Science

'I don't want him to go': An autistic teen and his family face stark choices

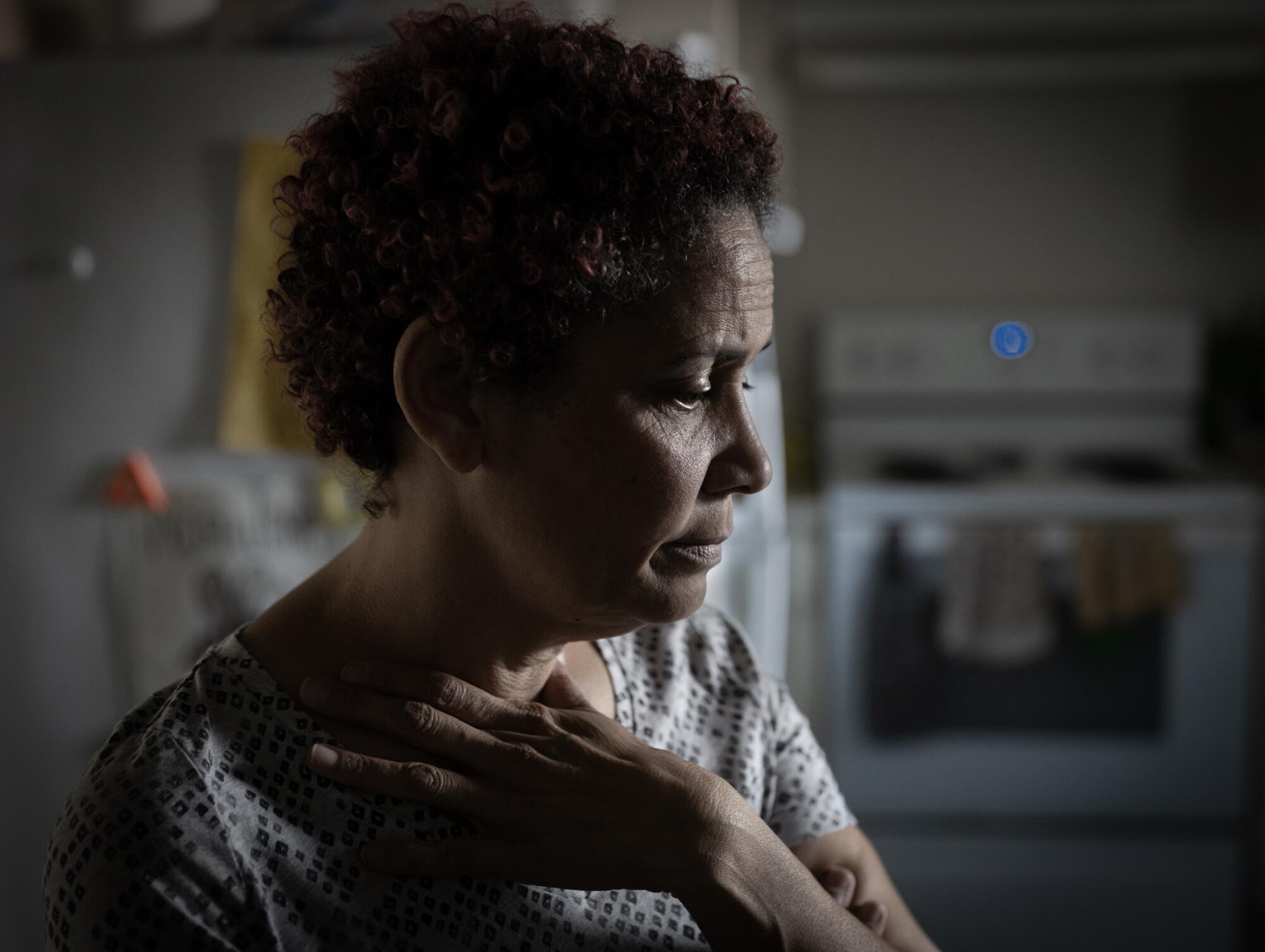

Christine LyBurtus was aching and fearful of what might happen when her 13-year-old son returned home.

Noah had been sent to Children’s Hospital of Orange County for a psychiatric hold lasting up to 72 hours after he punched at walls, flipped over a table, ripped out a chunk of his mother’s hair and tried to break a car window.

“There’s nothing else to call it except a psychotic episode,” LyBurtus said.

The clock was ticking on that August day in 2022. The single mother wanted help to prevent such an episode from happening again, maybe with a different medication. Hospital staff were waiting for a psychiatric bed, possibly at another hospital with a dedicated unit for patients with autism or other developmental disabilities.

But as the hours ran out on the hold, it became clear that wasn’t happening. LyBurtus brought Noah home to their Fullerton apartment.

“When he came back home, it kind of broke my heart,” said his sister, Karissa, who is two years older. “He looked like, ‘What the heck did you guys put me into?’”

Christine LyBurtus makes a snack for Noah.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The next night, Noah was back in the ER after smashing a television and attacking his mother. This time, he was transferred to a different hospital for three weeks, prescribed medications for psychosis, and then sent to a residential facility in Garden Grove.

LyBurtus said she was told it would be a stopgap measure — just for three weeks — until she could line up more help at home. But when she phoned to ask about visiting her son, LyBurtus said she was told she couldn’t see him for a month.

