Entertainment

The country’s first paramedics were Black. James McDaniel wants to tell their story onscreen

“In each human endeavor there’s an individual of coloration smack dab in the course of it,” says actor James McDaniel. “I might go on perpetually speaking about folks of coloration we don’t learn about who’ve accomplished extraordinary issues.”

McDaniel, whose Hollywood historical past contains nearly a decade taking part in Lt. (later Capt.) Arthur Fancy on “NYPD Blue,” is speaking concerning the ardour he feels for his newest mission — growing a tv collection about Freedom Home Ambulance Service. Because the nation’s first cell emergency medical service, based in 1967, it was primarily staffed by African Individuals who grew to become the nation’s first paramedics.

Earlier than Freedom Home, there weren’t any ambulances as we all know them at the moment, says the group’s co-founder, Phil Hallen, 91. “There have been hearses — Cadillacs or Buicks — and also you had a cot within the again. You simply put folks again there.”

Again then cops additionally served as first responders and would ferry sick or injured folks to the hospital, Hallen says. However neither choice got here with staff who knew learn how to administer life-saving first support on the scene or en route, Hallen says. With out extra medical intervention, many sufferers died on their option to the hospital. Medical coaching for ambulance staff — together with the design of the ambulances, together with the sirens, the flashing lights and radios for speaking with medical doctors on the hospital — had been created by Freedom Home.

A mannequin ambulance designed by Dr. Peter Safar, circa 1967-1975.

(College Archives/College of Pittsburgh Library System.)

Freedom Home ought to be universally recognized, says McDaniel, because it laid the groundwork for the fashionable emergency medical system that has saved numerous lives worldwide within the six a long time since. However, he says, “I’m nearly 100% assured that when you went out into the road and stopped the primary EMS van you noticed, and also you talked about Freedom Home Ambulance Service, they wouldn’t have heard about it.”

McDaniel feels a selected urgency about altering that. He believes the story of Freedom Home is the proper narrative for this second in time — because the world is trying to heal and study from the racial justice uprisings that befell within the wake of George Floyd’s homicide in 2020.

“It is a story about triumph of an interracial group of human beings that held one another’s fingers, cherished one another and altered the world,” says McDaniel. “That is what we have to hear proper now. As a result of if we will’t remedy our racial issues, then God assist us.”

McDaniel and his workforce — together with co-creator and writing associate Derek Jennings — did intensive analysis to place collectively their pitch deck for the present. Coloration Farm Media, the self-described “Motown of movie, tv and tech,” is serving as a producing associate.

James McDaniel on the set of the NBC present, “The Night time Shift.”

(Gabe Sachs)

A major a part of McDaniel’s early analysis included interviewing individuals who labored with Freedom Home within the Nineteen Sixties and ‘70s, together with Hallen and EMT John Moon, who was the primary particular person to intubate a affected person outdoors of a hospital in addition to being among the many first EMTs to make use of Narcan to deal with heroin overdoses and to transmit EKGs from the sector again to the emergency room.

“Every thing about emergency medical service at the moment originated with Freedom Home,” says Moon. “I believe the fantastic thing about working there may be that we had been in a position to overcome the assorted boundaries and distractions that had been thrown at us to ship a system that’s glorified on this nation. We didn’t let our life struggles influence what we had been doing on the time.”

The struggles of the Black group in Pittsburgh within the Nineteen Sixties contributed, largely, to Freedom Home’s creation, says Anita Srikameswaran, a former medical reporter for the Pittsburgh Publish-Gazette who wrote extensively about Peter Safar, an Austrian-born anesthesiologist who is taken into account the “father of CPR.” Safar labored because the chair of anesthesiology at College of Pittsburgh College of Drugs when he collaborated with Hallen to discovered Freedom Home.

“Within the Black group, there was a insecurity {that a} cop would come and take you, and in the event that they did, you couldn’t be sure they might offer you a good shake and deal with you proper,” says Srikameswaran.

