Movie Reviews

Blitz movie review: the unraveling of propaganda – FlickFilosopher.com

Blitz opens amidst a terrifying conflagration on a nighttime city street. This is the blitzkrieg, the German bombing of London in 1940 in the early days of World War II. But as writer-director Steve McQueen casts it, it’s not about an entire street or even a single building on fire. It’s about a loose fire hose whipping about wildly and the heavy industrial nozzle whacking an anonymous fireman in the head as he struggles to bring it under control.

It’s a moment of feral intensity, and of ferocious intimacy. It reminded me of nothing so much as snippets from early in the TV series Chernobyl, about the 1986 nuclear-plant disaster. Just an ordinary schmoe firefighter not even thinking twice about doing a dangerous job, because it has to be done.

Blitz is not about that firefighter. But the brutal randomness of that opening sequence sets the stage for what is to come. This is not a sentimental story about British stiff upper lips and keeping calm and carrying on. There were scenes in this movie when I gasped out loud and actually clapped a hand to my mouth in shock — I can’t recall if I’d ever done that before. McQueen (Widows, Shame) seems to be deliberately pushing back against how the British and especially the London experience of the war has been ex post facto propagandized into cheery, chipper camaraderie and complacency. Indeed, the whole “keep calm and carry on” thing was a propaganda slogan developed during the war but barely used then, and was almost entirely forgotten until it was rediscovered in 2000 and subsequently weaponized for whitewashed and commercialized nostalgia.

McQueen plays with those expectations but smashes them at every opportunity with this tale of nine-year-old George, who’s furious that his single mom, Rita, has relented and agreed to evacuate her son to the countryside, finally, after so many other London children had already left. Blitz is the picaresque misadventures of George as he decides to take himself home, Nazi bombs be damned, and to the inadvertent horror of his mother, once she is informed that the authorities who were supposed to be in charge of George’s safety have lost him.

(George is played by wonderful newcomer Elliott Heffernan, a real find on McQueen’s part. Rita is portrayed by Saoirse Ronan [Foe, Little Women], as ever a standout, and the best thing even in an all-around terrific movie, as this is.)

McQueen is pushing back against another sort of whitewashing, too, of the more literal kind: the bizarre notion that, somehow, “diversity” is a 21st-century invention and that people of color haven’t always been a part of, in particular, majority-white colonial nations like Great Britain. (This is hugely applicable to the US as well.) The filmmaker had said he was inspired in this story by an old photograph of a mixed-race Blitz evacuee, a small boy standing on a WWII-era railway platform, and wondered what his life was like. And so McQueen — who is Black British — builds a sketch of vibrant, multicultural life in century-ago London. Partly through flashbacks, of the lively jazz-club scene where Rita partied, pre-war, with George’s father, Marcus (CJ Beckford), an immigrant from Grenada who is no longer in the picture. But McQueen’s portrait of a London that some would like to pretend never existed blossoms, enormously affectingly, via the air-raid warden George encounters on his journeys: Ife (Benjamin Clémentine: Dune), a Nigerian immigrant to London. Sharply but gently — so gently: Ife is one of the loveliest characters I’ve met onscreen in a long while — McQueen’s exuberant, diverse London subtly suggests that this, very much this, is what was worth fighting the Nazis to protect.

(Relevance to today? Sky-high, no pun intended. It was WWII horrors like the Blitz, as well as the Allied firebombing of Dresden, in Germany, and the American atomic attacks on Japan that have helped shaped our ideas about what constitutes warcrimes today. Bonus points to anyone who can pinpoint multiple indiscriminate military attacks on civilians happening right now around the planet.)

