Science

An essential medical device fails people of color. A clinic is suing to fix that

Roots Community Health Center was slammed in 2020, with lines for its COVID-19 testing stations stretching around the block and exam rooms full of people struggling to breathe.

Patient after patient at the East Oakland clinic extended their fingers so that healthcare workers could clip on a pulse oximeter, a device that measures the degree to which red blood cells are saturated with oxygen. For healthy people, a normal “pulse ox” reading is typically between 95% and 100%.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had instructed providers to give oxygen therapy to any COVID patient with a pulse oximeter reading below 90%. Like their counterparts around the country, Roots doctors advised concerned patients to buy inexpensive pulse oximeters so they could monitor their levels at home.

As the pandemic ground on, it became clear that Black and brown patients were dying of COVID at disproportionately high rates, both across the U.S. and in Roots’ own Alameda County.

In the rare hour when she wasn’t in the clinic, Roots founder and Chief Executive Dr. Noha Aboelata paged through medical research in search of answers that might help her patients, the vast majority of whom were Black or brown.

One paper in the New England Journal of Medicine stopped her cold. University of Michigan researchers examined records of thousands of hospitalized COVID patients and looked for instances of “occult hypoxia” — a situation when a patient’s pulse oximeter reads in the healthy range, but their actual blood oxygen levels are dangerously low. The researchers found that this happened to Black patients nearly three times as often as it did to white patients.

Dr. Noha Aboelata said it was “devastating” to realize that researchers had known for years that patients with dark skin were more likely to get false readings from pulse oximeters.

(Carolyn Fong)

Aboelata recalled the “devastating feeling” of diving further into the literature and realizing that this disparity was not a new discovery.

Research dating back to 1990 found that inaccurate pulse oximeter readings were more common in Black patients than non-Black ones. In 2005, detailed lab experiments showed that pulse oximeters frequently overestimated blood oxygen levels in patients with more skin pigmentation.

“This device is really used almost like a vital sign, like you would use a blood pressure cuff,” Aboelata recalled. “How horrified you would feel if you suddenly found out that your blood pressure cuff didn’t work on a certain demographic of your patients?”

She alerted colleagues to the findings and investigated the effect the devices had on the fates of COVID patients of color. She asked the Food and Drug Administration to require pulse oximeter makers to test their devices on people of color and to warn consumers about the heightened risk of false readings. Attorneys for Roots sent letters to companies that made or sold pulse oximeters in California asking them to improve their products and disclose their limitations.

When little changed, Roots filed a lawsuit in November against CVS, Walgreens, GE Healthcare and nine other companies that make, sell or distribute pulse oximeters in California.

“The pigmentation-derived inaccuracies of pulse oximeter readings in people with darker skin consistently skew — or are biased — in one dangerous direction: showing that their blood is more oxygenated than it is in reality,” the lawsuit states. “Individuals with darker skin who use the devices are no less entitled to accurate readings than individuals with lighter skin.”

The suit asks that the companies either find a fix or place warning labels on the products to alert users that skin pigment may affect results.

Before pulse oximeters were widely adopted in the 1980s, the only way to gauge a patient’s blood oxygen saturation was to draw a sample of blood from their arterial vein, a painful procedure that had to be followed by immediate laboratory analysis. The portable, noninvasive oximeters were “a true innovation,” said Dr. Phil Bickler, a neuroanesthesiologist who directs the Hypoxia Research Laboratory at UC San Francisco.

“It’s arguably one of the most important clinical monitors ever devised,” Bickler said, second only to the thermometer.

Clinical research coordinator René Vargas Zamora opens a drawer of pulse oximeters at UC San Francisco’s Hypoxia Lab.

(Corinne Purtill/Los Angeles Times)

A pulse oximeter works by shining a light that passes through skin, blood and tissues in the finger and then measuring how much light comes out the other side.

Oxygen-rich blood absorbs more infrared light. So does melanin, the pigment that helps determine skin, hair and eye color. As a result, patients with darker skin tones are more likely to get pulse oximeter readings that show their blood oxygen saturation to be higher than it actually is.