Dr. Peter Safar trains three unidentified Freedom Home EMTs in learn how to use a respiratory masks.

(College Archives/College of Pittsburgh Library System.)

Safar had been advocating, with out a lot luck, to offer medical coaching to ambulance staff when Hallen approached him with the concept of beginning a non-public ambulance service in Pittsburgh’s Hill District — a predominantly African American space composed of assorted low-income, inner-city neighborhoods.

Hallen was the president of the Maurice Falk Medical Fund, which was tasked with grant-making in service of minority communities and civil rights, he recollects. Hallen had pushed an ambulance (which was actually a hearse) when he was learning in Syracuse, and he knew the Hill District had specific issues securing emergency medical assist. The ensuing mortality fee, he says, was shockingly excessive.

Safar and Hallen started recruiting unemployed Black males from the Hill to obtain medical coaching with the intention to implement Safar’s concepts for pre-hospital emergency care whereas offering very important — and high-quality — ambulance service to space residents.

A Freedom Home Ambulance EMT caring for a affected person, doubtless throughout a coaching train, circa 1971-75.

(College Archives/College of Pittsburgh Library System)

Twenty Black trainees comprised the primary class of Freedom Home paramedics. After their first spherical of medical research, they started 9 months of in-the-field coaching. In its first yr, in line with a profile of Safar posted on-line by the College of Pittsburgh, Freedom Home Ambulance Service made 5,868 runs and transported 4,627 sufferers, responding to a median of 15 calls a day.

“We had been labeled as hardcore unemployables, the least more likely to succeed. We had been known as society’s throwaways,” recollects Moon of the Freedom Home recruits. “The one factor society tousled on once they labeled us these issues is, they by no means advised us.”

With the care and a spotlight of the nation’s first EMTs, Freedom Home grew to become an enormous success, says Hallen.

“We realized it was groundbreaking as a result of — by way of medical journals and a community of healthcare media — folks had been starting to take discover,” says Hallen. “Safar was growing these breakthrough concepts, and Freedom Home was implementing them. The articles popping out made us notice what was occurring was of nationwide and worldwide significance.”

Moon blames racism for Freedom Home’s downfall. In 1975 the service shut down after town of Pittsburgh launched its personal ambulance service — based mostly on Freedom Home’s singular achievements. The town didn’t renew the Freedom Home contract and absorbed its property.

“Nicely-to-do folks in Pittsburgh had not obtained the high-level pre-hospital care that the Hill District had, and so they complained about it, they began calling their representatives and saying it’s important to do one thing about this.” says Moon. “Freedom Home was unable to compete in that political setting.”

The town pledged to rent on the Freedom Home paramedics, says Moon, however that proved to be lip service.

“They needed to remove any point out of Freedom Home, so town discovered a systemic approach of hunting down as many Freedom Home workers as they might,” says Moon, including that Black EMTs had been uncared for, relegated to bystanders at accident scenes and topic to fixed and radical shift modifications. “Issues that examined your resilience, and only a few Freedom Home workers had been in a position to endure this remedy.”

Moon persevered, although, and finally rose by way of the ranks to turn out to be chief supervisor of Pittsburgh EMS. He carried out the primary variety recruitment program within the metropolis. One other Freedom Home paramedic, Mitchell Brown, went on to turn out to be the director of the division of public security for Columbus, Ohio.

McDaniel says it’s each troubling and comforting to search out out about tales like these of Freedom Home, later in life.

“You’re not going to study this at school. When my youngsters had been rising up, it’s Black Historical past Month, and everyone’s speaking about MLK, and yearly it’s the identical syllabus,” he says, including that he made it his quest to find untold Black tales, increase a formidable library within the course of. “Freedom Home is, fairly actually, one in all many.”

Bringing the Freedom Home story to the display, he hopes, will give the operation the visibility it deserves.

