Science

Vesuvius Erupted, but When Exactly?

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, fiery avalanches of ash and pumice assaulted Pompeii, displacing some 15,000 inhabitants and killing at least 1,500 more. Volcanic debris “poured across the land,” wrote the Roman lawyer Pliny the Younger, and blanketed the town in a darkness “like the black of closed and unlighted rooms.” Within two days Pompeii had vanished, leaving little more than a legend until 1748, when the chance discovery of a water line prompted the first deliberate excavation.

In his late-18th-century travelogue “Italian Journey,” Goethe observed that no calamity in history had given greater entertainment to posterity than the eruption that had buried Pompeii. For scholars and armchair archaeologists, that entertainment has involved wrangling over pretty much every facet of the disaster. They still can’t agree on the day Vesuvius blew its top, the height of the umbrella-shaped cloud or the length and the aggression of the blasts. Two new research projects add kindling to those embers.

A report published by the Archaeological Park of Pompeii resurrected the once widely accepted belief that the cataclysm began to unfold on Aug. 24, the date put forward by Pliny, who was 17 when he witnessed the event from a villa across the Bay of Naples. His letters to the historian Tacitus, written more than 25 years after the fact, are the only surviving firsthand account and the only documents that offer a precise date.

We no longer have the original letters, only translations and transcriptions of copies, the first of which was made in the fifth century A.D. “Many manuscripts of Pliny’s letters came down to us with differing dates,” said the classicist Daisy Dunn. Her 2019 biography of Pliny, “The Shadow of Vesuvius,” is the definitive guide to him and his uncle, the naturalist Pliny the Elder, who died during the eruption. “Aug. 24 was chosen as the most secure on textual grounds,” Dr. Dunn said.

In sticking by Pliny, the park walked back some of the recent enthusiasm for Oct. 24 as a possible start date for the eruption, a theory that had been fueled by the 2018 discovery of a scrap of graffiti on a wall of the site’s freshly excavated House of the Garden. The charcoal scrawl records a date that translates to Oct. 17 in the modern calendar, suggesting that the eruption might have occurred after this time. The find, which did not specify a year, seemed to corroborate other unearthed clues that pointed to cooler weather than is typical in August: remnants of unripe autumnal fruits such as chestnuts and pomegranates; heavy wool clothing found on bodies; wine in sealed jars, indicating that the grape harvest was over; and wood-burning braziers in homes.

Massimo Osanna, general director of the park at the time of the discovery, was convinced that the graffiti was idly doodled a week before the explosion. “This spectacular find finally allows us to date, with confidence, the disaster,” he said. Dr. Dunn found it improbable that Pliny would have forgotten such a momentous date; still, she said, “in my view, the traditional date of Aug. 24 is just too early in the year to be accurate.”

The dating game

The park’s recent about-face from October to August relied in part on a forensic analysis of Pliny’s letters by Pedar Foss, a classicist at DePauw University in Indiana. For his 2022 book, “Pliny and the Eruption of Vesuvius,” Dr. Foss examined 79 early hand-copied manuscripts of the letters and mapped out how textural errors had been compounded. He concluded that a simple scribal mistake, made in the 1420s, of switching a “u” for an “n” had resulted in an incorrect eruption date of Nov. 1. The error appeared in the second print edition of Pliny’s letters, in 1474, and gave rise to further misreadings, misunderstandings and misuses.

By the 20th century, seven different possibilities were in circulation — eight, counting Nov. 9, which Mark Twain casually proposed in “Innocents Abroad,” his 1869 travel narrative. “Those many options gave the appearance of doubt concerning what Pliny actually wrote but, upon examination, I was able to explain away each of the mistaken alternatives,” Dr. Foss said.

He also explained away each of the archaeological alternatives to Aug. 24, some of which he believes fail based on the evidence; some, on the basis of faulty reasoning. He argued that the pomegranate rinds were used for dyeing, not eating; that the Romans commonly used braziers for cooking, not just heating; that wool clothing was standard gear for Roman firefighters; and that Roman agricultural and storage practices allowed for the preservation of fruits beyond their natural harvest seasons.

