IT’S NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE to propose almost any change at the local level in Massachusetts—a new apartment building, a corner-store zoning variance, even a bicycle lane—without setting off yelps of protest. Though these complaints come in many varieties, a perennial and familiar one is the fear any such change will corrode the “historic character” of the place in question.

For the most unsentimental and pro-development reformers, these concerns are easily brushed aside. After all, these critics might say, how can we possibly elevate historic preservation above all the other goals of land use policy, like affordable housing, the energy transition, or desegregation? In the opinion of someone with an unsparingly future-oriented outlook, the response to a concern about undermining a city or town’s historic character might simply be: too bad.

But let us, for a moment, take the charge seriously. Let’s assume that we do, in fact, want to preserve the unique historic landscapes of the cities and towns in Massachusetts. For me, this isn’t a stretch of the imagination, since I have dedicated much of my professional life to studying the historical geography of New England. Sentimental though the feeling may be, I genuinely love the historic landscapes of my home region: the peaceful symmetry of town commons, the red-brick warrens of mill cities, and so on.

From this point of view, let us try to make a clear-eyed evaluation of the policy solution favored by those who howl against the apartment blocks, the zoning variances, and the bicycle lanes that loom menacingly over the cherished historical integrity of their neighborhoods. “Local control” is the supposed bulwark against these historical violations, for, we are told again and again, the blame lies with non-locals: with developers headquartered in some distance office, with legislators ensconced on Beacon Hill, with urban planners captivated by foreign trends. If only municipalities were allowed to make their own decisions and run their own affairs, if only the residents of a neighborhood were given the autonomy to preserve their own communities, then surely the historic character of our cherished landscapes would be better protected.

How does that assertion hold up under scrutiny? Have local authorities, when protected from the intrusions of meddling outsiders, actually done a better job at preserving their historic landscapes? As it turns out: not really. Sadly, Massachusetts municipalities have rarely been good stewards of their own historical character when given free rein to exercise the powers of their local land-use controls. In fact, the opposite is closer to the truth. For much of the 20th century and still to this day, town-level control of development has been one of the primary culprits of historic destruction.

As just one example, consider the Town of Middleborough, which announced in February that it would ignore the state’s new mandate that municipalities provide zoning for multifamily homes near MBTA stations. The housing law, complained Middleborough in an official statement, “does not take into account the unique characteristics of each community.”