“I’m only a passionate man at this level in my life who desires to inform tales that matter about my folks,” he says.

Movie Reviews

'Killer Heat' movie review: A mystic mystery

Philippe Lacôte’s Killer Heat is a suspense thriller set on the tranquil island of Crete, Greece. The island’s stunning landscape, with rugged mountains and pristine beaches, creates the perfect setting for this atmospheric mystery. Initially, the film may feel too laid-back for its own good, but as the plot unfolds, it finds its groove, delivering a cohesive, engaging story. Much like its setting, Killer Heat is refreshingly straightforward, avoiding a forced sense of suspense. The mystery unravels at a measured pace, allowing the viewer to savour the journey.

The plot itself may not break new ground, with relatively low stakes, but what makes it work is the absence of unnecessary storytelling shortcuts. Joseph Gordon-Levitt plays Nick Bali, a private investigator hired to look into the mysterious death of Leo (Richard Madden), the heir of the wealthy Verdakis family.

The film opens with Leo climbing a cliff while Bali narrates the Greek myth of Icarus, the man who flew too close to the sun. Leo soon falls to his death, and the family—except for Leo’s sister-in-law, Penelope (Shailene Woodley)—considers it a tragic accident.

Penelope, however, is convinced otherwise, refusing to trust the local police, claiming her “family owns them”, and that “in Crete, no one goes against the gods”. The film’s integration of Greek metaphors adds a touch of mysticism.

What’s refreshing about Killer Heat is that it doesn’t trick the audience. From the first scene, it’s clear that the culprit isn’t an outsider, but that doesn’t take away from the suspense.

Entertainment

Kim Kardashian wants the Menendez brothers to be freed as D.A. reviews case

Kim Kardashian wants Lyle and Erik Menendez, the brothers convicted in the grisly 1989 murders of their parents, to be freed.

The reality star, daughter of late O.J. Simpson attorney Robert Kardashian, has fashioned herself as an advocate for criminal justice reform. And, in a personal essay for NBC News, she wrote Thursday that she hopes that the brothers, who have already served 35 years in prison, could have their life sentences “reconsidered.”

“We are all products of our experiences. They shape who we were, who we are, and who we will be. Physiologically and psychologically, time changes us, and I doubt anyone would claim to be the same person they were at 18. I know I’m not!,” the Skims co-founder wrote.

Kardashian rehashed widely known facts in the case — that the brothers, then ages 21 and 18, shot and killed their parents, Jose and Kitty Menendez, in their Beverly Hills home — as well as their high-profile 1996 trials. But, she said, “this story is much more complex than it appears on the surface.”

“Both brothers said they had been sexually, physically and emotionally abused for years by their parents. According to Lyle, the abuse started when he was just 6 years old, and Erik said he was raped by his father for more than a decade. Following years of abuse and a real fear for their lives, Erik and Lyle chose what they thought at the time was their only way out — an unimaginable way to escape their living nightmare,” she said.

Erik Menendez, left, and is brother Lyle, in front of their Beverly Hills home.

(Ronald Soble / Los Angeles Times)

Listing issues with the trials and other legal missteps, Kardashian argued that “the media turned the brothers into monsters and sensationalized eye candy” and that they “had no chance of a fair trial against this backdrop.”

The beauty mogul has visited the brothers in prison and vouched for their “exemplary disciplinary records,” adding that a warden there told her that “he would feel comfortable having them as neighbors.” She asserted that life in prison is not the right punishment for them and argued that the exclusion of abuse evidence from their second trial denied them a fair go.

“The killings are not excusable. I want to make that clear. Nor is their behavior before, during or after the crime. But we should not deny who they are today in their 50s,” she wrote. “The trial and punishment these brothers received were more befitting a serial killer than two individuals who endured years of sexual abuse by the very people they loved and trusted.”

On Thursday, Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón said his office would review what he described as new evidence that the brothers were molested — a move that could lead to revised sentences.

