Science

The desperate hours: a pro baseball pitcher's fentanyl overdose

Not many victims of the opioid crisis in America make national headlines. Tyler Skaggs was different.

The 27-year-old was a professional athlete, a pitcher for the Angels, wealthy and famous. On a road trip with the team, he was found in his hotel room. He had choked on his own vomit after consuming a mix of alcohol, oxycodone and fentanyl.

His death on July 1, 2019, sent shock waves through the sports world. A highly publicized criminal investigation not only revealed that Skaggs had secretly used painkillers for years, but also led to the arrest of a team employee accused of providing him with tainted, black market pills.

Five years later, The Times has pored over hundreds of pages of court documents and cellphone records to reconstruct Skaggs’ final hours. Playing cards with teammates on a three-hour flight. Teasing rookies on the bus. Trading affectionate texts with his wife until late at night.

Even the most ordinary details tell an important story, offering an intimate look at an epidemic that has ravaged the country.

Tyler Skaggs pitches against the Oakland Athletics on June 29, 2019, two days before his death.

(Marcio Jose Sanchez / Associated Press)

Skaggs pitches at Angel Stadium against the Oakland A’s and is pulled after surrendering two runs in four-plus innings. CAA agent Nez Balelo texts to commiserate about “the quick hook … after cruising basically through 3 and 4.”

Skaggs is nothing if not dogged. At 6 feet 4 and 225 pounds, he has fought back from a string of serious injuries, refusing to quit, which might help explain his painkiller use. After the game, his mother, Debbie Hetman, a longtime softball coach at Santa Monica High, calls him and his wife.

“I didn’t FaceTime him because I was – we were super busy, so we just talked really quickly,” Hetman later testifies during the team employee’s trial. “I think he was in line at In-N-Out with Carli.”

Mike Trout, wearing Tyler Skaggs’ number in his honor, speaks to Eric Kay in the dugout before a July, 12, 2019, home game against the Seattle Mariners.

( John McCoy / Getty Images)

(Animation by Kelvin Kuo/Los Angeles Times)

Shortly before a 1:07 p.m. game against the A’s, Skaggs receives a text from Eric Kay, the team communications director who for years has allegedly supplied him with “blue boys” — blue, 30-milligram oxycodone pills.

Kay: “Hoe [sic] many?”

Skaggs: “Just a few like 5”

Kay: “Word”

Skaggs: “Don’t need many”

4:25 p.m. Pacific Time

The Angels conclude their four-game home series with a 12-3 loss. It is a get-away day, meaning the team will head directly from the stadium to Long Beach Airport, where a charter plane waits for the start of the road trip.

Skaggs has previously asked his manager’s permission for the players to dress like cowboys for the flight to Texas. Before leaving the stadium, he meets his wife, Carli, so she can snap pictures of him in his black hat, bolo tie and boots.

“When did he buy that outfit?” a prosecutor later asks her during Kay’s trial.

“The day before.”

“Did you help him pick it out?”

“Yes.”

6:11 p.m. PT

Skaggs gathers with teammates on the tarmac beside a United Airlines charter plane for another photo to show off their Western wear. He hitches his thumbs in his belt like a cowboy. Seeing the picture on Instagram, Carli comments: “So cute”

8:07 p.m. PT

(Animation by Kelvin Kuo/Los Angeles Times)

With the Texas Rangers next on the schedule, the flight to Dallas Fort Worth International Airport lasts about three hours. Along the way, Carli texts to ask how things are going.

Skaggs: “Good gambling … losing”

Carli: “Damn babe … How much cool … Lol*”

Skaggs: “200 bucks … I’m winning now”

Carli: “Sweet”

11:06 p.m. Central Time

On the 15-minute ride from the airport to a Dallas-area hotel, Skaggs grabs a microphone at the front of the bus.

“So, he would have been kind of like emceeing, doing the music,” teammate Andrew Heaney later testifies. “You know, we would call younger guys up, ask them, you know, embarrassing questions or make them tell a funny story or whatever it may be, make them sing a song, something like that.”

Throughout the league, Skaggs is known as friendly, funny, eminently likable. Teammate Mike Trout later says: “The energy he brought to a clubhouse … every time you saw him, he’s just picking you up.”

11:25 p.m. CT

The Angels arrive at the Hilton Dallas/Southlake Town Square, where players receive key cards to their rooms and peruse a table of snacks, protein bars and Gatorade. A friend invites Skaggs to go out, but the pitcher remains in his room.

11:47 p.m. CT

(Animation by Kelvin Kuo/Los Angeles Times)

Skaggs texts his room number to Kay.

“469,” he writes, adding: “Come by”

“K,” the communications director responds.

