Entertainment

Review: Feminist artists cast a skeptical eye at the linking of gender and nature in new L.A. show

“Life on Earth: Art & Ecofeminism” is a somewhat difficult exhibition to grab hold of, but that’s mostly because its important subject is so much larger than a diverse but relatively modest presentation can encompass.

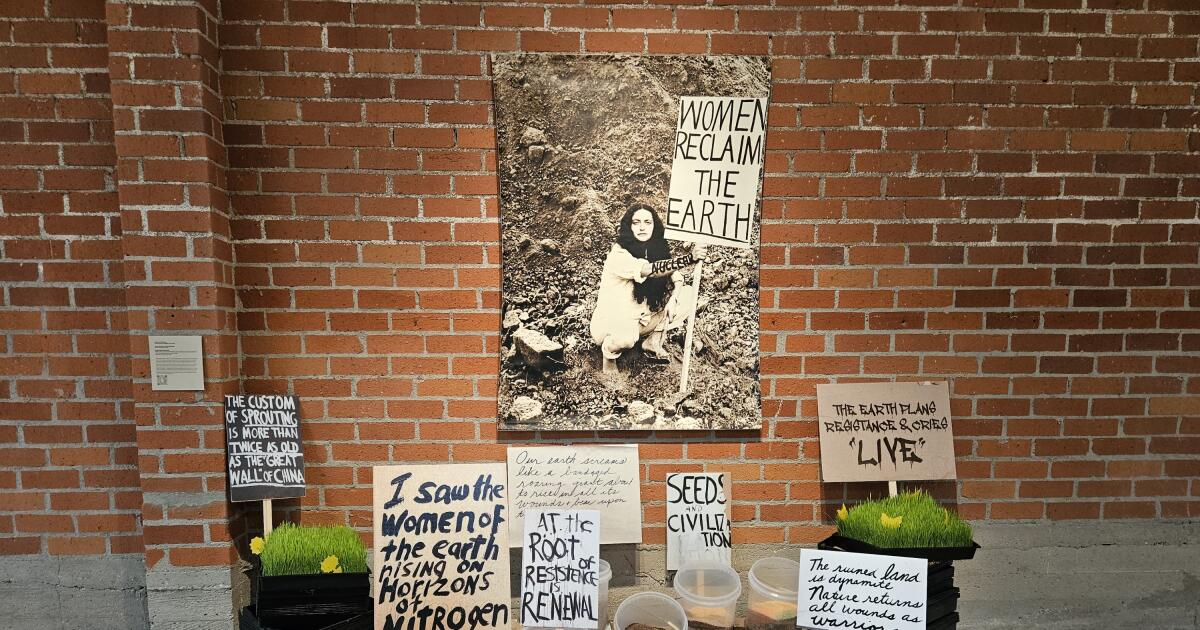

Ecofeminism rejects the idea of human dominance over nature. The inaugural show at the Brick, an independent art space formerly known as LAXArt and recently relocated to Western Avenue, features 18 works by international artists and collectives that touch several intriguing bases of ecofeminist art launched since the 1970s.

Insistence on the supremacy of people over the natural world is cited as the primary source of environmental destruction. Furthermore, the practice is tightly bound to the seemingly intransigent social marginalization of women. Remember Mother Nature? If we insist on regarding the natural world in such feminine terms, then authority over women is an essential — and equally destructive — corollary to authority over nature.

The show’s earliest piece might be an analogy for the whole. In 1972, when Aviva Rahmani was a student at the California Institute of the Arts, she directed and documented in slides a performance titled “Physical Education.” Filling a plastic bag with tap water, she and a performer drove 50-plus miles from the suburban school in parched Santa Clarita to the Pacific Ocean, stopping four times along the way to deposit teaspoons of water on the side of the road, then replacing each with a spoonful of dirt.

While a student at CalArts in 1972, Aviva Rahmani documented wasteful water practices in Southern California.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angles Times)

When Rahmani got to the beach, the muddy bag was emptied out in the sand and refilled with sea water. She promptly drove it back to CalArts, reversing the process. Upon arrival, she flushed the dirty water down a toilet.

