This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Verite News. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Louisiana

New Louisiana Law Serves as a Warning to Bystanders Who Film Police: Stay Away or Face Arrest

Four years before a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, prompting nationwide demonstrations, hundreds of people marched in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to protest officers’ killing of Alton Sterling in front of a convenience store. Law enforcement responded in force: Officers armed with rifles, body armor and gas masks pushed protesters back and forcibly arrested about 200 people. Some were injured.

A group of 13 protesters and two journalists filed suit, alleging their constitutional rights were violated when they were arrested. Eventually, the city agreed to pay them $1.17 million. Photographs and videos taken by protesters, witnesses and journalists were critical in contradicting officers’ claims that protesters were the aggressors, said William Most, an attorney for the plaintiffs.

On Thursday, a Louisiana law will go into effect that will make it a misdemeanor for anyone, including journalists, to be within 25 feet of a law enforcement officer if the officer orders them back. The two independent journalists who sued, whose photos were used to support allegations against the police, said they wouldn’t have been able to capture those images if the law had been on the books during the protests.

Karen Savage was working for a news site focused on juvenile justice issues on the second day of the demonstrations in July 2016 when she photographed officers putting a Black man in a chokehold as they detained him. Cherri Foytlin, who was working for a small newspaper and a community media project, said she was within 4 feet when she photographed officers violently dragging a Black man off private property and arresting him.

Foytlin and Savage said they are hesitant to cover protests in Louisiana now that they could face criminal charges if they’re too close to an officer. “I was thinking about how far exactly 25 feet is, and, at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter. It’s going to be whatever the officer wants it to be,” Savage said. “And if it doesn’t get to court, it won’t matter because they will have accomplished what they wanted, which was to get the cameras away.”

On Wednesday, a coalition of media companies representing a couple dozen Louisiana news outlets, including Verite News, filed suit against Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill, State Police Superintendent Robert Hodges and East Baton Rouge District Attorney Hillar Moore III, alleging the law violates the First Amendment.

Police buffer laws, as they are commonly known, are relatively new; Louisiana is the fourth state to enact one. Although those states already prohibit interfering with police officers, supporters say buffer laws are necessary to protect police from distrustful, aggressive bystanders. And with advances in cellphone cameras, including zoom lenses, supporters say there’s no need to get close to officers in order to record their activities.

“There’s really nothing within a 25-feet span that someone couldn’t pick up on video,” Rep. Bryan Fontenot, R-Thibodaux, the sponsor of Louisiana’s bill and a former law enforcement officer, said during a legislative hearing this year. At the same time, he said, “that person can’t spit in my face when I’m making an arrest.” (He did not respond to a request for comment.)

Foytlin disagreed. “You can’t even get an officer’s badge number at 25 feet. So there’s no way to hold anyone accountable.”

She and Savage said police targeted them during the Baton Rouge protests because they were taking photos of protesters being slammed to the ground, dragged across the pavement, choked and zip-tied by law enforcement officers. Both journalists were charged with obstructing public rights of way and resisting arrest. Prosecutors did not pursue those charges.

The journalists and protesters sued the city of Baton Rouge, the East Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff’s Office and the Louisiana State Police, claiming law enforcement officers had used excessive force when arresting them. The Sheriff’s Office was dismissed as a defendant because a judge concluded its deputies weren’t involved with those arrests. The State Police settled for an undisclosed amount in 2021. The suit against Baton Rouge went to trial in 2023; the city agreed to the million-dollar settlement the day before closing arguments.

Neither the Sheriff’s Office nor the Baton Rouge Police Department responded to requests for comment. The Louisiana State Police declined to comment on the lawsuit or protests.

Foytlin said she didn’t think the settlement would cause law enforcement agencies to change their tactics; now, she believes they’ll be emboldened by the buffer law to crack down more harshly on anyone trying to document officers’ actions.

“From what I saw in Baton Rouge, and what they were able to get away with, I have no doubt that in the future, the consequences of trying to use your free speech or to protest are going to be much harsher,” she said.

“You Can’t Tase a Child.” “Watch me.”

Given the inconsistent use of police body-worn cameras, said Nora Ahmed, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Louisiana, often the only way people can guard against false charges and prove that officers used excessive force is to film them in close proximity. “In the absence of video or audio evidence,” she said, “it’s very difficult to convince anyone that the story occurred in any way different other than what the police report.”