“He lives here now,” someone told her, she said, and the staff needed time to “break him in.”

LyBurtus felt like she was being pushed to give up her son, instead of getting the help her family needed. She insisted on bringing him home.

::

Autism is a developmental condition that can shape how people think, communicate, move and process sensory information. When Noah was 3, a doctor noted he was a “very cute little boy” who played alone, rocked back and forth, and sometimes bit himself. Noah’s eye contact was “fleeting.” He could speak about 20 words, but often cried or pulled his mother’s hand to communicate.

The physician summed up his behavior as “characteristic of a DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder.”

When he was in elementary school, LyBurtus stopped working full time outside the home and enrolled in a state program that paid her as his caregiver. She relies on Medi-Cal for his medical care, and much of his schooling has been in Orange County-run programs for children with moderate to severe disabilities.

Noah does not speak but sometimes uses pictures, an app on a tablet, or some sign language to communicate. When a reporter visited their home last year, Noah bobbed his head and shoulders as he listened to music on his iPad. He flapped his hands as LyBurtus made him a peanut-butter-and-banana smoothie, and then dutifully followed her instructions to chuck the peel and put the almond milk away. It was a good day, LyBurtus said with relief.

But on other days, LyBurtus said her son could be rigid; his demands, unpredictable. “Some days he’s fixated on having three pairs of pants on … Some days he wants to take seven showers. The next day, I can’t get him to take showers.”

Christine LyBurtus greets Noah as he arrives home from school.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

When frustrated, Noah might erupt, banging his head against walls and trying to jump out the windows of their apartment. He had kicked and bitten his mother when she tried to redirect him. In the worst instances, LyBurtus had resorted to hiding in the bathroom — her “safe room” — and urged Karissa to lock herself in the bedroom.

As Noah grew taller and stronger, LyBurtus stripped bare the walls of her apartment to try to make it safe, installed shatterproof windows and removed a knob from a closet door to prevent Noah from using it as a foothold to scale over the top of the closet door. She made sure to flag her address for the Fullerton Police Department so it knew her son was developmentally disabled.

“I’m just so grateful that my son never got shot,” LyBurtus said.

Each of the 911 calls was the start of a Sisyphean routine. Noah “has been challenging to place in [a] mental health facility due to behavioral care needs with severe autism,” a doctor wrote when he was back at Children’s Hospital of Orange County yet again.

Noah leaps into the air inside his Fullerton home. At left is Terrence Morris, one of Noah’s caregivers.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

As the family tried to get through each crisis, LyBurtus was also facing a common struggle among parents of California children with disabilities: not getting the help they were supposed to receive from the state.

LyBurtus was getting assistance through a local regional center, one of the nonprofit agencies contracted by the California Department of Developmental Services. She said she’d been authorized to receive 40 hours weekly of respite care — meant to relieve families of children with disabilities for short periods — but was sometimes receiving only 12 to 16 hours.

She was also supposed to have two workers at a time, LyBurtus said, but caregivers were so scarce that she was scheduling one at a time in order to cover as many hours as she could.

In the meantime, Noah wasn’t sleeping and she was going through so much laundry detergent and quarters that her grocery budget was drained. At one point, she wanted to go to a food bank, but there would be no one to watch him.

“I could not be anymore tired and frustrated!!!!” she wrote to her regional center coordinator. “Is the only way Noah is going to get help [is] if I abandoned him and surrender him to the State!?!?”

Christine LyBurtus said she’s struggled to find the right care for Noah.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

::

Across the country, surging numbers of young people have landed in emergency rooms in the throes of a mental health crisis amid a shortage of needed care. Children in need of psychiatric care are routinely held in emergency departments for hours or even days. Even amid COVID, as people tried to avoid emergency rooms, mental health-related visits continued to rise among teens in 2021 and 2022.

Among those hit hardest by the crisis are autistic youth, who turn up in emergency rooms at higher rates than other kids — and are much more likely to do so for psychiatric issues. Many have overlapping conditions such as anxiety, and researchers have also found they face a higher risk of abuse and trauma.

“We’re a misunderstood, marginalized population of people” at higher risk of suicide, Lisa Morgan, founder of the Autism and Suicide Prevention Workgroup, said at a national meeting.

Yet the available assistance is “not designed for us.”

According to the National Autism Indicators Report, more than half of parents of autistic youth who were surveyed had trouble getting the mental health services their autistic kids needed, with 22% saying it was “very difficult” or “impossible.” A report commissioned by L.A. County found autistic youth were especially likely to languish in ERs amid few options for ongoing psychiatric treatment.

Karissa interacts with her brother, Noah, as he watches a video after school.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In decades past, many psychiatrists were unwilling to diagnose mental health disorders in autistic people, believing “it was either part of the autism or for other reasons it was undiagnosable,” said Jessica Rast, an assistant research professor affiliated with the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute. Much more is now known about both autism and mental health treatment, but experts say the two fields aren’t consistently linked in practice.

Mental health providers may focus on an autism diagnosis for a prospective patient and say, “‘Well, that’s not in our wheelhouse. We’re treating things like depression or anxiety,’” said Brenna Maddox, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

Yet patients or their families “weren’t asking for autism treatment. They were asking for depression or anxiety or other mental health treatment,” Maddox said.