Kay had used opioids enough to know black market oxycodone pills might be laced with dangerous drugs such as fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine. In a jailhouse call recorded after his trial, he denies giving drugs to Skaggs that night, saying he visited the pitcher to talk about something else.

“I guess he hated the rookies or something — and he was one flight up so I flipped my door and went up,” he says.

The hotel does not have security cameras in the hallway, so it is unclear how long Kay spends in room 469.

12:02 a.m. CT

(Animation by Kelvin Kuo/Los Angeles Times)

Skaggs texts with teammate Ty Buttrey. He then trades messages with his wife.

Skaggs: “Miss you babe”

Carli: “Miss u too”

When the two met in 2013, Skaggs reportedly fell hard. Now, they have a house and are thinking about kids. They text continually when the Angels are traveling.

12:42 a.m. CT

“What u Doin,” Carli asks.

No answer. She tries again: “Helllooooo.”

1:09 a.m. CT

It is late in Dallas — two hours later than Los Angeles — and Carli is still waiting for a “goodnight” from her husband. She writes: “U know better than to get drunk and fall asleep without texting me”

Approx. 12:53 p.m. CT

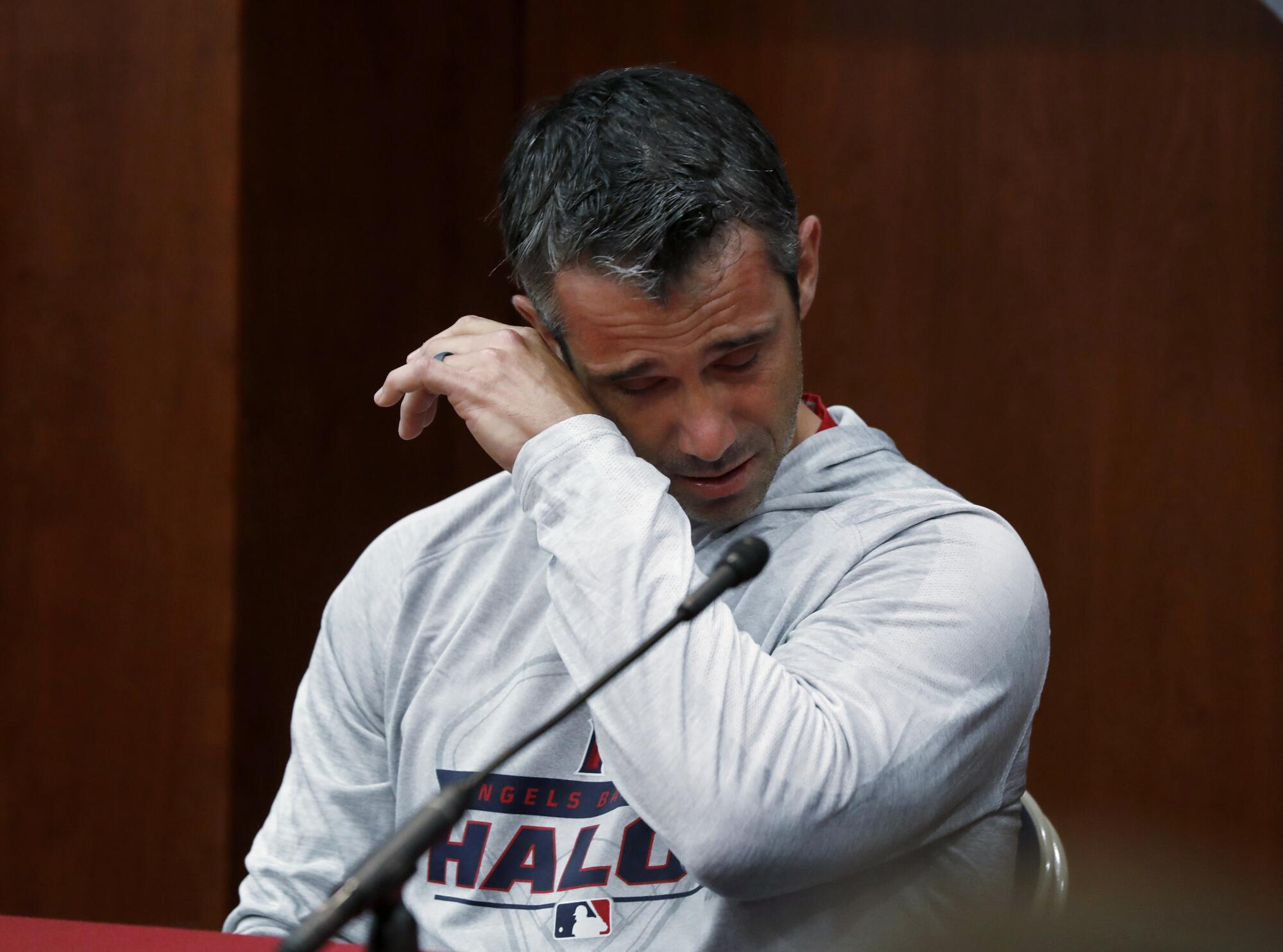

Angels’ Mike Trout, left, embraces Andrew Heaney, who fights back tears as he answers questions about their late friend and teammate Tyler Skaggs.