Such video was critical in a lawsuit Ahmed handled in which a woman sued two sheriff’s deputies over her arrest in St. Tammany Parish, across Lake Pontchartrain from New Orleans.

The May 2020 incident started with an anonymous complaint about someone riding a motorcycle without a helmet in a Slidell neighborhood, according to the lawsuit. Deputies Ryan Moring and Kyle Hart showed up at Teliah Perkins’ home, writing in an incident report that they saw Perkins ride a motorcycle without a helmet. In Perkins’ lawsuit, she denied doing so.

The conversation quickly became heated. Perkins accused the deputies of harassing her because she is Black; the deputies wrote in the incident report that she was “irate” and verbally attacked them.

Perkins called for her son De’Shaun Johnson, then 14, and her nephew, then 15, to come outside and record what was happening, according to the deputies’ incident report and the videos. When they did, at least one of the deputies ordered them to go back on the porch, which was more than 25 feet away.

The boys ignored the deputies and continued to film from about 6 feet away. As Hart forced Perkins to the ground, Moring approached Johnson, shoving him and telling him to move back, according to Perkins’ lawsuit and her son’s video. When Perkins screamed that she was being choked, Moring stood in front of Johnson to block his view, he later admitted in his deposition. Moring then pointed his Taser at the boy.

“You can’t tase a child,” Johnson said, according to the lawsuit and the son’s video.

“Watch me,” Moring responded.

Perkins was arrested for resisting a police officer with force or violence, battery of a police officer, having no proof of insurance and failing to wear a helmet. She was found guilty only on the resisting charge; the others were dropped. She sued the deputies in federal court, claiming they had violated her and her son’s rights. An appeals court dismissed Perkins’ claims against the deputies, but her son’s claim against Moring went to trial. In May, a jury found that Moring had intentionally inflicted emotional distress on Johnson and awarded him $185,000, to be paid by the St. Tammany Parish Sheriff’s Office.

Ahmed said she believes the jury was swayed by videos of the incident, which showed “with clear granularity exactly what was transpiring.”

Moring denied in court that he intentionally harmed Johnson and has filed a notice of appeal. The deputies’ lawyer didn’t comment for this story.

Credit:

Kathleen Flynn, special to ProPublica

In an interview with Verite News and ProPublica, Perkins said she fears what could have happened had the new law been in effect. The boys could have been arrested when they refused to move back to the porch. And from there, she said, neither would have been able to see or hear what was happening to her.

Johnson, who is about to start his first year at Alabama State University, said the videos he and his cousin took that day are the only evidence of what actually happened. Without them, he said, no one would have believed a 14-year-old boy’s claim that a deputy had threatened to shock him with a Taser simply because he was recording with a cellphone.

After George Floyd’s Murder, a New Tool to Keep the Public at Bay

There were no police buffer laws when Floyd was murdered on a Minneapolis street in 2020. Seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier stood several feet away and recorded a video that showed Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck and back for more than nine minutes, causing Floyd to lose consciousness and die. The video was critical in securing Chauvin’s conviction for second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. He was sentenced to more than 22 years in prison.

Credit:

Minneapolis Police Department via AP

Floyd’s murder fueled protests across the country and efforts to rein in the police. New York City ended qualified immunity, a legal defense used to shield officers from civil liability. Many states restricted the types of force officers can use, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

The video of Chauvin “really drew people’s attention to how powerful these recordings can be in inspiring protests and legislative action,” said Grayson Clary, a staff attorney at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. “I think some legislators are now trying to claw back ground that they feel they lost.”

Arizona state Sen. John Kavanagh, a Republican from outside Phoenix who authored the first of these bills in 2022, wrote in an op-ed that police officers asked him to introduce it because “there are groups hostile to the police that follow them around to videotape police incidents, and they get dangerously close to potentially violent encounters.”

Kavanagh’s bill, which was signed into law by then-Gov. Doug Ducey, prohibited people from filming police within 8 feet. But federal courts across the country have affirmed the right to film the police, and a federal judge struck down the law after a coalition of media outlets and associations sued the state.

