Science

National suicide prevention hotline plans to stop offering LGBTQ+ youth counseling. Queer advocates in L.A. wonder what's next

Amy Kane was filled with dread when she heard that the national suicide prevention lifeline would stop offering specialized crisis intervention to young LGBTQ+ Americans and end its partnership with the West Hollywood-based Trevor Project.

With the service set to end July 17, Kane, a therapist who identifies as lesbian, believes the Trump administration is sending a clear message to queer Americans: “We don’t care whether you live or die.”

Since it launched in 2022, more than 1.3 million queer young Americans struggling with a mental health crisis have dialed the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, which gave them the option to press “3” to connect with a specialist trained to address their unique life experiences. As the largest of seven LGBTQ+ contractors, the Trevor Project alone handles about half of all volume from queer callers to the 988 line.

The government’s decision is yet another broadside from an administration whose actions have left queer public health advocates and providers reeling, including at the Los Angeles LGBTQ Center, where Kane serves as director of mental health services.

Under pressure from the Trump administration, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles sent letters to families in early June saying it planned to suspend its healthcare program for transgender children and young adults in late July. The LGBTQ Center and other groups have demanded that the hospital reconsider.

Around the same time came the news about the 988 line and the Trevor Project, a nonprofit founded in 1998 by the makers of the Academy Award-winning short film “Trevor” — about a teen who attempts suicide — to address the absence of a major prevention network tailored to the needs of queer youth.

“So much has been thrown our way in the last five months,” Kane said. “It’s across the board. It’s not just mental health. We see what’s happening with gender-affirming care, dramatic cuts in research for HIV and STIs. … What’s next?”

Given L.A.’s status as a haven for LGBTQ+ people — the first permitted Pride parade took place in Hollywood in 1970 — Kane wonders whether the recent moves are an attempt to intimidate and punish Californians for being so welcoming.

Terra Russell-Slavin, left, denounced cuts to LGBT health funding as public health care becoming political as Rep. Laura Friedman, center, and Craig Thompson, CEO of the David Geffen Health Center look on at the APLA Health, Michael Gottlieb Health Center in West Hollywood last month.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The threats aren’t just coming from Washington. Kane said that she and other leaders had to lobby state legislators recently to preserve funding for a queer women’s preventive-healthcare program offered through the L.A. LGBTQ Center that was to be revoked due to a state budget shortfall. For now, the program has been given a temporary reprieve.

“It used to be this idea of, ‘Oh yeah, that’s in the red states, but I’m safe in California’ — it doesn’t feel that way anymore,” Kane said.

Staff members at the Trevor Project are scrambling to figure out how to save the jobs of about 200 counselors who are paid through the federal contract, including raising private funds to make up for the unexpected shortfall, said Mark Henson, interim vice president of advocacy and government affairs. The news couldn’t come at a worse time, given that calls nationwide are on pace to top 700,000 in 2025. That’s up from 600,000 in 2024, a spokesperson said, citing metrics from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Another 100 crisis counselors are employed and paid separately by the Trevor Project itself. They will continue taking calls through the project’s own 24/7, free crisis line, one of several options that local LGBTQ+ organizations offer. Los Angeles County’s Alternative Crisis Response has a 24/7 helpline at (800) 854-7771 that also provides culturally sensitive support services.

But Alex Boyd, the Trevor Project’s director of crisis intervention, said he isn’t sure how his organization can make up for the loss of the nationwide visibility and federal support that the 988 partnership affords them.

LGBTQ+ young people are more than four times as likely to attempt suicide than their peers, according to the Trevor Project. Its 2024 survey found that in California, 35% of LGBTQ+ young people seriously considered taking their own lives and that 11% of respondents had attempted suicide in the previous year.

In defending the decision to stop working with the Trevor Project at a House budget hearing in May, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said that while Trump supports the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in general, “We don’t want to isolate different demographics and polarize our country.”

The big question, Boyd said, is will young LGBTQ+ Americans who already feel shunned or misunderstood still trust a suicide prevention line that no longer offers counselors they can easily relate to?

A one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work when it comes to people in emotional and mental distress, Boyd said.

He fears the worst.

“The fact that such a significant amount of our capacity for impact has now been stripped away — there is no operational way in order to navigate through a moment like this that doesn’t result, in at least the short term, in a loss of life.”