(Tony Gutierrez / Associated Press)

The night passes, followed by morning, and still no word from Skaggs. Heaney texts him: “Lunch?”

After a few minutes, Heaney stops by room 469. Light shines from under the door; the curtains must be open in there. Nearby, hotel workers are noisily cleaning a carpet. Heaney wonders how anyone could sleep through all this.

When his knock gets no response, he goes back to his room and tries calling Skaggs on the hotel phone.

1:49 p.m. CT

Tom Taylor, the Angels traveling secretary, is having lunch with Kay at a nearby barbecue joint and recalls Carli texting him. Heaney also reaches out to Taylor.

“He hadn’t heard from him either,” Taylor later testifies.

More than 12 hours after Carli’s last exchange with her husband, she messages again: “You have a drinking problem. I’m about to text tom Taylor.”

Carli later insists these words were sent “purely out of anger” with “no truth to it.”

Irritation gives way to another emotion. Carli contacts Skaggs’ mother, Hetman.

“She was really nervous,” Hetman later testifies. “I was really nervous because it was very unusual not to hear back from Tyler. Tyler was very good about returning text messages.” Hetman dials his number, and it sounds as if the call goes directly to voicemail. Her husband, Dan Ramos, sends a text:

“Hi kid. How r u doing. How is life treating u. How is your arm feeling”

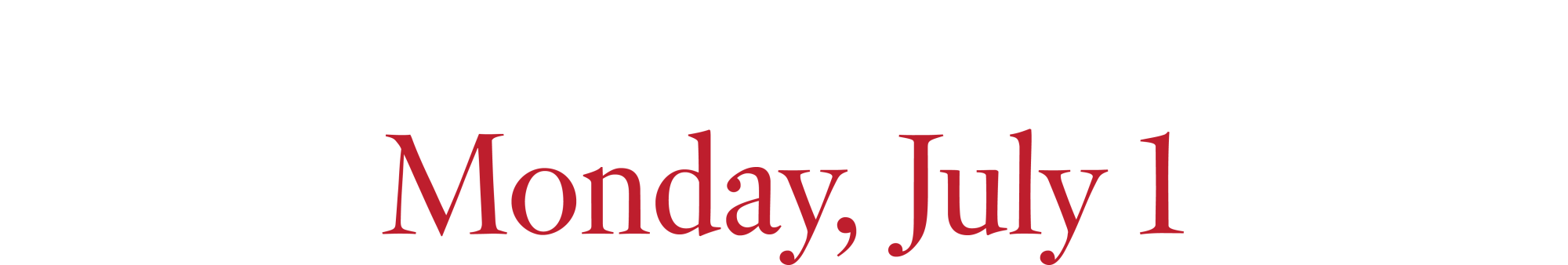

A photo of Tyler Skaggs and his wife, Carli, is displayed outside a memorial service for the Angels pitcher in 2019.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

2:04 p.m. CT

Now Hetman tries texting: “Hey Ty Are you okay today?”

Around the same time, Taylor returns to the hotel and knocks on Skaggs’ door. He then summons Chuck Knight, one of the team’s security men, and they ask hotel management to let them into room 469.

A former Anaheim Police Department officer, Knight enters the room alone, staying less than a minute. Taylor later recalls him emerging with “a shocked-looking face, almost like, it’s not good, what he saw.”

2:16 p.m. CT

Knight calls 911. Asked later about what he encountered in the room, he testifies: “I saw two legs hanging off the end of the bed in a position that I thought was unusual for someone that might be sleeping … I walked closer in an attempt to obtain a pulse. I reached down to grab his wrist and noticed that his skin was very cool to the touch. I did not obtain a pulse.”

Heaney, who is getting messages from Carli, returns to the hallway outside room 469. Taylor tells him: “It’s not good.”

“I knew what was going on, but his wife didn’t,” Heaney later testifies. “And she was texting me, so it was — I just felt like I wanted her to know what was going on.”

He decides not to answer.