Indiana was the next state to pass a similar law. It, like the two others enacted since, doesn’t mention filming and requires people to stay at least 25 feet from police. That’s based on a controversial theory, often cited to justify police shootings, that someone armed with a knife can cover 21 feet running toward an officer before the officer can fire their weapon.

Shortly after the law was enacted in April 2023, an independent journalist sued the city of South Bend after an officer pushed him 25 feet from a crime scene and another officer ordered him to move back another 25 feet. The journalist claimed in the lawsuit that it was impossible to observe the crime scene from that distance. The state denied in court that the journalist’s rights were violated.

In January, a federal judge dismissed the journalist’s suit, stating that officers have a right to perform their jobs “unimpeded.” The judge said 25 feet is a “modest distance … particularly in this day and age of sophisticated technology” and that “any effect on speech is minimal and incidental.” That case is under appeal.

A second lawsuit in Indiana, filed in December by a group of news organizations and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, is pending. They are suing the state attorney general and the prosecutor and sheriff of Marion County, where Indianapolis is located, arguing that it is “essential for reporters to be within 25 feet of law enforcement in order to record them.” In a court filing, the defendants have argued that the law doesn’t infringe on reporters’ ability to record police activities.

Florida’s law went into effect in April. An early version of that bill specified that it did not apply to the act of peacefully recording, photographing or witnessing a first responder, which it called a “legitimate purpose.” That language was taken out of the bill before it was passed.

Rep. Angela Nixon, D-Jacksonville, proposed changing the bill’s name to “The I Don’t Want the World to See the Police Kill an Unarmed Innocent Man Like George Floyd Again, So I Want To Protect Bad Cops and Violate Free Speech Act.” Her amendment failed.

If these laws stand up to constitutional challenges, “we’re going to see more states go down this road,” said Clary of the Reporters Committee.

The effect of Louisiana’s law may be limited in New Orleans, where the police department has been under federal oversight since 2013 due to widespread abuses, including excessive use of force and racial discrimination. New Orleans Independent Police Monitor Stella Cziment said the law may violate a court-approved list of reforms, which states that police must allow people to “witness, observe, record, and/or comment” on officers’ actions, including arrests and uses of force. Another provision says officers cannot arrest anyone for being nearby or recording them except under certain conditions, including risks to the safety of officers or others.

In response to questions from Verite News and ProPublica, the New Orleans Police Department said it is revising its policies to account for the new law, and those policies could “restrict officers’ actions” more than the law does. The NOPD said the Department of Justice and a team of court-appointed monitors will review any changes; neither responded to requests for comment.

However, the Louisiana State Police, which recently sent a contingent of troopers to New Orleans under a directive from Gov. Jeff Landry, does not have to abide by the terms of the consent decree, according to a federal judge. As such, troopers are free to invoke the new law.

The State Police is being investigated by the Department of Justice following a 2021 Associated Press investigation that uncovered more than a dozen incidents over the past 10 years in which troopers beat Black men and sought to cover up their actions. The State Police didn’t respond to a request for comment on those incidents.

When asked how troopers are being trained to use the new law, State Police spokesperson Capt. Nick Manale said only that they undergo regular training on how to engage with the public. The State Police, Manale said, “strives to ensure a safe environment for the public and our public safety professionals during all interactions.”

Louisiana

Officials confirm Pensacola Beach residue is algae, not oil from Louisiana spill

PENSACOLA BEACH, Fla. — A local fisherman raised concerns about the substance now coating Opal Beach, citing a recent oil spill off the coast of Louisiana.

WEAR News went to officials with the Gulf Islands National Seashore and Escambia County to find out the cause.

They say it’s not related to an oil spill, but is in fact algae.

The Marine Resources Division says they can understand beachgoers’ concerns, and hope to raise awareness.

“You don’t even want to get near it because it’s so gooey and sticky,” local fisherman Larry Grossman said. “It was accumulating on my beach cart wheels yesterday, and it felt like an oil product.”

Grossman messaged WEAR News on Monday after noticing something brown and oozy in the sand. He says it started showing up by Fort Pickens and stretched down to Opal Beach.

Grossman said a park service employee told him it could be oil from a recent spill in Louisiana. So he took a message to social media, sparking some reactions and raising questions.