In the exhibition, a cycle of elemental return and fundamental waste unfolds in slides projected from an automated tray onto an ordinary freestanding screen. The setup, common for pre-digital Conceptual art, is much like the way folks used to show the neighbors happy pictures of their summer vacation. Here, water transport assumes a form that is grandly ritualistic if decidedly prosaic.

None of the individual photographic images in “Physical Education” is especially distinctive. The artful feature of the work is instead embedded in the installation’s composition.

Rahmani’s pictures don’t come close to filling the screen, although they could easily have been projected that way like snaps from the family trip to Disneyland or Yosemite. Rather, they nestle down in a corner, modestly flashing by, one after the next, as the slide tray clicks in nonstop rotation. The mostly empty screen’s larger blankness implies that there’s plenty of room for many more pictures awaiting exposure. This work of ecologically minded art is positioned as just one self-aware fragment of a much bigger worldview that needs to be seen as holistic and systemic.

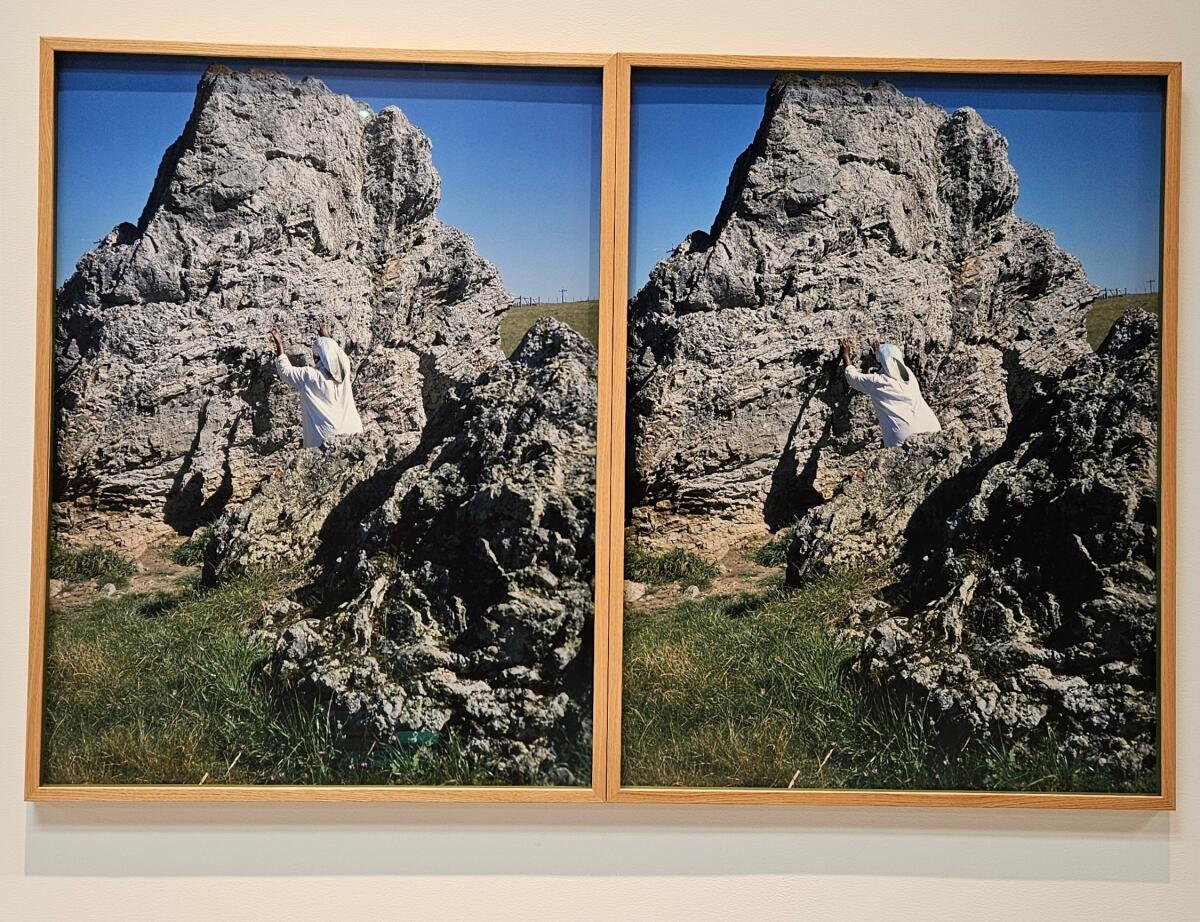

Nearby, a pair of large, documentary performance photographs made five decades later by L.A.-based yétúndé olagbaju resonates against Rahmani’s historical piece. At left in “protolith: heat, pressure,” the artist is seen from behind, dressed in a white robe and headscarf. They emerge from within a rocky outcropping in an otherwise grassy field and hold up their hands, as if in benediction. On the right, the composition is roughly the same, although now their hands press against the massive stone.

Off in the distance, a fence is glimpsed, suggesting a cultivated landscape rather than a wild one, while a lone telephone pole identifies the rural location as tethered to community via modern communication. The photographs smartly picture the classic irresistible force paradox. What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object? Can an artist alter a deeply established cultural relationship to the natural world?

Come to think of it, in these photographs, which is the force, and which is the object — the person or the rock? Or are they interchangeable?

L.A.-based artist yétúndé olagbaju performed a ritual laying on of hands on a rural stone outcropping.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

It takes a moment, but olagbaju’s gesture of first blessing, then touching a seemingly immovable boulder shifts your perspective, and that might be enough to generate at least incremental change. Like the steady drip-drip-drip of water on stone, which over millenniums reduces a monolith to sand, human contact will have its way.

