Science

NASA JPL team hopes to give greenhouse gas-monitoring satellite 'unprecedented' vision

It was almost 10 years ago when Andrew Thorpe received a text from the crew flying overhead in a small aircraft: They had spotted a new methane hot spot.

Thorpe drove along winding dirt and mountain roads in an unwieldy rental SUV near the Four Corners region of the southwestern U.S. When he arrived at the spot relayed from the plane, he pulled out a thermal camera to scan for the plume. Sure enough, methane was seeping out of the ground, likely from a pipeline leak.

He found a marker sticking out of the desert with the phone number for a gas company, so he gave them a call. “I had the most confused individual on the other side of the phone,” Thorpe said. “I was trying to explain to them why I was calling, but this was back many years ago when there really weren’t any technologies that could do this.”

Over the years, the work has gotten Thorpe some unwanted attention. “I did some driving surveys in California .… A rent-a-cop was very suspicious of me and tried to scare me off,” said Thorpe. “If you set up a thermal camera on a public road and you’re pointing it at a tank beyond the fence, people are going to get nervous. I’ve been heckled by some oil and gas workers, but that’s par for the course.”

Today, Thorpe is part of a group that is at the forefront of greenhouse gas monitoring at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. For over 40 years, the Microdevices Laboratory at JPL has developed specialized instruments to measure methane and carbon dioxide with extreme precision.

The instruments, called spectrometers, detect gases based on which colors of sunlight they absorb. Earlier this year, a team of researchers from JPL, Caltech and research nonprofit Carnegie Science was selected as a finalist for a NASA award to put the technology into orbit.

JPL technicians work on an Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer, or AVIRIS, that will be installed in an airplane to search for methane and other greenhouse gases.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

If chosen for the satellite mission, the team’s carbon investigation, called Carbon-I, would launch in the early 2030s. Over the course of three years, Carbon-I would continuously map greenhouse gas emissions around the globe and take daily snapshots of areas of interest, allowing scientists to identify sources of climate pollution, such as power plants, pipeline leaks, farms and landfills.

While there are already multiple satellites monitoring these gases, Carbon-I’s resolution is unprecedented and would eliminate any guesswork in determining where the gas was emitted. “There’s no denying it anymore — once we see a plume, there’s no other potential source,” said Christian Frankenberg, co-principal investigator for Carbon-I and a professor of environmental science and engineering at Caltech.