Counselors at the Trevor Project hear the anguish over the anti-LGBTQ+ backlash in the voices of young callers seeking help through the lifeline, Boyd said. “The statements we are hearing are: ‘Our government doesn’t support me. The government is actively erasing my experience from the national conversation.’ ”

“Increasingly, the biggest thread that we see from young people reaching out to us is this idea that it is already difficult to be a young person in the world — this is another layer that we’re adding onto children’s lives,” Boyd said. “They’re coming to us saying they’re not sure how they’re going to be able to navigate through more years of this before they get some level of autonomy and agency and find some sense of safety.”

Along with a host of executive actions signed by the president, thousands of bills targeting the LGBTQ+ community have been introduced in state legislatures, in cities and in school districts in California and around the country, including calls to ban books that mention same-sex relationships and gender identity, remove the Pride flag from government buildings and kick trans athletes off of sports teams.

Adding to the strain on the queer community, Trump’s self-described “Big Beautiful Bill,” recently passed in both houses in Congress, cuts public health funding for low-income Americans who receive Medicaid. LGBTQ+ Americans are twice as likely to rely on Medicaid to receive their health care than other Americans, said Alexandra Curd, a staff policy attorney at the national advocacy group Lambda Legal.

Over 40% of nonelderly U.S. adults living with HIV depend on the federal program for their healthcare needs compared to 15% for the general population, according to KFF. Many recipients rely nonprofit organizations funded by federal grants to get HIV and STI screenings and receive HIV prevention medications such as PREP and PEP, Curd said.

Because of the Medicaid cuts and the prospect of increased difficulty in accessing preventive care and emotional support, “We’re going to possibly be seeing rising infections rates for HIV,” she said.

Curd said a recent spike in HIV rates among Latino men could only worsen. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officials have cited a lack of adequate funding, racial bias, language barriers and mistrust of the medical system among the reasons that gay and bisexual Latino men account for a disproportionate percentage of new HIV cases.

Lambda Legal’s help desk has already received more requests for assistance with health care, employment and housing discrimination in the first half of 2025 than in all of 2024, with the most pressing need coming from trans and nonbinary callers.

One piece of good news for L.A. came recently when Rep. Laura Friedman (D–West Hollywood) announced that the Trump administration had restored more than $19 million in federal grants for HIV and STI prevention and tracking that were earmarked for the L.A. County Department of Public Health but slashed by the CDC. Friedman said she and others spoke out against the cut were able to secure an extra $338,019 in federal funding for the new fiscal year starting June 1.

But it’s hard for healthcare organizations to celebrate given that vital funds for mental health and HIV programs were targeted in the first place.

Manny Zermeño, a behavioral health specialist at the Long Beach office of another queer community service organization, APLA Health, senses the distress in his clients. “There is fear, sadness and also with those feelings, it’s natural to have some anger and confusion,” Zermeño said.

The L.A.-based nonprofit focuses on providing free and affordable dental, medical, counseling and other services for queer people 18 and over. It was founded in 1982 as AIDS Project Los Angeles. Back then, a small team of volunteers worked a telephone hotline in the closet of the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbians Community Service Center, fielding calls from panicked residents seeking answers about what was then a fatal disease for which there was no treatment.

The organization operated the first dental clinic in the U.S. catering to AIDS patients out of a trailer in West Hollywood. After movie star Rock Hudson announced he had AIDS in 1985, the organization galvanized support among Angelenos by hosting the first-ever AIDS Walk fundraiser at Paramount Studios, according to its website.

Kane and leaders of other community organizations in L.A. said they would rally once again, this time to assist the Trevor Project.

“All of us who have boots on the ground — you’ll literally have to drag us out by our ankles in order to not provide care to our community,” Kane said. “I don’t believe that queer kids will not have access to resources, because we won’t allow it.”

