Oklahoma

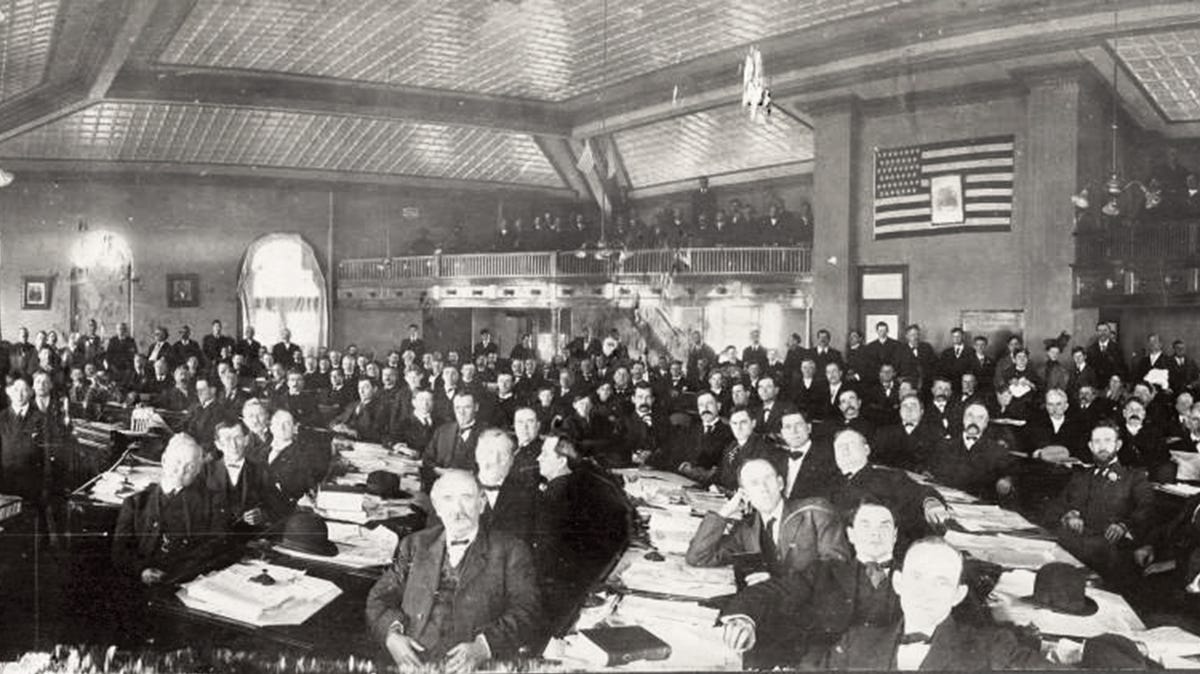

How a petition filed in secrecy helped move Oklahoma’s capital from Guthrie to OKC

Ballot initiatives has long been used by Oklahoma voters to address issues bypassed by the Legislature. Yet for more than a decade now, that process has been under fire. In 2023, lawmakers filed at least five bills to tighten access to initiative petitions.

More proposals to change the process are expected next year.

Supporters say ballot initiative process gives the public the opportunity to check their lawmakers. Opponents counter the process is a two-edged sword — giving bad ideas the necessary oxygen to survive.

Still, only a few ballot initiatives have dramatically impacted the state, and one changed the entire face of state government.

That was the case at the turn of the century, just a few years after Oklahoma joined the Union. Then-Gov. Charles Haskell used a ballot initiative as the capstone to a 20-year battle that would move the seat of state government.

How the location of Oklahoma’s capital wound up in the hands of voters

The story of Haskell’s Initiative Petition No. 7 has long been steeped in mystery, more than one broken law and an early range war between Oklahoma City and neighboring Guthrie.

The governor, records show, wanted out of Guthrie. Guthrie, a Republican strong-hold at the time, rankled Haskell, a conservative Democrat. Haskell, along with William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, the speaker of the House, had successfully steered Jim Crow legislation through both Houses of the Legislature.

Guthrie’s Republicans regularly complained about Haskell, and the governor, already sensitive to the editorials of Guthrie’s largest newspaper, the Daily State Capitol, told supporters he’d had enough.

Haskell, with the help of several Oklahoma City business leaders, including The Daily Oklahoman publisher E.K. Gaylord, make their next move — a secret scheme to move the Capitol to Oklahoma City.

Written in 1909 with the support of Haskell and a small group of his supporters, Initiative Petition No. 7 asked voters where they wanted the Capitol located. Voters were given three choices: Guthrie, Oklahoma City or Shawnee.

Gaylord said the petition was written by his attorney, W.A. Ledbetter.

Once finalized, distribution of Ledbetter’s initiative petition began almost immediately. With help from circulation men from his newspaper, Gaylord said the petition was spread across the state and quickly gathered enough signatures to be filed.

More: Would Oklahoma voters approve an increase in the state’s $7.25 minimum wage?