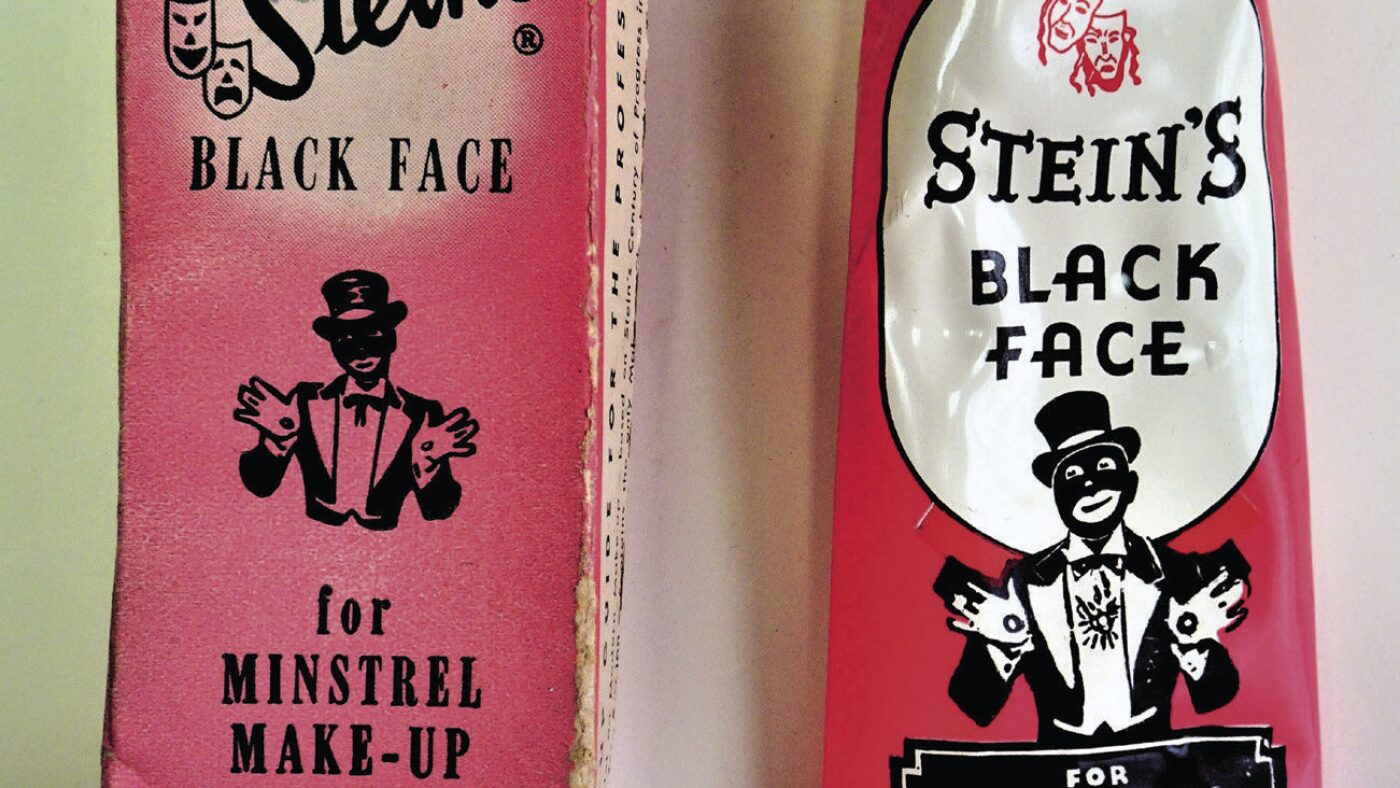

Yet nothing here is romanticized, either. Racism is a real and pervasive presence — the sequence in which George has his eyes opened to just how ingrained the denigration of Black people has been by the British Empire is heartbreaking — as is the opportunism of those who would take advantage of the chaos of the Blitz: Stephen Graham (Boiling Point, Greyhound) and Kathy Burke (Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie, Pan) as scavenger-thieves who descend after the bombs fall, and who rope George into their schemes, are terrifying, akin to the Thenardiers of Les Misérables but devoid of their bleak comedy.

Blitz is McQueen’s most accessible, most mainstream film yet; his previous works include 2010’s IRA hunger-strike movie Hunger, 2013’s 12 Years a Slave, and last year’s Occupied City, a four-and-a-half-hour documentary about Nazi-occupied Amsterdam. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t absolutely brutal. This is a movie about childhood adventure that is a lark, until it isn’t. It’s about community care and small moments of kindness from strangers in passing, and also about stomping on your neighbors in moments of panic and terror. It’s wildly human, artistically masterful, and completely magnificent.

more films like this:

• Empire of the Sun [Prime US | Prime UK | Apple TV]

• 12 Years a Slave [Prime US | Prime UK | Apple TV | Netflix UK (till Nov 15) | BFI Player UK]

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: “THE BRIDE!” – Assignment X

By ABBIE BERNSTEIN / Staff Writer

Posted: March 8th, 2026 / 08:00 PM

THE BRIDE movie poster | ©2026 Warner Bros.