In the meantime, the system that serves children with developmental disabilities has faltered.

“Never have I seen that we can’t staff the needed things on so many cases,” Larry Landauer, executive director of the Regional Center of Orange County, said last year. Statewide, “there’s thousands and thousands of cases that are struggling.”

“If I’m a respite worker and I get called on to provide help to families … who am I going to select?” Landauer asked. “The [person] that watches TV and plays on his iPad and I just sit and monitor him? Or do I take someone that is significantly behaviorally challenged — that pulls my hair, that scares me all the time, that tries to run out the door? … Those are the ones getting left out.”

::

The fall and winter of 2022 were so trying that LyBurtus eventually took matters into her own hands. Noah bit his mother and smashed a bathroom window and tried to climb out before the Fullerton Fire Department arrived. Weeks later, LyBurtus had to dial 911 again after he bit his sister’s finger badly enough to draw blood.

Caregiver Terrence Morris, left, keeps a watchful eye on Noah.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

He ended up in a hold at Children’s Hospital of Orange County, which searched for another facility that might help him, but “all placement options declined patient placement,” according to his medical records.

Noah was again sent home with his mother, but the next day, he was back at Children’s Hospital of Orange County after slamming his head against a tile floor.

LyBurtus, frantic and bruised, made call after call and finally used her credit card to pay for an ambulance to take him to UCLA Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital, where he was admitted.

Week by week, psychiatrists there said Noah seemed to be making some strides as they adjusted his alphabet soup of medications. But hospital staff struggled to understand what would set him off.

Once, while playing cards, Noah suddenly started knocking the cards off the table and struck another patient in the face. Another day, he appeared suddenly to be frightened after using the bathroom, and then charged at a computer plugged in nearby.

But there were also days when he danced to a Michael Jackson song, or played Giant Jenga outside on the deck. One day, a doctor wrote, “He made eye contact for a few seconds. I waved to him, and he looked at his hand, as though he was wondering what to do with it in return.”

Christine LyBurtus washes her son’s face. When Noah was 3, a doctor noted he was a “very cute little boy” who played alone, rocked back and forth, and sometimes bit himself.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

LyBurtus was straining to find more help at home so UCLA held off on discharging him, but at the end of January 2023 Noah was sent home. With no changes in medication planned, “and the strong possibility that Noah grew tired of the inpatient setting, the ward no longer was deemed therapeutic or necessary,” a doctor wrote.

Less than a month later, he was back in the emergency room at Children’s Hospital of Orange County after biting and attacking his mother.

A psychiatrist at the pediatric hospital wrote that because he had limited ability to communicate, another round of psychiatric hospitalization would do little unless it was specialized for “individuals with neurodevelopmental needs.” When the 72-hour hold at children’s hospital ran out, LyBurtus asked for an ambulance to take Noah home, fearful of driving him herself.

In May, the month Noah turned 14, LyBurtus heard the regional center had found a place for Noah: a four-bed facility in Rio Linda, a tiny town near Sacramento that she’d never heard of. He could live there for more than a year, she was told, and then hopefully return home with the right support.

Christine LyBurtus shows photographs to Noah.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

But LyBurtus fretted about what she would do if something happened to him so far away. She felt, she said, like she had failed her child. Months passed as they waited for a spot there; LyBurtus said she was told they were trying to hire the needed staff.

“I don’t want him to go,” she said, “but I don’t want to continue going on the way that we’re going on.”

Then in August, LyBurtus was told the regional center had found a spot at a facility much closer to home: the state-run South STAR facility in Costa Mesa, about 20 miles from their apartment. Noah would occupy one of only 15 STAR beds across the state for developmentally disabled adolescents in “acute crisis.”

