell Robie, who organized the Western States Trail Ride.

Top, Shannon Krogsrud, 35, of Auburn, has a big smile after climbing four miles out of Olympic Valley during the Western States 100 on June 29. Bottom, Daniel Jones climbs out of a canyon to the Devil’s Thumb aid station during the Western States 100 on June 29.

Robie was proved wrong within days of making that statement, and Gordy Ainsleigh, a 27-year-old woodcutter, novice horseback rider and former high school cross-country runner, was the unlikely mythbuster.

Until the morning of Aug. 3, 1974, Ainsleigh’s greatest competitive achievement had been winning the Sierra College pancake-eating tournament. Large and athletic with a neat beard and a mane of blond hair that fell to his shoulders, Ainsleigh rode in the trail race a couple of times, but because of his size, he had to dismount and walk much of the course alongside his horse.

When his horse went lame, preventing him from finishing the 1973 race, another rider jokingly urged him to compete the next year without a steed since he usually spent more time on foot than in the saddle.

Ainsleigh accepted the challenge and, wearing shorts and a white Western State Trail Ride T-shirt, he set off just before dawn. He finished before the next sunrise, arriving in Auburn in 23 hours 42 minutes, doing a series of cartwheels at the finish.

A runner heads west out of Michigan Bluff during competition in the Western States 100 on June 29 in Auburn, Calif.

It wasn’t exactly Roger Bannister breaking four minutes in the mile, but a barrier had fallen just the same — especially for Ainsleigh, who went on to become a chiropractor, second-degree black belt in karate and an elite rock climber.

“It was a real turning point in my life,” he said years later. “It occurred to me that maybe there were a whole bunch of other things I thought I couldn’t do.”

Runners cross the steep trail climbing out of Olympic Valley during the first four miles of the Western States 100 on June 29.

Ainsleigh, who still competes in ultras at 77, ran Western States for the 22nd and final time in 2007. He finished 12 of those races in less than 24 hours. And the race he gave birth to became so popular, a record 9,388 runners completed a 100-kilometer or 100-mile trail qualifying race with names like Cruel Jewel, Worlds End and the Georgia Death Race and promised to pay a $450 entry fee before entering the lottery for one of the coveted spots at the starting line. That arduous screening process is one reason Western States has had relatively few serious injuries and no deaths in 50 years.

If you win the lottery, you also get a cheery participant guide that warns of renal shutdown, heat stroke, hypothermia, altitude sickness, poison oak and bears, among other things. Nearly 300 starters in this year’s race were running it for the first time and their reward started with a lung-crushing, 4½-mile climb from the ski resort at Olympic Valley to Emigrant Pass, more than a mile and a half above sea level.

Making the 2,550-foot ascent to the pass is a significant achievement. Yet the Western States runners still have more than 96 miles to go.

The trail covers some of the most scenic and unforgiving terrain in North America, following a narrow path past granite clefts and through forests of towering Ponderosa pines, fir, cedar and oak trees. Native Americans trekked the same path for thousands of years to hunt, fish and forage for food. Then in the middle of the 19th century, when gold and silver mines popped up in the area, the Western States Trail became the main highway for transporting mining equipment and other essentials over the mountain peaks and into the steep canyons.

Runner Daniel Jones crosses the Middle Fork of the American River at Rucky Chucky during the Western States 100 on June 29 in Auburn, Calif.

“The course is so different from top to the bottom,” Park said. “It’s like going through different time zones. You’re definitely going through different environments.”

This year’s race began in 48-degree temperatures, just as the sun began peeking over the mountains. But by the time Park made it to Robinson Flat, the first major aid station, it was 26 degrees warmer and a blazing sun was shining down from a cloudless sky.

It took her 7 hours 50 minutes to cover the first 30.3 miles, leaving her more than 80 minutes behind schedule to finish within 24 hours. That was the least of her problems, though, because when Park entered the aid station, she headed straight for the medical tent, dropping listlessly into a folding chair.

Spectators use headlamps to guide the way out of Olympic Valley during the Western States 100 on June 29.

Park’s pulse was racing at 170, while her blood pressure was a weak 90 over 60. As she downed water and two containers of pickle juice in an effort to hydrate, medics considered whether to let her continue. After 14 long minutes, she was allowed to join Thomas and the rest of her crew, who helped her change shoes, refill her water bottles and drop cubes of ice inside her singlet.