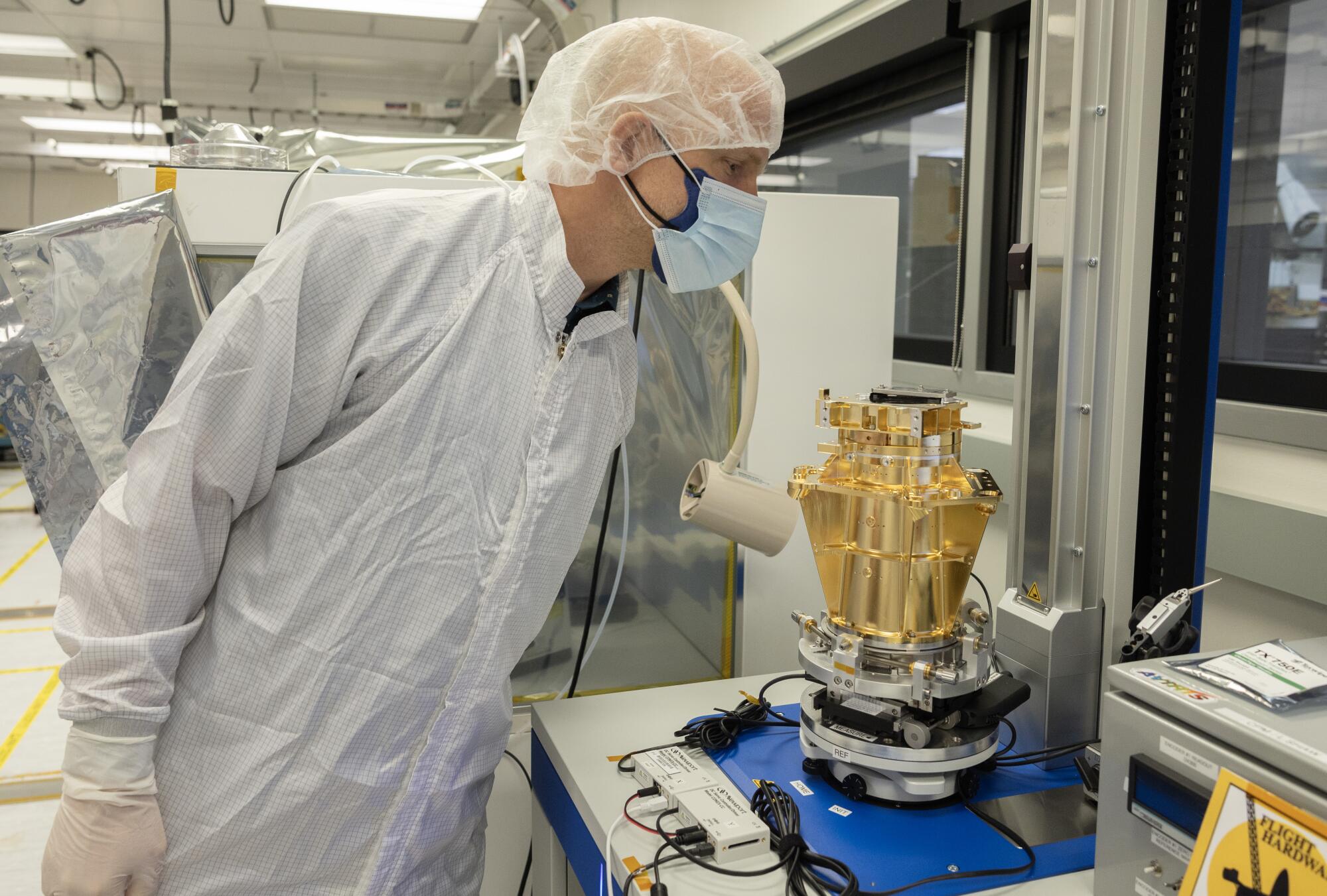

Caltech professor Christian Frankenberg, co-principal investigator for the proposed space-based Carbon-I emission-monitoring system, peers into an AVIRIS monitor under construction in a JPL lab.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

Carbon-I’s finest, 100-foot resolution “is a very high resolution from space. That’s an incredible resolution to be able to get,” said Debra Wunch, a professor at the University of Toronto who studies Earth’s carbon cycle and is not involved in the Carbon-I proposal. “It would be able to give us much more insight into exactly the source of emissions .… This would be groundbreaking. You would be able to see individual stacks, individual parts of landfills, even.”

Historically, monitoring the release of greenhouse gases from individual emitters has been challenging — both carbon dioxide and methane are colorless and odorless. So scientists have often had to rely on adding up self-reported values from companies and estimates from research. For example, to estimate the amount of methane cows produce, scientists would have to determine how much methane one cow releases and multiply it by the total number of cows on Earth.

“If you look at international policies … currently they’re all based on these bottom-up inventories,” said Anna Michalak, co-principal investigator for Carbon-I and the founding director of the Carnegie Climate and Resilience Hub at Carnegie Science. “We need to get to a point where … we actually have an independent way of tracking what the emissions are.”

Carbon-I’s resolution will also give scientists new access to the atmosphere of the tropics, where clouds currently obscure most forms of satellite surveillance. “It’s their Achilles’ heel,” said Frankenberg.

Since tropical and subtropical forests absorb roughly a quarter of the CO2 humanity produces by burning fossil fuels, accurate data from this region of the globe is badly needed.