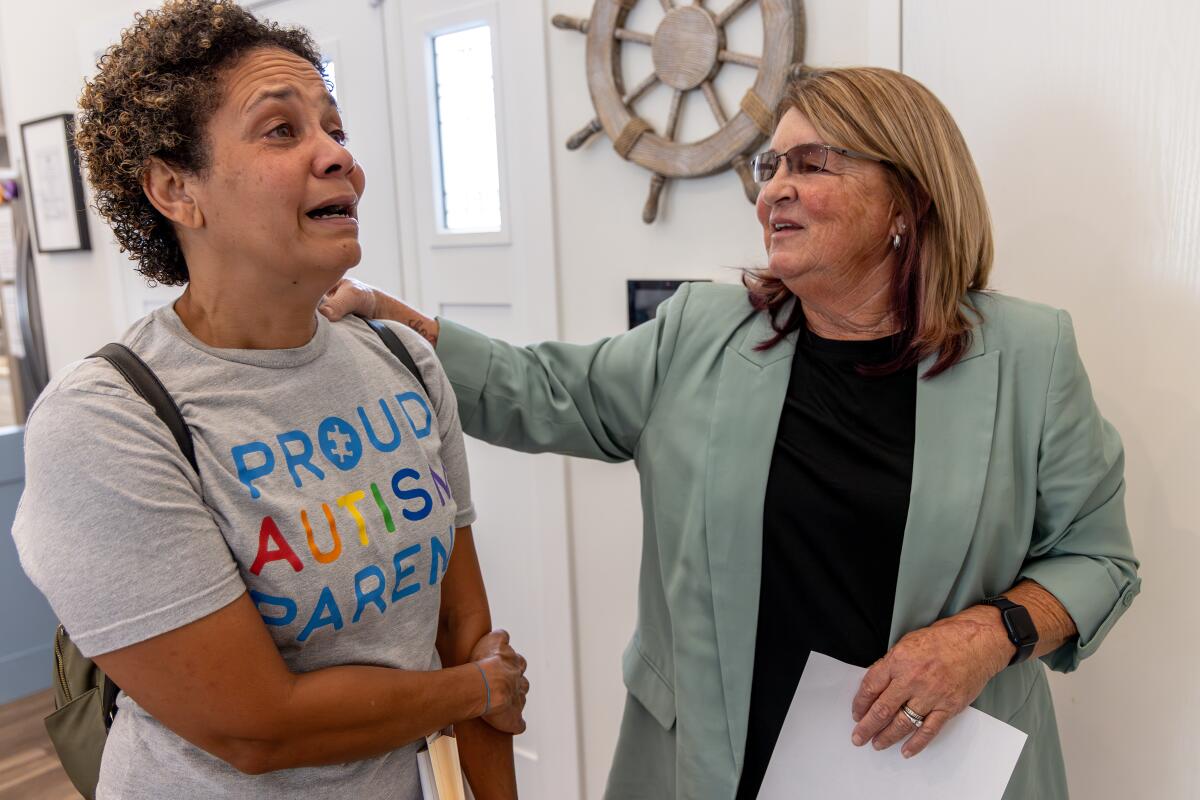

On a bright September morning, LyBurtus pulled up at an unassuming gray house with a “Home Sweet Home” sign by the door. The three teens living there were gone for the morning while an administrator and South STAR program director Kim Hamilton-Royse showed LyBurtus around the house.

Minutes into the tour, LyBurtus found herself crying. Hamilton-Royse stopped her explanation of the daily schedule. “I know this is super hard for you,” she said gently.

But LyBurtus brightened at the sight of the sensory room outfitted with crash pads and a mesmerizing, colorful cylinder of bubbling water. Hamilton-Royse pointed out a vibrating chair and added that they had a projector that would fill the room with illuminated stars.

LyBurtus took photos on her smartphone to show Noah. “You’re not going to be able to get him out of here,” she said.

As they rounded the rest of the house — bedrooms with dressers secured to the wall, a living room with paintings of sailboats, a fish tank — Hamilton-Royse asked if LyBurtus felt any better.

Christine LyBurtus reacts while boxing up items for Noah’s move.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

“I do,” she said. “I just hope that he can behave.”

Hamilton-Royse reassured her that South STAR had never kicked anyone out. “And we’ve had some really challenging folks,” she said.

“I promise you we’ll take very good care of him.”

As she returned to her car, LyBurtus took a deep breath. “It’s hard not to feel like I’m betraying him,” she said, her voice shaking. “But I can’t keep living like this, you know?”

1

2

3

1. Christine Lyburtus tours a residential care facility in Costa Mesa, about 20 minutes from her home. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 2. At the South STAR facility, LyBurtus was told, Noah would occupy one of only 15 STAR beds across the state for developmentally disabled adolescents in “acute crisis.” (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 3. “I just hope that he can behave,” LyBurtus said of son Noah. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Three days later, Noah went back to the Children’s Hospital of Orange County on another psychiatric hold. He came home, then was back in the emergency department a week and a half later.

::

The October night before Noah left home, LyBurtus had brought home sushi for him, one of his favorite foods. He fell asleep around 6:30 p.m, and woke up again at 1 a.m. LyBurtus gave him his medication and as he drifted back to sleep, his mother held him, enjoying the peace.

When he woke up in the morning, she could tell he knew something was up. His clothes had been packed. She’d already shown him photos of the Costa Mesa home and told him, “This is where you’re going. I’m still your mom. I’m still going to go and see you.”

Noah embraces his mother shortly before he was picked up and driven to a residential care facility in Costa Mesa.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

When the black SUV arrived, LyBurtus offered Oreos to coax him into the unfamiliar car. She followed the SUV in her car, staying far enough behind to avoid having Noah see her when he arrived. LyBurtus had been told it would ease the transition.

Back at home, she sank into the bathtub, utterly spent. “I’m going to have to just go with trusting this process as much as I can,” she said, “because I don’t have another choice right now.”

The next day, she met with the South STAR staff to tell them more about Noah. What he likes to eat. What triggers him. His favorite things to do. The Costa Mesa home called whenever staff had physically restrained Noah, but when a weekend passed without a call, she felt some relief.

Lyburtus smiled at the photos and videos sent home: putting together an elaborate stacking toy, washing dishes. It felt like things were going well, LyBurtus said. The staff had scaled back the amount of psychiatric medication he was taking.

But more than a month later, when she first went to visit Noah, he excitedly took her to the front door, as if to say, “Let’s go,” she recalled. She gently told him she was just visiting.

Christine LyBurtus is comforted by caregivers Schahara Zad, left, and Terrence Morris after Noah moved into his residential care facility.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

He led her to the side door instead. She steered him away again. They stepped into the courtyard, and Noah immediately went to the gate to exit.