Skin pigment isn’t the only variable that can skew those results. Cold hands, trembling fingers, incorrect probe placement, even nail polish can throw a reading off by a few percentage points too. Knowing this, doctors traditionally used the pulse ox as one data point among many when determining a patient’s course of treatment.

Then COVID-19 hit. As emergency rooms filled and oxygen tanks grew scarce, the CDC anointed pulse oximeter readings as the official standard in its guidelines for COVID care: Below 90%, the patient should be started on oxygen therapy. Above that, it was the doctor’s call.

As the sheer volume of patients grew, so did the number of people with occult hypoxia. Their pulse ox readings were 92% or higher, yet they often had shortness of breath, erratic heartbeats, headaches, confusion and other symptoms of low oxygen saturation.

Many providers around the country also noted that patients with occult hypoxia were more likely to have darker-toned skin.

“Honestly, we had no idea what to make of it,” said Dr. Michael Sjoding, a pulmonologist at the University of Michigan.

He and his colleagues initially wondered whether something about the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself made it harder to detect hypoxia.

Then Sjoding came across an article by Amy Moran-Thomas, a medical anthropologist at MIT. After spending sleepless nights monitoring her husband’s pulse oximeter readings as he suffered through COVID, Moran-Thomas began digging into the history of the device.

She found the 1990 paper that noted hypoxic Black patients were more likely to get deceptively high readings. She found the 2005 study from Bickler’s lab noting the devices were more likely to overestimate oxygen saturation in patients with dark skin than in those with light skin, results the lab confirmed in a follow-up study two years later.

“I was shocked, because I’m a pulmonary critical care physician, I’m a lung doctor, and I didn’t know this whole literature,” Sjoding said.

He and his colleagues pulled data from their own hospital and found Black patients had nearly three times the rate of occult hypoxia as white patients. They published their results in December 2020.

After Aboelata read their paper, she scoured her memory for patients the devices might have betrayed.

She recalled a Black man she had tried to get approved for home oxygen therapy prior to the pandemic. Medicare only paid for the treatment if a patient’s oxygen saturation was below 90%, and “his pulse ox reading just looked too good compared to what I was seeing,” Aboelata said. She sent him to the hospital for an arterial blood gas draw. Sure enough, his oxygen was low enough to qualify.

Patients shared similar stories, “things like, ‘The ambulance didn’t take them to the hospital because they said that their reading was fine,’ or, ‘We were sent home from the emergency department because they said our reading was fine,’” Aboelata said.

In normal times, she said, providers are much more likely to err on the side of caution for a potentially hypoxic patient. But in the worst days of COVID, every bed, oxygen tank and minute was precious. Providers relied on what they believed was the pulse oximeter’s impartial measure to make extremely difficult decisions, unaware that the device did not evaluate all patients equally well.

Aboelata and colleagues from UCSF and Sutter Health’s Institute for Advancing Health Equity published their own study in the American Journal of Epidemiology showing that Black patients whose pulse oximeters overestimated blood oxygen levels waited an extra 4½ hours, on average, to start supplemental oxygen. They were also slightly less likely to be admitted to the hospital or receive oxygen therapy at all.

“There’s just no way to really know how far-reaching this impact is,” Aboelata said. “The likelihood [is] that people were left home to die, or sent home to die.”

In February 2021, the FDA issued a safety notice cautioning users that pulse oximeters can be thrown off by a number of variables, including skin pigment.

The following year, the FDA convened an advisory committee on the topic. The panel recommended the agency demand better consumer labels and more stringent testing from companies seeking approval for their devices.

Currently, the FDA recommends — but doesn’t require — that pulse oximeter makers ensure that in their clinical trials, either two participants or 15% of total participants are “darkly pigmented” people, a definition open to interpretation.

Clinical research coordinator René Vargas Zamora holds up an example of the Monk Skin Tone Scale at UC San Francisco’s Hypoxia Lab.

(Corinne Purtill/Los Angeles Times)

This month, the panel advised the FDA to require that new devices be tested on at least 24 people whose skin tones collectively span the Monk Skin Tone scale, a 10-color palette often used to train artificial intelligences to recognize people of different colors. The proposal would divide the scale into three parts, with each part represented by at least 25% of study participants.