As for the House of the Garden doodle, on Oct. 12, 2023, researchers commissioned by Dr. Osanna’s successor, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, left their own charcoal message on the same wall on which the graffito appeared. Ten months later — on Aug. 24, 2024 — the text was still perfectly legible. “The inscription could have been put on the wall during October of any number of previous years,” Dr. Foss said.

So much for dating the disaster with confidence.

Letting off steam

Claudio Scarpati, a volcanologist at the University of Naples Federico II, favors the traditional date. “In my mind, the eruption occurred in August, on a sunny day,” he said. Dr. Scarpati is the lead author of two recent studies of the catastrophe published in The Journal of the Geological Society. One offered an hour-by-hour reconstruction, extending the chronology from the previously estimated 19 hours to 32 hours. The other revealed a dynamic sequence with 17 distinct “pyroclastic density currents,” many of them previously undocumented.

Pyroclastic currents are hot, swift-moving mixtures of volcanic particles — ash, pumice lava fragments and gas — that flow according to their density in relation to the surroundings. Dr. Scarpati said that contrary to popular belief, Pompeians were neither entombed by molten lava nor poisoned by gas. “No lava reached Pompeii, and the gas was predominantly vaporized water and, to a lesser extent, carbon dioxide,” he said. “According to our studies, the victims died primarily from asphyxiation caused by inhaling ash.”

To measure the distribution and the volume of the ash and the pumice layers, the team measured the thickness of the single layers over a 775-square-mile area around Mount Vesuvius. The deposits recorded dramatic, increasingly violent pulses from the volcano.

At noon on Day 1, Vesuvius began to eject a plume of rocky volcanic fragments and gas into the air, known as an eruption column. The mushroom cloud that Pliny observed at 1 p.m. was typical of what is now known as a Plinian eruption, in tribute to his richly detailed testament.

Dr. Scarpati said that the first currents had flowed to the town of Herculaneum, west of Vesuvius, bringing intense heat that essentially roasted inhabitants and, in one documented case, turned human tissue into glass, a process known as vitrification. At Pompeii, south of the volcano, the currents were cooler, and only the final eight penetrated the town.

During the first 17 hours, Dr. Scarpati said, Pompeii was blanketed with pumice lapilli from the column, which fluctuated like a giant fountain through 12 distinct pulses. At 2 p.m., the volcano began to spew pumice mixed with gas. Over the next four hours, roofs began to cave in under the weight of the pumice lapilli, causing some supporting walls to crumble as well. After 17 hours, the debris in Pompeii was up to nine feet thick. Enough was ejected to bury Manhattan roughly 450 feet, or 45 building stories, deep.

The eruption peaked when the column reached its maximum height of 21 miles, at about 1 a.m. on Day 2. “The column rose as long as its density was lower than that of the air, like a balloon,” Dr. Scarpati said. At daybreak, enormous amounts of fine ash and pumice collapsed the eruptive column, forming pyroclastic currents.

During a brief lull, Pompeians presumably tried to flee the town. Then, just after 7 a.m., the 13th and most lethal current struck — a thick concoction of ash was disgorged for nine hours, spreading detritus 16 miles across the plain and into the Lattari Mountains. In Pompeii, many victims of the volcano were found in the streets encased in this layer.

Around 4 p.m., the magma in the volcano’s conduit interacted with groundwater, causing the magma to break up into fine ash. No human remains were found in any of the layers after the 13th, suggesting to Dr. Scarpati that the morning’s devastation left no survivors. The eruption ceased at 8 p.m.

Paul Cole, a volcanologist at the University of Plymouth in England who was not involved with the project, said, “The work places a finer timeline on the events of 2,000 years ago, and also provides fresh evidence for how the hazard from such large, explosive eruptions can change even during the event.”

Rumpus involving Vesuvius may go on endlessly, but unlike Pliny’s letters, the geological history of the eruption seems to have been written in stone.

