Entertainment

Poet and activist Nikki Giovanni, the 'Princess of Black Poetry,' dies at 81

Poet and civil rights activist Nikki Giovanni, a prominent figure during the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s and ‘70s who was dubbed “the Princess of Black Poetry,” has died. She was 81.

Giovanni died “peacefully” Monday with life partner Virginia “Ginney” Fowler by her side, her friend and author Renée Watson said Tuesday in a statement to The Times. She had recently been diagnosed with cancer for the third time, Watson said.

“We will forever feel blessed to have shared a legacy and love with our dear cousin,” Giovanni’s cousin Allison “Pat” Ragan added in a statement on behalf of the family.

Watson and author-poet Kwame Alexander said that they, along with with family and close friends, recently sat by Giovanni’s side “chatting about how much we learned about living from her, about how lucky we have been to have Nikki guide us, teach us, love us.”

“We will forever be grateful for the unconditional time she gave to us, to all her literary children across the writerly world,” Alexander said in the statement.

Giovanni, born Yolande Cornelia Giovanni Jr., used her voice as a poet to address issues of Black identity and Black liberation. She was best known for her outspoken advocacy and her charismatic delivery and was a friend of fellow wordsmiths Maya Angelou, Sonia Sanchez, Gwendolyn Brooks, James Baldwin and Toni Morrison. She also became friendly with other cultural iconoclasts, including Rosa Parks, Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone and Muhammad Ali.

“My dream was not to publish or to even be a writer: my dream was to discover something no one else had thought of. I guess that’s why I’m a poet. We put things together in ways no one else does,” Giovanni wrote on her website.

Named after her mother, Giovanni was born June 7, 1943, in Knoxville, Tenn. She had an older sister, Gary Ann. Her family later moved north, and she spent most of her childhood in Cincinnati — a period she described in her writing as turbulent because her father was physically abusive to her mother.

Giovanni returned to Nashville in 1961 to attend Fisk, a historically Black university, where she studied history. A voracious reader since girlhood, she was admitted early, before she finished high school. Giovanni edited the university’s literary magazine and helped start the campus branch of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Associated Press said.

But she was expelled after just one semester because of her contentious relationship with one of the the school’s deans due to her political activism and opposition to the school’s stern rules and curfew. Three years later, she re-enrolled under a new dean, who agreed to wipe her record clean.

She completed her degree in 1967 and moved back to Cincinnati, where she edited a local art journal and organized Cincinnati’s first Black Arts Festival.

In 1968, she self-published her first volume of poetry, “Black Feeling Black Talk / Black Judgement.” Her poems grew out of her feelings about the assassinations of civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers and Malcolm X and the death of her grandmother.

In one of Giovanni’s early poems, “Reflections on April 4, 1968,” marking the day King was assassinated, she wrote, “What can I, a poor Black woman, do to destroy America? This / is a question, with appropriate variations, being asked in every / Black heart.” Her other works, including “A Short Essay of Affirmation Explaining Why,” “Of Liberation” and “A Litany for Peppe,” were described by the AP as militant calls to overthrow white power.

In addition to her adult poetry, she released two films, 13 children’s poetry books and 10 recordings, including her Grammy-nominated “The Nikki Giovanni Poetry Collection.” She was a frequent guest on the PBS talk show “Soul.” A film about her life, “Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project,” won the U.S. Grand Jury Prize for documentary at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2023. The film utilizes vérité and archival images to give audiences a glimpse into Giovanni’s mind.

“A poem is not so much read as navigated,” Giovanni wrote in her in 2013 book “Chasing Utopia.” “We go from point to point discovering a new horizon, a shift of light or laughter, an exhilaration of newness that we had missed before. Even familiar, or perhaps especially familiar, poems bring the excitement of first nighters, first encounters, first love … when viewed and reviewed.”

After teaching at a few universities domestically and guest lecturing abroad, she was recruited by an English professor named Virginia Fowler to teach creative writing at Virginia Tech.