LyBurtus fell into a funk. As she worried about Noah, she was also figuring out how to make ends meet. With Noah in the Costa Mesa home, Lyburtus was no longer being paid more than $4,000 a month as his caregiver, her sole source of income for years. She tried a number of jobs but ultimately found the work that suited her: caregiving for an elderly woman and children with disabilities.

Her second and third visits with Noah were easier. She snapped photos — Mother and son nestled together on the couch. Noah touching her forehead.

The STAR program runs up to 13 months. As time passed, the regional center had started talking to her about where Noah would go next. LyBurtus was startled.

Wasn’t the plan for him to come home, she asked?

Christine LyBurtus, left, is briefed by Kim Hamilton-Royse while touring a residential care facility for her son.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

That was still on the table, LyBurtus said she was told. But if he wasn’t ready, they didn’t want to wait until the last minute to find somewhere else for Noah, who turned 15 in May.

LyBurtus wanted to block out the idea of him going to another facility.

“I never want to live the way we were living again,” she said.

“But is that worse than him being hours away? I don’t know.”

Science

On a $1 houseboat, one of the Palisades fire’s ‘great underdogs’ fights to stay afloat

Rashi Kaslow sat on the deck of a boat he bought from a friend for just $1 before the fire. After the blaze destroyed his uninsured home in the Palisades Bowl mobile home park — which the owners, to this day, still have not cleared of fire debris — the boat docked in Marina del Rey became his home.

“You either rise from the ashes or you get consumed by them,” he said between tokes from a joint as he watched the sunset with his chihuahua tucked into his tan Patagonia jacket.

“Some people take their own lives,“ he said, musing on the ripple effect of disasters. “After Katrina, a friend of my mom unfortunately did that. … Some people just fall into the bottle.”

The flames burn not only your house, but also your most sacred memories. Among the few items Kaslow managed to save were journals belonging to his late mother, who, in the 1970s, helped start the annual New Orleans Jazz Fest, which is still going strong today.

A disaster like the Palisades fire burns your entire way of life, your community, your sense of self.

The fire put a strain too big to bear on Kaslow’s relationship with his long-term girlfriend. The emotional trauma he experienced forced him to take a break from boat rigging, a dangerous profession he’s practiced for 10 years that requires sharp mental focus as you scale ship masts to wrangle a web of ropes, wires and blocks.

Some days, he feels kind of all right. Others, it’s like he’s drowning in grief. “You try to get back on that horse and do this recovery thing — the recovery dance,” Kaslow said, “which is boring, to say the least.”

Living on a houseboat comes with its own rituals; these largely keep Kaslow occupied. He goes to the boathouse for his ablutions, walks his chihuahua around the marina and rides an electric skateboard into the nearby neighborhoods for a change of scenery.

‘You either rise from the ashes or you get consumed by them.’

— Rashi Kaslow

He’s not yet sure where he’ll end up. Maybe someday the owners of the Palisades Bowl will let him rebuild, but Kaslow is too much of a pragmatist to get his hopes up. Maybe he’ll eventually scrape together enough money to leave the city he’s called home for more than two decades and finally buy a regular old house — not a mobile home, not a boat.

As 2025 slogged on, Kaslow repeatedly watched leaders do little to help. The Los Angeles Fire Department had failed to put out the Lachman fire. Gov. Gavin Newsom’s state park had failed to monitor the burn scar for hotspots. The Los Angeles Department Water and Power had failed to fill the Santa Ynez Reservoir, meant to protect the Pacific Palisades. Police failed to protect his burned lot from looters. Mayor Karen Bass failed to force the owners of the Palisades Bowl to clear the lot of debris.

Kaslow imagines welcoming Bass and Newsom onto his boat — his life now — and sailing out into the sunset. “There should be some accountability,” he said. “I just want to look them in the eyes and ask them, ‘What the f— really happened?’”

Kaslow holds a ceramic vase he recovered from the rubble of his home.

It’s a sentiment shared by many from the Bowl, who Kaslow has dubbed the fire’s “great underdogs.” They’re among the Palisadians who’ve been essentially barred from recovering — be it due to financial constraints, uncooperative landowners or health conditions that make the lingering contamination, with little help from insurance companies to remediate, simply too big a risk.

“I don’t want to be a victim for the rest of my life,” Kaslow said. “I don’t want to let this destroy me anymore than it already has.”

As November’s beaver supermoon rose above the marina, pulling the tide up with it, he felt a glimmer of optimism — a foreign feeling, like reconnecting with an old friend.

Kaslow had received a bit of money from one of the various resident lawsuits against the Palisades Bowl’s owners, as well as a modest housing grant from Neighborhood Housing Services, a local nonprofit, that covered the rent for his spot in the marina.

But a week later, Neighborhood Housing Services ran out of money, and a federal loan that could finally help him to move on from simply trying to stay afloat to charting his future remains far off on the horizon.

Regardless, Kaslow cannot help but feel grateful, despite all he’s lost. He thinks of his elderly neighbors whose entire lives were upended in their final years. Or the kids of nearby Pali High, who pushed their way through the COVID-19 pandemic only to have their school burn in the blaze.

He thinks of the countless people quietly going through their own personal tragedies, without the media attention or outpouring from the greater community or support from the government: A messy divorce that leaves a young mother isolated; a kitchen fire in suburban America that levels a home; an interstate car crash that kills someone’s child.