Rating: R

Stars: Jessie Buckley, Christian Bale, Annette Bening, Jake Gyllenhaal, Peter Sarsgaard, Penelope Cruz, Jeannie Berlin, Zlatko Burić

Writer: Maggie Gyllenhaal, based on characters created by Mary Shelley and William Hurlbut and John Balderston

Director: Maggie Gyllenhaal

Distributor: Warner Bros.

Release Date: March 6, 2026

“THE BRIDE!” (as with the recent “WUTHERING HEIGHTS,” the quotation marks are part of the title) is awash in homages, and not just the ones we might reasonably expect in a movie that takes its most obvious inspiration from 1935’s BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN.

There’s that, of course, plus its source, Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel FRANKENSTEIN; OR THE MODERN PROMETHEUS, and its sober 1931 film adaptation FRANKENSTEIN. But there are also big nods to wilder takes on the legend, including YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN and THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW and even movies that have nothing to do with FRANKENSTEIN, like BONNIE AND CLYDE.

Writer/director Maggie Gyllenhaal casts a wide net in metaphors and ideas and looks. Sometimes “THE BRIDE!” is a comedy, sometimes it’s a crime drama, sometimes it’s a love story, occasionally, it’s even a musical.

Mary Shelley (Jessie Buckley) narrates the tale to us from beyond the grave. She is haughty and naughty, intoxicated by verbiage and her own literary genius. She is going to tell us a story, she says, that she didn’t even dare imagine while alive.

We’re in 1930s Chicago, where a young escort (also Buckley) is having a really awful evening out at a fancy restaurant with some of her peers and a bunch of crass gangsters. Shelley dubs the woman “Ida” and takes possession of her, causing her to speak and act in ways that get her escorted outside. There she stumbles and takes a fatal fall.

The two goons who were with Ida are happy to describe her tumble as the result of their intentional actions to their horrible gangster boss (Zlatko Burić). Ida was suspected of talking to the cops.

Around the same time, Frankenstein’s creation (Christian Bale) – let’s just call him “Frank,” like everybody else does – comes to Chicago to seek out the groundbreaking scientist Dr. Euphronious (Annette Bening), whose published works he has read.

Frank wants the doctor to create a companion for him. His appearance is unusual, but the most alarming injuries are covered by clothing, so he’s not as extreme-looking as, say, Boris Karloff in the role. This isn’t about sex, Frank explains when Euphronious asks why he doesn’t just hire a prostitute. After over a century of loneliness, he seeks a soulmate, and he is sure this can only be achieved by reviving a corpse.

So, Euphronious and Frank dig up the grave that turns out to belong to Ida (we never do learn how they know it belongs to a soulmate candidate as opposed to a shot-and-dumped male gangster). Euphronius revives her. Ida remembers how to walk and talk, but not who she is or what happened, so Frank and the doc tell her she’s been in an accident.

Even without Ida’s beauty, Frank is already devoted to the very notion of her. A more accommodating suitor would be hard to find. Frank has another passion, the musical films of Ronnie Reed (Jake Gyllenhaal, the filmmaker’s brother), a Fred Astaire-like star. Frank imagines himself in the midst of those dance routines, and we get some more within “THE BRIDE!”’s “real” action.

One thing leads to another, Frank and Ida go on the run, leaving a trail of bodies in their wake. They are pursued all over the country. Among those seeking them are sad-eyed police detective Jake Wiles (Peter Sarsgaard) and his secretary Myrna Mallow (Penélope Cruz), who’s better at this whole crime-solving business than he is.

It’s all very kaleidoscopic and energetic, occasionally impressive and sometimes very funny. Bening as the frazzled, worldly Euphronious has some great moments. Buckley, currently and justifiably Oscar-nominated leading performance in HAMNET, juggles the very unalike personas of Mary and Ida with impact.