The exhibition is not a comprehensive history of ecofeminist art. Pioneers of the genre such as Agnes Denes, who once transformed a Manhattan landfill into a wondrous urban wheat field, and Helène Aylon, who commemorated the end of the Cold War with anti-nuclear performance art, are absent. The Brick presentation is instead a provocative sketch suggesting that a museum would do well to undertake a full historical overview of ecofeminist art from the last half a century.

It’s also disappointing that no catalog accompanies the show; one is said to be in the works, but publication is not expected until next year, presumably so that new commissions, installations and mixed-media works can be documented and included. Art spaces used to deal with such complications by publishing a two-volume set — a primary one to accompany the exhibition as it opens and a small supplement to record additions. But that traditional practice seems to have fallen by the wayside.

It’s a loss. Yes, the two-tome process is more expensive to produce. Yet, for the benefit of the art audience, it should simply be regarded as necessary.

Still, smartly organized by Brick curator Catherine Taft, with curatorial assistants Hannah Burstein and Kameron McDowell, “Life on Earth” manages to cover a good deal of territory. In this contribution to the Getty-sponsored festival “PST Art: Art & Science Collide,” the breadth, both aesthetic and geographic, is wide.

A graceful mermaid swimming around in an industrial-strength water treatment plant in Lithuanian artist Emilija Škarnulytė’s film “Riparia” becomes a perilous siren, luring the unsuspecting to the rocks. Leslie Labowitz Starus, who has operated an urban farm in Venice for decades, puts sprouts on poetic display. Carolina Caycedo carves a trio of enormous seeds — squash, beans, corn — from wood as elegant sculptural abstractions. Projected videos of rushing rivers and roiling seas mix effortlessly with disparate photographs of human gender fluidity, which marks the people in A.L. Steiner’s exuberant collage environment papering gallery walls.

Fluidity describes gender and nature in A.L. Steiner’s installation of photographs and video.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Steiner’s installation helps unravel perhaps the oldest, most powerful source of the problematic fusion of nature and womanhood in ordinary cultural conceptions. The Book of Genesis doubled down not long after tagging biblical Eve as the agent of the fall from grace in the Garden of Eden. “Be fruitful and multiply,” the command then came, “and replenish the Earth, and subdue it.”

And subdue it. Subjugate women, subjugate nature. Think about that awful binary as the climate continues to change, while stormwater rises and fires burn.

‘Life on Earth: Art & Ecofeminism’

Where: The Brick, 518 N. Western Ave., L.A.