“You start to appreciate things more, I think, when your whole life is shaken up,” Kaslow said, looking out at the moonlight glimmering across the marina. “That is a blessing.”

Science

A retired teacher found some seahorses off Long Beach. Then he built a secret world for them

Rog Hanson emerges from the coastal waters, pulls a diving regulator out of his mouth and pushes a scuba mask down around his neck.

“Did you see her?” he says. “Did you see Bathsheba?”

On this quiet Wednesday morning, a paddle boarder glides silently through the surf off Long Beach. Two stick-legged whimbrels plunge their long curved beaks into the sand, hunting for crabs.

Classic stories from the Los Angeles Times’ 143-year archive

But Hanson, 68, is enchanted by what lies hidden beneath the water. Today he took a visitor on a tour of the secret world he built from palm fronds and pine branches at the bottom of the bay: his very own seahorse city.

The visitor confirms that she did see Bathsheba, an 11-inch-long orange Pacific seahorse, and a grin spreads across Hanson’s broad face.

“Isn’t she beautiful?” he says. “She’s our supermodel.”

If you get Hanson talking about his seahorses, he’ll tell you exactly how many times he’s seen them (997), who is dating whom, and describe their personalities with intimate familiarity. Bathsheba is stoic, Daphne a runner. Deep Blue is chill.

He will also tell you that getting to know these strange, almost mythical beings has profoundly affected his life.

“I swear, it has made me a better human being,” he says. “On land I’m very C-minus, but underwater, I’m Mensa.”

Hanson is a retired schoolteacher, not a scientist, but experts say he probably has spent more time with Pacific seahorses, also known as Hippocampus ingens, than anyone on Earth.

“To my knowledge, he is the only person tracking ingens directly,” says Amanda Vincent, a professor at the University of British Columbia and director of the marine conservation group Project Seahorse. “Many people love seahorses, but Roger’s absorption with them is definitely distinctive. There’s a degree of warm obsession there, perhaps.”

Rog Hanson keeps watch over a small colony of Pacific seahorses.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

Over the last three years, Hanson has made the two-hour trek from his home in Moreno Valley to the industrial shoreline of Long Beach to visit his “kids” about every five days. To avoid traffic, he often leaves at 2 a.m. and then sleeps in his car when he arrives.

He keeps three tanks of air and his scuba gear in the trunk of his 2009 Kia Rio. A toothbrush and a pair of pink leopard print reading glasses rest on the dash.

Hanson makes careful notes after all his dives in a colorful handmade log book he stores in a three-ring binder. On this Wednesday he dutifully records the water temperature (62 degrees), the length of the dive (58 minutes), the greatest depth (15 feet) and visibility (3 feet), as well as the precise location of each seahorse. His notes also include phase of the moon, the tidal currents and the strength of the UV rays.

“Scientists will tell you that sunlight is an important statistic to keep down,” he says.

He has given each of his four seahorses a unique logo that he draws with markers in his log book. Bathsheba’s is a purple star outlined in red, Daphne’s is a brown striped star in a yellow circle.

Rog Hanson makes careful notes after all his dives. He has given each of his four seahorses a unique logo.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

He’s learned that the seahorses don’t like it when he hovers nearby for too long. Now he limits his interactions with them to 15 to 30 seconds at a time.

“At first I bugged them too much,” he says. “I was the paparazzi swimming around.”

Hanson traces the origins of his seahorse story back nearly two decades to the early morning of Dec. 30, 2000.

He was diving solo off Shaw’s Cove in Laguna Beach when a slow-moving giant emerged from the abyss. It was a gray whale whose 40-foot frame cast Hanson in shadow.

The whale could have killed him with a flick of its tail, Hanson says, but he felt no fear. The two made eye contact and, as Hanson tells it, he felt the whale’s gaze peering directly into his soul.

It was all over in 10 seconds, but Hanson was altered. He had always wanted to live at the beach, but after this encounter, he vowed to make it happen. It took years —15, in fact — but he finally got a job as a special education teacher in the Long Beach public school system. He bought a van and parked it on Ocean Boulevard. He lived at the beach and dived every day for 3½ months before moving to Moreno Valley.

To amuse himself while he lived at the beach, he built an underwater city he called Littleville out of discarded toys he found at the bottom of the bay.

Hanson saw his first seahorse in January 2016 while checking on Littleville. It was bright orange, just 4.5 inches long, and Hanson, who had logged over a thousand dives in the area, knew it didn’t belong there.

Daphne is one of the seahorses that Rog Hanson is studying in Alamitos Bay.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

The range of the Pacific seahorse is generally thought to extend from Peru to as far north as San Diego. This seahorse ended up about 100 miles north of that.

Scientists said the seahorse and others that joined her had probably ridden an unusual pulse of warm water up the coast, along with other animals generally found in southern waters.

“We were getting a lot of weird sightings in the fall of 2015,” says Sandy Trautwein, vice president of husbandry at the Aquarium of the Pacific. “There was a yellow-bellied sea snake, bluefin tuna, marlin, whale sharks — a lot of animals associated with warm water.”

Most of these animals eventually left after ocean temperatures returned to normal, but Hanson’s seahorses stayed.

That may be because Hanson had built them a home.

It happened like this: In June 2016 he watched in horror as more than 100 high school football players splashed in the shallow waters, right where his seahorses usually hung out.

