Lifestyle

What Makes a Good Red-Carpet Host?

Being a red-carpet host doesn’t sound so bad: just wear something spangly and chat with celebrities on their way into an awards show. Ask a few questions, ideally ones that let actors plug the brands that dressed them, and send them off to collect their trophies.

If only it were that easy.

On the red carpet before the Screen Actors Guild Awards on Sunday night, the YouTube star and former late-night host Lilly Singh dutifully performed the role for Netflix’s preshow. She asked Jane Fonda for advice for young actresses, and Pamela Anderson about craft services on her projects. She probed a baffled-looking Harrison Ford for “tea” about Ms. Fonda and Jason Segel.

Some armchair critics on social media were harsh, calling Ms. Singh’s interviews stilted and cringey, her approach overenthusiastic or underinformed. (Her co-host, the actress and comedian Sasheer Zamata, was mostly spared such criticism.)

These moments highlight just how challenging it is to be a good red-carpet host, a slippery role that demands fluency in dozens of films (and sometimes television shows, too), as well as an ability to generate instant chemistry with any actor who sweeps by. Those tapped for the job — a mix of comedians, actors, influencers and reality stars — must squeeze out 60-second, mildly elucidating interviews amid a throng of journalists, publicists and photographers. The exposure is great. The potential for gaffes is high.

It’s a role that has undergone serious transformation since the 1990s, when Joan Rivers, the first host of “Live From the Red Carpet” on E!, began to riff amusingly but savagely about the celebrity procession. She made brutal jabs about peoples’ bodies. She insulted Oprah, Lady Gaga and Rihanna. To hear her tell it, nearly everyone was a tacky disaster.

“Being publicly told that my dress is hideous will never feel quite as awesome,” the actress Anna Kendrick posted on social media after Ms. Rivers’s death in 2014. “You will be truly missed.”

In the post-Rivers era, some wanted to see red-carpet hosts take a different approach to the role. In 2015, a campaign called #AskHerMore from the Representation Project urged red-carpet interviewers including Ryan Seacrest and Giuliana Rancic to ask women in Hollywood questions that went beyond their choice of attire.

Laverne Cox, who became the red-carpet host of “Live From E!” in December 2021, updated Ms. Rivers’s typical “Who are you wearing tonight?” with a question she hoped would give interviewees more room for expression: “What story are you telling us with this look tonight?”

If she made the job look easy, it might have been because her preparation was so rigorous. In 2023, she told The New York Times about her process, which involved five-hour study sessions readying questions for every nominee who might walk by, and even the ones who probably would not. She reviewed the pronunciations of surnames and film titles. She aimed to start conversations about clothing, but also about the preparation and physicality that actors brought to their roles.

Ms. Cox approached the carpet as a “fan girl,” she said. “It’s been a different way for me, hopefully, to highlight people’s humanity. As an artist, we’re arbiters of empathy and humanity. And I think it’s possible as a red-carpet host to also do that.” (She announced last month that she was leaving the role.)

The current cadre of red-carpet hosts have each brought their own flavor to the job. Amelia Dimoldenberg, the host of the video series “Chicken Shop Date,” preferred to shamelessly flirt with attendees at the Golden Globes, where Andrew Garfield appeared no match for her charm. Keke Palmer’s effusive enthusiasm on the Met Gala carpet resulted in a viral mini theme song for the rapper Meghan Thee Stallion in 2021. Last March, Vanessa Hudgens said she had “a lot of fun” as a host for ABC’s Oscars preshow, which she has done for the last three years.

All have avoided major dust-ups, whereas other red-carpet interviewers have stumbled. This month, The Associated Press apologized to the singer and producer Babyface after one of its journalists shouted over him during an interview on the Grammys carpet. (She had been trying to grab the attention of another singer, Chappell Roan.) The model Ashley Graham muddled through a terse exchange with Hugh Grant when she was a host on the Oscars red carpet in 2023.

“What are you wearing tonight, then?” Ms. Graham asked the actor.

“Just my suit,” he responded.

She recovered and asked if he’d had fun filming the mystery “Glass Onion.”

“Uh, almost,” he said.

ABC has not yet announced who will host its red carpet before the Academy Awards on Sunday, though Ms. Dimoldenberg will return as a red-carpet correspondent.