Satellites currently orbiting Earth with lower resolution can’t see through small gaps in the cloud coverage. They only see a blurred average of the cloudy and clear spots in the sky for each pixel. Carbon-I, with each pixel’s area almost 50 times smaller than that of most other satellites, can see the clearings and take measurements through them. In an April 2024 paper, Frankenberg, Michalak and their collaborators estimated that Carbon-I would be able to see past the clouds in the tropics anywhere from 10 to 100 times more frequently than its predecessors.

Carbon-I “is going to see things where people don’t know what’s going on,” said Thorpe, who has moved on from his graduate school days pointing thermal cameras at gas leaks and now works as a research technologist with the Microdevices Laboratory. “It’s going to open a whole new realm of science.”

JPL’s airborne greenhouse gas-monitoring program goes back decades, but the field of space monitoring is still fairly new. Near the start of 2016, NASA headquarters contacted the JPL team. There was an ongoing massive blowout at the Aliso Canyon gas storage facility near Porter Ranch, and NASA wanted the team to check it out.

The team flew over the site in a variant of a 1960s-era spy plane on three days over the course of a month while the Southern California Gas Co. fought to contain the blowout. At the same time, NASA’s Goddard Flight Center in Maryland pointed the NASA Earth Observing spacecraft’s Hyperion spectrometer at the leak.

Hyperion was designed to make observations of the Earth’s surface and filter out noise from the atmosphere. Now, they were trying to observe the atmosphere and filter out the surface, and for the first time, scientists observed a human-made point source of methane from orbit.

“The Hyperion result was pretty noisy, but you could still see the plume,” said Thorpe. “This was really a proof of concept that we could do it from space.”

Even if Carbon-I launches, it doesn’t mean the team will stop putting instruments on planes. From aircraft, the team is able to monitor areas of interest in even sharper resolution and for consecutive days at a time. Right now, a leaner, meaner version of the spectrometers that observed the Four Corners leak and Aliso Canyon blowout is flying a series of missions to monitor the emissions of offshore oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico.

The twin-engine King Air plane used by JPL to conduct greenhouse gas-monitoring flights in its hangar at Hollywood Burbank Airport.

(Noah Haggerty/Los Angeles Times)

Plane missions also give the team an opportunity to try out new and improve spectrometers. “You can fix them, and you can upgrade them,” said JPL engineer Michael Eastwood, who’s worked with the spectrometers for over three decades and regularly flies with them. “You can take more risks, as opposed to spacecraft that need really mature, really well-known, high reliability — we’re not constrained like that.”

The air team is nimble, too. Typically, two crew members sit in the second row of a King Air twin-propeller aircraft looking at a stack of laptops and instruments with enough buttons to rival the plane’s cockpit. On the screens, they can look at real-time GPS data and spectrometer results and coordinate a flight plan with the pilots. The spectrometer — called AVIRIS, short for Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer — sits in the third row, looking down through a window cut out in the floor.

The NASA program for which Carbon-I was selected as a finalist aims to fund space-based Earth science that will benefit society. The team was awarded $5 million to sharpen its project proposal before a final NASA review in 2025. There are three other finalists, and two will be selected for the launch.

This two-step process for selecting missions is new for NASA’s Earth science programs and requires JPL to compete with the rest of the scientific community, independent of their association with the space agency.

“If we’re talking about grocery money, [$5 million] seems like a lot of money, but it’s really a bargain,” said Michalak. “If you think about the fact that you’re committing $300 million toward a mission, spending 1.5% of that to really make sure it’s going to be fabulous and successful is extremely smart.”

In the meantime, the Carbon-I team is focused on showing NASA that it has the technical know-how to execute the project on time and under budget.

“I think all four of the missions in the current phase are absolutely worthwhile scientific missions,” said Michalak, “and 50% odds are not bad odds for a satellite mission.”