“We are deeply saddened to learn of Nikki Giovanni’s passing,” the university said Tuesday on X (formerly Twitter). “Nikki will be remembered not only as an acclaimed poet and activist but also for the legendary impact she made during her 35 years at Virginia Tech.”

Nikki Giovanni recites her poem “We Are Virginia Tech” during the May 2007 English department graduation ceremony on the campus of Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va.

(Steve Helber / Associated Press)

In 2007, that university became the site of one of the most deadly shootings in U.S. history, with 32 people killed and 17 injured on campus. The gunman — who was also killed — was a former student of Giovanni’s, and she had alerted school authorities previously about his troubling behavior in her class. Giovanni, a former creative writing instructor, said she took some of his writing to the school’s dean and told the dean that she could no longer teach him.

After the tragedy, she was instrumental in rallying people and restoring a sense of morale to a traumatized student body.

“I couldn’t allow him to destroy my class,” she told The Times in 2007. She delivered part of the convocation address at graduation that school year to roaring applause.

“We will prevail! / We will prevail! / We will prevail! / We are Virginia Tech,” she said at the ceremony.

As her spouse, Fowler has become an expert and keeper of Giovanni’s work and legacy. In an interview with the Fight and the Fiddle, Giovanni described how Fowler was an important pillar of support and that she was “so lucky to have found Ginny.”

“Her grandmother was the most important person to her,” Fowler said. “Their home in Cincinnati wasn’t happy because Nikki discovered that she would have to leave or she would have to kill [her father]. She went to live with her grandmother. She asked if she could stay.”

As Giovanni lived, so she wrote. She broke with cultural norms and gave birth to her only child, Thomas Watson Giovanni, in 1969, when she was 25 because “wanted to have a baby and I could afford to have a baby.” She told Ebony magazine that she didn’t want to get married and “could afford not to get married.” In her 1971 extended autobiographical statement, “Gemini,” she detailed her life growing up as a young single mother, which was taboo at the time.

Nikki Giovanni appears at the 2015 unveiling of the U.S. Postal Service’s Maya Angelou Forever Stamp in Washington, D.C.

(Jacquelyn Martin / Associated Press)

“Her life is the life of Black people,” said L. Lamar Wilson, who was mentored by Giovanni. “She documented it in every art form: film, television … from the 1940s to the present.” Wilson is now a published poet and professor at Florida State University.

Wilson was a reporter and copy editor working at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution when he made the case to report on Giovanni’s appearance in the city in 2007. During their interview, she stopped him and invited him to apply to the creative writing master’s program at Virginia Tech.

“Nikki changed the trajectory of my life. And I’m one of at least 25 people I could name to you who are very famous prominent writers who have the same story,” he said. “She has mentored us, she has been our friend, she has been our surrogate mother when we needed it. She has been our disciplinarian when we needed it, cautioning us about the pitfalls and the pratfalls of the publishing industry and of academia.”

As an educator, Giovanni is crediting with helping usher in a younger generation of Black writers.

Giovanni planned a celebration for “The Bluest Eye” author Morrison before the latter died in 2019. At the celebration, people read their favorite excerpts from her work, moving Morrison to tears.

As a winner of seven NAACP awards and countless more accolades for her achievements in poetry — Giovanni helped up-and-coming writers.

“I think she’s proudest of having opened the door for a lot of future … writers who came after her. They were able to come after her because she had opened doors,” Fowler said. “She is generous, she helps other people, she’s helped other artists, and that’s pretty unusual.”

In 2015, Times columnist Sandy Banks interviewed Giovanni on the heels of the Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, Mo.

“I’m not a guru. I don’t have the answers,” Giovanni said when Banks asked about guidance for young writers. “Just trust your own voice. And keep exploring the things that are interesting to you.

“All I can do is be a good Nikki. All you can do is be you,” she said.

Nikki Giovanni delivers closing remarks at a Virginia Tech convocation to honor victims of a mass shooting on the campus in 2007.