To better understand the relationship between skin pigment and pulse ox accuracy, the FDA funded a study at Bickler’s UCSF lab. Results are expected this summer.

“Some companies have posted data showing good performance with darkly pigmented skin for their devices. But I know that those have been tested under ideal conditions,” said Bickler, whose lab investigates the effects of low oxygen on the human body and the devices that measure it. “When pulse oximeters are used in the real world, conditions are not ideal. People are dehydrated, they’re in shock, they’re moving. There’s all kinds of interference that can happen and that get in the way of good performance.”

For Bickler, it’s gratifying to see the government finally address a problem that has been known for decades but that device manufacturers seemed reluctant to address.

“There’s a lot of inertia and denial in the industry,” he said. “It was an inconvenient problem that could be ignored, up until COVID.”

Dr. Phil Bickler is a neuroanesthesiologist who directs the Hypoxia Research Laboratory at UC San Francisco.

(Corinne Purtill/Los Angeles Times)

The Times reached out to all the defendants being sued by Roots. Those that responded declined to comment on pending litigation.

Only one company has taken actions to address Roots’ concerns. Illinois-based NuvoMed pulled its pulse oximeters from the market in California and agreed to place warning labels on their remaining inventory after receiving Roots’ October letter, said Jonathan Weissglass, the clinic’s attorney.

“Ideally, we’d like the pulse oximeters to be fixed so that the problem doesn’t occur,” Weissglass said. “In the meantime, we feel there needs to be an adequate warning about the inaccuracies for people with darker skin. … We’ve all seen warning labels that say, ‘Pregnant women should consult with a doctor before using’ or something like that. It’s the same basic idea.”

On a recent afternoon at the clinic, medical assistant Evelyn Rivas clipped a pulse oximeter onto Ja-May Scott’s index finger as she checked his vital signs.

The devices are still an important part of Roots’ toolkit. But “we just view it with more suspicion, frankly, in a lot of our patients,” Aboelata said. “We would really like to be equipped with devices that we know can be accurate for all skin tones. And we feel like in 2024, this shouldn’t be too much to ask.”