Science

Judge blocks Trump administration move to cut $600 million in HIV funding from states

A federal judge on Thursday blocked a Trump administration order slashing $600 million in federal grant funding for HIV programs in California and three other states, finding merit in the states’ argument that the move was politically motivated by disagreements over unrelated state sanctuary policies.

U.S. District Judge Manish Shah, an Obama appointee in Illinois, found that California, Colorado, Illinois and Minnesota were likely to succeed in arguing that President Trump and other administration officials targeted the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding for termination “based on arbitrary, capricious, or unconstitutional rationales.”

Namely, Shah wrote that while Trump administration officials said the programs were cut for breaking with CDC priorities, other “recent statements” by officials “plausibly suggest that the reason for the direction is hostility to what the federal government calls ‘sanctuary jurisdictions’ or ‘sanctuary cities.’”

Shah found that the states had shown they would “suffer irreparable harm” from the cuts, and that the public interest would not be harmed by temporarily halting them — and as a result granted the states a temporary restraining order halting the administration’s action for 14 days while the litigation continues.

Shah wrote that while he may not have jurisdiction to block a simple grant termination, he did have jurisdiction to halt an administration directive to terminate funding based on unconstitutional grounds.

“More factual development is necessary and it may be that the only government action at issue is termination of grants for which I have no jurisdiction to review,” Shah wrote. “But as discussed, plaintiffs have made a sufficient showing that defendants issued internal guidance to terminate public-health grants for unlawful reasons; that guidance is enjoined as the parties develop a record.”

The cuts targeted a slate of programs aimed at tracking and curtailing HIV and other disease outbreaks, including one of California’s main early-warning systems for HIV outbreaks, state and local officials said. Some were oriented toward serving the LGBTQ+ community. California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office said California faced “the largest share” of the cuts.

The White House said the cuts were to programs that “promote DEI and radical gender ideology,” while federal health officials said the programs in question did not reflect the CDC’s “priorities.”

Bonta cheered Shah’s order in a statement, saying he and his fellow attorneys general who sued are “confident that the facts and the law favor a permanent block of these reckless and illegal funding cuts.”

Science

Contributor: Is there a duty to save wild animals from natural suffering?

The internet occasionally erupts in horror at disturbing images of wildlife: deer with freakish black bubbles all over their faces and bodies, sore-ridden squirrels, horn-growing rabbits.

As a society, we tend to hold romanticized notions about life in the wild. We picture these rabbits nuzzling with their babies, these squirrels munching on some nuts and these deer frolicking through sunlit meadows. Yet the trend of Frankenstein creatures afflicted with various diseases is steadily peeling back this idyllic veneer, revealing the harsher realities that underpin the natural world. And we should do something about it.

First, consider that wild animals — the many trillions of them — aren’t so different from other animals we care about — like dogs and cats — or even from us. They love. They build complex social structures. They have emotions. And most important, they too experience suffering.

Many wild animals are suffering because of us. We destroy their habitats, they’re sterilized and killed by our pollution, and sometimes we hunt them down as trophies. Suffering created by humans is especially galling.

But even in the absence of human impact, wild animals still experience a great deal of pain. They starve and thirst. They get infected by parasites and diseases. They’re ripped apart by other animals. Some of us have bought into the naturalistic fallacy that interfering with nature is wrong. But suffering is suffering wherever it occurs, and we should do something about it when we can. If we have the opportunity to rescue an injured or ill animal, why wouldn’t we? If we can alleviate a being’s suffering, shouldn’t we?

If we accept that we do have an obligation to help wild animals, where should we start? Of course, if we have an obvious opportunity to help an animal, like a bird with a broken wing, we ought to step in, maybe take it to a wildlife rescue center if there are any nearby. We can use fewer toxic products and reduce our overall waste to minimize harmful pollution, keep fresh water outside on hot summer days, reduce our carbon footprint to prevent climate-change-induced fires, build shelter for wildlife such as bats and bees, and more. Even something as simple as cleaning bird feeders can help reduce rates of disease in wild animals.