(Steve Helber / Associated Press)

Longtime friend Joanne Gabbin — executive director of Furious Flower, the nation’s first academic center for Black poetry — believes Giovanni was proudest of her relationship with her grandmother. “Family is very important. I think it goes all the way back to what her grandmother shared with her, what her grandmother taught her, the values that her grandmother instilled in her,” Gabbin told The Times. “She had made a commitment to her grandmother that whatever she did, it would be excellent.”

In 2016, Gabbin and Giovanni, who had been friends for more than 30 years, were given a preview opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Gabbin said that while touring the museum, Giovanni encountered a “huge kind of a portrait” of herself displayed in the exhibit, marked in history as a literary legend.

Giovanni is survived by Fowler; her son, Thomas; and her granddaughter, Kai.

Kayembe is a former Times fellow. The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Movie Reviews

‘Project Hail Mary’ Review: Ryan Gosling and a Rock Make Sci-Fi Magic

In contrast to other sci-fi heroes, like Interstellar’s Cooper, who ventures into the unknown for the sake of humanity and discovery, knowing the sacrifice of giving up his family, Grace is externally a cynical coward. With no family to call his own, you’d think he’d have the will to go into space for the sake of the planet’s future. Nope, he’s got no courage because the man is a cowardly dog. However, Goddard’s script feels strikingly reflective of our moment. Grace has the tools to make a difference; the Earth flashbacks center on him working towards a solution to the antimatter issue, replete with occasionally confusing but never alienating dialogue. He initially lacks the conviction, embodying a cynicism and hopelessness that many people fall into today.

The film threads this idea effectively through flashbacks that reveal his reluctance, giving the story a tragic undercurrent. Yet, it also makes his relationship with Rocky, the first living thing he truly learns to care for, ever more beautiful.

When paired with Rocky, Gosling enters the rare “puppet scene partner” hall of fame alongside Michael Caine in The Muppet Christmas Carol, never letting the fact that he’s acting opposite a puppet disrupt the sincerity of his performance. His commitment to building a gradual, affectionate friendship with this animatronic creation feels completely natural, and the chemistry translates beautifully on screen. It stands as one of the stronger performances of his career.

Project Hail Mary is overly long, and while it can be deeply affecting, the film leans on a few emotional fake-outs that become repetitive in the latter half. By the third time it deploys the same sentimental beat, the effect begins to feel cloying, slightly dulling the powerful emotions it built earlier. The constant intercutting between past and present can also feel thematically uneven at times, occasionally undercutting the narrative momentum. At 2 hours and 36 minutes, the film feels like it’s stretching itself to meet a blockbuster runtime when a tighter cut might have served better.

FINAL STATEMENT

Project Hail Mary is a meticulously crafted, hopeful, and dazzling space epic that proves the most moving friendship in film this year might just be between Ryan Gosling and a rock.