Science

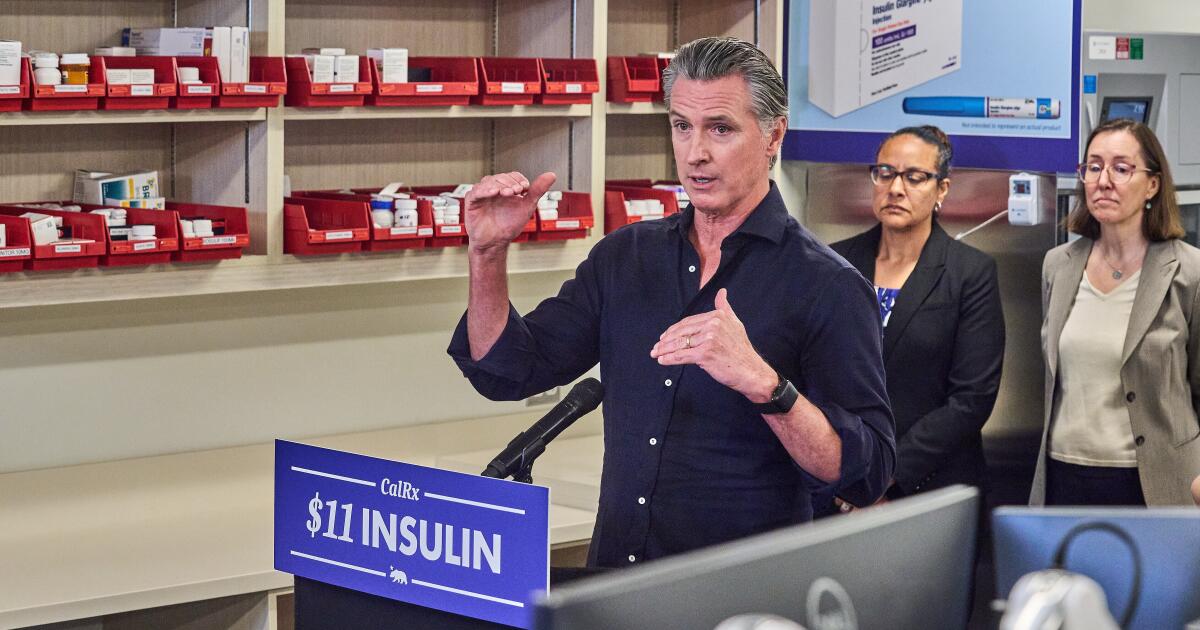

Newsom’s fight with Trump and RFK Jr. on public health

SACRAMENTO — California Gov. Gavin Newsom has positioned himself as a national public health leader by staking out science-backed policies in contrast with the Trump administration.

After Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Susan Monarez for refusing what her lawyers called “the dangerous politicization of science,” Newsom hired her to help modernize California’s public health system. He also gave a job to Debra Houry, the agency’s former chief science and medical officer, who had resigned in protest hours after Monarez’s firing.

Newsom also teamed up with fellow Democratic governors Tina Kotek of Oregon, Bob Ferguson of Washington and Josh Green of Hawaii to form the West Coast Health Alliance, a regional public health agency, whose guidance the governors said would “uphold scientific integrity in public health as Trump destroys” the CDC’s credibility. Newsom argued establishing the independent alliance was vital as Kennedy leads the Trump administration’s rollback of national vaccine recommendations.

More recently, California became the first state to join a global outbreak response network coordinated by the World Health Organization, followed by Illinois and New York. Colorado and Wisconsin signaled they plan to join. They did so after President Trump officially withdrew the United States from the agency on the grounds that it had “strayed from its core mission and has acted contrary to the U.S. interests in protecting the U.S. public on multiple occasions.” Newsom said joining the WHO-led consortium would enable California to respond faster to communicable disease outbreaks and other public health threats.

Although other Democratic governors and public health leaders have openly criticized the federal government, few have been as outspoken as Newsom, who is considering a run for president in 2028 and is in his second and final term as governor. Members of the scientific community have praised his effort to build a public health bulwark against the Trump administration’s slashing of funding and scaling back of vaccine recommendations.

What Newsom is doing “is a great idea,” said Paul Offit, an outspoken critic of Kennedy and a vaccine expert who formerly served on the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory committee but was removed under Trump in 2025.

“Public health has been turned on its head,” Offit said. “We have an anti-vaccine activist and science denialist as the head of U.S. Health and Human Services. It’s dangerous.”

The White House did not respond to questions about Newsom’s stance and Health and Human Services declined requests to interview Kennedy. Instead, federal health officials criticized Democrats broadly, arguing that blue states are participating in fraud and mismanagement of federal funds in public health programs.

Health and Human Services spokesperson Emily Hilliard said the administration is going after “Democrat-run states that pushed unscientific lockdowns, toddler mask mandates, and draconian vaccine passports during the COVID era.” She said those moves have “completely eroded the American people’s trust in public health agencies.”

Public health guided by science

Since Trump returned to office, Newsom has criticized the president and his administration for engineering policies that he sees as an affront to public health and safety, labeling federal leaders as “extremists” trying to “weaponize the CDC and spread misinformation.” He has excoriated federal officials for erroneously linking vaccines to autism, warning that the administration is endangering the lives of infants and young children in scaling back childhood vaccine recommendations. And he argued that the White House is unleashing “chaos” on America’s public health system in backing out of the WHO.

The governor declined an interview request, but Newsom spokesperson Marissa Saldivar said it’s a priority of the governor “to protect public health and provide communities with guidance rooted in science and evidence, not politics and conspiracies.”

The Trump administration’s moves have triggered financial uncertainty that local officials said has reduced morale within public health departments and left states unprepared for disease outbreaks and prevention efforts. The White House last year proposed cutting Health and Human Services spending by $33 billion, including $3.6 billion from the CDC. Congress largely rejected those cuts last month, although funding for programs focusing on social drivers of health, such as access to food, housing and education, were axed.