And when we do interfere in nature in ways that affect wild animals, we should do so compassionately. For example, in my hometown of Staten Island, in an effort to combat the overpopulation of deer (due to their negative impact on humans), officials deployed a mass vasectomy program, rather than culling. And it worked. Why wouldn’t we opt for a strategy that doesn’t require us to put hundreds of innocent animals to death?

But nature is indifferent to suffering, and even if we do these worthy things, trillions will still suffer because the scale of the problem is so large — literally worldwide. It’s worth looking into the high-level changes we can make to reduce animal suffering. Perhaps we can invest in the development and dissemination of cell-cultivated meat — meat made from cells rather than slaughtered animals — to reduce the amount of predation in the wild. Gene-drive technology might be able to make wildlife less likely to spread diseases such as the one afflicting the rabbits, or malaria. More research is needed to understand the world around us and our effect on it, but the most ethical thing to do is to work toward helping wild animals in a systemic way.

The Franken-animals that go viral online may have captured our attention because they look like something from hell, but their story is a reminder that the suffering of wild animals is real — and it is everywhere. These diseases are just a few of the countless causes of pain in the lives of trillions of sentient beings, many of which we could help alleviate if we chose to. Helping wild animals is not only a moral opportunity, it is a responsibility, and it starts with seeing their suffering as something we can — and must — address.

Brian Kateman is co-founder of the Reducetarian Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reducing consumption of animal products. His latest book and documentary is “Meat Me Halfway.”

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

- Wild animals experience genuine suffering comparable to that of domesticated animals and humans, including through starvation, disease, parasitism, and predation, and society romanticizes wildlife in ways that obscure these harsh realities[1][2]

- Humans have a moral obligation to address wild animal suffering wherever possible, as suffering is morally significant regardless of whether it occurs naturally or results from human action[2]

- Direct intervention in individual cases is warranted, such as rescuing injured animals or providing fresh water during heat waves, alongside broader systemic approaches like reducing pollution and carbon emissions[2]

- Humane wildlife management strategies should be prioritized over lethal approaches when addressing human-wildlife conflicts, as demonstrated by vasectomy programs that manage overpopulation without mass culling[2]

- Large-scale technological solutions, including cell-cultivated meat to reduce predation and gene-drive technology to control disease transmission, should be pursued and researched to systematically reduce wild animal suffering at scale[2]

- The naturalistic fallacy—the belief that natural processes should never be interfered with—is fundamentally flawed when weighed against the moral imperative to alleviate suffering[2]

Different views on the topic

The search results provided do not contain explicit opposing viewpoints to the author’s argument regarding a moral duty to intervene in wild animal suffering. The available sources focus primarily on the author’s work on reducing farmed animal consumption through reducetarianism and factory farming advocacy[1][3][4], rather than perspectives that directly challenge the premise that humans should work to alleviate wild animal suffering through technological or ecological intervention.