A call crackles over the scanner: “Medic 4-1, truck 4-1 respond. Medical emergency, Hilton Southlake Town Square.” The dispatcher adds: “It’s gonna be … a possible death investigation. PD is arriving on scene now.”

A Southlake police officer finds Skaggs’ room looking mostly undisturbed — the bed still made, a backpack and another bag on the couch, unopened beers on the coffee table. There is a white, “almost chalky” substance on the desk. Skaggs’ cellphone lies near his head.

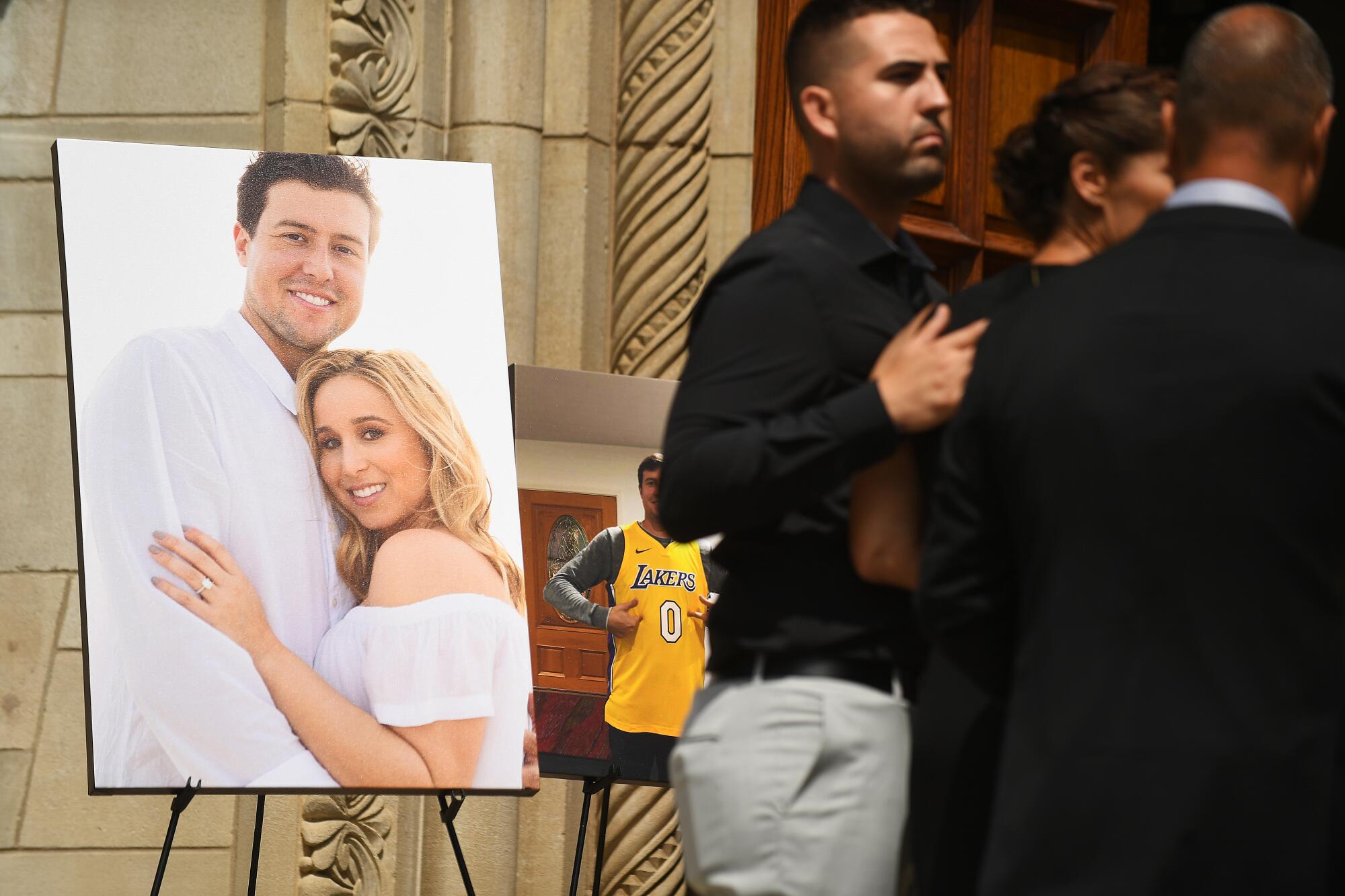

A memorial for Tyler Skaggs on the outfield wall at Angel Stadium.

(Los Angeles Times)

2:23 p.m. CT

Cory Teague, a Southlake Fire Department paramedic, arrives at room 469. His medical supplies include Naloxone, which can be administered to reverse the effects of opioid overdose.

“Did you use it?” a prosecutor later asks at trial.