The Trump administration announced that it would claw back more than $600 million in public health funds from California, Colorado, Illinois and Minnesota, arguing that the Democratic-led states were funding “woke” initiatives that didn’t reflect White House priorities. Within days, the states sued and a judge temporarily blocked the cut.

“They keep suddenly canceling grants and then it gets overturned in court,” said Kat DeBurgh, executive director of the Health Officers Assn. of California. “A lot of the damage is already done because counties already stopped doing the work.”

Federal funding has accounted for more than half of state and local health department budgets nationwide, with money going toward fighting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, preventing chronic diseases, and boosting public health preparedness and communicable disease response, according to a 2025 analysis by KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

Federal funds account for $2.4 billion of California’s $5.3-billion public health budget, making it difficult for Newsom and state lawmakers to backfill potential cuts. That money helps fund state operations and is vital for local health departments.

Funding cuts hurt all

Los Angeles County public health director Barbara Ferrer said if the federal government is allowed to cut that $600 million, the county of nearly 10 million residents would lose an estimated $84 million over the next two years, in addition to other grants for prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Ferrer said the county depends on nearly $1 billion in federal funding annually to track and prevent communicable diseases and combat chronic health conditions, including diabetes and high blood pressure. Already, the county has announced the closure of seven public health clinics that provided vaccinations and disease testing, largely because of funding losses tied to federal grant cuts.

“It’s an ill-informed strategy,” Ferrer said. “Public health doesn’t care whether your political affiliation is Republican or Democrat. It doesn’t care about your immigration status or sexual orientation. Public health has to be available for everyone.”

A single case of measles requires public health workers to track down 200 potential contacts, Ferrer said.

The U.S. eliminated measles in 2000 but is close to losing that status as a result of vaccine skepticism and misinformation spread by vaccine critics. The U.S. had 2,281 confirmed cases last year, the most since 1991, with 93% in people who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown. This year, the highly contagious disease has been reported at schools, airports and Disneyland.

Public health officials hope the West Coast Health Alliance can help counteract Trump by building trust through evidence-based public health guidance.

“What we’re seeing from the federal government is partisan politics at its worst and retaliation for policy differences, and it puts at extraordinary risk the health and well-being of the American people,” said Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Assn., a coalition of public health professionals.

Robust vaccine schedule

Erica Pan, California’s top public health officer and director of the state Department of Public Health, said the West Coast Health Alliance is defending science by recommending a more robust vaccine schedule than the federal government. California is part of a coalition suing the Trump administration over its decision to rescind recommendations for seven childhood vaccines, including for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, influenza and COVID-19.

Pan expressed deep concern about the state of public health, particularly the uptick in measles. “We’re sliding backwards,” Pan said of immunizations.

Sarah Kemble, Hawaii’s state epidemiologist, said Hawaii joined the alliance after hearing from pro-vaccine residents who wanted assurance that they would have access to vaccines.

“We were getting a lot of questions and anxiety from people who did understand science-based recommendations but were wondering, ‘Am I still going to be able to go get my shot?’” Kemble said.

Other states led mostly by Democrats have also formed alliances, with Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and several other East Coast states banding together to create the Northeast Public Health Collaborative.

Hilliard, of Health and Human Services, said that even as Democratic governors establish vaccine advisory coalitions, the federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices “remains the scientific body guiding immunization recommendations in this country, and HHS will ensure policy is based on rigorous evidence and gold standard science, not the failed politics of the pandemic.”

Influencing red states

Newsom, for his part, has approved a recurring annual infusion of nearly $300 million to support the state Department of Public Health, as well as the 61 local public health agencies across California, and last year signed a bill authorizing the state to issue its own immunization guidance. It requires health insurers in California to provide patient coverage for vaccinations the state recommends even if the federal government doesn’t.

Jeffrey Singer, a doctor and senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, said decentralization can be beneficial. That’s because local media campaigns that reflect different political ideologies and community priorities may have a better chance of influencing the public.