Science

A virus without a vaccine or treatment is hitting California. What you need to know

A respiratory virus that doesn’t have a vaccine or a specific treatment regimen is spreading in some parts of California — but there’s no need to sound the alarm just yet, public health officials say.

A majority of Northern California communities have seen high concentrations of human metapneumovirus, or HMPV, detected in their wastewater, according to data from the WastewaterScan Dashboard, a public database that monitors sewage to track the presence of infectious diseases.

A Los Angeles Times data analysis found the communities of Merced in the San Joaquin Valley, and Novato and Sunnyvale in the San Francisco Bay Area have seen increases in HMPV levels in their wastewater between mid-December and the end of February.

HMPV has also been detected in L.A. County, though at levels considered low to moderate at this point, data show.

While HMPV may not necessarily ring a bell, it isn’t a new virus. Its typical pattern of seasonal spread was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic, and its resurgence could signal a return to a more typical pre-coronavirus respiratory disease landscape.

Here’s what you need to know.

What is HMPV?

HMPV was first detected in 2001, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s transmitted by close contact with someone who is infected or by touching a contaminated surface, said Dr. Neha Nanda, chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist for Keck Medicine of USC.

Like other respiratory illnesses, such as influenza, HMPV spreads and is more durable in colder temperatures, infectious-disease experts say.

Human metapneumovirus cases commonly start showing up in January before peaking in March or April and then tailing off in June, said Dr. Jessica August, chief of infectious diseases at Kaiser Permanente Santa Rosa.

However, as was the case with many respiratory viruses, COVID disrupted that seasonal trend.

Why are we talking about HMPV now?

Before the pandemic hit in 2020, Americans were regularly exposed to seasonal viruses like HMPV and developed a degree of natural immunity, August said.

That protection waned during the pandemic, as people stayed home or kept their distance from others. So when people resumed normal activities, they were more vulnerable to the virus. Unlike other viruses, there isn’t a vaccine for human metapneumovirus.

“That’s why after the pandemic we saw record-breaking childhood viral illnesses because we lacked the usual immunity that we had, just from lack of exposure,” August said. “All of that also led to longer viral seasons, more severe illness. But all of these things have settled down in many respects.”

In 2024, the national test positivity for HMPV peaked at 11.7% at the end of March, according to the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System. The following year’s peak was 7.15% in late April.

So far this year, the highest test positivity rate documented was 6.1%, reported on Feb. 21 — the most recent date for which complete data are available.

While the seasonal spread of viruses like HMPV is nothing new, people became more aware of infectious diseases and how to prevent them during the pandemic, and they’ve remained part of the public consciousness in the years since, August and Nanda said.

What are the symptoms of HMPV?

Most people won’t go to the doctor if they have HMPV because it typically causes mild, cold-like symptoms that include cough, fever, nasal congestion and sore throat.

HMPV infection can progress to:

- An asthma attack and reactive airway disease (wheezing and difficulty breathing)

- Middle ear infections behind the ear drum

- Croup, also known as “barking” cough — an infection of the vocal cords, windpipe and sometimes the larger airways in the lungs

- Bronchitis

- Fever

Anyone can contract human metapneumovirus, but those who are immunocompromised or have other underlying medical conditions are at particular risk of developing severe disease — including pneumonia. Young children and older adults are also considered higher-risk groups, Nanda said.

What is the treatment for HMPV?

There is no specified treatment protocol or antiviral medication for HMPV. However, it’s common for an infection to clear up on its own and treatment is mostly geared toward soothing symptoms, according to the American Lung Assn.

A doctor will likely send you home and tell you to rest and drink plenty of fluids, Nanda said.

If symptoms worsen, experts say you should contact your healthcare provider.

How to avoid contracting HMPV

Infectious-disease experts said the best way to avoid contracting HMPV is similar to preventing other respiratory illnesses.

The American Lung Assn.’s recommendations include:

- Wash your hands often with soap and water. If that’s not available, clean your hands with an alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

- Clean frequently touched surfaces.