Oddly, Bale underplays Frank. We get that he is trying his hardest not to spook Ida (or anyone else), but it seems like he should have a bit more spark. Cruz, going for a snappy ‘30s working woman, has her own style that works.

But in addition to being entertaining and eye-catching, Gyllenhaal has a message that gets very muddled. This is less because it’s so familiar by now that it feels a little redundant, and more because a crucial part of the set-up collides head-on with the feminist slant.

Ida seeks to be her own person, but she is literally bodily controlled by Mary Shelley, who puts her creation in danger with her outbursts. This may help get Ida out of the clutches of the mob, but it is possession, the aftereffects of which the character understandably finds confusing and upsetting.

If Gyllenhaal wanted to discuss or dramatize the clash between what Mary, as a woman, is doing to this other woman, that would make sense, but it seems we’re just meant to somehow overlook this while being immersed in how men control women. The resulting cognitive dissonance adds another layer to a movie that already has more than it can comfortably service.

Additionally, when Mary has one of her outbursts while inhabiting Ida, the plot comes to a screeching halt until she’s finished. Many viewers will wish Mary would stop declaiming and just let Ida be herself.

“THE BRIDE!” succeeds in being trippy and some of it is memorable. By the end, though, it is more disjointed than even a movie about experiments and a character made up of multiple people’s body parts ought to be.

Related: Movie Review: NFT: CURSED IMAGESRelated: Movie Review: SCREAM 7

Related: Movie Review: OPERATION TACO GARY’S

Related: Movie Review: ANACORETA

Related: Movie Review: THIS IS NOT A TEST

Related: Movie Review: GHOST TRAIN

Related: Movie Review: COLD STORAGE

Related: Movie Review: THE HAUNTED FOREST

Related: Movie Review: “WUTHERING HEIGHTS”

Related: Movie Review: THE MORTUARY ASSISTANT

Related: Movie Review: THE STRANGERS: CHAPTER 3

Related: Movie Review: PILLION

Related: Movie Review: JIMPA

Related: Movie Review: ISLANDS

Related: Movie Review: WORLDBREAKER

Related: Movie Review: MOTHER OF FLIES

Related: Movie Review: 28 YEARS LATER: THE BONE TEMPLE

Related: Movie Review: NIGHT PATROL

Related: Movie Review: THE CONFESSION (2026)

Related: Movie Review: WE BURY THE DEAD

Related: Movie Review: ANACONDA

Related: Movie Review: AVATAR: FIRE AND ICE

Related: Movie Review: IS THIS THING ON?

Related: Movie Review: MANOR OF DARKNESS

Related: Movie Review: DUST BUNNY

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X

Article: Movie Review: “THE BRIDE!”

Related

Related Posts:

Movie Reviews

‘Heel’ Review: Why Did Stephen Graham and Andrea Riseborough Sign on for This Contrived Debacle?

The original title of “Heel” was “Good Boy.” The new title is probably more accurate, though an even more accurate title might be “Painfully Annoying Punk Idiot.” I jest (a bit), since the title of “Heel” is actually a verb. The film wants to tell the story of a budding hooligan who needs to be brought to heel. That said, does anyone seriously want to see a movie about a 19-year-old British sociopath who gets chained up in a basement so that the weird upper-middle-class couple who’ve kidnapped him can modify his behavior? “Heel” is like “A Clockwork Orange” remade as the year’s worst Sundance movie.

The opening sequence is actually promising. It depicts, in rapidly edited documentary-like montage, a reckless night out on the town by Tommy (Anson Boon) and his friends. They’re hopped-up club kids, and Tommy is their snarling, curly-haired, sexually coercive wastrel ringleader, living in the moment, pouring drinks down his throat, snorting coke and popping pills, dancing and carousing and puking and rutting in the bathroom, pushing himself to a higher and higher high, until he winds up collapsed on the sidewalk — a ritual, we gather, that has happened many times before. Only this time his crumpled body is gathered up by a mysterious stranger.

When Tommy wakes up, he’s in the basement of a stately stone house somewhere in the British countryside. He’s got a metal collar around his neck, and it’s chained to the ceiling. The film has barely gotten started, and already it’s cut to the second half of “A Clockwork Orange”: Can this monster delinquent be rehabilitated? Theoretically, that’s an interesting question, except that the way this happens is so garishly contrived that we can only go with the movie by putting any plea for reality on permanent hold.