Science

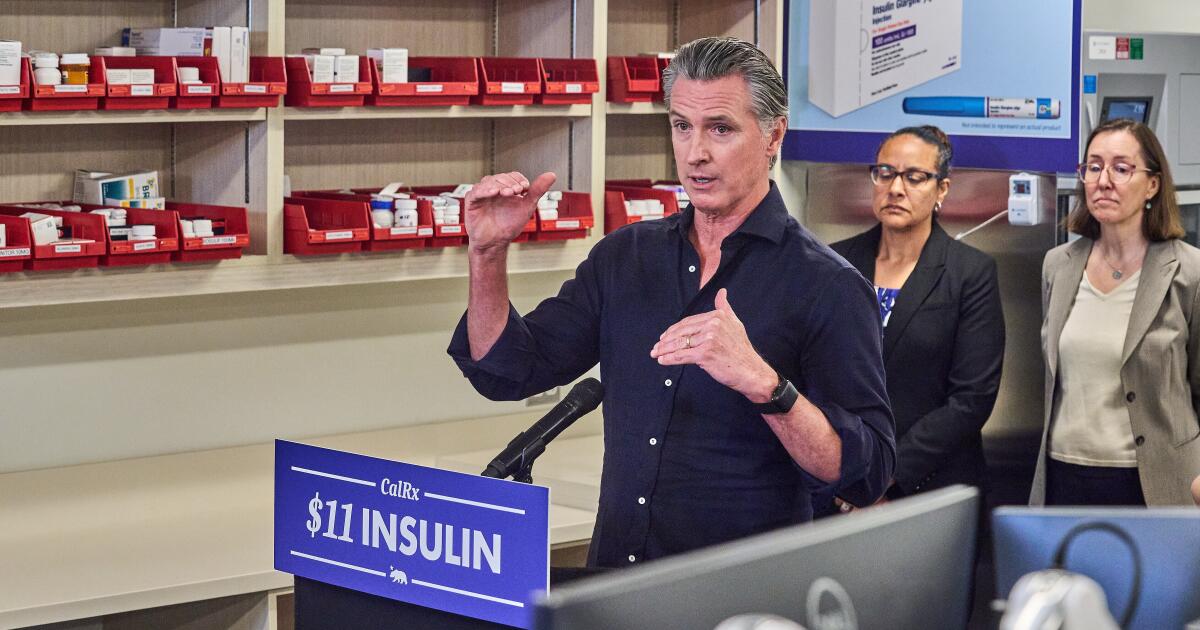

Newsom’s fight with Trump and RFK Jr. on public health

SACRAMENTO — California Gov. Gavin Newsom has positioned himself as a national public health leader by staking out science-backed policies in contrast with the Trump administration.

After Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Susan Monarez for refusing what her lawyers called “the dangerous politicization of science,” Newsom hired her to help modernize California’s public health system. He also gave a job to Debra Houry, the agency’s former chief science and medical officer, who had resigned in protest hours after Monarez’s firing.

Newsom also teamed up with fellow Democratic governors Tina Kotek of Oregon, Bob Ferguson of Washington and Josh Green of Hawaii to form the West Coast Health Alliance, a regional public health agency, whose guidance the governors said would “uphold scientific integrity in public health as Trump destroys” the CDC’s credibility. Newsom argued establishing the independent alliance was vital as Kennedy leads the Trump administration’s rollback of national vaccine recommendations.

More recently, California became the first state to join a global outbreak response network coordinated by the World Health Organization, followed by Illinois and New York. Colorado and Wisconsin signaled they plan to join. They did so after President Trump officially withdrew the United States from the agency on the grounds that it had “strayed from its core mission and has acted contrary to the U.S. interests in protecting the U.S. public on multiple occasions.” Newsom said joining the WHO-led consortium would enable California to respond faster to communicable disease outbreaks and other public health threats.

Although other Democratic governors and public health leaders have openly criticized the federal government, few have been as outspoken as Newsom, who is considering a run for president in 2028 and is in his second and final term as governor. Members of the scientific community have praised his effort to build a public health bulwark against the Trump administration’s slashing of funding and scaling back of vaccine recommendations.

What Newsom is doing “is a great idea,” said Paul Offit, an outspoken critic of Kennedy and a vaccine expert who formerly served on the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory committee but was removed under Trump in 2025.

“Public health has been turned on its head,” Offit said. “We have an anti-vaccine activist and science denialist as the head of U.S. Health and Human Services. It’s dangerous.”

The White House did not respond to questions about Newsom’s stance and Health and Human Services declined requests to interview Kennedy. Instead, federal health officials criticized Democrats broadly, arguing that blue states are participating in fraud and mismanagement of federal funds in public health programs.

Health and Human Services spokesperson Emily Hilliard said the administration is going after “Democrat-run states that pushed unscientific lockdowns, toddler mask mandates, and draconian vaccine passports during the COVID era.” She said those moves have “completely eroded the American people’s trust in public health agencies.”