“it certainly didn’t seem like an algae bloom because I was in the water, I caught a fish and I put some water in the cooler to keep my fish cool and it almost looked like oil in it,” Grossman said. “I know some people think it’s an algae bloom, but it certainly smelled and felt and looked like oil.”

A Gulf Islands National Seashore spokesperson confirmed to WEAR News on Tuesday that the substance is algae.

WEAR News crews were at the beach as officials with the Escambia County Marines Resources Division came out take samples.

“What I found here washed up on the beach is some algae — filamentous algae, single celled algae — that washed ashore in some onshore winds,” said Robert Turpin, Escambia County Marines Resources Division manager. “This is the spring season, so with additional sunlight, our plants, they grow in warmer waters, with plenty of sunlight.”

Turpin says this algae is not harmful.

He also addressed the concerns that this could be oil, saying he’s familiar with what oil spills look like.

He says he appreciates when people like Grossman raise the concerns.

“The last thing in the world we want is something to gain traction on social media that is faults in nature that could harm our tourism,” Turpin said. “Our tourism is very important to our economy, and we want to give the right information out to the public so we all enjoy the beaches and enjoy them safely.”

Turpin says if you see something or suspect something may be harmful on the beach, avoid it and contact Escambia County Marine Resources.

Louisiana

Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry calls for amendment for teacher pay raises

VIDEO: Louisiana 2026 Legislative Session Previewed in Lafayette

At One Acadiana’s Lafayette outlook event, business and policy leaders discussed the 2026 session and what it could mean for jobs, schools and voters.

BATON ROUGE — Gov. Jeff Landry advocated for a constitutional amendment that would create a permanent teacher pay raise as well as an eventual elimination of the state income tax in an opening address to the Louisiana Legislature on Monday.

Landry pushed for the passage of Proposed Amendment 3 on the May 2026 ballot to free up money for teacher pay raises.

He said the amendment would pay down longstanding debt within the Teachers’ Retirement System of Louisiana and enable the state to afford a permanent increase in teacher income. The proposed increases are $2,250 for teachers and $1,125 for support staff.

“With a ‘yes’ vote, we can strengthen the retirement system, improve their take-home pay, and guess what? We can do it without raising taxes,” Landry said.

A bill proposing the elimination of the state income tax, which takes in about $4 billion annually, was pre-filed earlier in the year by Rep. Danny McCormick, R-Oil City. Where the money will come from to supplement the loss is currently unclear.

McCormick said in an interview with the LSU Manship School News Service that to encourage more young adults to stay in Louisiana, “we need to do away with the state income tax.”

“This is a conversation piece that hopefully we can figure out where to make cuts in the government so we can get the people their money back,” McCormick said.

But Senate President Cameron Henry, R-Metairie, said at a luncheon at the Baton Rouge Press Club that if the Legislature “can be disciplined” this session, residents could anticipate a 0.5% decrease in state income tax during next year’s session. He also said bigger tax cuts have to be planned over a longer budget cycle.

Within education changes, Landry commended the placing of the Ten Commandments in classrooms, approved by the Louisiana Supreme Court in a decision handed down last week.

“You have staked the flag of morality by recognizing that the Ten Commandments are not a bad way to live your life,” Landry said. “Students who don’t read them will likely read the criminal code.”

Landry’s budget proposed an $82 million increase for corrections services following 2024 tough-on-crime legislation that eliminated parole and probation, increased sentencing and encouraged harsher punishments.

Landry directed his criticism toward the New Orleans criminal justice system, which he feels is lacking accountability, especially in courtrooms.

“Judges hold enormous power, but they are not social workers with a gavel,” he said. “They are the final gatekeepers of public safety.”

The Orleans Parish criminal justice system relies on state and local funding stemming from revenues from fees imposed on those arrested, according to the Vera Institute. Landry said the state spends twice as much on the Orleans system as it does in East Baton Rouge Parish, the largest parish in the state.

“Being special does not mean being exempt from accountability,” Landry said.

Overall, Landry pushed for fewer and different ideas compared to the sweeping agenda he laid out at the start of previous legislative sessions. Henry mentioned at the Baton Rouge Press Club that the governor would like for this session to be a “member-driven session instead of an administrative session.”