A KFF analysis found some red states are joining blue states in decoupling their vaccine recommendations from the federal government’s. Singer said some doctors in his home state of Arizona are looking to more liberal California for vaccine recommendations.

“Science is never settled, and there are a lot of areas of this country where there are differences of opinion,” Singer said. “This can help us challenge our assumptions and learn.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.

Science

How Rising Home Insurance Costs Are Linked to Credit Scores

Two friends bought nearly identical homes last year, in the same northern Minnesota neighborhood, for the same price.

But Tara Novak pays more than twice as much for home insurance as Petra Rodriguez. The only difference? Ms. Novak has a lower credit score.

Across the country, people with weaker credit histories are paying far more for home insurance than owners with spotless records.

Where the home insurance rate gap between “fair” and “excellent” credit is higher

Home insurance premiums have risen rapidly in recent years, fueled by climate change, building costs and inflation. The price shock has rippled into the real estate market, dragging down home prices in areas vulnerable to disasters and leading insurers to abandon homeowners in risky places.

But these dynamics obscure another problem: The home insurance market has cleaved in two along a boundary defined more by a customer’s personal history than by the risk of a disaster hitting their home.

Americans with weaker credit histories, usually from missed payments or high amounts of debt, now pay significantly more for insurance, regardless of where they live, two new studies have found. While those with poor credit histories often can’t purchase homes at all, people with “fair” scores, which range from around 580 to 669, are paying twice as much in some places as people with “excellent” scores of about 800 or higher. And the gap is growing.

Insurers use a metric based on credit history known as an insurance score to set rates, and the figure tracks closely with a customer’s credit score.

The penalty for having a “fair” credit history versus an “excellent” one

States with the biggest pricing gaps

That can mean owners of identical homes, like Ms. Novak and Ms. Rodriguez, pay wildly different rates to insure them. For most people, it’s now just as expensive to have a credit score of “fair” as it is to live in an area likely to experience a disaster like a hurricane or wildfire. About 29 percent of consumers have credit scores that are categorized as “fair” or “poor.”

“There’s so many reasons people have bad credit,” Ms. Novak said. “It’s not like I’ve ever not paid a bill on time. I’m a stickler on my bills, I’m a stickler on my rent, never been late. This is not fair.”

“The choice to use credit scores in pricing means that those lower-credit home owners in risky areas are effectively subsidizing more affluent high-credit homeowners who also live in risky areas,” said Nick Graetz, assistant professor of sociology at the University for Minnesota, who wrote one of the recent papers. “So in a lot of ways, you can keep your insurance price down if you’re high income, high credit — even if you live on the coast of Florida.”

A handful of states have banned insurers from using credit data because of concerns about fairness and the potential for discrimination against low-income people and people of color, but the majority allow it.

For those with both weaker credit and high disaster risk, the combination can set them up for a downward spiral: disasters tend to be followed by decreases in credit scores as people use credit cards and bank loans to recover. That can lead to higher insurance rates, pushing monthly housing costs further out of reach.

“When a disaster hits, there’s a loss of income that occurs, and then that can impact someone’s credit score because they can’t pay their debt, they can’t pay their rent, they can’t pay their mortgage,” said Lance Triggs, executive vice president at Operation HOPE, a financial literacy nonprofit. “And now they’re faced with higher insurance premiums post-disaster.”

A working paper released today by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that homeowners with the lowest credit scores paid, on average, $550 more in 2024 for home insurance than those with the highest scores.

The findings broadly track with data from Quadrant Information Services analyzed by The New York Times, which found that, on average, lower credit scores meant higher premiums across every state that allowed the practice. Dr. Graetz used the same data set for his research, which he did in collaboration with the Consumer Federation of America and the Climate and Community Institute.

When a windstorm last year hit the home of Audrey Thayer, a city council member in Bemidji, Minn., it ripped the siding off her house and stripped shingles from her roof.

Ms. Thayer’s insurance did not cover all the damage. As she fought her insurer for more money, she opened new credit cards and bank loans to repair her home. Her credit score dropped as she tried to find a new insurance plan.