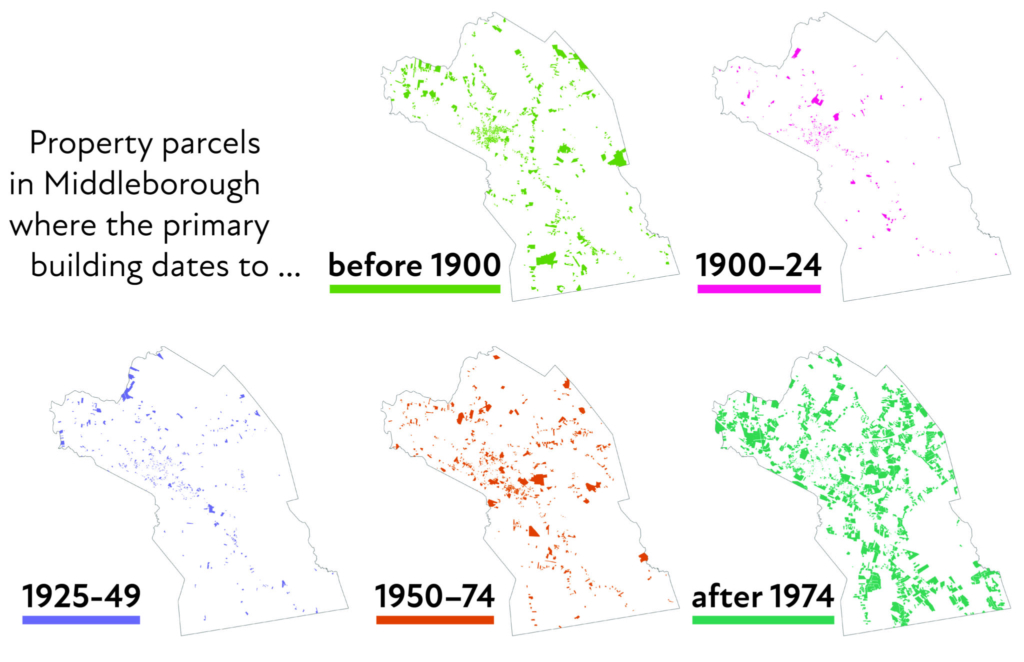

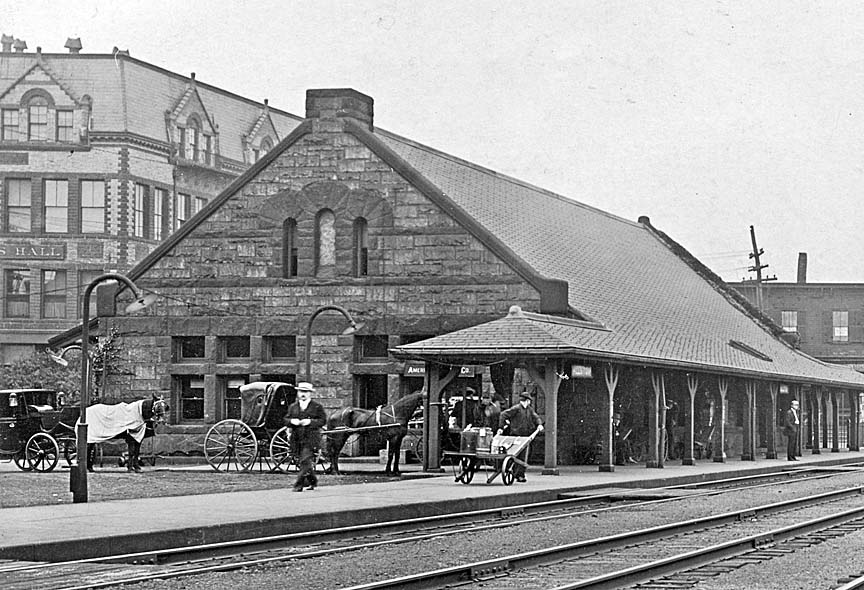

The following sets of maps show parcels of property in Middleborough colored by the estimated date of construction, taken from tax records, of the primary building on each parcel. As is obvious from the first map, what remains of Middleborough’s pre-1900 development pattern is a tightly nucleated town center, fringed by larger agricultural properties along the major roads running to neighboring communities.

In the early part of the 20th century, Middleborough retained the overall shape of this historic core. But by the 1950s and beyond, the town succumbed wholesale to suburban sprawl. The map of parcels with buildings erected from 1950–1974, and especially the map of post-1974 tracts, shows how Middleborough, like so many other suburban towns, gobbled itself up with land-hungry development patterns—an example of local control over land use which paid little respect to anything resembling a “historical” built landscape.