Landry spoke only in general terms about his proposal for more funding for LA Gator, his program to let parents use state money to send their children to private schools.

“We must find a path so that the hard-earned money of parents follow their child to the education of their choice,” he said.

He has proposed doubling funding for the LA Gator program from $44 million a year to $88.2 million. The likelihood of this occurring is yet to be seen, as prominent lawmakers such as Sen. Henry are hesitant to approve an increase in funding.

Landry similarly did not mention carbon capture projects, despite the issue gaining traction from affected parish residents and lawmakers.

House Speaker Phillip DeVillier, R-Eunice, told the Baton Rouge Press Club last week that 22 bills have been filed in the House that he would consider “anti-carbon capture.”

Landry also cited data centers and other giant industrial development projects and touted his administration’s success in bringing more jobs to Louisiana and in helping to lower insurance premiums over the past year.

“May we continue to employ courage over comfort, and if we do, there is really no limit to what we can do for Louisiana,” Landry said.

Louisiana

Louisiana’s LNG exports are driving out fishermen and driving up utility bills across the U.S.

Phillip Dyson once tried working a job that wasn’t shrimping. He lasted three days on an oil rig before going right back to his boat.

“The man said, you just tell me you want the job, we’ll fire the other guy,” he said with a laugh. “I said, don’t fire that man, ’cause I ain’t coming back.”

For more than half a century, Dyson has been fishing the coastal waters of Cameron, Louisiana. Forty years ago, Cameron Parish was the top seafood port in the United States. Today, it’s ground zero for America’s LNG export boom, a multibillion-dollar industry — the U.S. is the top exporter in the world — that has reshaped the landscape, the economy, and the daily lives of the people who have lived here for generations.

When Dyson looks out from the shrimp dock now, he doesn’t recognize what he sees: spindly cranes, cylindrical cooling towers and the constant hum of the construction and processing of liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals rising above the marsh.

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

The terminals run day and night, super-cooling natural gas into liquid form where it’s loaded onto massive tanker ships for export to places like Europe and Asia.

Shrimpers like Dyson are catching about half of what they used to, driving many out of the industry.

“There used to be 200 shrimp boats in this town — down to 15,” Dyson said. “You went from a fishing town to a town that didn’t care less about the fishermen.”

Dyson is stubborn and set in his ways. Shrimping is all he knows. He doesn’t want to leave Cameron. He buried his parents here. Scattered his daughter’s ashes in the water.

“I would never want to leave her behind,” he said. “But I’m gonna have to.”

‘You’re just surrounded’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

Cameron Parish was an attractive destination for reasons both geographic and financial. It sits close to the Haynesville Shale formation, one of the country’s most productive natural gas fields, has no parish-wide sales tax and LNG companies have secured industrial tax exemptions that, according to community advocates, amount to nearly a billion dollars a year across the three operating terminals — roughly $6 million per permanent job created.

“They don’t only export gas — they export the profits,” said James Hiatt, a former oil and gas worker who founded For a Better Bayou, a southwest Louisiana environmental community organization. “That’s the key.”

The company at the center of the expansion is Venture Global, which operates the Calcasieu Pass terminal, known as CP1, just outside of Cameron. In a March earnings call, the company reported it made more than $6 billion in 2025 alone — tripling its profits from the previous year.

In an interview last year on CNBC, Venture Global’s CEO, Mike Sabel, described the company in terms residents find difficult to square with their daily reality: “Ultimately our business is that we manufacture and operate machines that produce money.”

President Donald Trump’s administration approved a second Venture Global terminal in Cameron — CP2 — just two months after taking office in 2025. Nationally, 17 new export terminals are either under construction or have won approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Six of them are in southwest Louisiana.

Robyn Thigpen, a local resident and executive director of the advocacy group Fishermen Involved in Saving Our Heritage (FISH), described the sense of encirclement many people feel.

“When you turn here,” she said, pointing in different directions from the beach in Cameron, “the cranes off in the distance is the expansion to CP1. 12 miles back into town is Hackberry LNG. Probably about 30 miles this direction is Sabine LNG. So you’re just surrounded.”

‘No shrimper can make it here’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

Last August, while Venture Global was dredging a shipping channel at CP1 — pumping out mud and sediment to clear a path for vessels — something went wrong. The company spilled hundreds of acres of sediment into the surrounding marsh.

