Science

These L.A. health teams go door to door with a question: What do you need?

On a sweltering morning in Watts, community health worker Elizabeth Calvillo rapped on a shut gate with her pen, hoping the sound would carry over the rumble of an airplane.

“Good morning! ¡Buenos días!”

When a young mother emerged from the house in her pajamas, shading her eyes from the sun, Calvillo and co-worker Maria Trujillo explained they were knocking on doors to see if she or her neighbors needed anything. They asked the mother: Was she on Medi-Cal? Was there anything else she needed?

The 26-year-old said she had insurance but was tired of spending hours to get seen at a downtown clinic that said it would take months to schedule a physical for her 3-year-old daughter.

“I haven’t even gotten my checkups because it’s so hard to get an appointment,” the woman lamented.

The two promptly offered to refer her to a local clinic. Trujillo put in the referral electronically on the spot. Calvillo told her they would follow up in a week or two to make sure she had gotten an appointment.

The mother thanked them. “I’ve been stressing about it. You guys came at the right time!”

“That’s what we’re here for,” Calvillo replied.

1

2

1. Elizabeth Calvillo, left, and Maria Trujillo go door to door in Watts trying to connect people with healthcare and other services. 2. Calvillo, left, and Trujillo speak with Brenda Montes, 26, in Watts on a recent canvassing of the neighborhood. (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

In Los Angeles County, the public health department is trying to — quite literally — meet people where they are. This year, it has launched a pilot project that sends teams to knock on doors in neighborhoods like Watts, Pacoima and Lincoln Heights to ask residents what they need.

The county might be able to reach people with billboards or ads, X or Instagram, but knocking on doors is “more personal,” said Trujillo, a community health worker with Children’s Institute, one of the local groups carrying out the work. “You have an actual person coming and showing that they want to be of service to you.”

The Community Public Health Teams, run by community organizations and health groups in partnership with the county, are each tasked with knocking on anywhere from 8,000 to 13,000 doors in designated areas.

Community health workers ask questions for a household assessment — which covers unmet needs for medical care, assistance needed for day-to-day activities, mental health, housing instability, neighborhood violence and other issues — and try to connect people with services such as enrolling in Medi-Cal or finding a food bank. Each team is also linked to a healthcare partner that can offer primary care.

“This is bringing healthcare to the door of the individual,” said Monica Dedhia, director of community health programs for Children’s Institute, “versus waiting for someone to make an appointment.”

The pilot program is expected to last five years, with teams returning at least once a year to check on households. Tiffany Romo, director of the community engagement unit at L.A. County Public Health, likened it to “concierge service.” Even after someone has been linked with healthcare or other needed services, she said, the teams will reach out to them again, making sure they actually got what they needed.