When: Tuesdays to Saturdays, through Dec. 21

Info: (323) 848-4140, www.the-brick.org

Movie Reviews

“Resurrection” Movie Review: To Burn, Anyway

“What can one person do but two people can’t?”

“Dream.”

I knew the 2025 film “Resurrection” (狂野时代) would be elusive the second I walked out of Amherst Cinema and into the cold air, boots gliding over tanghulu-textured ice. The snow had stopped falling, but I wished it hadn’t so that I could bury myself in my thoughts a little longer. But the wind hit my uncovered face, the oxygen slipped from my lungs, and I realized that I had stopped dreaming.

“Resurrection” is a love letter to the evolution of cinematography, the ephemerality of storytelling, and the raw incoherence of life. Structured like an anthology film and set in a futuristic dreamscape, humanity achieves immortality on one condition: They can’t dream. We follow the last moments before the death of one rebel dreamer, called the “Deliriant” or “迷魂者,” as he travels through four different dream worlds, spanning a century in his mind.

Being Bi Gan’s third film after the 2015 “Kaili Blues” (路边野餐) and the 2018 “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” (地球最后的夜晚), “Resurrection” follows Gan’s directorial style of creating fantastical, atmospheric worlds. Jackson Yee, known for being a member of the boy group TFBoys, stars as the Deliriant and takes on a different identity in each dream, ranging from a conflicted father-figure conman to an untethered young man looking for love to a hunted vessel with a beautiful voice. His acting morphs unhesitatingly into each role, tailored to the genre of each dream. Of which, “Resurrection” leans into, with practice and precision.

Opening with a silent film that mimics those of German expressionist cinema, “Resurrection” takes the opportunity to explore the genres of film noir, Buddhist fable, neorealism, and underworld romance. The Deliriant’s dreams are situated in the years 1900 to 2000, as we follow the evolution of a century of competing cinematic visions. The characters don’t utter a single word of dialogue in the first twenty minutes, as all exposition occurs through paper-like text cards that yellow at the edges. I was worried it would be like this for the whole film, but I stayed in the theater that Tuesday night, the week before midterms, waiting for the first line of spoken dialogue to hit like the first sip of water after a day of fasting.

Through a massive runtime that spans two hours and 39 minutes, this movie makes you earn everything you get. Gan trains the audience’s patience with a firm hold on precision over the dials of the five senses and the mind.

The dreams may move forward in time through the cultures of the twentieth century, but on a smaller temporal scale, the main setting of each dream functions to tell the story of a day in reverse. The first dream, being a film noir, is told on a rainy night. Without giving any more spoilers, the three subsequent dreams take place at twilight, during multiple sunny afternoons, and then at sunrise. “Resurrection” does not grant sunlight so easily; we are given momentary solace after being deprived of direct sunlight for a solid 70 minutes, until it is stripped from us again and we are dropped into the darkness of pre-dawn – not that I am complaining. I love a movie that knows what it wants the audience to feel. I felt a deep-seated ache as I watched the film, scooting closer to the edge of my seat.

“Resurrection” is a movie that is best watched in theaters, but a home speaker system or padded headphones in a dark room can also suffice. Some of its most gripping moments are controlled by sound. Loud, cluttered echoes of the world, whether from people chatting in a parlor or anxiety in a character’s head, are abruptly cut off with ringing silence and a suspended close-up shot. We are forced to reckon with what the character has just done. I knew I was a world away, but I was convinced and terrified at my own culpability and agency. If I were him, would I have done the same? I could only hear my thoughts fade away as we moved onto the next dream.

Beyond sight and sound, the plot also deals intimately with the senses of taste, smell, and touch, but you will have to watch the movie yourself to find that out.

My high school acting teacher once told us that whenever a character tells a story in a play, they are actually referencing the play’s overall narrative. This exact technique of using framed narratives as vessels of information foreshadowing drives coherence in a seemingly ambiguous, metaphorical anthology film. Instead of easy-to-follow tales that mimic the hero’s journey, we are taken through unadulterated, expansive explorations of characters and their aspirations. We never find out all the details of what or why something happens, as the Deliriant moves quickly through ephemeral lifetimes in each dream, literally dying to move onto the next, but we find closure nonetheless through the parallels between elements and the poetry of it all.