The mud blanketed the area where Tad Theriot, a shrimper turned oysterman, had been growing his harvest. He pivoted to oyster farming two years ago, after years of declining shrimp catches made the traditional livelihood impossible to sustain.

The dredge spill devastated his oyster operation almost overnight.

“Half of them died,” Theriot said. “We lost 50% on the big ones, even more than that.”

Out on the water, the evidence was plain — oysters pulled from cages bore what his farming partner Sky Leger called “mud blisters,” deposits of silt visible inside the shell.

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

“Before you try, tell me — would you eat it if you knew that that was there?” Leger said, pointing to dark splotches on the iridescent cup of a fresh oyster. “How does that get there?”

Venture Global told More Perfect Union and Gulf States Newsroom in a statement that the “isolated discharge was quickly contained,” and that there were “no significant offsite impacts” as a result of the spill.

The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries documented increased oyster mortality near the spill site in September, and fishermen have since requested a more comprehensive government study.

To date, no significant enforcement action has been taken against the company.

But according to documents obtained by More Perfect Union, Venture Global offered some affected fishermen $20,000 — on the condition they could never sue or speak negatively about the company again. When asked about the offer, Venture Global said the company “has communicated directly” with local fishermen “to develop mitigation and remediation plans, and minimize the potential for an event like this again.”

Theriot said he’d never take the money.

“That’s not right,” he said flatly. “I have hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of oysters. I want hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Advocates like Hiatt called the settlement offers part of a pattern the company is using to sidestep accountability through financial and political power.

“After this spill, more people are understanding that these corporations don’t give a f— about you,” he said. “All they care about is how much money they can make.”

Last month, a pipeline part of an under-construction project operated by Delfin LNG ruptured near Holly Beach in Cameron Parish. The ensuing explosion resulted in “catastrophic injuries” to a contractor working for the company, according to a lawsuit filed in Texas that accused the company of negligence and failing to “ensure the pipeline was free of flammable vapors and materials.”

“It’s a reminder that these things are happening in a community that doesn’t even have a hospital,” Thigpen said, noting that the worker was taken to a hospital in Port Arthur, Texas, roughly 45 minutes away. “It’s another example of why we can’t trust these companies to do the right thing.”

‘You can’t afford this and food’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