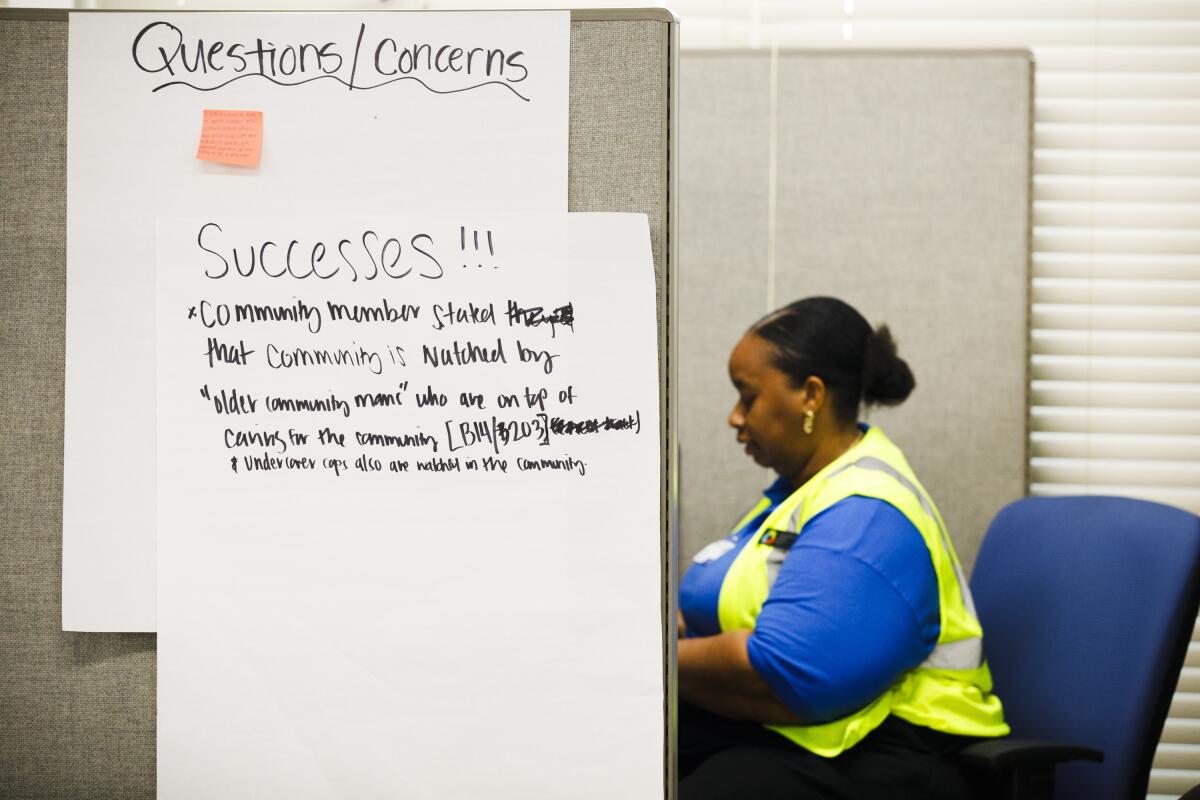

Ashley Jackson works in the Pacoima office of Providence’s Community Public Health Team, where “successes” are listed on a poster.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

It is a system more common in countries like Costa Rica and Cuba, credited with forging closer connections between health agencies and their communities. Costa Rica, which sends health workers to households, saw a drop in potential years of life lost — one that was sharper for its poorest residents than its wealthiest ones.

But it’s “rarely done in the U.S.” for health workers to be assigned responsibility for the whole population in a geographic area, “including the ones that don’t show up at clinics,” said Dr. Asaf Bitton, associate professor of medicine and healthcare policy at Harvard. “That’s a whole different orientation.”

“We know that most health is created outside the medical care system,” Bitton said, but commercial insurers do not typically pay for things like food or housing. Instead, the approach in the U.S. has largely been, “We will pay for whatever you need once you have the heart attack.”

The pilot program relies on $75 million from a federal grant that will be spread out over five years, providing $1.5 million to each team in 10 “high need” areas.

What success looks like under the program, Romo said, “is really up to the community to define.” But public health officials say their hope is it will drive down inequities and result in healthier neighborhoods. Analyzing the information it gathers will also help inform future efforts at the public health department.

L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said the pilot program emerged not only out of the successes seen in Costa Rica and Cuba, but out of the experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, when it “became abundantly clear, particularly in lower resource communities, that people were very disconnected from services and support.”

In many cases, “it wasn’t that they were necessarily uninsured or underinsured,” Ferrer said. “They just weren’t connected to a healthcare provider” or other local services. Sometimes the problem was “an information gap,” sometimes fear or distrust and sometimes barriers like long waits or burdensome paperwork, she said.

Providence’s Community Public Health Team is reflected in a mirror in Pacoima.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

In Pacoima, a working-class neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley, many “people just don’t know those resources are available,” said Dionne Zantua, program manager for another team run by Providence Health & Services Foundation.

Scarlett Diaz, a Providence community health worker, said many Pacoima residents also fear that signing up for programs such as Medi-Cal could jeopardize their chances of a green card or citizenship, even as California officials have thrown open the program to eligible residents regardless of immigration status.

Misinformation isn’t the only obstacle: As Diaz and her co-worker Ashley Jackson rounded the neighborhood one Wednesday, clipboards in hand, they faced locked gates and growling dogs. Some residents waved them off or told them to come back another time.

But their daily rounds have made a difference. Before the Providence team in their neon vests stopped at her gate, Monica Avila said she had already seen them walking her Pacoima neighborhood. The 62-year-old tried to hush her barking dogs as Diaz and Jackson began asking about anything she needed.

Avila told them about the speed bumps she wanted the city to install on her block. She told them her husband had died and one of her sons had been killed. That she used to go out dancing, but not anymore.

She told them about the anxiety she suffered, “bad anxiety where like I feel like I’m being locked in,” so bad it was hard to stop by a community center for free resources. Diaz gave Avila her number, offering to help her get what she needed there next time without having to join the crowd inside.