She seems to be aware that her work is cut out for her: A representative for Ms. Dimoldenberg said she was not available for an interview on Monday, because she had writing to do.

Lifestyle

Internal memo details cosmetic changes and facility repairs to Kennedy Center

A person walks a dog in front of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 10, 2026.

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

An internal email obtained by NPR details some of the projected refurbishments planned for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. The renovations are more modest in scale and scope than what President Trump has publicly outlined for the revamped arts center, and it is unclear whether or not these plans are the extent of the intended renovations.

The email was sent on Feb. 2 by Brooks Boeke, the director of the Friends of the Kennedy Center volunteer program, to tour leaders and some staffers at the arts complex. In a response to NPR emailed Tuesday, Roma Daravi, the Kennedy Center’s vice president of public relations, wrote: “The Trump Kennedy Center has been completely transparent about the renovations needed to restore and revitalize the institution, ever since these proposals were unveiled for Congressional approval last summer. The changes that the Center will undergo as part of this intensive beautification and restoration project are critical to saving the building, enhancing the patron experience and transforming America’s cultural center into a world-class destination.”

The center’s closure was announced after many prominent artists canceled their planned appearances, saying that the Trump administration had politicized the arts. The Washington National Opera, which had been a resident organization at the Kennedy Center, left its home there last month, citing a “financially challenging relationship” under the center’s current leadership; The Washington Post, in an analysis of Kennedy Center ticket sales last October, reported that ticket sales had plummeted since Trump became the center’s chairman – even before the complex’s board renamed the venue as the Trump-Kennedy Center in December.

In her memo, Boeke cited Carissa Faroughi, the Kennedy Center’s director of the program management office. Boeke said that upcoming renovations to the complex’s Concert Hall will include replacing seating and installing marble armrests, which President Trump touted on his Truth Social platform in December as “unlike anything ever done or seen before!” Other changes include new carpeting, replacement of the wood flooring on the Concert Hall stage and “strategic painting.”

The planned changes to the Grand Foyer, Hall of States and Hall of Nations include a change of color scheme, from the current red carpeting and seating to “black with a gold pattern.” The carpeting and furnishings in these three areas and its electrical outlets were redone just two years ago, according to the Kennedy Center, and were accomplished without interrupting performances and programming.

Other planned work on the complex include upgrades of the HVAC, safety and electrical systems as well as improving parking. It is unclear whether these plans are the extent of the intended renovations; Daravi declined to answer that specific question.

The scope of the project as outlined in the memo differs sharply from public statements by President Trump, who said earlier this month on social media and in exchanges with the press that he intends a “complete rebuilding” and large-scale changes to the Kennedy Center, and that the arts complex is “dilapidated” and “dangerous” in its current state.

Earlier this month, Trump said that a two-year shutdown of the Kennedy Center is necessary to execute these renovations. This idea was echoed by the center’s president, Richard Grenell. Grenell wrote on X that the Kennedy Center “desperately needs this renovation and temporarily closing the Center just makes sense – it will enable us to better invest our resources, think bigger and make the historic renovations more comprehensive.”

On Feb. 1, Trump announced his plans to close the center entirely for two years “for Construction, Revitalization, and Complete Rebuilding” to create what he said “can be, without question, the finest Performing Arts Facility of its kind, anywhere in the World.” He later said that the project would cost around $200 million. The announcement came after many prominent artists had canceled their existing scheduled appearances at the Kennedy Center.