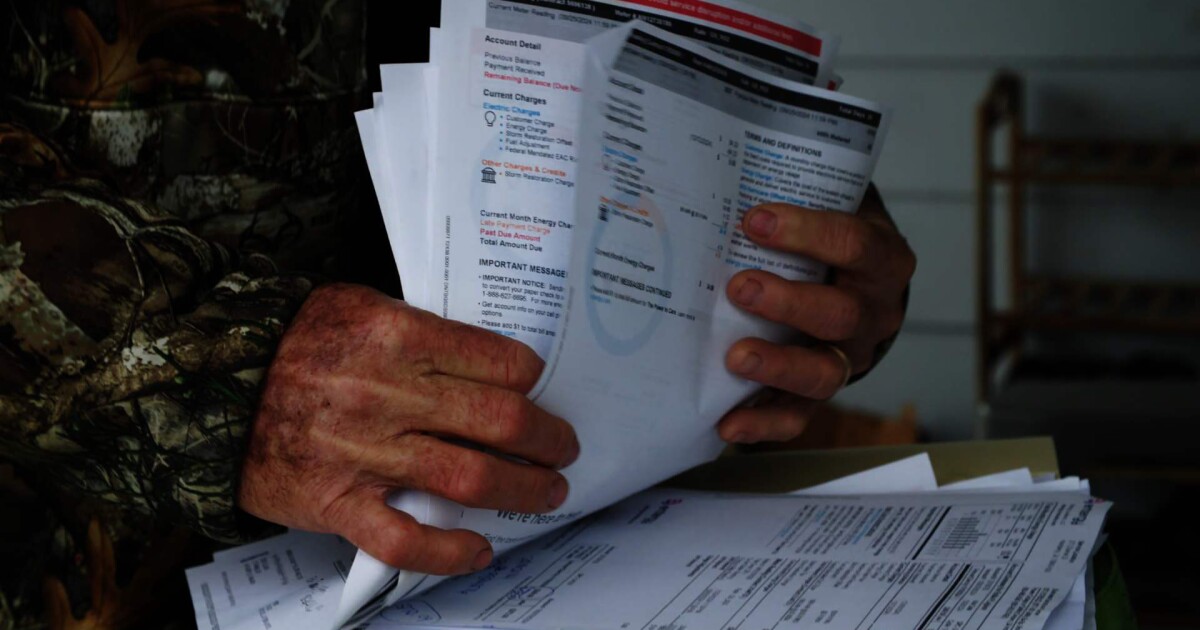

The impacts of Cameron’s transformation don’t stop at the bayou’s edge. The LNG export boom is being felt in the utility bills of Americans across the country.

Eight LNG export terminals now consume more natural gas each day than all 74 million American households connected to gas utility service combined. The federal government projects the benchmark price of natural gas will average 22% higher in 2026 than in 2025, citing LNG exports as a driving factor.

A Public Citizen analysis found domestic natural gas prices were $12 billion higher for residential customers in just the first nine months of 2025 compared to the same period the year before — roughly $124 per household.

“It’s simple supply and demand,” Slocum said. “You’re forcing Americans to compete with their counterparts in Berlin and Beijing for access to U.S. natural gas. And that pushes the domestic price up. The more we export, the higher the prices the rest of Americans will pay to heat and cool their homes.”

In Hackberry, Louisiana — minutes down the road from Cameron Parish’s other export terminal — fisherman Eddie Lejuine and his wife Michelle have watched their bills climb. Lejuine depends on a refrigerated storage container to keep his catch marketable. Without it, he can’t work.

“You can’t afford this and food,” Michelle Lejuine said. “What are you gonna do? You gonna eat or are you gonna have electricity?”

Eddie Lejuine put it plainly: “We’re catching less fish, [making] less money, paying higher bills.”

Trump’s promise, the industry’s windfall

During the 2024 campaign, Trump pledged to cut Americans’ energy bills in half within 12 months. He repeated it at rallies and put it in writing in a Newsweek op-ed.

On his first day back in the White House, one of his earliest executive orders undid former President Joe Biden’s pause on pending LNG export approvals — a pause that was implemented, in part, because consumer advocates argued the existing review process failed to account for domestic price impacts.

The ties between Venture Global and the Trump administration run deep. According to reporting by the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, the company’s CEO was present at a private 2024 meeting at which Trump reportedly asked oil and gas executives to contribute $1 billion to his campaign.

Slocum argued the gap between Trump’s promise and his policy is not an accident.

“What Trump has done is to prioritize the financial interests of the natural gas industry,” he said. “And the natural gas industry’s primary financial directive is to maximize LNG exports.”

Electricity prices jumped 6.9% in 2025 year over year, according to Goldman Sachs.

‘Find somewhere else to build this’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

More than 90% of Cameron Parish voted for Trump in 2024. The mood among the fishermen who remain is harder to categorize than partisan politics.

When asked if he’d vote for Trump again, Lejuine said: “No, I’m not. I’m hoping we have a better selection of something.”

Hiatt, a self-described third-generation oil and gas worker, framed it as a matter of basic fairness rather than ideology.

“This is ‘America Last’ policy,” he said, “to export our natural resources to the highest bidder at the expense of every American.”

Dyson, standing at the dock in the late afternoon light, said what he would tell Venture Global and the politicians like Trump and Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry, who championed the expansion: “Find somewhere else to build this s—. I never thought I’d have seen this place like this. Never in my lifetime.”

His electricity bill runs $350 to $500 a month for a 990-square-foot house, he said. He and his wife receive about $1,300 a month together on Social Security. With what he’s catching, it’s not enough.

He said he won’t stop shrimping, but he can’t do it in Cameron.

“This is what I do. That’s what I’m gonna do till they throw dirt on me. That might not be here, but I will fish till it’s over.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. This story was produced in collaboration with More Perfect Union.

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Pennsylvania5 days ago

Pennsylvania5 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Detroit, MI5 days ago

Detroit, MI5 days agoU.S. Postal Service could run out of money within a year

-

Miami, FL6 days ago

Miami, FL6 days agoCity of Miami celebrates reopening of Flagler Street as part of beautification project

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death