Who are the people who have kidnapped Tommy? Chris (Stephen Graham) is a mild chap in a toupee who goes about his mission with a puckish vengeance disguised as gentility. His wife, Kathryn (Andrea Riseborough), is so neurasthenic she’s like a ghost. (She has suffered some trauma that isn’t colored in.) The two have a cherubic preteen son they call Sunshine (Kit Rakusen). And why, exactly, are they doing what they’re doing? We have no idea. Trying to make a bad person into a good person is not, in itself, a terrible notion, but the conceit of “Heel” — that Tommy is locked in a dungeon, being treated like a dog, because that’s what it will take to change him — is like a toxic right-wing fantasy that the film somehow reconfigures into an implausible liberal “family” allegory.

Ah, plausibility! How unhip to gripe about the absence of it. Yet watching “Heel,” I found it impossible to suspend my disbelief for two seconds. The entire movie, directed by the Polish filmmaker Jan Komasa (“Corpus Christie”) from a script by Bartek Bartosik and Naqqash Khalid, is just a grimy monotonous conceit. It’s been thought out thematically but not in terms of recognizable human behavior. It’s like a film-student short stretched out to an agonizing 110 minutes.

Anson Boon, a charismatic actor who did an okay job of playing Johnny Rotten in Danny Boyle’s TV miniseries “Pistol” (though he never conjured Rotten’s homicidal gleam), infuses Tommy with a loutish energy that in the early scenes, at least, makes him a convincing candidate for either prison or the contemporary equivalent of shock therapy. And yet the character is exhaustingly obnoxious. As a filmmaker, Komasa doesn’t dramatize — he uses one-note traits to clobber the audience. Stephen Graham’s Chris is as quiet and circumspect as Tommy is abrasive. He tries to train Tommy by showing him motivational tapes, and by subjecting him to Tommy’s own depraved TikToks. He then rigs up an elaborate system of gutters on the ceiling so that Tommy, in his metal leash, can wander around the house, a sign that he’s been housebroken.

Tommy has to grow and change, since there wouldn’t be a movie otherwise. In the process, he gets less annoying but also less interesting, because “Heel” sentimentalizes his transformation. Komasa seems to have missed the key irony of “A Clockwork Orange”: that the behavior modification of Alex is as brutalizing as his original state of punk anarchy. In “Heel,” Tommy’s evolution is singularly unconvincing — by the end, he’s practically ready to be the suitor in a Jane Austen drama. But that’s all of a piece with a movie so false it puts the audience in the doghouse.

Movie Reviews

The Movie Rating Dilemma: Or How I Learned How to Value Ratings

The act of judging — of assigning value to someone or something based on performance — is probably as old as humanity itself. You can safely assume that even cavemen were sizing each other up: Who hunts better? Who builds the sturdier shelter? Who’s pulling their weight?

Formalized systems came much later. The Roman Empire famously popularized the thumbs up/thumbs down gesture during gladiatorial games — a blunt but effective metric. By the 18th century, academic institutions began standardizing numerical grading systems. The 19th century introduced letter grades. And by the early 20th century, film criticism had entered the chat, with newspapers like the New York Daily publishing some of the earliest recorded movie grades (at least according to a quick Google dive — so take that with a grain of salt).

Fast forward to the 1970s, and modern film criticism as we know it began to crystallize. Roger Ebert popularized the four-star system, while he and Gene Siskel turned the thumbs up/thumbs down into a cultural mainstay on their television show — perhaps subconsciously echoing those ancient Roman gestures.

Now, I could theoretically try to confirm whether the Roman inspiration was intentional. But seeing as both critics have passed on, the only way to do that would involve a séance — and if horror movies have taught us anything, that never ends well. Sure, some people claim they’ve used an Ouija board, and nothing happened. Good for them. With my luck, I’d end up summoning Pazuzu, Candyman, a Djinn, and Satan all at once. So that’s a hard pass.

Jokes aside, in the past decade — arguably since the moment movie ratings were invented — people have increasingly questioned their value in entertainment and beyond. Albums, films, TV shows, books: every score feels like a potential battleground. (I don’t spend much time in Goodreads comment sections, but I can only imagine.)