Ashley Jackson of Providence’s Community Public Health Team speaks with Monica Avila in Pacoima last month.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Avila seemed relieved. “Thank you for coming and listening to me,” she said.

The work can be slow going: After stopping at more than 40 homes that morning, Jackson and Diaz had ultimately completed two assessments with residents. They left door hangers about the project on fences, planning to return to people they hadn’t reached.

Romo said she expects that a major challenge will be simply getting people to open their doors. Dedhia said that in Watts, for instance, the community “has been heavily surveyed, but the follow-up isn’t necessarily there all the time.” Another community health worker in Watts recalled that at one home, a man grew angry when the team stopped by, asking them, “Isn’t it obvious what the community needs?”

But Ferrer said the program hinges on the fact that “a lot of people have things that they need help with — and they’re not getting help.”

“We’ll build trust very quickly,” she said, “if we can deliver on that.”

Science

For Oprah Winfrey, a croissant is now just a croissant — not a struggle

Yes, Oprah Winfrey has discussed her weight loss and weight gain and weight in general before — many, many times before. The difference this time around, she says, is how little food noise there is in her daily life, and how little shame. It’s so quiet, in fact, that she can eat a whole croissant and simply acknowledge she had breakfast.

“Food noise,” for those who don’t experience it, is a virtually nonstop mental conversation about food that, according to Tufts Medicine, rarely shuts up and instead drives a person “to eat when they’re not hungry, obsess over meals and feel shame or guilt about their eating habits.”

“This type of obsessive food-related thinking can override hunger cues and lead to patterns of overeating, undereating or emotional eating — especially for people who are overweight,” Tufts said.

Winfrey told People in an exclusive interview published Tuesday that in the past she would have been thinking, “‘How many calories in that croissant? How long is it going to take me to work it off? If I have the croissant, I won’t be able to have dinner.’ I’d still be thinking about that damn croissant!”

What has changed is her acceptance 2½ years ago that she has a disease, obesity, and that this time around there was something not called “willpower” to help her manage it.

The talk show host has been using Mounjaro, one of the GLP-1 drugs, since 2023. The weight-loss version of Mounjaro is Zepbound, like Wegovy is the weight-loss version of Ozempic. Trulicity and Victroza are also GLP-1s, and a pill version of Wegovy was just approved by the FDA.

When she started using the injectable, Winfrey told People she welcomed the arrival of a tool to help her get away from the yo-yo path she’d been on for decades. After understanding the science behind it, she said, she was “absolutely done with the shaming from other people and particularly myself” after so many years of weathering public criticism about her weight.

“I have been blamed and shamed,” she said elsewhere in that 2023 interview, “and I blamed and shamed myself.”

Now, on the eve of 2026, Winfrey says her mental shift is complete. “I came to understand that overeating doesn’t cause obesity. Obesity causes overeating,” she told the outlet. “And that’s the most mind-blowing, freeing thing I’ve experienced as an adult.”

She isn’t even sharing her current weight with the public.

Winfrey did take a break from the medication early in 2024, she said, and started to regain weight despite continuing to work out and eat healthy foods. So for Winfrey the obesity prescription will be renewed for a lifetime. C’est la vie seems to be her attitude.

“I’m not constantly punishing myself,” she said. “I hardly recognize the woman I’ve become. But she’s a happy woman.”

Winfrey has to take a carefully managed magnesium supplement and make sure she drinks enough water, she said. The shots are done weekly, except when she feels like she can go 10 or 12 days. But packing clothes for the Australian leg of her “Enough” book tour was an off-the-rack delight, not a trip down a shame spiral. She’s even totally into regular exercise.

Plus along with the “quiet strength” she has found in the absence of food noise, Winfrey has experienced another cool side effect: She pretty much couldn’t care less about drinking alcohol.

“I was a big fan of tequila. I literally had 17 shots one night,” she told People. “I haven’t had a drink in years. The fact that I no longer even have a desire for it is pretty amazing.”

So back to that croissant. How did she feel after she scarfed it down?

“I felt nothing,” she said. “The only thing I thought was, ‘I need to clean up these crumbs.’”

Science

Owners of mobile home park destroyed in the Palisades fire say they’re finally clearing the debris

Former residents of the Palisades Bowl Mobile Home Estates, a roughly 170-unit mobile home park completely destroyed in the Palisades fire, received a notice Dec. 23 from park owners saying debris removal would start as early as Jan. 2.