Public health guided by science

Since Trump returned to office, Newsom has criticized the president and his administration for engineering policies that he sees as an affront to public health and safety, labeling federal leaders as “extremists” trying to “weaponize the CDC and spread misinformation.” He has excoriated federal officials for erroneously linking vaccines to autism, warning that the administration is endangering the lives of infants and young children in scaling back childhood vaccine recommendations. And he argued that the White House is unleashing “chaos” on America’s public health system in backing out of the WHO.

The governor declined an interview request, but Newsom spokesperson Marissa Saldivar said it’s a priority of the governor “to protect public health and provide communities with guidance rooted in science and evidence, not politics and conspiracies.”

The Trump administration’s moves have triggered financial uncertainty that local officials said has reduced morale within public health departments and left states unprepared for disease outbreaks and prevention efforts. The White House last year proposed cutting Health and Human Services spending by $33 billion, including $3.6 billion from the CDC. Congress largely rejected those cuts last month, although funding for programs focusing on social drivers of health, such as access to food, housing and education, were axed.

The Trump administration announced that it would claw back more than $600 million in public health funds from California, Colorado, Illinois and Minnesota, arguing that the Democratic-led states were funding “woke” initiatives that didn’t reflect White House priorities. Within days, the states sued and a judge temporarily blocked the cut.

“They keep suddenly canceling grants and then it gets overturned in court,” said Kat DeBurgh, executive director of the Health Officers Assn. of California. “A lot of the damage is already done because counties already stopped doing the work.”

Federal funding has accounted for more than half of state and local health department budgets nationwide, with money going toward fighting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, preventing chronic diseases, and boosting public health preparedness and communicable disease response, according to a 2025 analysis by KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

Federal funds account for $2.4 billion of California’s $5.3-billion public health budget, making it difficult for Newsom and state lawmakers to backfill potential cuts. That money helps fund state operations and is vital for local health departments.

Funding cuts hurt all

Los Angeles County public health director Barbara Ferrer said if the federal government is allowed to cut that $600 million, the county of nearly 10 million residents would lose an estimated $84 million over the next two years, in addition to other grants for prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Ferrer said the county depends on nearly $1 billion in federal funding annually to track and prevent communicable diseases and combat chronic health conditions, including diabetes and high blood pressure. Already, the county has announced the closure of seven public health clinics that provided vaccinations and disease testing, largely because of funding losses tied to federal grant cuts.

“It’s an ill-informed strategy,” Ferrer said. “Public health doesn’t care whether your political affiliation is Republican or Democrat. It doesn’t care about your immigration status or sexual orientation. Public health has to be available for everyone.”

A single case of measles requires public health workers to track down 200 potential contacts, Ferrer said.

The U.S. eliminated measles in 2000 but is close to losing that status as a result of vaccine skepticism and misinformation spread by vaccine critics. The U.S. had 2,281 confirmed cases last year, the most since 1991, with 93% in people who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown. This year, the highly contagious disease has been reported at schools, airports and Disneyland.

Public health officials hope the West Coast Health Alliance can help counteract Trump by building trust through evidence-based public health guidance.

“What we’re seeing from the federal government is partisan politics at its worst and retaliation for policy differences, and it puts at extraordinary risk the health and well-being of the American people,” said Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Assn., a coalition of public health professionals.

Robust vaccine schedule

Erica Pan, California’s top public health officer and director of the state Department of Public Health, said the West Coast Health Alliance is defending science by recommending a more robust vaccine schedule than the federal government. California is part of a coalition suing the Trump administration over its decision to rescind recommendations for seven childhood vaccines, including for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, influenza and COVID-19.

Pan expressed deep concern about the state of public health, particularly the uptick in measles. “We’re sliding backwards,” Pan said of immunizations.

Sarah Kemble, Hawaii’s state epidemiologist, said Hawaii joined the alliance after hearing from pro-vaccine residents who wanted assurance that they would have access to vaccines.

“We were getting a lot of questions and anxiety from people who did understand science-based recommendations but were wondering, ‘Am I still going to be able to go get my shot?’” Kemble said.

Other states led mostly by Democrats have also formed alliances, with Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and several other East Coast states banding together to create the Northeast Public Health Collaborative.