While there was no question the brothers committed the murders, Gascón said, the issue is whether the jury heard evidence that their father molested them. Evidence detailing sexual abuse was presented during the brothers’ first trial, which ended in hung juries, but was largely withheld during their second trial, where they were convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Lyle Menendez, left, and Erik during a court appearance in Beverly Hills on April 2, 1991.

(Kevork Djansenzian / Associated Press)

Meanwhile, a series of creative projects over the past year have contributed to renewed interest in the brothers’ case and their highly scrutinized trials. Ryan Murphy’s splashy “Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story,” for example, raised questions, much like his past anthology series revived the discourse around the O.J. Simpson trial and the impeachment of former President Clinton. The Menendez brothers were also the focus of the Fox Nation documentary series “Menendez Brothers: Victims or Villains,” which premiered in March, as well as the Peacock docuseries “Menendez + Menudo: Boys Betrayed,” which presented new evidence and included an accusation of rape against patriarch Jose Menendez.

Citing evidence related to molestation claims, attorneys for the brothers filed petitions last year to reopen the case, and family members have rallied to get the men released. Others, like Kardashian, have argued that times have changed, and that the brothers’ allegations of abuse might have been received differently at trial today.

Times staff writers Salvador Hernandez, Hannah Fry and Richard Winton contributed to this report.

Movie Reviews

Union movie review & film summary (2024) | Roger Ebert

When Amazon workers on Staten Island successfully voted to unionize in the spring of 2022, becoming the corporate retailer’s first American workplace to do so, it was hailed as one of the most important labor victories in the United States in nearly 100 years.

For the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) to organize employees at the JFK8 warehouse to vote in favor of union representation was a David versus Goliath story for the age of globalization — and a rousing reminder that collective grassroots efforts can still succeed despite massive employer concentration, management intimidation, and other hindrances to building worker power. And that an independent, worker-led coalition led the drive at this 8,000-plus-employee facility, rather than an established union, made its victory all the more impressive, even as the vote to unionize brought organizers into uncharted territory and set up a protracted legal battle with Amazon, which has since refused to recognize the ALU or negotiate a contract.

Telling the story of how the ALU reached this historic moment, “Union,” a new documentary co-directed by Brett Story (“The Hottest August”) and Stephen Maing (“Crime + Punishment”), takes a detail-driven, ground-level approach, following current and former Amazon employees in Staten Island as they mount a grassroots worker-to-worker campaign, standing their ground against one of the world’s powerful corporations all the while.

No talking-head documentary but a keenly observational chronicle of the unionization push and its aftermath, “Union” often plays like a thriller by virtue of its sharp, smart editing rhythms. Early on, Story and Maing juxtapose Jeff Bezos blasting off into space on a rocket made by his Blue Origin company and Amazon workers trudging wearily into work; it captures the unimaginable scale of the company’s operations while foregrounding the human scale often concealed by breathless (yet inevitably compromised) reporting of Amazon’s designs on empire.

Made over the course of three years, Story and Maing’s film explores the human cost of the convenience economy and illuminates oppressive working conditions in Amazon’s factories. From constant surveillance to high injury rates and a lack of breaks, the pressures of working in Amazon warehouses compound to create punishing environments for workers, ones Amazon has steadfastly refused to address or even accurately report. And the threat of retaliation against workers who organize is ever-present; in addition to pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into union-busting campaigns that include mandatory “captive audience” meetings (which have since been banned in the state of New York), Amazon issues warnings of possible termination to workers involved with the unionization drive.

Bookended by footage of vast cargo ships transporting goods, a reminder of the slow, perpetual motion with which the gears of modern capitalism grind on, Story and Maing’s film is smart in how systematically its narrative lays out obstacles to the union’s success. It also insightfully depicts ground-level dialogue between workers as a powerful tool with which to overcome them. Some of the most remarkable footage, inside Amazon headquarters, covertly films one of those captive audience meetings; here, the company’s anti-union propaganda (One reads: “We’re asking you to do three simple things: get the facts, ask questions and vote no to the union”) is disrupted by ALU organizers, who successfully push back on Amazon managers just long enough to make their case to workers.