Detailed in an unpublished interview with Oklahoman reporter Otis Sullivant — and archived now with the Oklahoma History Center — Gaylord told the story of how he, Haskell and others got petition circulated and signed.

“I got our circulation men to circulate it (the petition) all around the state,” Gaylord told Sullivant. “We got sufficient number and then we got the election set down for that and sent all kinds of speakers out all over the state and we even had as many as four special trains at once going out in all different directions.”

On June 21, 1909, the proposal listed in the name of A. B. Newbern, an employee of The Daily Oklahoman, was filed with then-Secretary of State Bill Cross. The petition had received a total of 39,764 signatures for the constitutional amendment and 27,944 signatures for the location bill.

No records exist that show the petition’s signatures were ever verified or what methods were used by the Oklahoman’s circulation staff to gather those signatures.

Haskell and his supporters believed the signatures were enough to place the measure on a ballot. Still, somehow, despite its public circulation, opponents of the petition were kept in the dark long enough that the five-day protest period — as required by state law at the time — passed before they were aware the petition was viable.

Opponents were kept in the dark about the petition

In 1909, the Oklahoma Constitution’s initiative and referendum clause required all petitions proposing legislation have a five-day notification period. Once the petition had been filed with the secretary of state’s office. That protest period, the founders believed, would give opponents time to mount their objections.

Because the group led by Haskell and Gaylord had secretly agreed to hide the petition — bypassing the state law — the petition passed through the notification period without public knowledge of who was behind the proposal and subsequently, without any challenge.

Cross’ assistant at the time, Leo Meyer, said he helped keep word of the petition quiet.

“I filed it in Guthrie at midnight,” Meyer said in an 1933 interview with the Works Progress Administration. That interview, also archived at the Oklahoma History Center, detailed out the scheme that Haskell, Gaylord and others used to call a public vote and move the Capitol.

“When there was no danger of anyone, but the parties involved, knowing it. There was an agreement between members of the committee that everything would be held strictly confidential and that no information would ever be made public,” Meyers said.

For five days no newspaper in Oklahoma, including The Daily Oklahoman, published stories about the petition. Then, on July 27, the sixth day after the petition had been filed, the Kansas City Journal printed a story about the plan to move the capital.

Legal fight over the initiative to move Oklahoma’s capital begins

Guthrie residents, furious by the scam, turned to the courts. Logan County Judge Frank Dale filed a writ of mandamus and called for a hearing. Dale charged the filing was purposely hidden to “prevent this plaintiff and all other persons from filing objections to said petition within five days as allowed by law.”

Despite its questionable birth, the petition found its way from Cross to Attorney General Charles West for review.

The legal fight over the proposal continued until Jan. 10, 1910, when West sent the ballot title to Haskell. Two months later, Haskell issued the gubernatorial proclamation required for a special election — with a twist.

Though the original petition sent to the governor had an election date of Tuesday, June 14, 1910, Haskell scratched out the date and in his own hand wrote in a new one: Saturday, June 11 — three days before the Tuesday, June 14, election date.

The Saturday vote, records show, was the only time in state history a statewide vote was set for a weekend. Records show that Haskell took a train to Tulsa to await election returns and, somehow, managed to have the entire statewide vote canvassed in just a few hours.

At that time, it often took weeks to determine the come of statewide election.

Early Sunday morning, Haskell declared Oklahoma City to be the winner of the election and, in a move that has become legendary, had the state seal taken from Guthrie to Oklahoma City. In Oklahoma City, Haskell established his office at the Lee-Huckins Hotel and declared the Capitol had been moved.

Like they had before, Guthrie’s political leaders sought the help of the courts.

Less than a year later, the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled the petition was unconstitutional, but the deal was done. Guthrie had lost. The Capitol of the state would remain in Oklahoma City.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma sends aid to New Mexico, additional support to Texas to help with flood recovery

Oklahoma

Oklahoma livestock farmer killed by water buffaloes he purchased just one day before fatal attack

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

A Jones, Oklahoma, farmer was attacked and killed by a pair of water buffaloes he acquired at a livestock auction just a day earlier, according to police.

The Jones Police Department said Monday that officers responded to an emergency call just after 10:30 p.m. on Friday, regarding an individual who was attacked by water buffalo at a farm.

When first responders arrived, they were unable to reach the victim, later identified as Bradley McMichael, because of the aggressive behavior of a water buffalo.

In order to allow safe access to McMichael, officials shot and killed one of the water buffalo.

HORRIFIED TOURISTS WATCH AS BISON BOILS TO DEATH IN YELLOWSTONE HOT SPRING

FILE – A farmer in Oklahoma sustained multiple lacerations to his body from water buffaloes he purchased a day before he was attacked by the animals on July 11, 2025. (Fabian Sommer/picture alliance via Getty Images)

The officers then gained entry to the scene and discovered that McMichaels had sustained multiple deep lacerations that proved to be fatal.

