Education

The Shortage in School Bus Drivers is Getting Worse

After the first day of school in Louisville, Ky., Patrick Lester could not find his 6-year-old daughter, Adara.

After he waited for 40 minutes at the bus stop, a phone call to the school revealed that she had been put on another bus, Mr. Lester said. But school staff members could not confirm whether she had been dropped off, nor could they reach the driver.

His partner, Heather Gray, left work and drove around the neighborhood, looking for Adara. Finally, she said, she saw a bus driving away from a street corner, and “it’s my daughter standing there.”

“We just moved here — she doesn’t know the neighborhood,” Ms. Gray explained. “And the bus driver had kicked her off and told her to walk home.”

A bus driver shortage that has plagued the country’s school districts for years came to a head in Louisville. After that first chaotic day, the city’s school system, Jefferson County Public Schools, which serves about 100,000 students, abruptly halted classes until at least Friday for elementary and middle school students, and Monday for high school students.

Marty Pollio, the district superintendent, said at a news conference on Monday the district will work to provide bus drivers everything they need for success, including increasing wages.

“We will continue to have more and more problems throughout this nation unless we address our significant bus driver issue,” he said.

While the situation in Louisville seemed extreme, many school districts have been contending with a shortage of bus drivers, driven by low pay,inconvenient hours and lingering effects of the pandemic.

In the Hillsborough County Public Schools district, which includes Tampa, Fla., there are still 203 bus driver vacancies even though school has already begun, with delays on the first two days of school last week, said Tanya Arja, chief of communications for the district.

In Charlottesville, Va., Albemarle County Public Schools notified the families of 1,000 children — total enrollment is 14,000 — that there was not a driver for their route, but school would go on as scheduled. .

Normally, there are up to 6,000 students who are transported a day, but this year the district received requests for 10,000, said Phil Giaramita, public affairs and strategic communications officer for Albemarle Public Schools.

And in Chicago, the school district is battling its driver shortage by offering free Ventra cards — which are used for the city’s public transit —- for qualifying students and one companion. About half of the district’s bus driver positions are vacant.

The search for bus drivers has been frustrating. The Stillwater Public Schools in central Oklahoma still have five full-time positions open, said Barry Fuxa, the district’s public relations and communications coordinator.

Like many districts, low pay and odd hours are the biggest issues. Starting pay last year for Stillwater bus drivers was $12.38 an hour, with six-hour days and morning and afternoon shifts that did not allow enough time for another job.

This year, Mr. Fuxa said, the district raised the salary for its bus drivers to $16.57 an hour. But without an advertising budget for the open positions, it has been difficult to spread the word, especially when competing with nearby school districts.

“You’re kind of tapping into a dry well at a certain point, “ Mr. Fuxa said. “There’s only so much you can do.”

Tomás Fret, president of the Local 1181 chapter of the Amalgamated Transit Union, which covers the New York metro region, said that low wages have been drawbacks, but also that the job has become more difficult, noting that there have been more confrontations with parents and students.

Mr. Fret, who started driving school buses in 1996, said, “When I started the job, workers were able to send their kids to college.”

Erica Groshen, a senior economics adviser at Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, said raising pay is the most straightforward way to find more bus drivers, but schools may need to turn to creative solutions.

“Employers want to improve retention,” she said. “Offering a way for the workers to have some voice and interviewing workers as they exit can be a very important way for them to figure out solutions.”

Public school officials at Jefferson County were trying their own creative solution — which helped lead to the opening day fiasco. They had hired AlphaRoute, a Boston-area engineering firm that specializes in routing software, to design new routes for the school year.

The goal, the district said, was to adjust for fewer drivers, but that resulted in longer routes.

“We recognize that the situation was extremely regrettable and likely caused by the significant changes to bus routing which were made necessary by the district’s severe driver shortage,” AlphaRoute said.

The district said it was working to overhaul its routes. As of now, there have not been discussions of changing its contract with AlphaRoute, which they paid $265,000 to design this year’s routes. The district has worked with the company since 2021.

Until school starts again, families must find child care. Mr. Lester said a grandmother has helped watch his children. At home, the children have been kept busy with activity sheets and reading to make sure they were prepared for when classes start.

Starr Martin, another parent in Jefferson County, said she was nervous last week while trying to locate her 9-year-old son, who had been put on the wrong bus.

Ms. Martin said the school board had not thought these changes through.

“There’s going to be hiccups on the first day,” she said, “but I think somebody needs to be held accountable for what happened.”

Education

Video: Protesters Scuffle With Police During Pomona College Commencement

new video loaded: Protesters Scuffle With Police During Pomona College Commencement

transcript

transcript

Protesters Scuffle With Police During Pomona College Commencement

Pro-Palestinian demonstrators tried to block access to Pomona College’s graduation ceremony on Sunday.

-

[chanting in call and response] Not another nickel, not another dime. No more money for Israel’s crime. Resistance is justified when people are occupied.

Recent episodes in U.S.