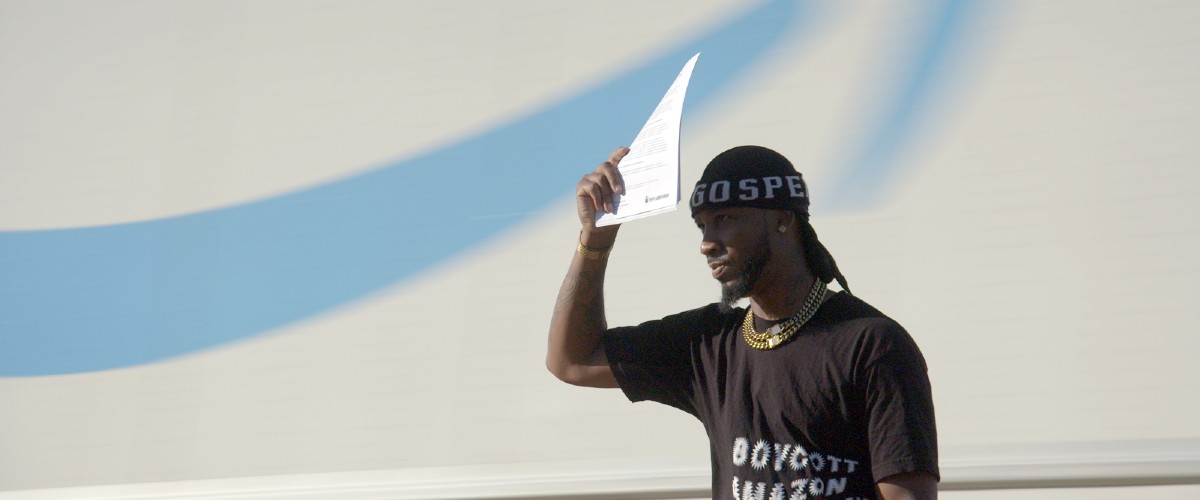

One of the ALU organizers, Chris Smalls, takes center stage in “Union,” though the documentary largely sidesteps the temptation to cast him as a conquering hero. (That’d be an easy trap, given that he became the organization’s public face across the period “Union” depicts.) Smalls, fired from Amazon after protesting inadequate PPE provision during the pandemic (and besmirched by the company’s general counsel as “not smart or articulate” in an internal meeting of executive leaders), is a father of three who was moved to activism by the flagrant injustice of the company’s abusive labor practices. As a leader, he’s at once charismatic and hard-charging, dedicated to his fellow “comrades” but ever driven to push forward even in the face of inter-union dissent.

One of the film’s great strengths is its ability to surface the multiplicity of tensions between organizers working toward a shared cause. Take the world of difference separating the experiences of two subjects: Maddie, a white college graduate using her campus activism experience to help the cause, and Natalie, an older Latina woman living out of her car for years. In one charged exchange, Natalie pushes back on the suggestion, made by white male organizers, that Chris intentionally gets himself arrested by New York police officers to draw attention to the unionization drive. Ultimately, Natalie’s dissatisfaction with the ALU—due to her disagreements with leadership as much as her desire to wait for larger union support—leads her to leave the organization. It’s a testament to the complexity of individual motivations and the absence of easy triumph in this type of effort.

“Union” documents the internal debates and disagreements over governance, organizing, and leadership strategies that divided the ALU before its successful unionization vote and were compounded by its subsequent failed attempt to unionize a second warehouse. Though Smalls’ force of personality, passion, and determination fueled the fight to unionize JFK8, the film carefully depicts this as a collective victory. It rarely gives in to the temptation to single out Smalls for praise at the expense of others, and making it clear that his leadership style also contributed to internal rifts in the ALU that at various points may have weakened its ability to further the union’s mission.