“No.”

“Why not?”

“The patient had signs incompatible with life, unable to be revived.”

3:05 p.m. CT

Carli’s phone rings as she pulls up to her parents’ house in Santa Monica. It’s Billy Eppler, the Angels’ general manager. “I’ll never, ever forget that call,” she later says. She dials Hetman, who is at her Los Angeles home, and breaks the news. Hetman later recalls “crying and yelling and screaming.”

Buses are scheduled to take the Angels to their evening game. Instead, players and staff are told of Skaggs’ death and shepherded into a hotel banquet room where police take statements.

“The questions that we asked were generic for each player and employee,” Cpl. Delaney Green of the Southlake Police Department later testifies. “And it was along the lines of: When was the last time that you had seen or spoken to Tyler Skaggs? Had you seen him consume any alcohol on the plane? And did you know of any drug use that you were aware of?”

Kay is among those interviewed. He tells police that Skaggs was drinking on the flight to Texas but adds, “I didn’t think he had a lot.” He says he last saw the pitcher when they collected their room keys in the lobby.

3:52 p.m. CT

The Times and other news agencies report Skaggs’ death on social media. Family members call his mother at home. She later testifies that “before I could even talk to anybody, that whole — everything was like blowing up and it was super-crazy.”

4:11 p.m. CT

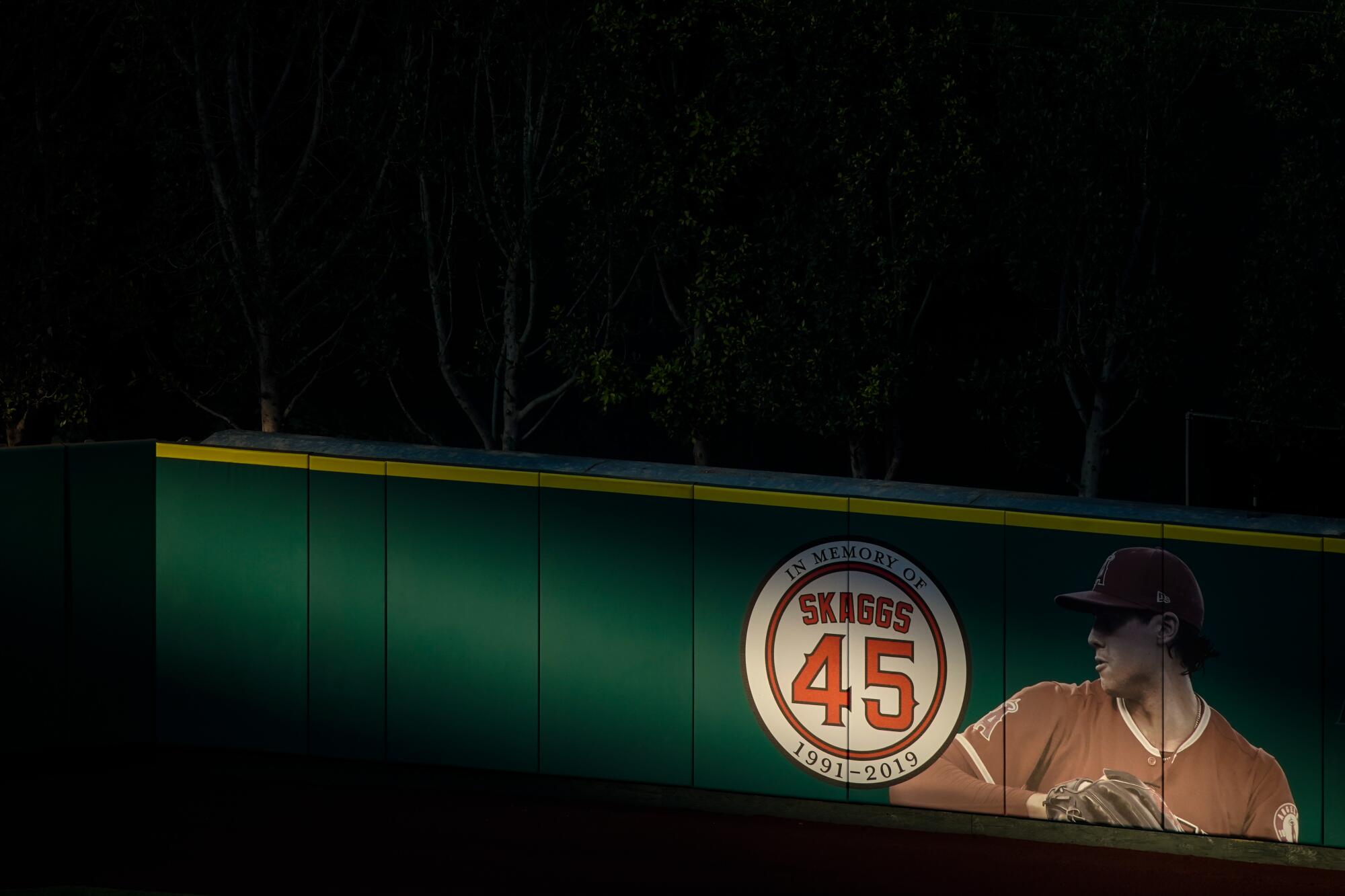

Angels manager Brad Ausmus speaks at a 2019 news conference about Tyler Skaggs’ death.

(Tony Gutierrez / Associated Press)

The Rangers announce the postponement of that night’s game as the Angels switch to another hotel. The team gathers for an emotional meeting. “We were able to talk about Tyler and laugh at some of the stories and some of the goofy things he did, listen to some of his music,” manager Brad Ausmus later says before breaking down.

On social media, players from around the league post messages.

“RIP to my longtime friend and Little League teammate,” then-St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Ryan Sherriff writes. “i love you brotha.”

About 8 p.m. CT

Carli and the Skaggs family board a flight to Texas.

About 10 a.m. CT

Carli and the Skaggs family visit the medical examiner’s office in Fort Worth. She later recalls kissing her husband’s cold lips as he lay on a gurney.

11:10 a.m. CT

The medical examiner begins an autopsy. He will eventually determine that “alcohol, fentanyl and oxycodone intoxication” caused Skaggs to choke on his own vomit.

Later that morning, Carli and the Skaggs family arrive at the Southlake police station to retrieve his luggage, iPad and other belongings.

In words that underscore the anguish of losing a loved one to opioids, Hetman later testifies: “I was angry because I knew that my son loved life and he did not want to die. He did not know that there was poison in that pill that cost him his life.”