Ms. Thayer, a member of the White Earth Nation, said she was not aware that her credit score could affect her home insurance rates, even though she teaches about credit ratings at a nearby tribal college. “Most of the folks here do not have good credit,” said Ms. Thayer, whose community is one of the poorest in the state. “I did not know what a credit score was until I was 35 or so.”

In Texas, the advocacy group Texas Appleseed found that some insurers charge people with poor credit up to 12 times as much as people with excellent credit for certain policies, said Ann Baddour, the director of the nonprofit’s Fair Financial Services Project.

Higher costs have serious implications for low-income homeowners who live in the path of hurricanes, said Nadia Erosa, the operations manager at Come Dream Come Build, a nonprofit community housing development organization. After the Brownsville, Texas, region saw intense flooding last spring, some residents turned to companies offering high-interest loans to fund repairs, she said, raising the risk of the disaster-credit spiral.

“Delinquencies are going up because people cannot afford their payment,” she said.

The price of risk

Before they can get a mortgage, homebuyers are usually required by lenders to purchase home insurance.

“Households with insurance have fewer financial burdens, fewer unmet needs, they recover faster, they’re more likely to rebuild,” said Carolyn Kousky, an economist and founder of Insurance for Good, a nonprofit that focuses on finding new approaches to risk management. “Yet the people who need insurance the most are the least able to afford it.”

Insurance companies consider a variety of factors when setting the premium for a property. They might examine the age of the roof, or the area’s vulnerability to hurricanes or wildfires. They factor in how much it would cost to rebuild the house if it were damaged.

Insurers have argued that credit history is also worth considering because people with low scores tend to file more claims than those with excellent scores, an assertion that is backed up by the working paper published in the National Bureau of Economic Research today. This likely happens because people with weaker credit histories tend to have less income, and when their home is damaged, they file insurance claims for smaller fixes that a wealthier homeowner might pay for out of pocket.

Paul Tetrault, senior director at the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, a trade organization, said credit scores are a valid way to price premiums.

But others argue that using credit information to price insurance doesn’t make sense.

Because a homeowner pays for insurance upfront, “it’s not like you’re really extending a loan to the customer where you would be worried about the risk of repayment,” Ms. Kousky said. She points out that insurance companies can opt not to renew a homeowner’s policy if they believe it is too risky — a tactic they have been using with increasing frequency.

The NBER analysis found that homeowners who want to pay less for insurance should pay off debt to raise their credit score rather than replace roofs and make other improvements to avoid damage when disaster strikes.

Others believe that even if credit scores are accurate predictors of future claims, they shouldn’t be used to set premiums because that can perpetuate or worsen disparities. For example, people in their mid-20s who are Black, low-income, or grow up in impoverished regions have significantly lower credit scores than their peers, a July working paper from Opportunity Insights, a not-for-profit organization at Harvard University, found.

“When the government and the financial system mandate that we buy a product, there’s a special obligation to make sure the pricing is fair,” said Doug Heller, director of insurance at the Consumer Federation. “To me that is an absolutely solid reason, just like we don’t allow pricing based on race or income or ethnicity or religion.”

A natural experiment

A handful of states, including California and Massachusetts, have banned or limited the use of credit scores in setting home insurance premiums, despite opposition from the insurance industry.

In Nevada, where a temporary pandemic-related rule prevented insurers from using credit history to increase premiums for existing customers from 2020 to 2024, companies refunded approximately $27 million to nearly 200,000 policyholders, said Drew Pearson, a spokesman for the Nevada Division of Insurance.

Perhaps the clearest example of the effects of these bans comes from Washington State, which banned the use of credit information in setting home insurance premiums starting in June 2021. The rule immediately faced legal challenges, and was in effect for just a few months until it was overturned in court.

But the episode allowed researchers to evaluate the effect of credit factors on insurance premiums. When the rule took effect, people with the lowest credit scores saw a decrease in premiums of about $175 annually while those with the highest scores saw an increase of about $100, the NBER analysis found.

“We could see the dynamics of insurance pricing for the same households over time,” said Benjamin Keys, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, who co-authored the paper.