“I thought, I gotta do something, I gotta do something,” he says.

“On land I’m very C-minus, but underwater, I’m Mensa.”

— Rog Hanson

Then he remembered that, back in the Midwest where he grew up, he used to help the city park service make “fish cribs.” In early spring they would use brush and twigs to build what looked like a miniature log cabin with no roof on an ice-covered lake. When the ice melted, the cribs would fall to the bottom, creating a habitat for fish and other animals.

“So I said to myself, build them a city that’s deeper, where feet can’t get to it even at low tide,” Hanson says.

And he did.

By July 2016 two pairs of seahorses had moved into the new habitat. Daphne, the runner, was named after the nymph from Greek mythology who flees Apollo, Kenny’s name came from the proprietor of a local kayaking company. “Bathsheba” was inspired by a Bible story, and her mate, Deep Blue, named after a dive shop that has helped sponsor Hanson’s work since he launched his seahorse study.

He’s seen Kenny’s and Deep Blue’s bellies swell with pregnancy and noted how their partners check in on them daily, frequently standing sentinel nearby. He’s visited the fish at odd hours to see how their behavior changes from morning to night. And he mourned when Kenny disappeared in January. He still hasn’t come back. (A new member, CD Street, arrived June 29.)

“It feels like I’m reading a book, the book of their life, and I can’t put it down,” he says.

He’s also reached out to seahorse scientists across the globe to compare notes. “I won’t say I know the most about seahorses in the world, but I know the people who do,” he says.

Amanda Vincent, the director of Project Seahorse, says that seahorses spark an emotional reaction in almost everyone.

Daphne is one of the seahorses that Rog Hanson is studying in Alamitos Bay. Hanson and Ashley Arnold keep watch over a small colony of Pacific seahorses.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

“Remember those books with three flaps where you can mix the head of a giraffe with the body of a snake and the tail of a monkey? That’s what we’ve got here,” she says. “They appeal to the sense of fancy and wonder in us.”

When Mark Showalter, a planetary astronomer at the SETI Institute, recently discovered a moon orbiting Neptune, he named it Hippocamp in part because of his love of seahorses.

“I’ve seen them in the wild and they are marvelously strange and interesting,” he says. “It’s a fish, but it doesn’t look anything like a fish.”

Pacific seahorses are among the largest members of the seahorse family. Males can grow up to 14 inches long, while females generally top out at about 11. They come in a variety of colors, including orange, maroon, brown and yellow. They are talented camouflagers that can alter the color of their exoskeleton to blend into their environment.

“I won’t say I know the most about seahorses in the world, but I know the people who do.”

But perhaps their most distinguishing characteristic is that they are the only known species in the animal kingdom to exhibit a true male pregnancy. Females deposit up to 1,500 eggs in the male’s pouch. The males incubate the eggs, providing nutrition and oxygen for the growing embryos. When the larval seahorses are ready to be released, he goes into labor — scientists call it “jackknifing” — pushing his trunk toward his tail.

After three years of observation, Hanson has collected new evidence about seahorse mating practices. His research suggests that although most seahorses are monogamous, a female will mate with two males if there are no other female seahorses around.

He also found that males, who are in an almost constant state of pregnancy, tend to stick to an area about the size of a king-size mattress, while the females roam up to 150 feet from their home during a typical day.

Eventually, he may be able to help scientists answer another long-standing question: What is the lifespan of Pacific seahorses in the wild? Some researchers say about five years; others think it could be up to 12.

“It will be interesting to see what Roger finds out,” Vincent says.

In June 2017, about one year after Hanson began formally tracking the seahorses, he took on a partner: a young scuba instructor named Ashley Arnold.

Arnold, who has short red hair and a jocular vibe, is a former Army staff sergeant who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. She learned to dive as part of a program the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs hospital offered to female veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and military sexual trauma. Arnold suffered from both. Diving became her salvation.

Dive instructor Ashley Arnold is a former Army staff sergeant who says that diving at least twice a week helps her deal with PTSD and MST.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

“All the irritation on the surface disappears when you go under the water,” she says. “It’s like, ‘What was I concerned about?’ You forget about everything else. Nothing else matters.”

She used her GI Bill to pay for a scuba instructor course and to set up her own business. Now, she finds that if she dives at least twice a week and has a dog, she does not need to take medication.

“All the irritation on the surface disappears when you go under the water.”

— Ashley Arnold

“That’s a pretty big statement in my opinion,” she says.

Arnold and Hanson met in June 2016 on a dive trip to Catalina. Hanson mentioned his seahorses. Arnold was intrigued, but still lived in Salt Lake City.

One year later, Arnold moved to Huntington Beach and gave Hanson a call.

“I said, ‘Hey Roger, let’s chat. Any chance I could join you at the seahorses you talked about?’” she says. “And he decided I was acceptable.”

Now, Arnold and her boyfriend, Jake Fitzgerald, check in on the seahorses about once a week and help Roger rebuild the city he created for them.

Rog Hanson, 68, teamed up with dive instructor Ashley Arnold two years ago to keep watch over a small colony of Pacific seahorses.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

“We call them our kids because we love them so much,” Arnold says.

Hanson and Arnold are very protective of their seahorse family. They tell visitors to remove GPS tags from their photos. They swear them to secrecy.