“I’m OK,” said Park, a slight, intense woman whose dark tan and close-cropped hair leave her looking at least a decade younger than the age on her driver’s license. “I’m doing this for myself. I don’t really care what my time is. If they want to pull me [out], they can pull me. But they’re going to have to pull me.

“I’m running with my heart now and not my head.”

Park’s prerace plan called for her to spend no more than two minutes in each of the 19 aid stations, small pop-up cities of vinyl canopies and folding tables where some of the race’s 1,600 volunteers hand out water, ice, snacks, energy bars, gels and a wide array of food. Yet she had been forced to spend almost 20 minutes at Robinson Flat before finally shuffling down the narrow, rocky path toward Michigan Bluff, the next major aid stop 25 miles away.

The course plunged more than 4,000 feet over the next 16 miles and that helped Park pass about two dozen runners, leaving her first in her age group and getting her back within striking distance of 24-hour pace. But the lack of snowfall on the course exposed roots and left the trail unusually rocky, causing Park to fall three times, leaving her bare legs and white singlet torn and covered in dirt.

A runner heads west out of Michigan Bluff during the Western States 100 on June 29 in Auburn, Calif.

Making things even more difficult was the fact the course was on fire. The Creek Fire broke out in mid-afternoon, forcing evacuations at the west end of the trail, leaving the air smoky and briefly preventing support crews from accessing the two aid stations at either side of the American River, 22 miles from the finish.

Park’s crew, unaware of her struggles, followed her progress on their cellphones from beneath an E-Z Up canopy at Michigan Bluff. Then, suddenly, Park disappeared from the tracking app at a point where the course makes a steep climb. The crew’s mood shifted quickly from positive to panic before Park, in tears, called from a cellphone.

Her race, she said, was over, her head having won out over her heart. Still, it took another two hours before she allowed a race official to cut off her race wristband, officially signaling her withdrawal.

“I started thinking about my crew, all the support people, my sponsor and thinking ‘Ohmigod, I’ve got to do it,’” she said. “Then I thought, ‘You know what? This one time in my life I’m going to do something without thinking of other people’ and that led me to drop. It was like, ‘This is totally for me,’ which seems like a weird thing.”

She had been forced to hike many of the 47 miles she covered and she knew the route well enough to know that several significant climbs, a river crossing and punishing plunges to the canyon floors lay ahead.

Luanne Park, right, hugs Renee Thomas, her wife and partner of 37 years, after dropping out of the Western States 100.

Park wasn’t the only runner the trail beat that day; nearly a quarter of the field failed to make it to the finish.

Hours later Phillips, who spent much of the weekend looking for cosmic meaning in random events, told Park she interpreted her progress through the canyons as a sign.

“Yeah,” Park replied drolly. “A stop sign.”

After climbing and descending more than 40,000 feet — an elevation change more than two miles greater than Mt. Everest is tall — Western States finishes on the pool-table-flat red synthetic running track at Placer High School.

Just getting there, as Park can attest, is a victory. And the 286 who made it this year got the same kind of handcrafted belt buckle Ainsleigh received 50 years ago.

Front-runner Jim Walmsley is the center of attention as his crew tends to cooling and hydration during a stop at the Michigan Bluff aid station during the Western States 100 on June 29 in Michigan Bluff, Calif. Walmsley won the race with a time of 14:13:45.

Front-runner Jim Walmsley rests his blistered feet during a stop at the Michigan Bluff aid station on June 29 in Auburn, Calif.

Four-time champion Jim Walmsley of Flagstaff, Ariz., was the first across the line in 14 hours 13 minutes 45 seconds, winning by nearly 11 minutes. He owns the course’s fastest finish.

Katie Schide of Gardiner, Maine, successfully defended her title in the women’s race, running 15:46:57, 17 minutes off the course record. Both winners finished before dark, but the real drama didn’t begin until the next sunrise. To win the coveted silver belt buckle, runners must finish in 24 hours; finish in 30 hours and you get a bronze one.

Miss that by a second though and, officially, you didn’t finish at all.

The rules have conspired to set up the “golden hour,” one of the most emotional and inspiring traditions in running. Sixty-one finishers, about 22%, crossed the line in final hour this year and thousands of locals, along with runners and their crews, packed the grandstands, set up picnic lunches on the football field and lined the track at Placer High, ringing cow bells and cheering them on.

Water drips from front-runner Jim Walmsley’s cap during a stop at the Michigan Bluff aid station on June 29 in Auburn, Calif. Walmsley won the race with a time of 14:13:45.