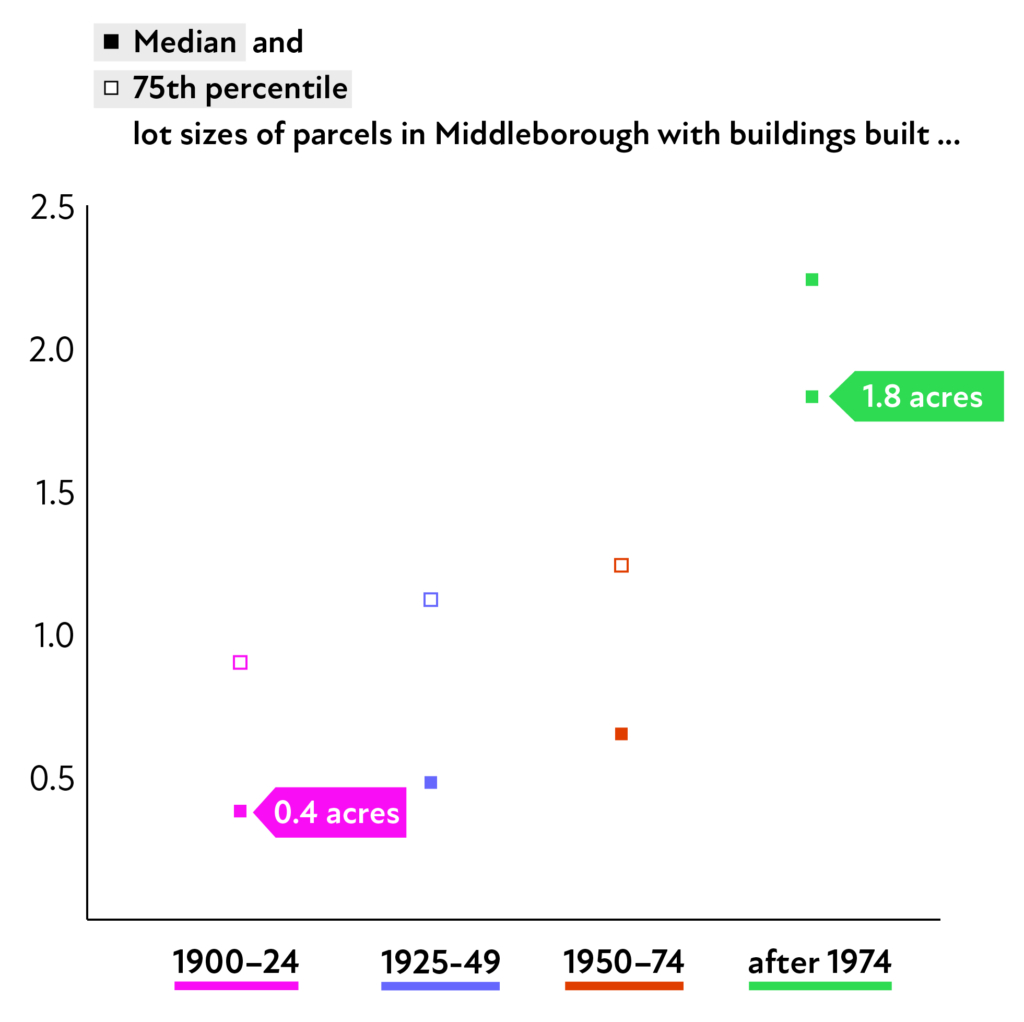

Statistics bear out this unfortunate story of local land-use controls failing to protect legacy landscapes. Of Middleborough’s parcels with buildings dating between 1900 and 1925, the vast majority are smaller than one acre, and the median parcel size is just under 0.4 acres. Over the 20th century, lot sizes grew and grew, to an average size of nearly 0.5 acres between 1925 and 1949, 0.7 acres between 1950 and 1974, and a staggering 1.8 acres for parcels with buildings built 1975 or later.

These are the very same decades during which towns in Massachusetts began to develop their own planning powers, and Middleborough’s story is hardly unique—nearly every municipality in Massachusetts went through the same transition in the postwar period.

If municipal planners in the 20th century had evinced even the slightest concern for historic preservation, the present-day landscape of Massachusetts would now look utterly different than it actually does. The overwhelming majority of today’s Massachusetts suburbanites live in homes and neighborhoods that would have been utterly out of character even as late as the 1930s. In fact, at the scale of the residential clusters where most people lived, nearly every place in Massachusetts—even rural and suburban communities—was far more dense 150 years ago today than today.

There is little evidence, then, that local control has ever done much to preserve the “historic character” of municipalities in Massachusetts. What, then, might local control actually be doing? The answer is hiding in plain sight in towns’ own 20th century planning documents. By the end of the 19th century, most municipalities outside of Boston’s inner core and a handful of industrial centers were sleepy agricultural towns, with few prospects for economic growth. Their fortunes changed thanks to two developments: the rise of the private automobile and the emergence of a home finance system which strongly favored the spatial segregation of investment into “desirable” neighborhoods.