That is why I like to think of “Resurrection” as pure art. It is not bound by structure; it osmoses beyond borders. It is creation in the highest form; it is a movie that I will never be able to watch again.

Perhaps because the dream worlds are so intimate and gorgeous, the exposition for the actual futuristic society feels weak in comparison. We learn that there is a woman whose job is to hunt down Deliriants, but we don’t see the rest of the dystopian infrastructure that runs this system. However, I can understand this as a thematic choice to prioritize dreams over reality. Form follows function, and these omissions of detail compel us to forget the outside world.

What it means to “dream” is up for interpretation, and we never learn the specifics of why or how immortality is achieved. Instead, “Resurrection” compares dreaming to fire. We humans are like candles, the movie claims, with wax that could stand forever if never used. But what is the point in being candles if we are never lit?

The greatest reminder of “Resurrection” is our own mortality. Whether we run from the snow-dipped mountaintops to the back alleyways of rain-streaked Chongqing, we can never escape our own consequences. “Resurrection” gives me a great fear of death, but so does it reignite my conviction to live a life of mistakes and keep dreaming anyway.

Dreaming is nothing without death. Immortality is nothing without love. So, I stumbled back to my dorm that Tuesday night, the week before midterms, thinking about what I loved and feared losing. So few films can channel life and let it go with a gentle hand. I only watch movies to fall in love. I am in love, I am in love. I am so afraid.

Entertainment

Spotify once had a reputation for underpaying music artists. It hopes to change that perception

Back in the early 2010s, the music industry was at a low point.

Piracy was rampant. Compact disc sales were on a steady decline. And the then-new audio streaming services, like Spotify, were taking hits from creators for paying low royalty rates.

Today, Spotify has grown into the world’s most popular audio streaming subscription service and the highest-paying retailer globally — paying the music industry over $11 billion last year. The Swedish company said in a recent post that the payouts aren’t strictly going to ultra-popular artists, but that “roughly half of royalties were generated by independent artists and labels.”

“A decade ago, a lot of the questions were really fair. Spotify had to be able to prove out if it could scale as an economic engine. People didn’t know if streaming would scale as a model,” said Sam Duboff, Spotify’s global head of marketing and policy of music business.

Duboff said Spotify’s payouts aren’t “plateauing — we’re still growing that royalty pool on Spotify more than 10% per year.” He credits the streaming platform’s growth to “incentivizing people to be willing to pay for music again” by providing personalized experiences and global accessibility.

The company, founded in 2006, serves more than 751 million users, including 290 million subscribers, in 184 markets.

“The average Spotify premium subscriber listens to 200 artists every month, and nearly half of those artists are discovered for the first time,” Duboff said. “When you build an experience where people can explore and fall in love with music, it inspires them to upgrade to premium and keep paying.”

The platform offers a wide variety of playlists, curated by editors like the up-and-comer-driven Fresh Finds or rap’s latest, RapCaviar. There are also personal playlists generated for users, such as the weekly round-up Discover Weekly and the daily mix of tunes called the “daylist.”

The streamer considers itself the first step toward “an enduring career” for today’s indie artists. Last year, more than a third of artists making $10,000 on the platform in royalties started by self-releasing their music through independent distributors.

“Streaming, fundamentally, is about opportunity and access. It’s artists from all over the world releasing music the way they want to and reaching a global audience from Day One,” Duboff said. He adds that when fans have a choice, they will discover new genres and music cultures that may have otherwise languished in obscurity.

In 2025, nearly 14,000 artists earned $100,000 from Spotify alone. The streamer’s data also show that last year the 100,000th highest-earning artist made $7,300 in Spotify royalties, whereas in 2015, an artist in that same spot earned around $350.

The company, with a large presence in L.A.’s Arts District, emphasizes that the roster of artists on its platform who earn significantly more money — well into the millions — is no longer limited to the few. A decade ago, Spotify’s top artist made around $10 million in royalties. Today, the platform’s top 80 artists generate over $10 million annually. Some of 2025’s top artists globally were Bad Bunny, Taylor Swift and the Weeknd.