- Crack open a window to improve air flow in crowded spaces.

- Avoid being around sick people if you can.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

Assistant data and graphics editor Vanessa Martínez contributed to this report.

Science

After rash of overdose deaths, L.A. banned sales of kratom. Some say they lost lifeline for pain and opioid withdrawal

Nearly four months ago, Los Angeles County banned the sale of kratom, as well as 7-OH, the synthetic version of the alkaloid that is its active ingredient. The idea was to put an end to what at the time seemed like a rash of overdose deaths related to the drug.

It’s too soon to tell whether kratom-related deaths have dissipated as a result — or, really, whether there was ever actually an epidemic to begin with. But many L.A. residents had become reliant on kratom as something of a panacea for debilitating pain and opioid withdrawal symptoms, and the new rules have made it harder for them to find what they say has been a lifesaving drug.

Robert Wallace started using kratom a few years ago for his knees. For decades he had been in pain, which he says stems from his days as a physical education teacher for the Glendale Unified School District between 1989 and 1998, when he and his students primarily exercised on asphalt.

In 2004, he had arthroscopic surgery on his right knee, followed by varicose vein surgery on both legs. Over the next couple of decades, he saw pain-management specialists regularly. But the primary outcome was a growing dependence on opioid-based painkillers. “I found myself seeking doctors who would prescribe it,” he said.

He leaned on opioids when he could get them and alcohol when he couldn’t, resulting in a strain on his marriage.

When Wallace was scheduled for his first knee replacement in 2021 (he had his other knee replaced a few years later), his brother recommended he take kratom for the post-surgery pain.

It seemed to work: Wallace said he takes a quarter of a teaspoon of powdered kratom twice a day, and it lets him take charge of managing his pain without prescription painkillers and eases harsh opiate-withdrawal symptoms.

He’s one of many Angelenos frustrated by recent efforts by the county health department to limit access to the drug. “Kratom has impacted my life in only positive ways,” Wallace told The Times.

For now, Wallace is still able to get his kratom powder, called Red Bali, by ordering from a company in Florida.

However, advocates say that the county crackdown on kratom could significantly affect the ability of many Angelenos to access what they say is an affordable, safer alternative to prescription painkillers.

Kratom comes from the leaves of a tree native to Southeast Asia called Mitragyna speciosa. It has been used for hundreds of years to treat chronic pain, coughing and diarrhea as well as to boost energy — in low doses, kratom appears to act as a stimulant, though in higher doses, it can have effects more like opioids.

Though advocates note that kratom has been used in the U.S. for more than 50 years for all sorts of health applications, there is limited research that suggests kratom could have therapeutic value, and there is no scientific consensus.

Then there’s 7-OH, or 7-Hydroxymitragynine, a synthetic alkaloid derived from kratom that has similar effects and has been on the U.S. market for only about three years. However, because of its ability to bind to opioid receptors in the body, it has a higher potential for abuse than kratom.

Public health officials and advocates are divided on kratom. Some say it should be heavily regulated — and 7-OH banned altogether — while others say both should be accessible, as long as there are age limitations and proper labeling, such as with alcohol or cannabis.

In the U.S., kratom and 7-OH can be found in all sorts of forms, including powder, capsules and liquids — though it depends on exactly where you are in the country. Though the Food and Drug Administration has recommended that 7-OH be included as a Schedule 1 controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act, that hasn’t been made official. And the plant itself remains unscheduled on the federal level.

That has left states, counties and cities to decide how to regulate the substances.

California failed to approve an Assembly bill in 2024 that would have required kratom products to be registered with the state, have labeling and warnings, and be prohibited from being sold to anyone younger than 21.

It would also have banned products containing synthetic versions of kratom alkaloids. The state Legislature is now considering another bill that basically does the same without banning 7-OH — while also limiting the amount of synthetic alkaloids in kratom and 7-OH products sold in the state.