“It becomes a matter of survival and just moving,” Trent said. “As long as you keep moving, you have a shot.”

For some, the respect and adulation of the final minutes on the track make it all worthwhile. But that’s also where the toll of the Western States 100 becomes real. Once-fluid runners hobble stiff-legged to the finish, while others list awkwardly to one side. Some grab at sore hips or hamstrings while others finish with bruised, bloodied and blackened limbs after taking falls on the trail.

“Never again,” said Emily Clay, a 34-year-old from Baltimore who has biked across the country but never run 100 miles in a single stretch.

Nearby Shaw, the 52-year-old Georgian, sat alone on a bench, head in hand, staring blankly at a half-eaten hamburger. He was completely drained after finishing 37 minutes before the 30-hour cutoff and 10 minutes ahead of Clay. The race, he said, was the hardest thing he has ever done.

“Absolutely. But it’s a whole lot of fun too. It’s too fun,” he said.

Sam Fiandaca, 52, of Foresthill is greeted by fans crowding the Placer High School track infield to cheer on runners as they finish the Western States 100 ultramarathon on June 30 in Auburn, Calif.

When Chris Culpepper, a 59-year-old from Houston, hit the track he doubled over in pain and with less 100 yards of the 100-mile race remaining, he simply stopped. He could see the finish line; he could probably throw a rock across it. But he couldn’t make it there on foot.

Then the crowd came to its feet, and with shouts of “Chris!” ringing in his ears, Culpepper resumed his slow shuffle, reaching the finish line with fewer than nine minutes to spare.

Seven others followed him; the last was Iris Cooper, a 65-year-old Canadian and veteran of more than 100 ultras, who was the final official finisher — and the oldest woman finisher — in 29:56.10.

But she wasn’t the last runner on the track. Mill Valley’s Will Barkan, bidding to become the first legally blind runner to finish Western States, entered the stadium with less than a minute left on the clock, then crossed the line 33 seconds after the 30-hour cutoff.

As he stumbled to a stop next to his fiancee, Kim, Barkan, carrying a plastic water bottle and wearing a red T-shirt over a long-sleeve white shirt caked with dirt and blood, he asked “Did I make it?”

“No,” came the reply.

Barkan had run through the smoke of a wildfire, fallen numerous times, stubbed his toes until his shoes filled with blood and battled a sore knee. But he was 33 seconds too late to make any of that count. The official results do not include his name.

Yuki Naotori, 51, of Fukuoka Japan, kneels on the track at Placer High after crossing the finish line in the Western States 100 Sunday, June 30, 2024 in Auburn, CA.

Yet Barkan, like Park and every other runner who has stepped to the Western States starting line, did so looking not for glory, fame or even a belt buckle. The race was never about any of that. When Ainsleigh ran the trail for the first time 50 years ago, he was running simply to prove he could do it. Everyone who has followed ran to prove the same thing.

So while hours may have separated Barkan from the trophy Walmsley received and seconds may have separated him from a bronze belt buckle, he didn’t leave the track at Placer High empty-handed. Or even disappointed.

He left it the way every Western States runner does — as a champion.

“It’s a rare honor to be here,” he told reporters. “I feel super lucky I got a chance.”