Lifestyle

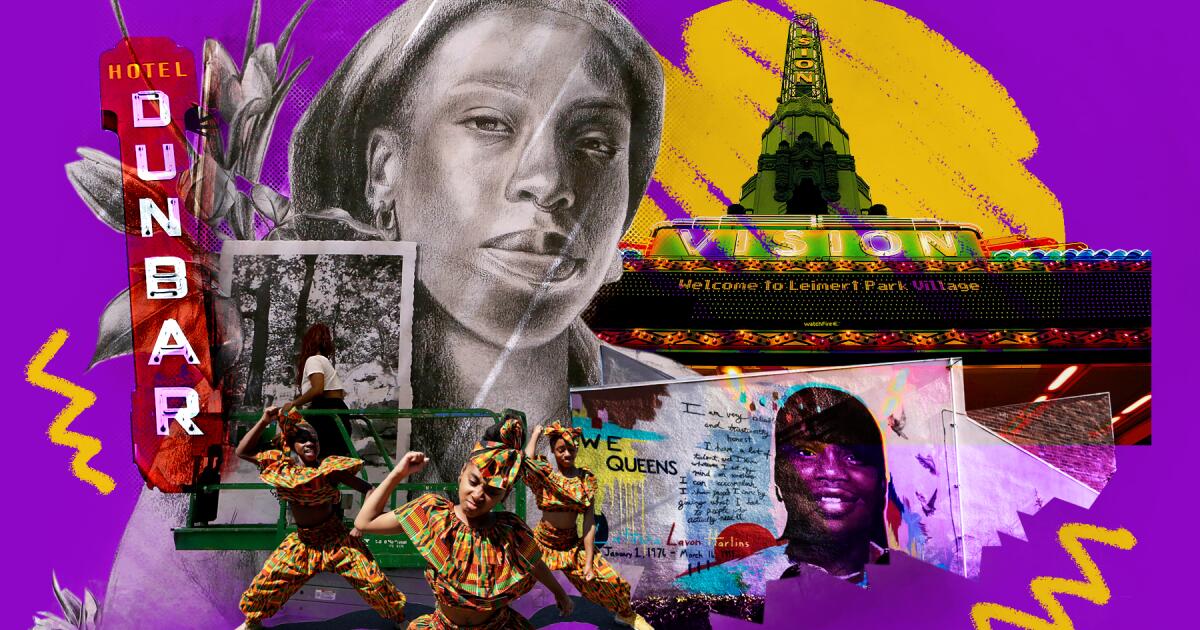

South L.A. just became a Black cultural district. So where should its monument stand?

For more than a century, South Los Angeles has been an anchor for Black art, activism and commerce — from the 1920s when Central Avenue was the epicenter of the West Coast jazz scene to recent years as artists and entrepreneurs reinvigorate the area with new developments such as Destination Crenshaw.

Now, the region’s legacy is receiving formal recognition as a Black cultural district, a landmark move that aims to preserve South L.A.’s rich history and stimulate economic growth. State Sen. Lola Smallwood-Cuevas (D-Los Angeles), who led the effort, helped secure $5.5 million in state funding to support the project, and in December the state agency California Arts Council voted unanimously to approve the designation. The district, formally known as the Historic South Los Angeles Black Cultural District, is now one of 24 state-designated cultural districts, which also includes the newly added Black Arts Movement and Business District in Oakland.

Prior to this vote, there were no state designations that recognized the Black community — a realization that made Smallwood-Cuevas jump into action.

“It was very frustrating for me to learn that Black culture was not included,” said Smallwood-Cuevas, who represents South L.A. Other cultural districts include L.A.’s Little Tokyo and San Diego’s Barrio Logan Cultural District, which is rooted in Chicano history. Given all of the economic and cultural contributions that South L.A. has made over the years through events like the Leimert Park and Central Avenue jazz festivals and beloved businesses like Dulan’s on Crenshaw and the Lula Washington Dance Theatre, Smallwood-Cuevas believed the community deserved to be recognized. She worked on this project alongside LA Commons, a nonprofit devoted to community-arts programs.

Beyond mere recognition, Smallwood-Cuevas said the designation serves as “an anti-displacement strategy,” especially as the demographics of South L.A. continue to change.

“Black people have experienced quite a level of erasure in South L.A.,” added Karen Mack, founder and executive director of LA Commons. “A lot of people can’t afford to live in areas that were once populated by us, so to really affirm our history, to affirm that we matter in the story of Los Angeles, I think is important.”

The Historic South L.A. Black Cultural District spans roughly 25 square miles, situated between Adams Boulevard to the north, Manchester Boulevard to the south, Central Avenue to the east and La Brea Avenue to the west.

Now that the designation has been approved, Smallwood-Cuevas and LA Commons have turned their attention to the monument — the physical landmark that will serve as the district’s entrance or focal point — trying to determine whether it should be a gateway, bridge, sculpture or something else.

And then there’s the bigger question: Where should it be placed? After meeting with organizations like the Black Planners of Los Angeles and community leaders, they’ve narrowed their search down to eight potential locations including Exposition Park, Central Avenue and Leimert Park, which received the most votes in a recent public poll that closed earlier this month.