The Bowl is the largest of only a handful of properties in the Palisades still littered with debris nearly a year after the fire. It’s left the Bowl’s former residents, who described the park as a “slice of paradise,” stuck in limbo.

The email notice, which was reviewed by The Times, instructed residents to remove any burnt cars from their lots as quickly as possible, since contractors cannot dispose of vehicles without possessing the title. It followed months of near silence from the owners.

“The day before Christmas Eve … it triggers everybody and throws everybody upside down,” said Jon Brown, who lived in the Bowl for 10 years and now helps lead the fight for the residents’ right to return home. “Am I liable if I can’t get this done right now? Between Christmas and New Year’s? It’s just the most obnoxious, disgusting behavior.”

Brown is not optimistic the owners will follow through. “They’ve said things like this before over the years with a bunch of different things,” he said, “and then they find some reason not to do it.”

Earlier this year, the Federal Emergency Management Agency denied requests from the city and the Bowl’s owners to include the park in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cleanup program, which FEMA said was focused on residential lots, not commercial properties. In a letter, FEMA argued it could not trust the owners of the Bowl to preserve the beachfront property as affordable housing.

A tattered flag waves in the wind at Asilomar View Park overlooking the Pacific Palisades Bowl Mobile Estates.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

The Bowl, which began as a Methodist camp in the 1890s, was purchased by Edward Biggs, a Northern California real estate mogul, in 2005 and split between his first and second wives after his death in 2021. The family has a history of failing to perform routine maintenance and seeking to redevelop the park into a more lucrative resort community.

After FEMA’s rejection, the owners failed to meet the City of L.A.’s debris removal deadlines. In October, the city’s Board of Building and Safety Commissioners declared the park a public nuisance alongside seven other properties, giving the city the authority to complete the debris removal itself and charge the owners the bill.

But the city has yet to find funds to front the work, which is expected to cost millions.

On Dec. 10, City Councilmember Traci Park filed a motion that would order the city to come up with a cost estimate for debris removal and identify funding sources within the city. It would also instruct the city attorney’s office to explore using criminal prosecution to address the uncleared properties.

The Department of Building and Safety did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Despite the recent movement on debris removal, residents of the Palisades Bowl still have a long road ahead.

On Wednesday, numerous burnt out vehicles still remained at the Pacific Palisades Bowl Mobile Estates. The owners instructed residents they must get them removed as quickly as possible.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

In mobile home parks, tenants lease their spaces from the landowners but own the homes placed on the land. Before residents can start rebuilding, the Bowl’s owners need to replace or repair the foundations for the homes; fix any damage to the roads, utilities and retaining walls; and rebuild facilities like the community center and pool.

The owners have not responded to multiple requests for comment, but in February, Colby Biggs, Edward Biggs’ grandson, told CalMatters that “If we have to go invest $100 million to rebuild the park and we’re not able to recoup that in some fashion, then it’s not likely we will rebuild the park.”

Mobile home law experts and many residents doubt that the Biggs family would be able to convert the rent-controlled mobile home park into something else under existing law. The most realistic option, should the Biggs decide against rebuilding, would be to sell the park to another owner — or directly to the residents, a course of action the residents have been actively pursuing.

The lack of communication and action from the owners has nonetheless left the Bowl’s eclectic former community of artists, teachers, surfers, first responders and retirees in limbo.

Many are running out of insurance money for temporary housing and remain unsure whether they’ll ever be able to move back.

Science

Video: Drones Detect Virus in Whale Blow in the Arctic

new video loaded: Drones Detect Virus in Whale Blow in the Arctic

By Jamie Leventhal and Alexa Robles-Gil

January 2, 2026

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHamas builds new terror regime in Gaza, recruiting teens amid problematic election

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoGoogle is at last letting users swap out embarrassing Gmail addresses without losing their data

-

Indianapolis, IN1 week ago

Indianapolis, IN1 week agoIndianapolis Colts playoffs: Updated elimination scenario, AFC standings, playoff picture for Week 17

-

Southeast1 week ago

Southeast1 week agoTwo attorneys vanish during Florida fishing trip as ‘heartbroken’ wife pleads for help finding them

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRoads could remain slick, icy Saturday morning in Philadelphia area, tracking another storm on the way

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoMost shocking examples of Chinese espionage uncovered by the US this year: ‘Just the tip of the iceberg’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoMarijuana rescheduling would bring some immediate changes, but others will take time

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPodcast: The 2025 EU-US relationship explained simply