When investigators were processing the scene, a second water buffalo started to become more and more agitated and began to pose a threat to emergency personnel.

Police said the second animal was killed to ensure everyone on the scene was safe.

YELLOWSTONE TOURIST GORED BY BISON AFTER GROUP OF VISITORS APPROACHED IT TOO CLOSELY

A preliminary investigation determined that the two water buffaloes were responsible for the fatal injuries McMichael sustained.

Investigators also learned McMichael purchased the two water buffaloes at a livestock auction on July 10, just a day before he was killed.

‘UNHAPPY COW’ SENDS TEXAS RANCHER FLYING TO HOSPITAL IN AIRLIFT RESCUE AFTER UNEXPECTED ATTACK

FILE – An Oklahoma man was attacked by two newly acquired water buffaloes on his farm on July 11, 2025. (Michael Bahlo/picture alliance via Getty Image)

Detectives suspect McMichael became trapped inside the water buffalo enclosure while he was tending to his new animals.

Amy Smith, McMichael’s ex-wife, told television station KFOR his passion was caring for livestock.

“The cattle farming, that’s his thing,” Smith told the station. “He’s been here his whole life, and he’s done that his whole life.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“So, he’s an experienced cattle handler and a farmer,” she added.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Oklahoma

Detroit Tigers select RHP Malachi Witherspoon with No. 62 pick in 2025 MLB Draft

What Scott Harris learned from Theo Epstein to improve Detroit Tigers

The “Days of Roar” podcast talks with ESPN’s Jesse Rogers about what lessons Scott Harris gained from Theo Epstein to mold the Detroit Tigers.

The Detroit Tigers selected Malachi Witherspoon, a right-handed pitcher from the University of Oklahoma on Sunday, July 13, in the second round of the 2025 MLB Draft, with the No. 62 overall pick.

Witherspoon had a difficult path to the MLB draft. Raised by a single mother, Meg, with two other siblings, he and his twin brother, Kyson, have forged a path in baseball after playing hockey and gymnastics. Kyson was drafted No. 15 overall by the Boston Red Sox.

Malachi was the more touted prospect as the brothers began college at Oklahoma, and even received an over-slot offer following the 2022 draft, in which he was a 12th-round pick by the Arizona Diamondbacks. But with the Sooners, Kyson, undrafted in 2022, moved up the draft boards.

The 6-foot-3, 211-pound Malachi Witherspoon features a fastball peaking at 99 mph. But he struggled with control in the zone, according to scouts. His fastball in particular was well-hit at Oklahoma, suggesting he may need to remake its shape entirely to succeed in the big leagues. When he throws pitches such as his curveball with depth, he tends to have more success.

Witherspoon was the No. 121 prospect in this year’s draft, according to MLB Pipeline. The 20-year-old is the third second-round pick selected by Tigers president of baseball operations Scott Harris. In 2023, Harris selected second baseman Max Anderson at No. 45 overall from Nebraska. In 2024, he selected pitcher Owen Hall at No. 49 overall from Edmond North High School in Oklahoma.

Buy our book: The Epic History of the Tigers

The Tigers earlier Sunday picked Jordan Yost, a shortstop from Sickles High School, Florida, with the No. 24 overall pick in the first round. The Tigers selected another high schooler in power-hitting catcher Michael Oliveto, with their second pick at No. 34 overall in the Competitive Balance Round A. They wrapped up Day 1 of the draft by selecting Arizona State left-hander Ben Jacobs in the third round, at No. 98 overall.

The No. 62 pick comes with a recommended bonus slot value of $1,451,200, though teams can exceed that to sign picks as long as they do not exceed their total bonus pool. If the Tigers sign the No. 62 pick for less than slot, those savings can be applied to other picks in the draft. The Tigers have $10,990,800 to spend on their 21 draft picks this year, the 17th-most in baseball. Teams are allowed to exceed the allotment for picks by 5% before paying a 75% fine on the overage. No MLB team has exceeded the 5% limit since the slots were created.

[ NEW TIGERS NEWSLETTER! Sign up for The Purr-fect Game, a weekly dose of Tigers news, numbers and analysis for Freep subscribers. ]

Day 1 of the draft features the first three rounds, with Day 2 on Monday, July 14, featuring Rounds 4-20, beginning at 11:30 a.m. on MLB.com. The Tigers have 21 picks in total.

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry to Match These Snarky Quotations to Their Novels and Stories

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoVideo: Trump Compliments President of Liberia on His ‘Beautiful English’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTexas Flooding Map: See How the Floodwaters Rose Along the Guadalupe River

-

Business1 week ago

Companies keep slashing jobs. How worried should workers be about AI replacing them?

-

Finance1 week ago

Do you really save money on Prime Day?

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoApple’s latest AirPods are already on sale for $99 before Prime Day

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoVideo: Clashes After Immigration Raid at California Cannabis Farm

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoJournalist who refused to duck during Trump assassination attempt reflects on Butler rally in new book