Science

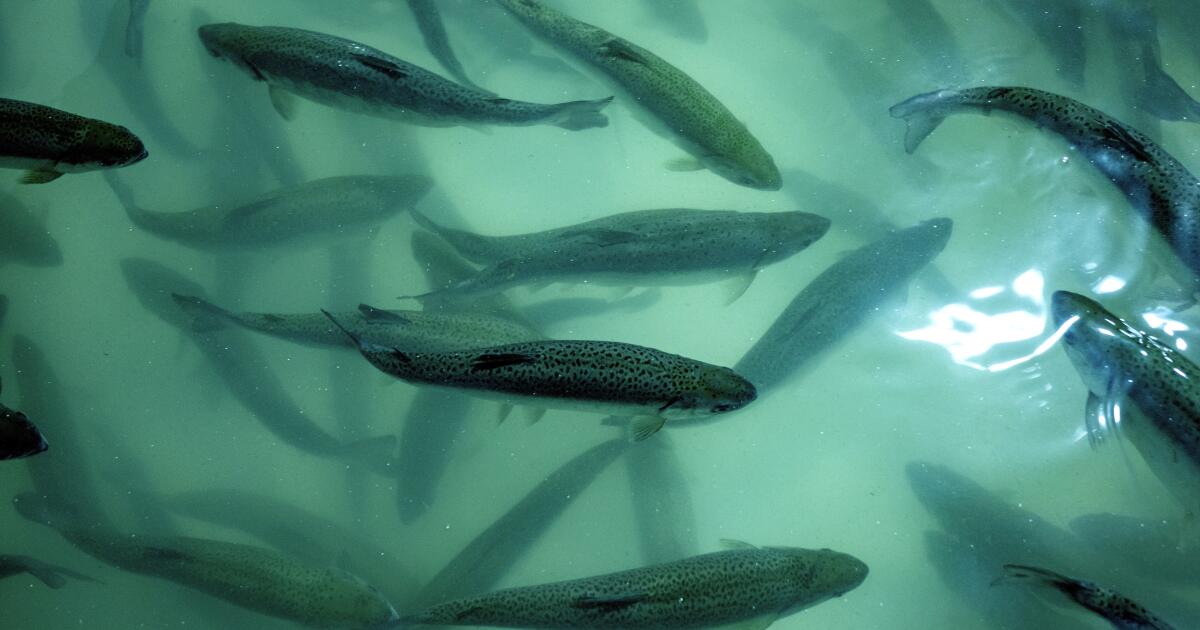

Contributor: Factory farming of fish is brewing pathogens

The federal government recently released new dietary guidelines aimed at “ending the war on protein” and steering Americans toward “real foods” — those with few ingredients and no additives. Seafood plays a starring role. But the fish that health advocates envision appearing on our plates probably won’t be caught in the crystal blue waters we’d like to imagine.

Over the past few decades, the seafood industry has completely revolutionized how it feeds the world. As many wild fish populations have plummeted, hunted to oblivion by commercial fleets, fish farming has become all the rage, and captive-breeding facilities have continually expanded to satiate humanity’s ravenous appetite. Today, the aquaculture sector is a $300-billion juggernaut, accounting for nearly 60% of aquatic animal products used for direct human consumption.

Proponents of aquaculture argue that it helps feed a growing human population, reduces pressure on wild fish populations, lowers costs for consumers and creates new jobs on land. Much of that may be correct. But there is a hidden crisis brewing beneath the surface: Many aquaculture facilities are breeding grounds for pathogens. They’re also a blind spot for public health authorities.

On dry land, factory farming of cows, pigs and chickens is widely reviled, and for good reason: The unsanitary and inhumane conditions inside these facilities contribute to outbreaks of disease, including some that can leap from animals to humans. In many countries, aquaculture facilities aren’t all that different. Most are situated in marine and coastal areas, where fish can be exposed to a sinister brew of human sewage, industrial waste and agricultural runoff. Fish are kept in close quarters — imagine hundreds of adult salmon stuffed into a backyard swimming pool — and inbreeding compromises immune strength. Thus, when one fish invariably falls ill, pathogens spread far and wide throughout the brood — and potentially to people.

Right now, there are only a handful of known pathogens — mostly bacteria, rather than viruses — that can jump from aquatic species to humans. Every year, these pathogens contribute to the 260,000 illnesses in the United States from contaminated fish; fortunately, these fish-borne illnesses aren’t particularly transmissible between people. It’s far more likely that the next pandemic will come from a bat or chicken than a rainbow trout. But that doesn’t put me at ease. The ocean is a vast, poorly understood and largely unmonitored reservoir of microbial species, most of which remain unknown to science. In the last 15 years, infectious diseases — including ones that we’ve known about for decades such as Ebola and Zika — have routinely caught humanity by surprise. We shouldn’t write off the risks of marine microbes too quickly.

My most immediate concern, the one that really makes me sweat, is the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria among farmed fish. Aquaculturists are well aware that their fish often live in a festering cesspool, and so many growers will mix antibiotics — including ones that the World Health Organization considers medically important for people — into fish feed, or dump them straight into water, to avoid the consequences of crowded conditions and prevent rampant illness. It would be more appropriate to use antibiotics in animals only when they are sick.