About 5:30 p.m. CT

Team officials hold a news conference with Kay standing quietly to the side, hands clasped at his waist. At one point, he appears to take a deep breath, look toward the ceiling and exhale.

7:05 p.m. CT

Teammates place jerseys with Tyler Skaggs’ number 45 on the mound at Angel Stadium at their first home game after his death.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

The game against the Rangers proceeds as scheduled. The ballpark is eerily quiet, with the home team forgoing the usual walk-up music.

The Angels, wearing black No. 45 patches on their jerseys, score early and cruise to a surprising 9-4 victory, but Trout says: “All I was thinking about was Tyler. It was just a different feeling, you know. Just shock.”

Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs died of an overdose in a hotel room on July 1, 2019.

(K.C. Alfred/San Diego Union-Tribune)

Federal prosecutors charged Kay with distribution of a controlled substance resulting in death and conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute controlled substances. A trial began in February 2022.

“This was a case of one, one person who went up to that room on June 30,” a prosecutor said in court. “One person who went into that room and gave Tyler Skaggs fentanyl.”

The jury deliberated less than 90 minutes before returning a guilty verdict on both counts.

At a hearing where the judge sentenced him to 22 years in federal prison, Kay — who didn’t testify during trial — apologized to his family for the “disgrace and embarrassment” he had caused them.

Privately, however, he continued to profess innocence. In a recorded jailhouse call, he told a friend: “The worst thing, though, is that text that he sent me … because I didn’t know what he wanted. I had no idea. In my head, I think he thought I already got more [pills] for him but I told him they were going to be s—.”

By then, the Skaggs family had filed a wrongful-death suit against the Angels. The team has denied wrongdoing, and the case continues.

In the five years since Skaggs died, opioid overdoses — fueled by illicitly manufactured pills — have claimed hundreds of thousands of American lives.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has a 24-hour helpline for individuals and families facing mental and substance abuse disorders. The number is (800) 662-HELP (4357).

Science

Video: Rare Giant Phantom Jelly Spotted in Deep Waters Near Argentina

new video loaded: Rare Giant Phantom Jelly Spotted in Deep Waters Near Argentina

By Meg Felling

February 5, 2026

Hundreds of Sea Turtles Rescued Off the Gulf Coast Due to Freezing Cold

1:27

Four Astronauts Splash Down on Earth After Early Return

1:24

Why Exercise Is the Best Thing for Your Brain Health

1:51

Drones Detect Virus in Whale Blow in the Arctic

0:40

Why Scientists Are Performing Brain Surgery on Monarchs

2:24

Engineer Is First Paraplegic Person in Space

0:19

Today’s Videos

U.S.