Hilliard, of Health and Human Services, said that even as Democratic governors establish vaccine advisory coalitions, the federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices “remains the scientific body guiding immunization recommendations in this country, and HHS will ensure policy is based on rigorous evidence and gold standard science, not the failed politics of the pandemic.”

Influencing red states

Newsom, for his part, has approved a recurring annual infusion of nearly $300 million to support the state Department of Public Health, as well as the 61 local public health agencies across California, and last year signed a bill authorizing the state to issue its own immunization guidance. It requires health insurers in California to provide patient coverage for vaccinations the state recommends even if the federal government doesn’t.

Jeffrey Singer, a doctor and senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, said decentralization can be beneficial. That’s because local media campaigns that reflect different political ideologies and community priorities may have a better chance of influencing the public.

A KFF analysis found some red states are joining blue states in decoupling their vaccine recommendations from the federal government’s. Singer said some doctors in his home state of Arizona are looking to more liberal California for vaccine recommendations.

“Science is never settled, and there are a lot of areas of this country where there are differences of opinion,” Singer said. “This can help us challenge our assumptions and learn.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.

Science

How Rising Home Insurance Costs Are Linked to Credit Scores

Two friends bought nearly identical homes last year, in the same northern Minnesota neighborhood, for the same price.

But Tara Novak pays more than twice as much for home insurance as Petra Rodriguez. The only difference? Ms. Novak has a lower credit score.

Across the country, people with weaker credit histories are paying far more for home insurance than owners with spotless records.

Where the home insurance rate gap between “fair” and “excellent” credit is higher

Home insurance premiums have risen rapidly in recent years, fueled by climate change, building costs and inflation. The price shock has rippled into the real estate market, dragging down home prices in areas vulnerable to disasters and leading insurers to abandon homeowners in risky places.

But these dynamics obscure another problem: The home insurance market has cleaved in two along a boundary defined more by a customer’s personal history than by the risk of a disaster hitting their home.

Americans with weaker credit histories, usually from missed payments or high amounts of debt, now pay significantly more for insurance, regardless of where they live, two new studies have found. While those with poor credit histories often can’t purchase homes at all, people with “fair” scores, which range from around 580 to 669, are paying twice as much in some places as people with “excellent” scores of about 800 or higher. And the gap is growing.

Insurers use a metric based on credit history known as an insurance score to set rates, and the figure tracks closely with a customer’s credit score.

The penalty for having a “fair” credit history versus an “excellent” one

States with the biggest pricing gaps

That can mean owners of identical homes, like Ms. Novak and Ms. Rodriguez, pay wildly different rates to insure them. For most people, it’s now just as expensive to have a credit score of “fair” as it is to live in an area likely to experience a disaster like a hurricane or wildfire. About 29 percent of consumers have credit scores that are categorized as “fair” or “poor.”

“There’s so many reasons people have bad credit,” Ms. Novak said. “It’s not like I’ve ever not paid a bill on time. I’m a stickler on my bills, I’m a stickler on my rent, never been late. This is not fair.”

“The choice to use credit scores in pricing means that those lower-credit home owners in risky areas are effectively subsidizing more affluent high-credit homeowners who also live in risky areas,” said Nick Graetz, assistant professor of sociology at the University for Minnesota, who wrote one of the recent papers. “So in a lot of ways, you can keep your insurance price down if you’re high income, high credit — even if you live on the coast of Florida.”

A handful of states have banned insurers from using credit data because of concerns about fairness and the potential for discrimination against low-income people and people of color, but the majority allow it.

For those with both weaker credit and high disaster risk, the combination can set them up for a downward spiral: disasters tend to be followed by decreases in credit scores as people use credit cards and bank loans to recover. That can lead to higher insurance rates, pushing monthly housing costs further out of reach.

“When a disaster hits, there’s a loss of income that occurs, and then that can impact someone’s credit score because they can’t pay their debt, they can’t pay their rent, they can’t pay their mortgage,” said Lance Triggs, executive vice president at Operation HOPE, a financial literacy nonprofit. “And now they’re faced with higher insurance premiums post-disaster.”

A working paper released today by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that homeowners with the lowest credit scores paid, on average, $550 more in 2024 for home insurance than those with the highest scores.

The findings broadly track with data from Quadrant Information Services analyzed by The New York Times, which found that, on average, lower credit scores meant higher premiums across every state that allowed the practice. Dr. Graetz used the same data set for his research, which he did in collaboration with the Consumer Federation of America and the Climate and Community Institute.