“Until kratom and its pharmacologically active key ingredients mitragynine and 7-OH are approved for use, they will remain classified as adulterants in drugs, dietary supplements and foods,” a California Department of Public Health spokesperson previously told The Times.

On Tuesday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the state’s efforts to crack down on kratom products has resulted in the removal of more than 3,300 kratom and 7-OH products from retail stores. According to a news release from the governor’s office, there has been a 95% compliance rate from businesses in removing the products.

(Los Angeles Times photo illustration; source photos by Getty Images)

Newsom has equated these actions to the state’s efforts in 2024 to quash the sale of hemp products containing cannabinoids such as THC. Under emergency state regulations two years ago, California banned these specific hemp products and agents with the state Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control seized thousands of products statewide.

Since the beginning of 2026, there have been no reported violations of the ban on sales of such products.

“We’ve shown with illegal hemp products that when the state sets clear expectations and partners with businesses, compliance follows,” Newsom said in a statement. “This effort builds on that model — education first, enforcement where necessary — to protect Californians.”

Despite the state’s actions, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors is still considering whether to regulate kratom, or ban it altogether.

The county Public Health Department’s decision to ban the sale of kratom didn’t come out of nowhere. As Maral Farsi, deputy director of the California Department of Public Health, noted during a Feb. 18 state Senate hearing, the agency “identified 362 kratom-related overdose deaths in California between 2019 and 2023, with a steady increase from 38 in 2019 up to 92 in 2023.”

However, some experts say those numbers aren’t as clear-cut as they seem.

For example, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that in a number of recent L.A. County deaths that were initially thought to be caused by kratom or 7-OH, there wasn’t enough evidence to say those drugs alone caused the deaths; it might be the case that the danger is in mixing them with other substances.

Meanwhile, the actual application of this new policy seems to be piecemeal at best.

The county Public Health Department told The Times it conducted 2,696 kratom-related inspections between Nov. 10 and Jan. 27, and found 352 locations selling kratom products. The health department said the majority stopped selling kratom after those inspections; there were nine locations that ignored the warnings, and in those cases, inspectors impounded their kratom products.

But the reality is that people who need kratom will buy it on the black market, drive far enough so they get to where it’s sold legally or, like Wallace, order it online from a different state.

For now, retailers who sell kratom products are simply carrying on until they’re investigated by county health inspectors.

Ari Agalopol, a decorated pianist and piano teacher, saw her performances and classes abruptly come to a halt in 2012 after a car accident resulted in severe spinal and knee injuries.

“I tried my best to do traditional acupuncture, physical therapy and hydrocortisone shots in my spine and everything,” she said. “Finally, after nothing was working, I relegated myself to being a pain-management patient.”

She was prescribed oxycodone, and while on the medication, battled depression, anhedonia and suicidal ideation. She felt as though she were in a fog when taking oxycodone, and when it ran out, ”the pain would rear its ugly head.” Agalopol struggled to get out of bed daily and could manage teaching only five students a week.

Then, looking for alternatives to opioids, she found a Reddit thread in which people were talking up the benefits of kratom.

“I was kind of hesitant at first because there’re so many horror stories about 7-OH, but then I researched and I realized that the natural plant is not the same as 7-OH,” she said.

She went to a local shop, Authentic Kratom in Woodland Hills, and spoke to a sales associate who helped her decide which of the 47 strains of kratom it sold would best suit her needs.

Agalopol currently takes a 75-milligram dose of mitragynine, the primary alkaloid in kratom, when necessary. It has enabled her to get back to where she was before her injury: teaching 40 students a week and performing every weekend.

Agalopol believes the county hasn’t done its homework on kratom. “They’re just taking these actions because of public pressure, and public pressure is happening because of ignorance,” she said.

During the course of reporting this story, Authentic Kratom has shut down its three locations; it’s unclear if the closures are temporary. The owner of the business declined to comment on the matter.