Politics

Immigration

NY Region

Science

Business

Culture

Books

Wellness

World

Africa

Americas

Asia

South Asia

Donald Trump

Middle East Crisis

Russia-Ukraine Crisis

Visual Investigations

Opinion Video

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Science

Tuberculosis outbreak reported at Catholic high school in Bay Area. Cases statewide are climbing

Public health officials in Northern California are investigating a tuberculosis outbreak, identifying more than 50 cases at a private Catholic high school and ordering those who are infected to stay home. The outbreak comes as tuberculosis cases have been on the rise statewide since 2023.

The San Francisco Department of Public Health issued a health advisory last week after identifying three active cases and 50 latent cases of tuberculosis at Archbishop Riordan High School in San Francisco. The disease attacks the lungs and remains in the body for years before becoming potentially deadly.

A person with active TB can develop symptoms and is infectious; a person with a latent tuberculosis infection cannot spread the bacteria to others and doesn’t feel sick. However, a person with a latent TB infection is at risk of developing the disease anytime.

The three cases of active TB have been diagnosed at the school since November, according to public health officials. The additional cases of latent TB have been identified in people within the school community.

Archbishop Riordan High School, which recently transitioned from 70 years of exclusively admitting male students to becoming co-ed in 2020, did not immediately respond to the The Times’ request for comment.

School officials told NBC Bay Area news that in-person classes had been canceled and would resume Feb. 9, with hybrid learning in place until Feb. 20. Students who test negative for tuberculosis will be allowed to return to campus even after hybrid learning commences.

Officials with the San Francisco Department of Public Health said the risk to the general population was low. Health officials are currently focused on the high school community.

How serious is a TB diagnosis?

Active TB disease is treatable and curable with appropriate antibiotics if it is identified promptly; some cases require hospitalization. But the percentage of people who have died from the disease is increasing significantly, officials said.

In 2010, 8.4% of Californians with TB died, according to the California Department of Public Health. In 2022, 14% of people in the state with TB died, the highest rate since 1995. Of those who died, 22% died before receiving TB treatment.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that up to 13 million people nationwide live with latent TB.

How does California’s TB rate compare to the country?

Public health officials reported that California’s annual TB incidence rate was 5.4 cases per 100,000 people last year, nearly double the national incidence rate of 3.0 per 100,000 in 2023.

In 2024, 2,109 California residents were reported to have TB compared to 2,114 in 2023 — the latter was about the same as the total number of cases reported in 2019, according to the state Department of Public Health.

The number of TB cases in the state has remained consistent from 2,000 to 2,200 cases since 2012, except during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2022.

California’s high TB rates could be caused by a large portion of the population traveling to areas where TB is endemic, said Dr. Shruti Gohil, associate medical director for UCI Health Epidemiology and Infection Prevention.

Nationally, the rates of TB cases have increased in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic, which “was in some ways anticipated,” said Gohil. The increasing number of TB cases nationwide could be due to a disruption in routine care during the pandemic and a boom in travel post-pandemic.

Routine screening is vital in catching latent TB, which can lie dormant in the body for decades. If the illness is identified, treatment could stop it from becoming active. This type of routine screening wasn’t accessible during the pandemic, when healthcare was limited to emergency or essential visits only, Gohil said.

When pandemic restrictions on travel were lifted, people started to travel again and visit areas where TB is endemic, including Asia, Europe and South America, she said.

To address the uptick in cases and suppress spread, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 2132 into law in 2024, which requires adult patients receiving primary care services to be offered tuberculosis screening if risk factors are identified. The law went into effect in 2025.

What is TB?

In the United States, tuberculosis is caused by a germ called Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which primarily affects the lungs and can impact other parts of the body such as the brain, kidneys and spine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. If not treated properly, TB can be fatal.

TB is spread through the air when an infected person speaks, coughs or sings and a nearby person breathes in the germs.

When a person breathes in the TB germs, they settle in the lungs and can spread through the blood to other parts of the body.

The symptoms of active TB include:

- A cough that lasts three weeks or longer

- Chest pain

- Coughing up blood or phlegm

- Weakness or fatigue

- Weight loss

- Loss of appetite

- Chills

- Fever

- Night sweats

Generally, who is at risk of contracting TB?

Those at higher risk of contracting TB are people who have traveled outside the United States to places where TB rates are high including Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe and Latin America.

A person has an increased risk of getting TB if they live or work in such locations as hospitals, homeless shelters, correctional facilities and nursing homes, according to the CDC.

People with weakened immune systems caused by health conditions that include HIV infection, diabetes, silicosis and severe kidney disease have a higher risk of getting TB.

Others at higher risk of contracting the disease include babies and young children.