Spotify claims those who aren’t household names can earn six figures, with more than 1,500 artists earning $1 million last year.

For some musicians, the outlook is not as clear

Damon Krukowski, a musician and the legislative director for United Musicians & Allied Workers, argues that Spotify’s money isn’t necessarily going to artists — it’s going to their labels.

Those without labels usually upload music through distributors such as DistroKid and CD Baby. These platforms charge a small fee or commission. For example, DistroKid’s lowest-level subscription is $24.99 a year, and the site states users “keep 100% of all your earnings.”

”There are zero payments going directly to recording artists from Spotify,” Krukowski asserts. “Recording artists deserve direct payment from the streaming platforms for use of our work.”

The advocacy group, which has mobilized more than 70,000 musicians and music workers, recently helped draft the Living Wage for Musicians Act to address the streaming industry. The bill, introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives last fall, calls for a new streaming royalty that would directly pay artists a minimum of one penny per stream.

In the Q&A section of Spotify’s Loud and Clear website, the streamer confirms that it “doesn’t pay artists or songwriters directly. We pay rights holders selected by the artist or songwriter, whether that’s a record label, publisher, independent distributor, performance rights organization, or collecting society.”

Instead of following a penny-per-stream model, Spotify pays based on the artist’s share of total streams, called a “streamshare.”

“Streaming doesn’t work like buying songs. Fans pay for unlimited access, not per track they listen to,” wrote the company online. “So a ‘per stream’ rate isn’t actually how anyone gets paid — not on Spotify, or on any major streaming service.”

Movie Reviews

‘Project Hail Mary’ Review: Ryan Gosling and a Rock Make Sci-Fi Magic

In contrast to other sci-fi heroes, like Interstellar’s Cooper, who ventures into the unknown for the sake of humanity and discovery, knowing the sacrifice of giving up his family, Grace is externally a cynical coward. With no family to call his own, you’d think he’d have the will to go into space for the sake of the planet’s future. Nope, he’s got no courage because the man is a cowardly dog. However, Goddard’s script feels strikingly reflective of our moment. Grace has the tools to make a difference; the Earth flashbacks center on him working towards a solution to the antimatter issue, replete with occasionally confusing but never alienating dialogue. He initially lacks the conviction, embodying a cynicism and hopelessness that many people fall into today.

The film threads this idea effectively through flashbacks that reveal his reluctance, giving the story a tragic undercurrent. Yet, it also makes his relationship with Rocky, the first living thing he truly learns to care for, ever more beautiful.

When paired with Rocky, Gosling enters the rare “puppet scene partner” hall of fame alongside Michael Caine in The Muppet Christmas Carol, never letting the fact that he’s acting opposite a puppet disrupt the sincerity of his performance. His commitment to building a gradual, affectionate friendship with this animatronic creation feels completely natural, and the chemistry translates beautifully on screen. It stands as one of the stronger performances of his career.

Project Hail Mary is overly long, and while it can be deeply affecting, the film leans on a few emotional fake-outs that become repetitive in the latter half. By the third time it deploys the same sentimental beat, the effect begins to feel cloying, slightly dulling the powerful emotions it built earlier. The constant intercutting between past and present can also feel thematically uneven at times, occasionally undercutting the narrative momentum. At 2 hours and 36 minutes, the film feels like it’s stretching itself to meet a blockbuster runtime when a tighter cut might have served better.

FINAL STATEMENT

Project Hail Mary is a meticulously crafted, hopeful, and dazzling space epic that proves the most moving friendship in film this year might just be between Ryan Gosling and a rock.

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Pennsylvania6 days ago

Pennsylvania6 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Detroit, MI5 days ago

Detroit, MI5 days agoU.S. Postal Service could run out of money within a year

-

Miami, FL7 days ago

Miami, FL7 days agoCity of Miami celebrates reopening of Flagler Street as part of beautification project

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death

-

Virginia7 days ago

Virginia7 days agoGiants will hold 2026 training camp in West Virginia

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on the Real Locations in These Magical and Mysterious Novels