This becomes particularly important in the film’s latter half, after the unionization vote, at which point the sobering realities of the long work ahead come more fully into view. The heroism of the ALU organizers will never be in question. But with only one battle won in the war for workers’ rights, and Amazon continuing to contest or undercut its results by every means available, “Union” concludes on a note of weary fortitude rather than declarative victory. The film captures both the pain and the power of people at the base of a global infrastructure. By not departing from the frontlines of the fight against Amazon’s labor exploitation, Story and Maing bring the true face of their struggle into focus.

“Union” will be self-distributed theatrically, starting on Oct. 18. This review was filed from the film’s New York premiere at the New York Film Festival.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25439572/VRG_TEC_Textless.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25439572/VRG_TEC_Textless.jpg) Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoCharter will offer Peacock for free with some cable subscriptions next year

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoUkrainian stronghold Vuhledar falls to Russian offensive after two years of bombardment

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoWikiLeaks’ Julian Assange says he pleaded ‘guilty to journalism’ in order to be freed

-

Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoBeware of fraudsters posing as government officials trying to steal your cash

-

Virginia4 days ago

Virginia4 days agoStatus for Daniels and Green still uncertain for this week against Virginia Tech; Reuben done for season

-

Sports1 day ago

Sports1 day agoFreddie Freeman says his ankle sprain is worst injury he's ever tried to play through