Because of this overuse for prevention purposes, more antibiotics are used in seafood raised by aquaculture than are used in humans or for other farmed animals per kilogram. Many of these molecules will end up settling in the water or nearby sediment, where they can linger for weeks. In turn, the 1 million individual bacteria found in every drop of seawater will be put to the evolutionary test, and the most antibiotic-resistant will endure.

Numerous researchers have found that drug-resistant strains of bacteria are alarmingly common in the water surrounding aquaculture facilities. In one study, evidence of antibiotic resistance was found in over 80% of species of bacteria isolated from shrimp sold in multiple countries by multiple brands.

Many drug-resistant strains in aquatic animals won’t be capable of infecting humans, but their genes still pose a threat through a process known as horizontal transfer. Bacteria are genetic hoarders. They collect DNA from their environment and store it away in their own genome. Sometimes, they’ll participate in swap meets, trading genes with other bacteria to expand their collections. Beginning in 1991, for example, a wave of cholera infected nearly a million people across Latin America, exacerbated by a strain that may have picked up drug-resistant adaptations while circulating through shrimp farms in Ecuador.

Today, drug-resistant bacteria kill over a million people every year, more than HIV/AIDS. I’ve seen this with my own eyes as a practicing tuberculosis doctor. I am deeply fearful of a future in which the global supply of fish — a major protein source for billions of people — also becomes a source of untreatable salmonella, campylobacter and vibrio. We need safer seafood, and the solutions are already at our fingertips.

Governments need to lead by cracking down on indiscriminate antibiotic use. It is estimated that 70% of all antibiotics used globally are given to farm animals, and usage could increase by nearly 30% over the next 15 years. Regulation to promote prudent use of antibiotics in animals, however, has proven effective in Europe, and sales of veterinary antibiotics decreased by more than 50% across 25 European countries from 2011 to 2022. In the United States, the use of medically important antibiotics in food animals — including aquatic ones — is already tightly regulated. Most seafood eaten in the U.S., however, is imported and therefore beyond the reach of these rules. Indeed, antibiotic-resistance genes have already been identified in seafood imported into the United States. Addressing this threat should be an area of shared interest between traditional public health voices and the “Make America Healthy Again” movement, which has expressed serious concerns about the health effects of toxins.

Public health institutions also need to build stronger surveillance infrastructure — for both disease and antibiotic use — in potential hotspots. Surveillance is the backbone of public health, because good decision-making is impossible without good data. Unfortunately, many countries — including resource-rich countries — don’t robustly track outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant pathogens in farmed animals, nor do they share data on antibiotic use in farmed animals. By developing early warning systems for detecting antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments, rapid response efforts involving ecologists, veterinarians and epidemiologists can be mobilized as threats arise to avert public health disasters.

Meanwhile, the aquaculture industry should continue to innovate. Genetic technologies and new vaccines can help prevent rampant infections, while also improving growth efficiency that could allow for more humane conditions.

For consumers, the best way to stay healthy is simple: Seek out antibiotic-free seafood at the supermarket, and cook your fish (sorry, sushi lovers).

There’s no doubt that aquaculture is critical for feeding a hungry planet. But it must be done responsibly.

Neil M. Vora is a practicing physician and the executive director of the Preventing Pandemics at the Source Coalition.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

Alabama6 days ago

Alabama6 days agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump unveils new rendering of sprawling White House ballroom project

-

San Francisco, CA1 week ago

San Francisco, CA1 week agoExclusive | Super Bowl 2026: Guide to the hottest events, concerts and parties happening in San Francisco

-

Ohio1 week ago

Ohio1 week agoOhio town launching treasure hunt for $10K worth of gold, jewelry

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoAnnotating the Judge’s Decision in the Case of Liam Conejo Ramos, a 5-Year-Old Detained by ICE

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoIs Emily Brontë’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ Actually the Greatest Love Story of All Time?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThe Long Goodbye: A California Couple Self-Deports to Mexico