But where did it all probably begin?

The Rotten Tomatoes Effect

I still remember the first time I heard about Rotten Tomatoes. It was on a radio show I used to catch after school called La Hora Señalada (the Spanish title for “High Noon”), where two veteran critics would break down new releases and revisit older classics. Before every discussion, they’d reference “the Rotten Tomatoes score,” like it was some cinematic barometer of truth.

I didn’t actually visit the site back then. Internet access at home was spotty — dial-up at best, nonexistent at worst — and not exactly a priority when my family had bigger concerns. But even without browsing it myself, I grew up watching cinephiles treat the Tomatometer like gospel. A high percentage meant “good.” A low one meant “bad.” Simple as that.

Over the past decade, that perception seems to have intensified. The site has been around since 1998, but the explosion of high-speed internet, social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook, and the rise of online fandom culture amplified its influence. Suddenly, that big red or green number wasn’t just a reference point — it became ammunition in arguments.

So, how much should we actually care about it?

The answer isn’t straightforward.

First, it’s important to understand what that percentage represents. The Tomatometer isn’t an average movie rating — it’s the percentage of critics who gave the film a “fresh” (positive) review. That means a movie sitting at 80% doesn’t necessarily have critics raving about it. Many of those positive reviews could be modest 7/10s or 3.5/5s. The more telling metric is the smaller average rating number listed beneath the percentage — but let’s be honest, most people fixate on the big, bold score.

Filmmakers have criticized the site for oversimplifying complex critical opinions into a binary fresh/rotten system. And that critique isn’t entirely unfair. When nuanced reviews get distilled into a single color-coded badge, context gets lost.

Then there’s the audience score — which, at least historically, has been vulnerable to manipulation. The most infamous example came during the release of “Captain Marvel,” when organized groups review-bombed the film largely due to backlash against Brie Larson. The score plummeted before most people had even seen the movie. To their credit, Rotten Tomatoes implemented changes afterward to curb that kind of coordinated sabotage. Of course, the opposite phenomenon exists too: fans artificially inflating scores for films they love.

All of this reinforces one simple idea: the site is a reference point, not a verdict.

It can be useful — a quick snapshot of critical consensus — but it shouldn’t live on a pedestal. It can mislead. It can misrepresent nuance. And it absolutely may not reflect your own taste. There are plenty of low-rated films I adore. “Max Keeble’s Big Move” sits at 27%, and I’ll defend that gem every, any, what, where, why, when, and however time.

Another factor people rarely consider: critics are individuals with specific tastes. If a horror skeptic reviews a slasher or a rom-com enthusiast tackles an austere arthouse drama, their reaction may not align with your own sensibilities. That doesn’t make them wrong — it just means taste is subjective.

I believe the healthiest approach is to treat Rotten Tomatoes as a starting point. Read individual reviews. Seek out critics whose tastes align with yours. Cross-reference with other aggregators like Metacritic, which uses a weighted average system rather than a binary model. (Full disclosure: I haven’t relied on it heavily myself, but many cinephiles prefer its methodology.)

In the end, no percentage can replace your own experience. The most reliable metric will always be the one you assign after the credits roll.

Also Related to Movie Rating Dilemma: The Death of the Opening Weekend: What Actually Defines Success in Film Now

The Value

In preparation for this article, I ran a small poll — and the results were both surprising and completely predictable. Much like politics (and, frankly, everything else these days), people are deeply divided on how much value they place on ratings. What caught me off guard, though, was that after hundreds of votes, the majority leaned toward the “don’t care” camp.

That lines up with a noticeable trend on platforms like Letterboxd, where more and more users are ditching the traditional star system in favor of a simple “heart” — or nothing at all.

So why is that happening?

From the responses and patterns I observed, one recurring reason is fluidity. Many people say their film ratings change constantly in their heads. A movie that felt like a four yesterday might feel like a three-and-a-half next month. Updating scores repeatedly can become tedious, even exhausting. But the bigger issue seems to be perception. People worry — sometimes rightly so— that their ratings will be misinterpreted. For some, three stars is a solid, positive endorsement. For others, anything below four feels like a dismissal. That disconnect can spiral into unnecessary debates — or worse, online pile-ons.