-

Politics1 week ago

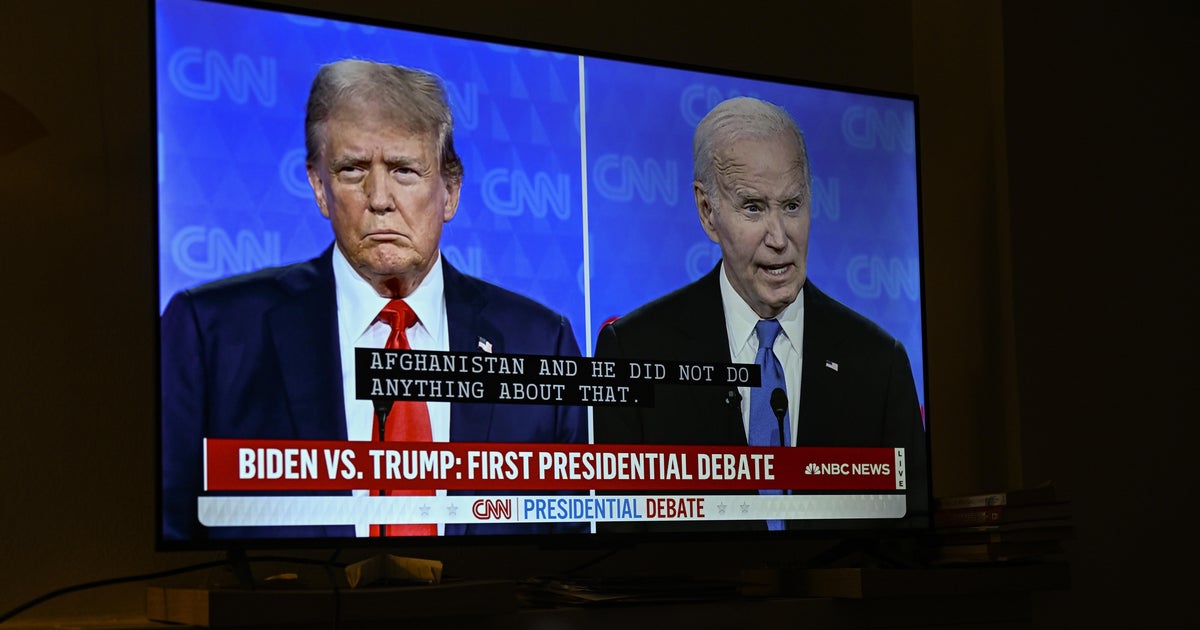

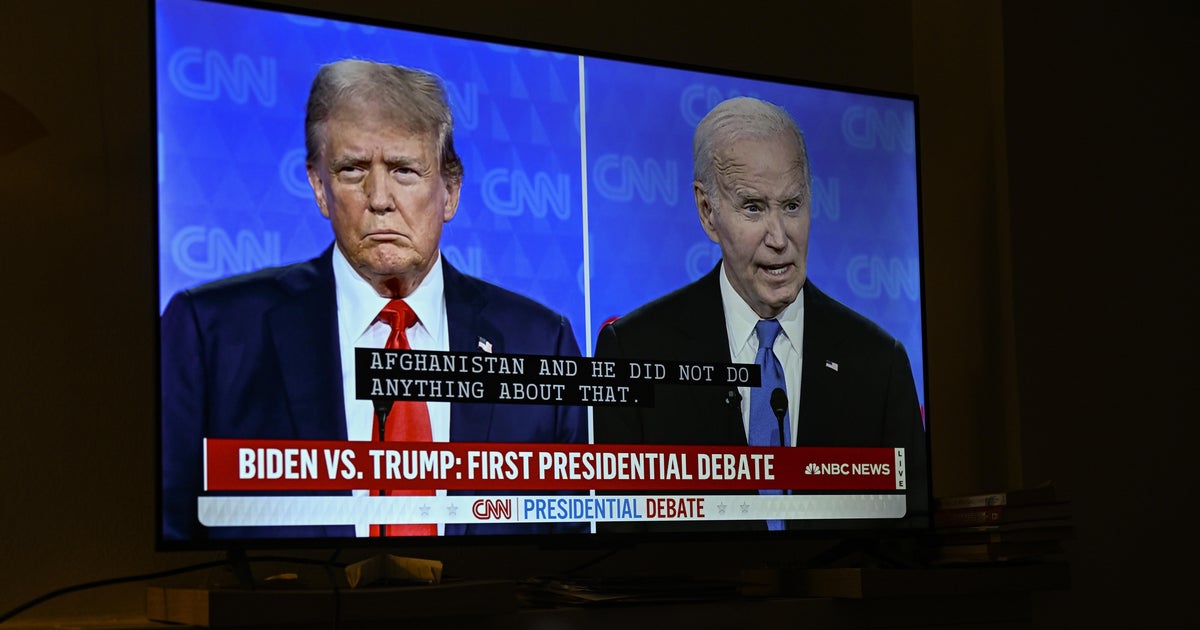

Politics1 week agoThe many faces of Donald Trump from past presidential debates

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTension and stand-offs as South Africa struggles to launch coalition gov’t

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFirst 2024 Trump-Biden presidential debate: Top clashes over issues from the border to Ukraine

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago4 killed, 9 injured after vehicle crashes into Long Island nail salon

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court denies Steve Bannon's plea to stay free while he appeals

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: How Blast Waves Can Injure the Brain

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump says 'biggest problem' not Biden's age, 'decline,' but his policies in first appearance since debate

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIncreasing numbers of voters don’t think Biden should be running after debate with Trump — CBS News poll