When she heard the news of the recent closures, Agalopol was seething. She told The Times she has enough capsules of kratom for now, but when she runs out, her option will have to be Tylenol and ibuprofen, “which will slowly kill my liver.”

“Prohibition is not a public health strategy,” said Jackie Subeck, executive director of 7-Hope Alliance, a nonprofit that promotes safe and responsible access to 7-OH for consumers, at the Feb. 18 Senate hearing. “[It’s] only going to make things worse, likely resulting in an entirely new health crisis for Californians.”

Science

There were 13 full-service public health clinics in L.A. County. Now there are 6

Because of budget cuts, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health has ended clinical services at seven of its public health clinic sites.

As of Feb. 27, the county is no longer providing services such as vaccinations, sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment, or tuberculosis diagnosis and specialty TB care at the affected locations, according to county officials and a department fact sheet.

The sites losing clinical services are Antelope Valley in Lancaster; the Center for Community Health (Leavy) in San Pedro, Curtis R. Tucker in Inglewood, Hollywood-Wilshire, Pomona, Dr. Ruth Temple in South Los Angeles, and Torrance. Services will continue to be provided by the six remaining public health clinics, and through nearby community clinics.

The changes are the result of about $50 million in funding losses, according to official county statements.

“That pushed us to make the very difficult decision to end clinical services at seven of our sites,” said Dr. Anish Mahajan, chief deputy director of the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

Mahajan said the department selected clinics with relatively lower patient volumes. Over the last month, he said, the department has sent letters to patients about the changes, and referred them to unaffected county clinics, nearby federally qualified health centers or other community providers. According to Mahajan, for tuberculosis patients, particularly those requiring directly observed therapy, public health nurses will continue visiting patients.

Public health clinics form part of the county’s healthcare safety net, serving low-income residents and those with limited access to care. Officials said that about half of the patients the county currently sees across its clinics are uninsured.

Mahajan noted that the clinics were established decades ago, before the Affordable Care Act expanded Medi-Cal coverage and increased the number of federally qualified health centers. He said that as more residents gained access to primary care, utilization at some county-run clinics declined.

“Now that we have a more sophisticated safety net, people often have another place to go for their full range of care,” he said.

Still, the closures have unsettled providers who work closely with local vulnerable populations.

“I hate to see any services that serve our at-risk and homeless community shut down,” said Mark Hood, chief executive of Union Rescue Mission in downtown Los Angeles. “There’s so much need out there, so it always is going to create hardship for the people that actually need the help the most.”

Union Rescue Mission does not receive government funding for its healthcare services, Hood said. The mission’s clinics are open not only to shelter guests, up to 1,000 people nightly, but also to people living on the streets who walk in seeking care.

Its dental clinic alone sees nearly 9,000 patients a year, Hood said.

“We haven’t seen it yet, but I expect in the coming days and weeks we’ll see more people coming through our doors looking for help,” he said. “They’re going to have to find help somewhere.” Hood said women experiencing homelessness are especially vulnerable when preventive care, including sexual and reproductive health services, becomes harder to access.

County officials said staffing impacts so far have been managed through reassignment rather than layoffs. Roughly 200 to 300 positions across the department have been eliminated amid funding cuts, officials said, though many were vacant. About 120 employees whose positions were affected have been reassigned; according to Mahajan, no one has been laid off.

The clinic closures come amid broader fiscal uncertainty. Mahajan said that due to the Trump administration’s “Big Beautiful Bill,” Los Angeles County could lose $2.4 billion over the next several years. That funding, he said, supports clinics, hospitals and community clinic partners now absorbing patients who previously went to the clinics that closed on Feb. 27.

In response, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors has backed a proposed half-cent sales tax measure that would generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually for healthcare and public health services. Voters are expected to consider the measure in June.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Wisconsin3 days ago

Wisconsin3 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Florida4 days ago

Florida4 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Oregon5 days ago

Oregon5 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling