Science

I went to an overdose prevention site. Biden and Newsom need to stop blocking them

Isaias Lopez was dying, but he didn’t know it.

Lopez was slumped against a wall in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, where the concentration of homelessness and drug use have divided this city politically.

A baby blue baseball cap and a white hoodie covered his head, making him just another human lump to be avoided by passersby. He had begun to nod off from the fentanyl that minutes ago was in a scrap of tin foil that now lay nearly empty on his legs.

Lopez’s oxygen saturation level had fallen to 87%, according to a thumb monitor that aid workers from a nearby illegally run safe consumption site had slipped on him; he was in danger of passing out and never waking up. They roused him as best they could, then put an oxygen mask on him, likely saving his life.

A man smokes drugs at an illegal-drug safe-injection site in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

Minutes earlier, I stood less than a block away as a Latino man I’ll call E. almost died from another fentanyl overdose. E. was behind a concrete barrier on the sidewalk, his breathing stopped but his heart still beating. The same aid workers, from the same illegal overdose prevention operation, rubbed his chest. The oxygen mask went on. Two doses of Narcan later, he was up and walking away.

“Just another day around here,” said E.’s friend Jabari M., who had run for the Narcan when he realized what was happening. He asked that I not use his full name because of the stigma of being on the streets.

Two lives saved before lunch — by rogue activists breaking the law to do it.

“Saving lives is an act of civil disobedience,” Lydia Bransten, one of those illicit do-gooders, told me. “Insane.”

In a city where more than 470 people have already died of overdoses this year, putting it on track to be the most deadly year for drug deaths on record, I have to disagree.

Keeping overdose prevention sites illegal isn’t insane, implying a lack of control over the situation. It’s cruel, to those addicted and those that care about them — a move that puts optics and politics over lives.

But that’s the political decision that has been made by President Biden, seconded by Gov. Gavin Newsom and now left for mayors, such as San Francisco’s London Breed, to sort out. I’ll explain that in a minute.

Activists ran an illegal-drug safe-injection site in San Francisco as a protest on International Overdose Awareness Day.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

The overdoses I witnessed happened on Willow Street in the Tenderloin. Fed-up activists, many with city-related or nonprofit day jobs, had taken time off to create an illegal safe drug consumption site under two gray pop-up tents here, with “the war against us,” scrawled in colored chalk on the road.

A half-dozen people smoked mostly fentanyl inside one, while intravenous drug users injected in the other — all under the watchful eyes of staff who know how to reverse an overdose.

It was a protest on International Overdose Awareness Day against the city’s inaction on creating permanent places where people can be monitored while they do drugs — sometimes called overdose prevention centers or safe consumption sites.

Such places sound extreme but are successfully running in New York City and have been used for decades in Vancouver and Europe. These centers protect the lives of people like Lopez and E., who would otherwise do drugs in dangerous situations.

But they are also meant to take drug use out of the public view, making streets safer and cleaner.

This stretch of Willow Street has for years been home to tents and addiction, despite dozens of attempts by the city to sweep it clean. It represents the kind of frustration that has polarized this city and created an unexpected conservative backlash to harm reduction policies for drug users in recent months, especially those visibly living on the streets.

A pop-up site for safe injections in San Francisco.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

A few blocks from here, the city had until December allowed some of these same activists to run an overdose prevention site in a homeless services center, not necessarily condoning it but not stopping it. It was a don’t ask/don’t tell situation that sent the Fox News types into a spin.

The ensuing pressure caused the city to shut it down, promising to come up with a plan to open safe consumption sites in multiple neighborhoods.

But then, like so many places recently, the pendulum swung. San Francisco, once the undisputed champion of progressive politics in the Golden State and maybe the country, is over it.

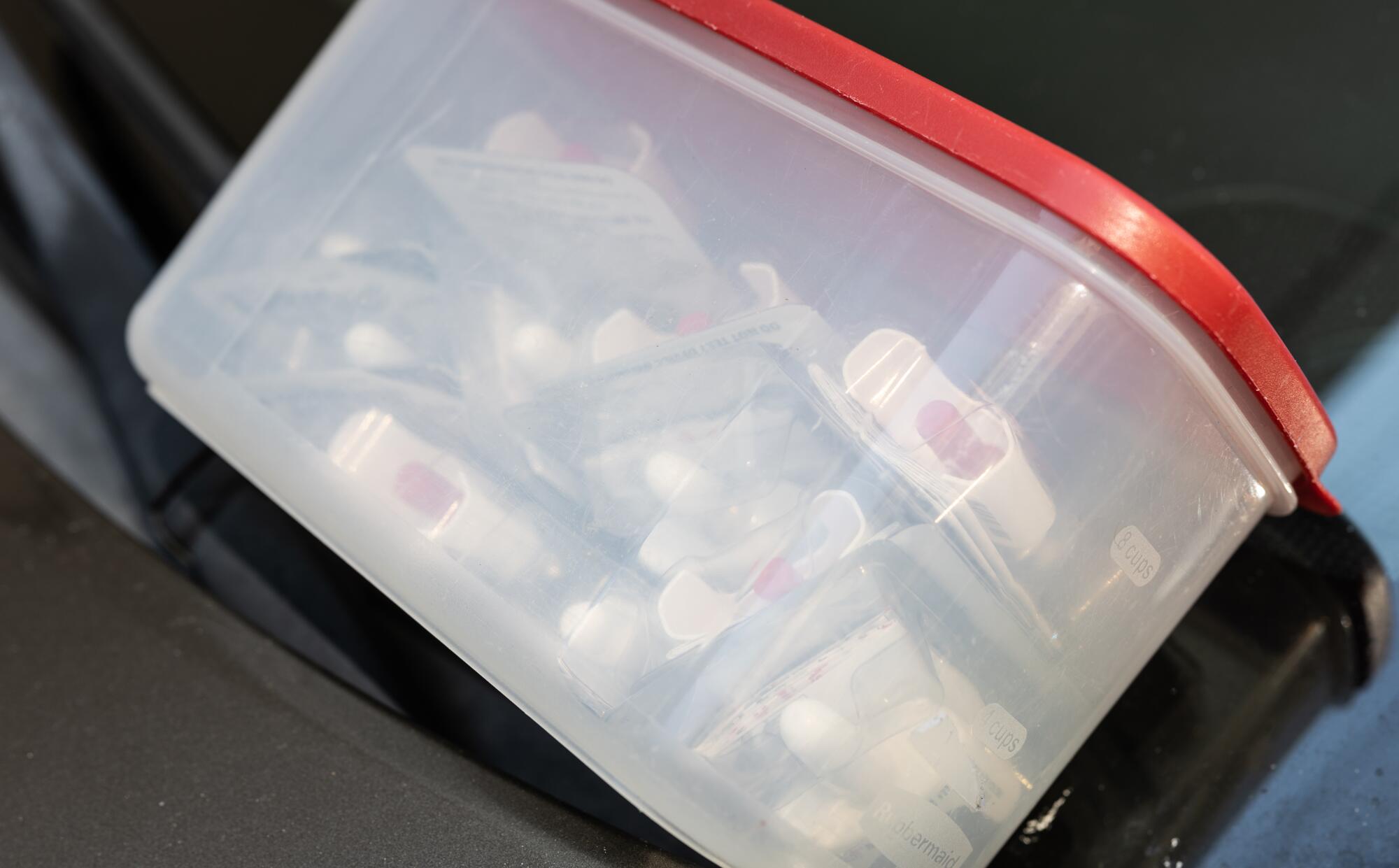

A container of Narcan sits on a windshield of a car at an illegal injection pop-up site in San Francisco.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

“This city is being taken advantage of, and we are tired of it,” Breed told a raucous crowd in front of a federal courthouse here last week, as she fought to lift a ban on sweeping homeless encampments.

In recent months, Breed and some city leaders have curved toward traditionally conservative policies on how drug addiction and homelessness should be addressed, championing efforts on multiple fronts to end open drug sales and consumption and clear streets largely through law enforcement tactics.

Under new policies, police are not only cracking down on open drug markets where dealers sell with impunity, but are threatening to arrest those using drugs. It’s a controversial move that hearkens to the failed tough-love days of the first “War on Drugs” that filled jails with Black and brown people who were — and still are — overrepresented in the ranks of incarceration, those facing addiction and homelessness.

One city supervisor, Matt Dorsey — a former spokesman for the Police Department and a former drug user — has even suggested cutting off money reserved to create “wellness hubs” around the city and instead dumping the millions into “jail-based recovery.”

When I spoke with Dorsey, he told me he supported safe consumption sites but didn’t see them as politically viable right now, especially in his district, which includes places where the drug problem is indisputably impeding the quality of life for housed and unhoused people alike.

“I had never seen the city as close to pitchforks and torches as I do now,” he told me.

David Helgren smokes a drug at an illegal drug pop-up site on Willow and Polk streets in San Francisco.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

There’s a “fix it or we’ll find someone who can” mentality, he said, making it impossible for him to open a wellness hub in his district because people fear it would make the neighborhood worse. If there were multiple hubs open at once — all with safe consumption sites that could help alleviate the visible problem — then he would support them, he said.

But here is where it gets complicated and Biden and Newsom come into the mix.

Safe consumption sites are illegal under a federal law known as the “crack house statute,” which basically makes it a serious crime to open or maintain any building for the purpose of using a controlled substance. That law was put in place as part of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, meant to address — you guessed it — crack houses.

A nonprofit in Philadelphia has litigated with the federal government in multiple cases in a bid to change or at least curb that law. For a while, it looked like Biden’s Department of Justice was going to work out a compromise, taking away the risk of criminal prosecution for those who run overdose prevention centers.

But the talks collapsed and the case continues to wind through the courts, leaving a real risk of criminal and civil liability for states, cities and nonprofits — and even the staff who would work in such centers — who feel compelled to do anything and everything to save lives during this national epidemic of drug deaths.

“I would expect this in a Trump administration. I wouldn’t expect this in a Biden administration,” Dorsey said. He doesn’t see Biden addressing the issue unless he wins a second term.

Newsom had a chance last year to allow California to take on the brunt of the liability, but he punted.

Terry Morris hands out drug paraphernalia to visitors at an illegal injection pop-up site in San Francisco.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

Legislators passed a bill that would have allowed pilot programs in San Francisco, Los Angeles and a couple of other places to open overdose prevention centers. Newsom vetoed the bill, citing a fear of unintended consequences. He kicked the issue to the Department of Health and Human Services for further study.

As far as I was able to determine, it has held one virtual meeting, done some site visits and quiet-buried the whole thing.

To be fair, Newsom has invested heavily in other ways to combat the fentanyl crisis — more than $150 million for naloxone distribution, $61 million for other types of harm reduction, $30 million to develop a generic version of Narcan. All good stuff.

But his latest plan, released in March, makes no mention of overdose prevention sites.

That leaves the whole mess in local hands — Breed’s to be specific. Her office didn’t return my call, but she’s said in the past she supports safe consumption sites.

If.

If the liability issue can be worked out. Which it really can’t unless the federal or state government steps in.

So back to the activists, who aren’t willing to wait. And back to those with addictions, many of whom hate the idea that their disease — yes, addiction is a medically treatable condition — is making life untenable for those around them.

Jamal Wilson feels that way. He came to the pop-up on Thursday to smoke fentanyl in a place that was safe and out of the way. He’s from South Los Angeles and moved up here because the fetty, as he calls it, was cheaper. Folks up here call him L.A.

Wilson didn’t start using drugs until two painful back surgeries at the age of 36. Until then, he’d been just a regular a father with a college degree in political science and child development, the kind of guy who loved to roll around on the grass with his two kids and pretend to be “Star Wars” characters.

But a nearly unlimited prescription for OxyContin got him hooked. Soon, he was crushing the pills and snorting them. Then he turned to street drugs. Ten years later, here he is.

“Fentanyl makes you turn your back on the ones you love the most,” he told me, thinking of those kids. He believes he will some day get this addiction under control, though he says he feels so far away from his old life that he can’t see the path.

“I am still a person,” he told me. “When you shun us, you forget we are someone’s son or daughter.”

And that’s really all of it. If any of the people on this street were my kids, I would hope there was a Lydia Bransten around to save their life, to give them a place of safety, respite and respect in the hopes it allowed them to see a path back to their old life.

A man who overdosed was given two Narcan doses by Jabari M., left, and activists administered oxygen to revive him.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Times)

When I talked to Jabari after E. overdosed, he told me E. was “a person anyone would want as a friend,” smart and funny.

And though Jabari had saved a life, he didn’t see himself as any kind of hero.

“My mom and dad would kill me if I didn’t do something to be the change,” he told me as his dog Mia lapped up the remains of a carton of strawberry cream cheese.

Someone’s son.

Of course our drug crisis is complicated and hard to understand — and often ugly. When I found Lopez, the other man who overdosed, around the corner, he told me it was all a mistake — the aid workers had been confused and he didn’t need help.

“I’m good,” Lopez, an immigrant from Guatemala who has lived on the streets for six years, told me as he searched for a lighter to smoke the tiny nugget of fentanyl remaining on his crumpled tin foil.

I walked him back to the safe consumption site, worried smoking again so soon wasn’t the best idea. I didn’t want to leave this stretch of misery thinking he would just sit down against another wall and die, unnoticed.

That’s the most terrifying part of a fentanyl overdose, how truly uneventful it is and how easy to miss if no one is watching.

But also a death easy to avoid, if someone is.

Science

Cluster of farmworkers diagnosed with rare animal-borne disease in Ventura County

A cluster of workers at Ventura County berry farms have been diagnosed with a rare disease often transmitted through sick animals’ urine, according to a public health advisory distributed to local doctors by county health officials Tuesday.

The bacterial infection, leptospirosis, has resulted in severe symptoms for some workers, including meningitis, an inflammation of the brain lining and spinal cord. Symptoms for mild cases included headaches and fevers.

The disease, which can be fatal, rarely spreads from human to human, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Ventura County Public Health has not given an official case count but said it had not identified any cases outside of the agriculture sector. The county’s agriculture commissioner was aware of 18 cases, the Ventura County Star reported.

The health department said it was first contacted by a local physician in October, who reported an unusual trend in symptoms among hospital patients.

After launching an investigation, the department identified leptospirosis as a probable cause of the illness and found most patients worked on caneberry farms that utilize hoop houses — greenhouse structures to shelter the crops.

As the investigation to identify any additional cases and the exact sources of exposure continues, Ventura County Public Health has asked healthcare providers to consider a leptospirosis diagnosis for sick agricultural workers, particularly berry harvesters.

Rodents are a common source and transmitter of disease, though other mammals — including livestock, cats and dogs — can transmit it as well.

The disease is spread through bodily fluids, such as urine, and is often contracted through cuts and abrasions that contact contaminated water and soil, where the bacteria can survive for months.

Humans can also contract the illness through contaminated food; however, the county health agency has found no known health risks to the general public, including through the contact or consumption of caneberries such as raspberries and blackberries.

Symptom onset typically occurs between two and 30 days after exposure, and symptoms can last for months if untreated, according to the CDC.

The illness often begins with mild symptoms, with fevers, chills, vomiting and headaches. Some cases can then enter a second, more severe phase that can result in kidney or liver failure.

Ventura County Public Health recommends agriculture and berry harvesters regularly rinse any cuts with soap and water and cover them with bandages. They also recommend wearing waterproof clothing and protection while working outdoors, including gloves and long-sleeve shirts and pants.

While there is no evidence of spread to the larger community, according to the department, residents should wash hands frequently and work to control rodents around their property if possible.

Pet owners can consult a veterinarian about leptospirosis vaccinations and should keep pets away from ponds, lakes and other natural bodies of water.

Science

Political stress: Can you stay engaged without sacrificing your mental health?

It’s been two weeks since Donald Trump won the presidential election, but Stacey Lamirand’s brain hasn’t stopped churning.

“I still think about the election all the time,” said the 60-year-old Bay Area resident, who wanted a Kamala Harris victory so badly that she flew to Pennsylvania and knocked on voters’ doors in the final days of the campaign. “I honestly don’t know what to do about that.”

Neither do the psychologists and political scientists who have been tracking the country’s slide toward toxic levels of partisanship.

Fully 69% of U.S. adults found the presidential election a significant source of stress in their lives, the American Psychological Assn. said in its latest Stress in America report.

The distress was present across the political spectrum, with 80% of Republicans, 79% of Democrats and 73% of independents surveyed saying they were stressed about the country’s future.

That’s unhealthy for the body politic — and for voters themselves. Stress can cause muscle tension, headaches, sleep problems and loss of appetite. Chronic stress can inflict more serious damage to the immune system and make people more vulnerable to heart attacks, strokes, diabetes, infertility, clinical anxiety, depression and other ailments.

In most circumstances, the sound medical advice is to disengage from the source of stress, therapists said. But when stress is coming from politics, that prescription pits the health of the individual against the health of the nation.

“I’m worried about people totally withdrawing from politics because it’s unpleasant,” said Aaron Weinschenk, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay who studies political behavior and elections. “We don’t want them to do that. But we also don’t want them to feel sick.”

Modern life is full of stressors of all kinds: paying bills, pleasing difficult bosses, getting along with frenemies, caring for children or aging parents (or both).

The stress that stems from politics isn’t fundamentally different from other kinds of stress. What’s unique about it is the way it encompasses and enhances other sources of stress, said Brett Ford, a social psychologist at the University of Toronto who studies the link between emotions and political engagement.

For instance, she said, elections have the potential to make everyday stressors like money and health concerns more difficult to manage as candidates debate policies that could raise the price of gas or cut off access to certain kinds of medical care.

Layered on top of that is the fact that political disagreements have morphed into moral conflicts that are perceived as pitting good against evil.

“When someone comes into power who is not on the same page as you morally, that can hit very deeply,” Ford said.

Partisanship and polarization have raised the stakes as well. Voters who feel a strong connection to a political party become more invested in its success. That can make a loss at the ballot box feel like a personal defeat, she said.

There’s also the fact that we have limited control over the outcome of an election. A patient with heart disease can improve their prognosis by taking medicine, changing their diet, getting more exercise or quitting smoking. But a person with political stress is largely at the mercy of others.

“Politics is many forms of stress all rolled into one,” Ford said.

Weinschenk observed this firsthand the day after the election.

“I could feel it when I went into my classroom,” said the professor, whose research has found that people with political anxiety aren’t necessarily anxious in general. “I have a student who’s transgender and a couple of students who are gay. Their emotional state was so closed down.”

That’s almost to be expected in a place like Wisconsin, whose swing-state status caused residents to be bombarded with political messages. The more campaign ads a person is exposed to, the greater the risk of being diagnosed with anxiety, depression or another psychological ailment, according to a 2022 study in the journal PLOS One.

Political messages seem designed to keep voters “emotionally on edge,” said Vaile Wright, a licensed psychologist in Villa Park, Ill., and a member of the APA’s Stress in America team.

“It encourages emotion to drive our decision-making behavior, as opposed to logic,” Wright said. “When we’re really emotionally stimulated, it makes it so much more challenging to have civil conversation. For politicians, I think that’s powerful, because emotions can be very easily manipulated.”

Making voters feel anxious is a tried-and-true way to grab their attention, said Christopher Ojeda, a political scientist at UC Merced who studies mental health and politics.

“Feelings of anxiety can be mobilizing, definitely,” he said. “That’s why politicians make fear appeals — they want people to get engaged.”

On the other hand, “feelings of depression are demobilizing and take you out of the political system,” said Ojeda, author of “The Sad Citizen: How Politics is Depressing and Why it Matters.”

“What [these feelings] can tell you is, ‘Things aren’t going the way I want them to. Maybe I need to step back,’” he said.

Genessa Krasnow has been seeing a lot of that since the election.

The Seattle entrepreneur, who also campaigned for Harris, said it grates on her to see people laughing in restaurants “as if nothing had happened.” At a recent book club meeting, her fellow group members were willing to let her vent about politics for five minutes, but they weren’t interested in discussing ways they could counteract the incoming president.

“They’re in a state of disengagement,” said Krasnow, who is 56. She, meanwhile, is looking for new ways to reach young voters.

“I am exhausted. I am so sad,” she said. “But I don’t believe that disengaging is the answer.”

That’s the fundamental trade-off, Ojeda said, and there’s no one-size-fits-all solution.

“Everyone has to make a decision about how much engagement they can tolerate without undermining their psychological well-being,” he said.

Lamirand took steps to protect her mental health by cutting social media ties with people whose values aren’t aligned with hers. But she will remain politically active and expects to volunteer for phone-banking duty soon.

“Doing something is the only thing that allows me to feel better,” Lamirand said. “It allows me to feel some level of control.”

Ideally, Ford said, people would not have to choose between being politically active and preserving their mental health. She is investigating ways to help people feel hopeful, inspired and compassionate about political challenges, since these emotions can motivate action without triggering stress and anxiety.

“We want to counteract this pattern where the more involved you are, the worse you are,” Ford said.

The benefits would be felt across the political spectrum. In the APA survey, similar shares of Democrats, Republicans and independents agreed with statements like, “It causes me stress that politicians aren’t talking about the things that are most important to me,” and, “The political climate has caused strain between my family members and me.”

“Both sides are very invested in this country, and that is a good thing,” Wright said. “Antipathy and hopelessness really doesn’t serve us in the long run.”

Science

Video: SpaceX Unable to Recover Booster Stage During Sixth Test Flight

President-elect Donald Trump joined Elon Musk in Texas and watched the launch from a nearby location on Tuesday. While the Starship’s giant booster stage was unable to repeat a “chopsticks” landing, the vehicle’s upper stage successfully splashed down in the Indian Ocean.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoColumn: Molly White's message for journalists going freelance — be ready for the pitfalls

-

Science6 days ago

Science6 days agoTrump nominates Dr. Oz to head Medicare and Medicaid and help take on 'illness industrial complex'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump taps FCC member Brendan Carr to lead agency: 'Warrior for Free Speech'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoInside Elon Musk’s messy breakup with OpenAI

-

Lifestyle1 week ago

Lifestyle1 week agoSome in the U.S. farm industry are alarmed by Trump's embrace of RFK Jr. and tariffs

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoProtesters in Slovakia rally against Robert Fico’s populist government

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoHoliday gatherings can lead to stress eating: Try these 5 tips to control it

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThey disagree about a lot, but these singers figure out how to stay in harmony

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25286459/247024_Pilot_Pen_CVirginia.jpg)