Suddenly, around the middle of the 20th century, suburban municipalities realized that they had a tremendous economic asset that had only the thinnest connection to the conditions which had created their “historic character.” As the structural changes in the 20th century economy deepened, municipalities saw fields of gold in the form of single-family homes on larger and larger lots, served almost exclusively by automobile transportation and designed to enforce invisible barriers around class, race, and family composition. Town after town chose to embrace this type of development—a landscape pattern that was radically different from historic precedent—in order to chase the money and growth that it promised.

If there is a “historic character” that is well-protected and well-served by the jealously independent municipal control of land use, then, it is this one highly specific moment: the era that begin in the late 1940s, when primarily white, primarily middle-class homeowners drove a total transformation in suburban towns and nearly completely destroyed what existed up to that point of their earlier form and function. The people who rankle against “outsiders” upsetting the character of their town may point to a handful of preserved buildings or a beloved park as the features they are trying to save. But what they will in fact end up saving in reality is something very different, and something with only a dubious claim to “historic” value—a landscape that preserves and perpetuates the worst inequalities of the 20th century.

The spatial planning systems of many European countries offer an illustrative counter-example to the American misconception that local planning is the best tool for achieving historic preservation. Visit almost any small town center in, say, Sweden or Italy or Poland, and you’ll almost certainly find a landscape that better preserves the character of centuries past than any town in Massachusetts. And although these countries each have their own unique planning idiosyncrasies, all of them provide far more centralized control to regional and national political units. The United States is an outlier in terms of how much power local authorities have over land-use decisions—and also an outlier in terms of how many historic landscapes have been wiped out.

And the struggle between local and state authorities to adapt political and governance systems to changing conditions is itself deeply embedded in Massachusetts’ historic legacy. To take just one of many examples, consider what the state did two centuries ago out of frustration that municipalities were not taking the growing modern need for fire protection seriously. In Chapter 120 of the Massachusetts Acts of 1824, the Legislature provided a mechanism for fire engine companies to petition the county and state directly for appointment, in the case that a town’s “selectmen shall refuse or delay” to do so.

Like the towns that were slow to accept the need for fire protection in 1824, so too are today’s towns slow to accept the need for broad-scale land-use planning that accommodates growth while protecting historic landscapes in a coordinated fashion. The fact of the matter is that the population of Massachusetts will continue to rise, absent a world-historical catastrophe or neo-eugenic population reduction schemes.

This population growth, coupled with other changes in the state’s demographic profile, will inevitably require new housing. And under the current planning regime, controlled largely by local authorities, the vast majority of that new housing will go in places that really does degrade the historic character of Massachusetts: in sprawling single-family tracts and in larger development plopped down simply wherever land is cheapest and regulations are weakest. To steer development otherwise would require making decisions that might be locally unpopular, but which advance a broader view of historical and environmental preservation at the scale of the entire state.

Nobody anywhere in Massachusetts lives within a functional geography that resembles anything like the economic, social, and environmental systems of centuries past. People’s daily lives, in the routes and routines that take them from to home to work, to schools and to stores, are never captured within the bounds of a single municipality. Markets for labor and capital totally disregard the boundaries that separate one city or town from another. And yet for reasons that have mostly to do with historical inertia and the jealous protection of unequal privileges, land use controls remain tightly trapped within these now largely irrelevant geographies.

Unlike the most unrepentant pro-development activists, I really would like to see Massachusetts commit to a planning system that preserves the historic character of its cities and towns, and one which does in fact recognize that each place in the state has unique characteristics of its very own. But there is no less reliable method of doing so than simply allowing each municipality to do as it pleases, clinging to its own local prerogatives and incessantly rebuking even the most gentle efforts towards regional control.

If we want to protect what makes the landscape of Massachusetts cities and towns special, we must first of all protect them from themselves.

Garrett Dash Nelson is president and head curator at the Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png)