Entertainment

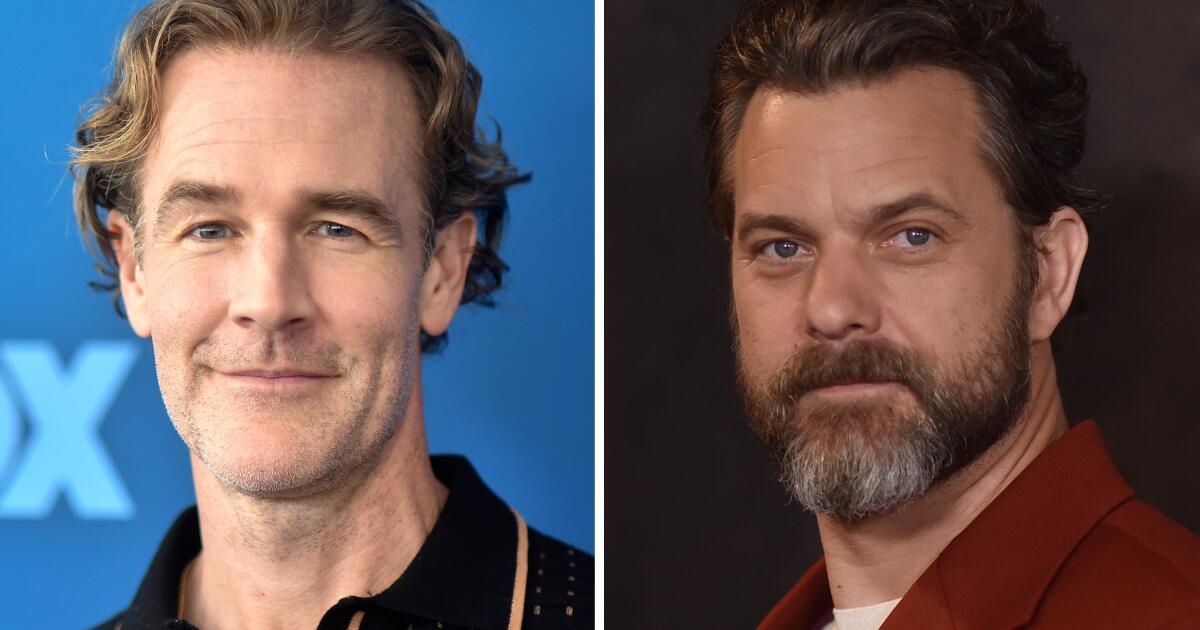

James Van Der Beek ‘became what we used to just call a good man,’ Joshua Jackson says

Joshua Jackson says he knows he was “really just a footnote” in James Van Der Beek’s life, despite the “amazing” time they spent together as stars of the series “Dawson’s Creek.”

The star of “The Affair” is reflecting publicly for the first time about his former castmate, who died Feb. 11 at age 48 after a battle with colorectal cancer.

The time they shared on set was “formational” for them, Jackson said on “Today.” When the “Dawson’s Creek” pilot aired in January 1998, he was 19 and Van Der Beek was almost 21, playing characters who were 15.

“I know both of us look back on that time with great fondness, but I will also say that I know that I’m really just a footnote in what he actually accomplished in his life.”

Jackson spoke with great respect for his friend, who he said “became what we used to just call a good man, a man of the kind of belief, the kind of faith that allowed him to face the impossible with grace, an unbelievable partner and husband, just a real man who showed up for his family and a beautiful, kind, curious, interested, dedicated father.”

On the one hand, the 47-year-old said, “that’s beautiful.” On the other, “The tragedy of that loss for his family is enormous.”

Since Jackson and Van Der Beek played Pacey Witter and Dawson Leery three decades ago, both men had kids of their own — a 5-year-old daughter for Jackson, born during the pandemic with ex-wife Jodie Turner-Smith, and six kids for Van Der Beek with second wife Kimberly Brook. The latter couple’s children — two boys and four girls, ranging in age from 4 to 15 — were what Van Der Beek said changed everything for him.

“Your life becomes shared, and your joys become shared joys in a really beautiful way that expands your level of circuitry out to other people instead of just keeping it all for your own gratification,” the actor told “Good Morning America” in May 2023. “And the lessons, they keep on coming. It’s the craziest, craziest thing I’ve ever done, and it’s the thing that’s made me happiest.”

Knowing his colleague’s love for his family, Jackson said on “Today” that “for me as a father now, I think the enormity of that tragedy hits me in a very different way than just as a colleague, so I think the processing [of Van Der Beek’s death] is ongoing.”

The “Little Fires Everywhere” actor was on the morning show Tuesday to bring attention to colorectal cancer screenings.

Van Der Beek’s diagnosis, which went public in November 2024, was among the factors prompting Jackson to get involved with drugmaker AstraZeneca’s “Get Body Checked Against Cancer” campaign, which takes a lighter approach to a serious subject — cancer screening — through a partnership with Jackson, the National Hockey League and the Philadelphia Flyers’ furry orange mascot, Gritty.