When a windstorm last year hit the home of Audrey Thayer, a city council member in Bemidji, Minn., it ripped the siding off her house and stripped shingles from her roof.

Ms. Thayer’s insurance did not cover all the damage. As she fought her insurer for more money, she opened new credit cards and bank loans to repair her home. Her credit score dropped as she tried to find a new insurance plan.

Ms. Thayer, a member of the White Earth Nation, said she was not aware that her credit score could affect her home insurance rates, even though she teaches about credit ratings at a nearby tribal college. “Most of the folks here do not have good credit,” said Ms. Thayer, whose community is one of the poorest in the state. “I did not know what a credit score was until I was 35 or so.”

In Texas, the advocacy group Texas Appleseed found that some insurers charge people with poor credit up to 12 times as much as people with excellent credit for certain policies, said Ann Baddour, the director of the nonprofit’s Fair Financial Services Project.

Higher costs have serious implications for low-income homeowners who live in the path of hurricanes, said Nadia Erosa, the operations manager at Come Dream Come Build, a nonprofit community housing development organization. After the Brownsville, Texas, region saw intense flooding last spring, some residents turned to companies offering high-interest loans to fund repairs, she said, raising the risk of the disaster-credit spiral.

“Delinquencies are going up because people cannot afford their payment,” she said.

The price of risk

Before they can get a mortgage, homebuyers are usually required by lenders to purchase home insurance.

“Households with insurance have fewer financial burdens, fewer unmet needs, they recover faster, they’re more likely to rebuild,” said Carolyn Kousky, an economist and founder of Insurance for Good, a nonprofit that focuses on finding new approaches to risk management. “Yet the people who need insurance the most are the least able to afford it.”

Insurance companies consider a variety of factors when setting the premium for a property. They might examine the age of the roof, or the area’s vulnerability to hurricanes or wildfires. They factor in how much it would cost to rebuild the house if it were damaged.

Insurers have argued that credit history is also worth considering because people with low scores tend to file more claims than those with excellent scores, an assertion that is backed up by the working paper published in the National Bureau of Economic Research today. This likely happens because people with weaker credit histories tend to have less income, and when their home is damaged, they file insurance claims for smaller fixes that a wealthier homeowner might pay for out of pocket.

Paul Tetrault, senior director at the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, a trade organization, said credit scores are a valid way to price premiums.

But others argue that using credit information to price insurance doesn’t make sense.

Because a homeowner pays for insurance upfront, “it’s not like you’re really extending a loan to the customer where you would be worried about the risk of repayment,” Ms. Kousky said. She points out that insurance companies can opt not to renew a homeowner’s policy if they believe it is too risky — a tactic they have been using with increasing frequency.

The NBER analysis found that homeowners who want to pay less for insurance should pay off debt to raise their credit score rather than replace roofs and make other improvements to avoid damage when disaster strikes.

Others believe that even if credit scores are accurate predictors of future claims, they shouldn’t be used to set premiums because that can perpetuate or worsen disparities. For example, people in their mid-20s who are Black, low-income, or grow up in impoverished regions have significantly lower credit scores than their peers, a July working paper from Opportunity Insights, a not-for-profit organization at Harvard University, found.

“When the government and the financial system mandate that we buy a product, there’s a special obligation to make sure the pricing is fair,” said Doug Heller, director of insurance at the Consumer Federation. “To me that is an absolutely solid reason, just like we don’t allow pricing based on race or income or ethnicity or religion.”

A natural experiment

A handful of states, including California and Massachusetts, have banned or limited the use of credit scores in setting home insurance premiums, despite opposition from the insurance industry.

In Nevada, where a temporary pandemic-related rule prevented insurers from using credit history to increase premiums for existing customers from 2020 to 2024, companies refunded approximately $27 million to nearly 200,000 policyholders, said Drew Pearson, a spokesman for the Nevada Division of Insurance.

Perhaps the clearest example of the effects of these bans comes from Washington State, which banned the use of credit information in setting home insurance premiums starting in June 2021. The rule immediately faced legal challenges, and was in effect for just a few months until it was overturned in court.

But the episode allowed researchers to evaluate the effect of credit factors on insurance premiums. When the rule took effect, people with the lowest credit scores saw a decrease in premiums of about $175 annually while those with the highest scores saw an increase of about $100, the NBER analysis found.