What homeowners paid before and after a ban on credit-based pricing in Washington State

Values compared with premiums paid by homeowners with “medium” credit scores (717 to 756)

In Minnesota, where Tara Novak, Petra Rodriguez and Audrey Thayer live, a state task force looked at ways to lower insurance costs for residents. It recently considered a ban or limit on the use of credit scores to set rates, but did not move forward with a recommendation.

Ms. Rodriguez said she doesn’t think it’s fair that her friend Ms. Novak should have to pay so much more for insurance to live in an identical house.

A credit score doesn’t capture anything about a person’s habits, or what they’re like as a tenant, or even years of on-time rent payments, she said. “It’s not who you are,” she said.

Methodology

Home insurance policy rates were supplied by Quadrant Information Services, an insurance data solutions company. The rates shown are representative of publicly sourced filings and should not be interpreted as bindable quotes. Actual individual premiums may vary.

‘States with the biggest pricing gaps’Rates shown are based on a home insurance policy with $400,000 of dwelling coverage and a $100,000 liability limit on a new home, for a homeowner age 50 or younger. Rates are averaged for all the individual company filings represented in the sample, which add up to a majority of the market share in each state but do not cover all active insurers in the state. Rates are also averaged to the state level from zip code level data.

‘The credit penalty in each state’Each insurance company incorporates credit history information differently, often using proprietary methods, so the scores do not map directly to FICO credit scores.

‘What homeowners paid before and after a ban on credit-based pricing in Washington State’Data shown are based on observations of real home insurance policies and homeowner credit scores from ICE McDash analyzed by the researchers of Blonz, Hossain, Keys, Mulder and Weill (2026). The price comparisons across credit score tiers controlled for variance in disaster risk, insurance policy characteristics, geography, and other year to year fluctuations.

Science

Earth is warming faster than previously estimated, new study shows

Planetary warming has significantly accelerated over the past 10 years, with temperatures rising at a higher rate since 2015 than in any previous decade on record, a new study showed.

The Earth warmed around 0.35 degrees Celsius in the decade to 2025, compared to just under 0.2C per decade on average between 1970 and 2015, according to a paper published on Friday in the scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters. This is the first statistically significant evidence of an acceleration of global warming, the authors said.

The past three years have been the hottest on record, compared to the average before the Industrial Revolution. In 2024, warming went past 1.5C, the lower limit set by the Paris Agreement. That target refers to temperature increases over 20 years, but breaching it for one year shows efforts to slow down climate change have been insufficient, the scientists who wrote the new paper said.

The findings shed light on an ongoing debate among researchers. While there is consensus that greenhouse gas emissions have caused the planet to heat up since pre-industrial times, that warming had been steady for decades. But record-breaking temperatures in recent years have led scientists to question whether the pace of temperature gains is accelerating.

Demonstrating that was difficult due to natural fluctuations in temperatures. The researchers filtered out the “noise” to make the “underlying long-term warming signal” more clearly visible, said Grant Foster, a co-author of the study and a U.S.-based statistics expert.

Researchers isolated phenomena including the El Niño weather phase, volcanic eruptions and solar irradiance. When looking at temperature increases without their influence, the authors concluded the evidence is “strong” that the accelerated warming was not due to an unusually hot 2023 and 2024, but that since 2015 global temperatures departed from their previous, slower path of warming.

The new report adds to a growing body of work that indicates climate change is having a quicker and larger impact on the planet than scientists have understood. A separate paper published this week found that many studies on sea-level increases underestimate how much water along the coast has already risen.

“If the warming rate of the past 10 years continues, it would lead to a long-term exceedance of the 1.5C limit of the Paris Agreement before 2030,” said Stefan Rahmstorf, the lead author of the warming study and a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “How quickly the Earth continues to warm ultimately depends on how rapidly we reduce global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels to zero.”

Millan writes for Bloomberg.

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Pennsylvania5 days ago

Pennsylvania5 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Detroit, MI4 days ago

Detroit, MI4 days agoU.S. Postal Service could run out of money within a year

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death

-

Miami, FL6 days ago

Miami, FL6 days agoCity of Miami celebrates reopening of Flagler Street as part of beautification project