As organizers work to finalize the location for the cultural district’s monument by this summer, we’ve broken down the potential sites and have highlighted their historical relevance. (Please note: Although some of the sites are described as specific intersections, such as Jefferson and Crenshaw boulevards, organizers think of them more as general areas.)

Lifestyle

Urban sketchers find the sublime in the city block

Portland’s Union Station, captured in watercolor and pen by an artist at the Urban Sketchers Portland event.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

Great landscape art can take you into a world: the majestic hills of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Southwestern sublime; the pastoral calm of Monet’s water lilies. But for years now, groups of amateurs have been gathering with sketchbooks in cities across the world to turn their artistic gaze to the everyday sights of skyscrapers and sidewalks — and find beauty there.

The idea of “urban sketchers,” or the name at least, started almost 20 years ago. Gabriel Campanario was looking to get to know his new home — and improve his drawing skills.

“We had just moved to Seattle, and I started drawing. Like every day I drew the commuters on the bus, I would draw the mountains, the buildings,” remembered Campanario.

He posted his drawings on the website Flickr and invited other artists to join the online group, which led to in-person groups. And then more chapters, and then international gatherings. Urban Sketchers now reports more than 500 chapters in over 70 countries.

“You can go to another town and meet up with a Sketchers group there,” said Campanario. “And you may not speak the language, but they all can look at your sketchbook and somewhat relate.”

Urban Sketchers Portland was one of the earliest chapters. They meet up monthly. Amy Stewart is one of the organizers.

“We’ll just pick a different neighborhood to explore, where we might be drawing old houses, or little corner markets, or maybe there’s a cool old movie theater to draw,” said Stewart.

Stewart is a writer by profession and says a lot of the sketchers who show up (usually about 50 or so) are similarly amateurs, along with a few more-experienced artists.

Karen Hansen, who discovered Urban Sketchers last year, came prepared with a folding chair and a magnetic watercolor paint palette, so she could pop in the colors she wanted to use for today’s painting.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

At a recent meetup at Portland’s Union Station, self-described recovering architect Bob Boileau appreciated that after a career spent drawing straight lines, “It’s nice to just get some squiggly in there and, and put some color and draw how I feel.”

Others, like sketcher Karen Hansen, noted that stopping and really paying attention to a scene helped her see the details that she had taken for granted in everyday life.

“When you’re drawing and painting something, you’re really looking at the shapes and the shadows and the textures,” said Hansen.

At the Portland meetup, sketchers were gathered in little clusters around the train station, capturing its red bricks and tall clock tower with watercolors, or pen and ink, or colored pencils.

It’s arguably not as majestic as most rural landscapes, but Noor Alkurd, drawing at his second Urban Sketchers meetup, said that the boxes and lines of cities are great for beginning artists. And besides, landscapes are overrated.

Urban Sketchers events end with a “throwdown,” where all the artists lay out their sketchbooks and share their work with each other.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

“I mean, come on — cityscapes are so fun!” Alkurd said with a laugh. “I think drawing has helped me just see more of everyday life. It kind of helps you train your own eye for what you find beautiful.”

At the end of the sketch session, all of the participants laid their finished art side by side to compare and admire.

There was some shop talk among sketchers about technique and materials, and some recognition of progress for sketchers who had been coming for a while. But mostly, sketchers said it’s just a chance to create a record of a moment, to take in other perspectives, and to notice a little bit more about the city they see every day.

-

Oklahoma2 days ago

Oklahoma2 days agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoA SoCal beetle that poses as an ant may have answered a key question about evolution

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoJames Van Der Beek shared colorectal cancer warning sign months before his death

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoHP ZBook Ultra G1a review: a business-class workstation that’s got game

-

![“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review] “Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]](https://i1.wp.com/www.thathashtagshow.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Redux-Redux-Review.png?w=400&resize=400,240&ssl=1)

![“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review] “Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]](https://i1.wp.com/www.thathashtagshow.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Redux-Redux-Review.png?w=80&resize=80,80&ssl=1) Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCulver City, a crime haven? Bondi’s jab falls flat with locals

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTim Walz demands federal government ‘pay for what they broke’ after Homan announces Minnesota drawdown

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week ago‘I Keep Myself Very Fit’: Rod Stewart’s Age-Defying Exercise Routine at 81