“We could see the dynamics of insurance pricing for the same households over time,” said Benjamin Keys, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, who co-authored the paper.

What homeowners paid before and after a ban on credit-based pricing in Washington State

Values compared with premiums paid by homeowners with “medium” credit scores (717 to 756)

In Minnesota, where Tara Novak, Petra Rodriguez and Audrey Thayer live, a state task force looked at ways to lower insurance costs for residents. It recently considered a ban or limit on the use of credit scores to set rates, but did not move forward with a recommendation.

Ms. Rodriguez said she doesn’t think it’s fair that her friend Ms. Novak should have to pay so much more for insurance to live in an identical house.

A credit score doesn’t capture anything about a person’s habits, or what they’re like as a tenant, or even years of on-time rent payments, she said. “It’s not who you are,” she said.

Methodology

Home insurance policy rates were supplied by Quadrant Information Services, an insurance data solutions company. The rates shown are representative of publicly sourced filings and should not be interpreted as bindable quotes. Actual individual premiums may vary.

‘States with the biggest pricing gaps’Rates shown are based on a home insurance policy with $400,000 of dwelling coverage and a $100,000 liability limit on a new home, for a homeowner age 50 or younger. Rates are averaged for all the individual company filings represented in the sample, which add up to a majority of the market share in each state but do not cover all active insurers in the state. Rates are also averaged to the state level from zip code level data.

‘The credit penalty in each state’Each insurance company incorporates credit history information differently, often using proprietary methods, so the scores do not map directly to FICO credit scores.

‘What homeowners paid before and after a ban on credit-based pricing in Washington State’Data shown are based on observations of real home insurance policies and homeowner credit scores from ICE McDash analyzed by the researchers of Blonz, Hossain, Keys, Mulder and Weill (2026). The price comparisons across credit score tiers controlled for variance in disaster risk, insurance policy characteristics, geography, and other year to year fluctuations.

Science

Earth is warming faster than previously estimated, new study shows

Planetary warming has significantly accelerated over the past 10 years, with temperatures rising at a higher rate since 2015 than in any previous decade on record, a new study showed.

The Earth warmed around 0.35 degrees Celsius in the decade to 2025, compared to just under 0.2C per decade on average between 1970 and 2015, according to a paper published on Friday in the scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters. This is the first statistically significant evidence of an acceleration of global warming, the authors said.

The past three years have been the hottest on record, compared to the average before the Industrial Revolution. In 2024, warming went past 1.5C, the lower limit set by the Paris Agreement. That target refers to temperature increases over 20 years, but breaching it for one year shows efforts to slow down climate change have been insufficient, the scientists who wrote the new paper said.

The findings shed light on an ongoing debate among researchers. While there is consensus that greenhouse gas emissions have caused the planet to heat up since pre-industrial times, that warming had been steady for decades. But record-breaking temperatures in recent years have led scientists to question whether the pace of temperature gains is accelerating.

Demonstrating that was difficult due to natural fluctuations in temperatures. The researchers filtered out the “noise” to make the “underlying long-term warming signal” more clearly visible, said Grant Foster, a co-author of the study and a U.S.-based statistics expert.

Researchers isolated phenomena including the El Niño weather phase, volcanic eruptions and solar irradiance. When looking at temperature increases without their influence, the authors concluded the evidence is “strong” that the accelerated warming was not due to an unusually hot 2023 and 2024, but that since 2015 global temperatures departed from their previous, slower path of warming.

The new report adds to a growing body of work that indicates climate change is having a quicker and larger impact on the planet than scientists have understood. A separate paper published this week found that many studies on sea-level increases underestimate how much water along the coast has already risen.

“If the warming rate of the past 10 years continues, it would lead to a long-term exceedance of the 1.5C limit of the Paris Agreement before 2030,” said Stefan Rahmstorf, the lead author of the warming study and a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “How quickly the Earth continues to warm ultimately depends on how rapidly we reduce global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels to zero.”

Millan writes for Bloomberg.

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Pennsylvania5 days ago

Pennsylvania5 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death

-

Virginia6 days ago

Virginia6 days agoGiants will hold 2026 training camp in West Virginia

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoMamdani’s response to Trump’s Iran strike sparks conservative backlash: ‘Rooting for the ayatollah’