Science

Contributor: Animal testing slows medical progress. It wastes money. It’s wrong

I am living with ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, often called Lou Gehrig’s disease. The average survival time after diagnosis is two to five years. I’m in year two.

When you have a disease like ALS, you learn how slowly medical research moves, and how often it fails the people it is supposed to save. You also learn how precious time is.

For decades, the dominant pathway for developing new drugs has relied on animal testing. Most of us grew up believing this was unavoidable: that laboratories full of caged animals were simply the price of medical progress. But experts have known for a long time that data tell a very different story.

The Los Angeles Times reported in 2017: “Roughly 90% of drugs that succeed in animal tests ultimately fail in people, after hundreds of millions of dollars have already been spent.”

The Times editorial board summed it up in 2018: “Animal experiments are expensive, slow and frequently misleading — a major reason why so many drugs that appear promising in animals fail in human trials.”

Then there’s the ethical cost — confining, sickening and killing millions of animals each year for a system that fails 9 times out of 10. As Jane Goodall put it, “We have the choice to use alternatives to animal testing that are not cruel, not unethical, and often more effective.”

Despite overwhelming evidence and well-reasoned arguments against animal-based pipelines, they remain central to U.S. medical research. Funding agencies, academic medical centers, government labs, pharmaceutical companies and even professional societies have been painfully slow to move toward human- and technology-based approaches.

Yet medical journals are filled with successes involving organoids (mini-organs grown in a lab), induced pluripotent stem cells, organ-on-a-chip systems (tiny devices with human cells inside), AI-driven modeling and 3D-bioprinted human tissues. These tools are already transforming how we understand disease.

In ALS research, induced pluripotent stem cells have allowed scientists to grow motor neurons in a dish, using cells derived from actual patients. Researchers have learned how ALS-linked mutations damage those neurons, identified drug candidates that never appeared in animal models and even created personalized “test beds” for individual patients’ cells.

Human-centric pipelines can be dramatically faster. Some are reported to be up to 10 times quicker than animal-based approaches. AI-driven human biology simulations and digital “twins” can test thousands of drug candidates in silico, with a simulation. Some models achieve results hundreds, even thousands, of times faster than conventional animal testing.

For the 30 million Americans living with chronic or fatal diseases, these advances are tantalizing glimpses of a future in which we might not have to suffer and die while waiting for systems that don’t work.

So why aren’t these tools delivering drugs and therapies at scale right now?

The answer is institutional resistance, a force so powerful it can feel almost god-like. As Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist Kathleen Parker wrote in 2021, drug companies and the scientific community “likely will fight … just as they have in past years, if only because they don’t want to change how they do business.”

She reminds us that we’ve seen this before. During the AIDS crisis, activists pushed regulators to move promising drugs rapidly into human testing. Those efforts helped transform AIDS from a death sentence into a chronic condition. We also saw human-centered pipelines deliver COVID vaccines in a matter of months.

Which brings me, surprisingly, to Robert F. Kennedy Jr. In December, Kennedy told Fox News that leaders across the Department of Health and Human Services are “deeply committed to ending animal experimentation.” A department spokesperson later confirmed to CBS News that the agency is “prioritizing human-based research.”

Kennedy is right.

His directive to wind down animal testing is not anti-science. It is pro-patient, pro-ethics and pro-progress. For people like me, living on borrowed time, it is not just good policy, it is hope — and a potential lifeline.

The pressure to end animal testing and let humans step up isn’t new. But it’s getting new traction. The actor Eric Dane, profiled about his personal fight with ALS, speaks for many of us when he expresses his wish to contribute as a test subject: “Not to be overly morbid, but you know, if I’m going out, I’m gonna go out helping somebody.”

If I’m going out, I’d like to go out helping somebody, too.

Kevin J. Morrison is a San Francisco-based writer and ALS activist.

-

Indiana4 days ago

Indiana4 days ago13-year-old rider dies following incident at northwest Indiana BMX park

-

Massachusetts5 days ago

Massachusetts5 days agoTV star fisherman, crew all presumed dead after boat sinks off Massachusetts coast

-

Tennessee6 days ago

Tennessee6 days agoUPDATE: Ohio woman charged in shooting death of West TN deputy

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoVikram Prabhu’s Sirai Telugu Dubbed OTT Movie Review and Rating

-

Indiana4 days ago

Indiana4 days ago13-year-old boy dies in BMX accident, officials, Steel Wheels BMX says

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoVirginia Democrats seek dozens of new tax hikes, including on dog walking and dry cleaning

-

Austin, TX7 days ago

TEA is on board with almost all of Austin ISD’s turnaround plans

-

Texas5 days ago

Texas5 days agoLive results: Texas state Senate runoff