“It is … true, the earlier you find something,” said “The Mighty Ducks” actor, “the better your possible outcomes are.”

Movie Reviews

Dan Webster reviews “WTO/99”

DAN WEBSTER:

It may now seem like ancient history, especially to younger listeners, but it was only 26 years ago when the streets of Seattle were filled with protesters, police and—ultimately—scenes of what ended up looking like pure chaos.

It is those scenes—put together to form a portrait of what would become known as the “Battle of Seattle” —that documentary filmmaker Ian Bell captures in his powerful documentary feature WTO/99.

We’ve seen any number of documentaries over the decades that report on every kind of social and cultural event from rock concerts to war. And the majority of them follow a typical format: archival footage blended with interviews, both with participants and with experts who provide an informational, often intellectual, perspective.

WTO/99 is something different. Like The Perfect Neighbor, a 2026 Oscar-nominated documentary feature, Bell’s film consists of what could be called found footage. What he has done is amass a series of news reports and personal video recordings into an hour-and-42-minute collection of individual scenes, mostly focused on a several-block area of downtown Seattle.

That is where a meeting of the WTO, the World Trade Organization, was set to be held between Nov. 30 and Dec. 3, 1999. Delegates from around the world planned to negotiate trade agreements (what else?) at the Washington State Convention and Trade Center.

Months before the meeting, however, a loose coalition of groups—including NGOs, labor unions, student organizations and various others—began their own series of meetings. Their objective was to form ways to protest not just the WTO but, to some of them, the whole idea of a world order they saw as a threat to the economic independence of individual countries.

Bell’s film doesn’t provide much context for all this. What we mostly see are individuals arguing their points of view as they prepare to stop the delegates from even entering the convention center. Meanwhile, Seattle authorities such as then-Mayor Paul Schell and then-Police Chief Norm Stamper—with brief appearances by Gov. Gary Locke and King County Executive Ron Sims—discuss counter measures, with Schell eventually imposing a curfew.

That decision comes, though, after what Bell’s film shows is a peaceful protest evolving into a street fight between people parading and chanting, others chained together and splinter groups intent on smashing the storefronts of businesses owned by what they see as corporate criminals. One intense scene involves a young woman begging those breaking windows to stop and asking them why they’re resorting to violence. In response a lone voice yells their reasoning: “Self-defense.”

Even more intense, though, are the actions of the Seattle police. We see officers using pepper spray, tear gas, flash grenades and other “non-lethal” means such as firing rubber pellets into the crowd. In one scene, a uniformed guy—not identified as a police officer but definitely part of the security crowd, which included National Guardsmen—is shown kicking a guy in the crotch.

The media, too, can’t avoid criticism. Though we see broadcast reporters trying to capture what was happening—with some affected like everybody else by the tear gas that filled the streets like a winter fog—the reports they air seem sketchy, as if they’re doctors trying to diagnose a serious illness by focusing on individual cells. And the images they capture tend to highlight the violence over the well-meaning actions of the vast majority of protesters.

Reactions to what Bell has put on the screen are bound to vary, based on each viewer’s personal politics. Bell revels his own stance by choosing selectively from among thousands of hours of video coverage to form the narrative he feels best captures what happened those two decades-and-change ago.

If nothing else, WTO/99 does reveal a more comprehensive picture of what happened than we got at the time. And, too, it should prepare us for the future. The way this country is going, we’re bound to see a lot more of the same.

Call it the “Battle for America.”

For Spokane Public Radio, I’m Dan Webster.

——

Movies 101 host Dan Webster is the senior film critic for Spokane Public Radio.

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Pennsylvania5 days ago

Pennsylvania5 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Detroit, MI5 days ago

Detroit, MI5 days agoU.S. Postal Service could run out of money within a year

-

Miami, FL6 days ago

Miami, FL6 days agoCity of Miami celebrates reopening of Flagler Street as part of beautification project

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death