Which brings me to what I like to call the comparison game.

This is where things get absurd. It’s when someone compares potatoes to lettuce. Sure, they both grow from the ground. They might share space on a burger plate. But beyond that? Completely different textures, flavors, and purposes.

Recently, I rated “Dhurandhar” four stars — the same score I gave “One Battle After Another.” A follower asked how I could possibly see those films as equals. But that’s the assumption baked into the comparison game: that identical ratings equal identical value. They don’t. One film might be a potato, the other a lettuce — or an apple. What do they meaningfully have to do with each other?

The root issue seems simple: people take their favorite art personally. If I love X and give it four stars, you’d better love it just as much — or at least rate it the “correct” way. Otherwise, the pitchforks come out. Disagreement isn’t just disagreement; it becomes a perceived attack.

And that’s where ratings shift from being shorthand expressions of personal taste to symbols people defend as if they were moral positions. In theory, a rating is just a snapshot of how something worked for one individual at one moment in time. In practice, it can feel like a referendum on identity.

Which says less about the numbers themselves — and more about how much we’ve invested in them.

When you rate a movie, do you stop and cross-reference every prior rating to ensure consistency across unrelated genres? The only time that kind of comparative calibration makes sense to me is within a contained body of work — ranking a director’s filmography, an actor’s performances, or entries in a franchise.

There are even stranger edge cases. I’ve given “The Room” a perfect score — not because it’s “objectively” great in a traditional sense, but because, for what it is, and what it accidentally achieves, it feels like a specific kind of perfection. Meanwhile, others might rate it a two-star disaster and still love it just as passionately. The number doesn’t always tell the whole emotional truth.

Now, for the positives.

As one commenter on the site put it, “rating forces us to confront the tough question: how much did this film really work for me?” A rating compels clarity. It forces you to distill your feelings into a decision.

In a way, this circles back to the heart-versus-stars debate. Clicking a heart on Letterboxd leaves a lot open to interpretation. Say you heart both “Dog Day Afternoon” and “12 Angry Men.” Great — but do you value them equally? Which one affected you more? Which one would you revisit first? Without a rating (or a detailed review), we’re left guessing.

And that ties into another undeniable reality: we’re living in a low-attention-span era. You can write a thoughtful, beautifully argued review — and many people simply won’t read it. On fast-scrolling platforms, especially, the rating becomes a kind of headline. A shorthand signal. It tells followers, at a glance, whether you found something worthwhile.

Conclusion

Personally, I’ll always champion ratings.

Yes, they’re a double-edged sword. They can flatten nuance, spark unnecessary outrage, or reduce complex feelings to a tidy number. But they can also serve a practical purpose — if we’re willing to understand how to read them. There’s probably an argument to be made that audiences need a bit more education on interpreting ratings as shorthand rather than gospel.

Some critics have come up with creative systems that embrace that shorthand in interesting ways. Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel boiled it down to the now-iconic thumbs metric — elegantly simple, instantly readable. Dan Murrell leans into a more textual breakdown, while Cody Leach blends a numbered score with contextual explanation. Different approaches, same goal: distilling a reaction into something digestible without (ideally) stripping it of meaning.

It’s not easy. The more you think about cinema as art — deeply personal, highly subjective — the more assigning it a number can start to feel reductive. For some critics, the very act of rating becomes a burden, as if they’re forced to quantify something that resists quantification.

Are ratings imperfect? Absolutely. Are they reductive? Sometimes. But they’re also efficient, clarifying, and — when used thoughtfully — a meaningful extension of the conversation rather than its replacement. In a media landscape built on quick takes and endless content, ratings function as a kind of necessary evil. They’re a snapshot, not the whole portrait. When used responsibly — and interpreted thoughtfully — they don’t have to replace the conversation. They can simply be the entry point to it.

Similar Read Around Movie Rating Dilemma: 9 Biggest Hollywood Box Office Bombs of 2025: Movies That Lost Millions Despite Huge Budgets

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Pennsylvania4 days ago

Pennsylvania4 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago2 Survivors Describe the Terror and Tragedy of the Tahoe Avalanche

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death

-

Virginia5 days ago

Virginia5 days agoGiants will hold 2026 training camp in West Virginia