There is little chance anyone would find Hanson’s seahorses without a guide. Also, diving in these waters off Long Beach can be a challenge.

The water is shallow. It’s hard to get your buoyancy right. A misplaced flipper kick can stir up blinding sand and silt.

But if Hanson wants to show you his underwater world, nothing will stop him. He will hold you firmly by the hand and guide you down to the forest he built at the bottom of the bay.

Ashley Arnold, right, gets rinsed off with a hose by Rog Hanson after a dive Alamitos Bay.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

He will use a plastic tent stake, jabbing it into the bottom to propel himself — and you holding on — across the ocean floor. When he spots a seahorse he will use the stake as a pointer. Through the murky water you strain to see. Then it appears.

Orange and rigid. Thin snout. Bony plates. Stripes down the torso. Totally still.

And if you’ve never seen a seahorse in the wild before, you will feel honored and awed, as if you’ve just seen a unicorn beneath the sea.

Science

California’s summer COVID wave shows signs of waning. What are the numbers in your community?

There are some encouraging signs that California’s summer COVID wave might be leveling off.

That’s not to say the seasonal spike is in the rearview mirror just yet, however. Coronavirus levels in California’s wastewater remain “very high,” according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as they are in much of the country.

But while some COVID indicators are rising in the Golden State, others are starting to fall — a hint that the summer wave may soon start to decline.

Statewide, the rate at which coronavirus lab tests are coming back positive was 11.72% for the week that ended Sept. 6, the highest so far this season, and up from 10.8% the prior week. Still, viral levels in wastewater are significantly lower than during last summer’s peak.

The latest COVID hospital admission rate was 3.9 hospitalizations for every 100,000 residents. That’s a slight decline from 4.14 the prior week. Overall, COVID hospitalizations remain low statewide, particularly compared with earlier surges.

The number of newly admitted COVID hospital patients has declined slightly in Los Angeles County and Santa Clara County, but ticked up slightly up in Orange County. In San Francisco, some doctors believe the summer COVID wave is cresting.

“There are a few more people in the hospitals, but I think it’s less than last summer,” said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a UC San Francisco infectious diseases expert. “I feel like we are at a plateau.”

Those who are being hospitalized tend to be older people who didn’t get immunized against COVID within the last year, Chin-Hong said, and some have a secondary infection known as superimposed bacterial pneumonia.

Los Angeles County

In L.A. County, there are hints that COVID activity is either peaking or starting to decline. Viral levels in local wastewater are still rising, but the test positivity rate is declining.

For the week that ended Sept. 6, 12.2% of wastewater samples tested for COVID in the county were positive, down from 15.9% the prior week.

“Many indicators of COVID-19 activity in L.A. County declined in this week’s data,” the L.A. County Department of Public Health told The Times on Friday. “While it’s too early to know if we have passed the summer peak of COVID-19 activity this season, this suggests community transmission is slowing.”

Orange County

In Orange County, “we appear to be in the middle of a wave right now,” said Dr. Christopher Zimmerman, deputy medical director of the county’s Communicable Disease Control Division.

The test positivity rate has plateaued in recent weeks — it was 15.3% for the week that ended Sept. 6, up from 12.9% the prior week, but down from 17.9% the week before that.

COVID is still prompting people to seek urgent medical care, however. Countywide, 2.9% of emergency room visits were for COVID-like illness for the week that ended Sept. 6, the highest level this year, and up from 2.6% for the week that ended Aug. 30.

San Diego County

For the week that ended Sept. 6, 14.1% of coronavirus lab tests in San Diego County were positive for infection. That’s down from 15.5% the prior week, and 16.1% for the week that ended Aug. 23.

Ventura County

COVID is also still sending people to the emergency room in Ventura County. Countywide, 1.73% of ER patients for the week that ended Sept. 12 were there to seek treatment for COVID, up from 1.46% the prior week.

San Francisco

In San Francisco, the test positivity rate was 7.5% for the week that ended Sept. 7, down from 8.4% for the week that ended Aug. 31.

“COVID-19 activity in San Francisco remains elevated, but not as high as the previous summer’s peaks,” the local Department of Public Health said.

Silicon Valley

In Santa Clara County, the coronavirus remains at a “high” level in the sewershed of San José and Palo Alto.

Roughly 1.3% of ER visits for the week that ended Sunday were attributed to COVID in Santa Clara County, down from the prior week’s figure of 2%.

-

Iowa2 days ago

Iowa2 days agoAddy Brown motivated to step up in Audi Crooks’ absence vs. UNI

-

Washington1 week ago

Washington1 week agoLIVE UPDATES: Mudslide, road closures across Western Washington

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoMatt Campbell reportedly bringing longtime Iowa State staffer to Penn State as 1st hire

-

Iowa4 days ago

Iowa4 days agoHow much snow did Iowa get? See Iowa’s latest snowfall totals

-

Cleveland, OH1 week ago

Cleveland, OH1 week agoMan shot, killed at downtown Cleveland nightclub: EMS

-

World1 week ago

Chiefs’ offensive line woes deepen as Wanya Morris exits with knee injury against Texans

-

Maine20 hours ago

Maine20 hours agoElementary-aged student killed in school bus crash in southern Maine

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoThe Game Awards are losing their luster