-

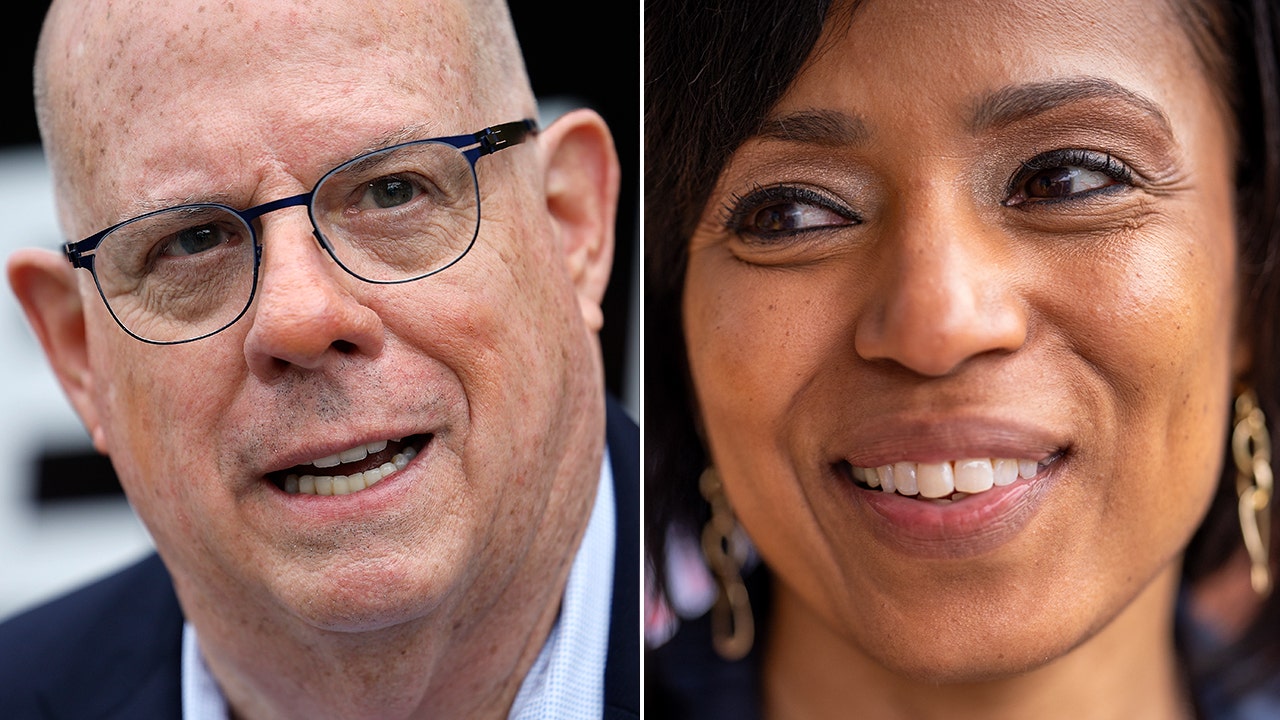

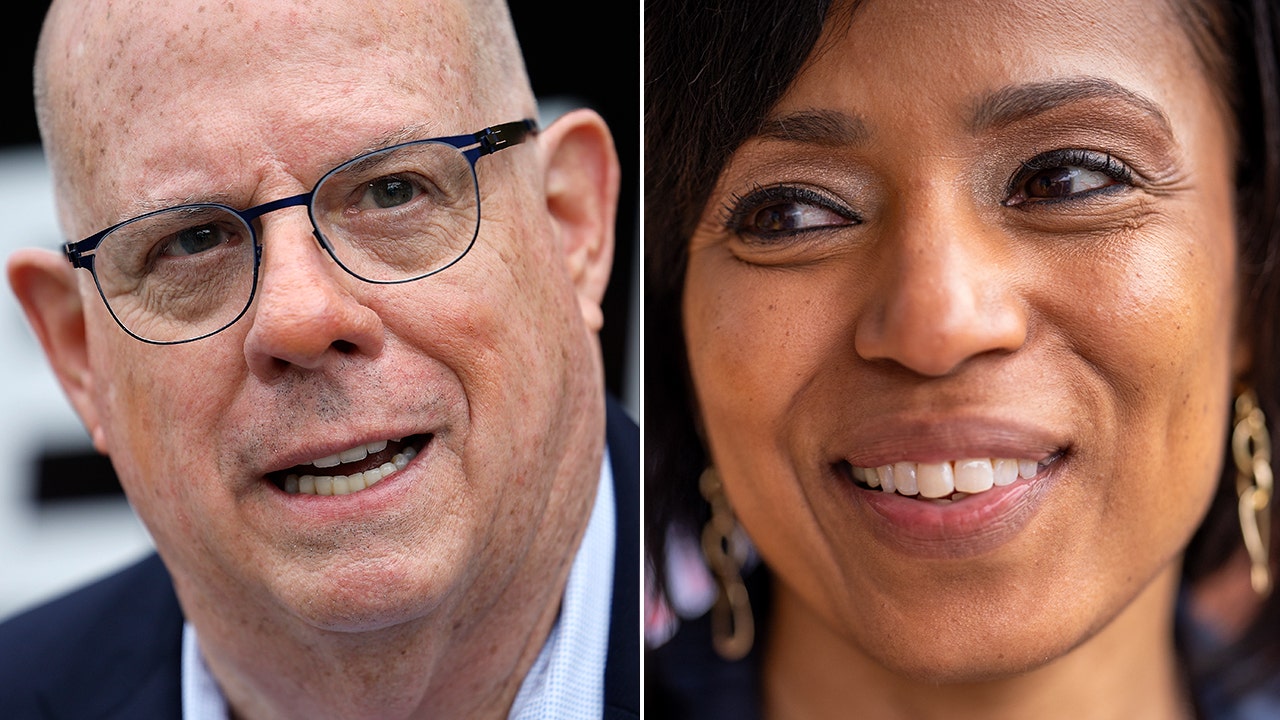

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoMaryland Senate race: Democrat Alsobrooks leads Republican Hogan in closely watched contest

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoVideo: Chemical Plant in Georgia Emits Thick Cloud of Smoke

)