Education

Video: Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

new video loaded: Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

transcript

transcript

Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

Police officers arrested 33 pro-Palestinian protesters and cleared a tent encampment on the campus of George Washingon University.

-

“The Metropolitan Police Department. If you are currently on George Washington University property, you are in violation of D.C. Code 22-3302, unlawful entry on property.” “Back up, dude, back up. You’re going to get locked up tonight — back up.” “Free, free Palestine.” “What the [expletive] are you doing?” [expletives] “I can’t stop — [expletives].”

Recent episodes in Israel-Hamas War

Education

How Counterprotesters at U.C.L.A. Provoked Violence, Unchecked for Hours

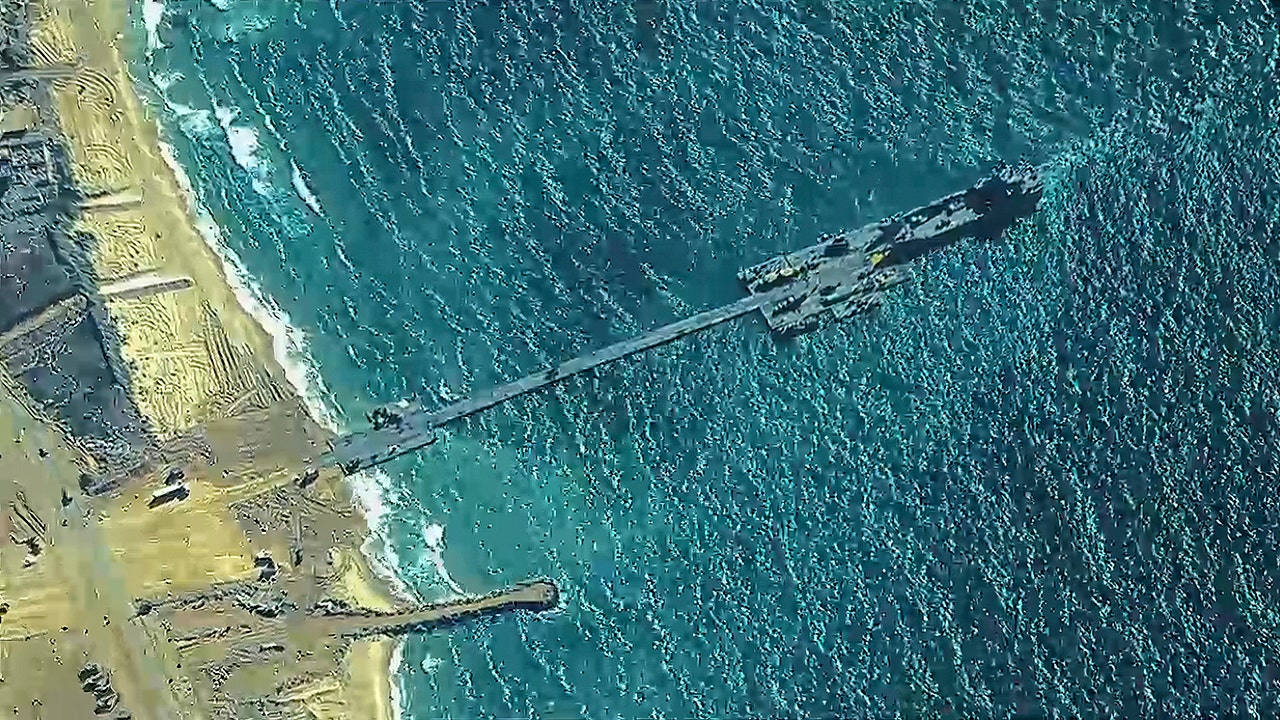

A satellite image of the UCLA campus.

On Tuesday night, violence erupted at an encampment that pro-Palestinian protesters had set up on April 25.

The image is annotated to show the extent of the pro-Palestinian encampment, which takes up the width of the plaza between Powell Library and Royce Hall.

The clashes began after counterprotesters tried to dismantle the encampment’s barricade. Pro-Palestinian protesters rushed to rebuild it, and violence ensued.

Arrows denote pro-Israeli counterprotesters moving towards the barricade at the edge of the encampment. Arrows show pro-Palestinian counterprotesters moving up against the same barricade.

Police arrived hours later, but they did not intervene immediately.

An arrow denotes police arriving from the same direction as the counterprotesters and moving towards the barricade.

A New York Times examination of more than 100 videos from clashes at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that violence ebbed and flowed for nearly five hours, mostly with little or no police intervention. The violence had been instigated by dozens of people who are seen in videos counterprotesting the encampment.

The videos showed counterprotesters attacking students in the pro-Palestinian encampment for several hours, including beating them with sticks, using chemical sprays and launching fireworks as weapons. As of Friday, no arrests had been made in connection with the attack.

To build a timeline of the events that night, The Times analyzed two livestreams, along with social media videos captured by journalists and witnesses.

The melee began when a group of counterprotesters started tearing away metal barriers that had been in place to cordon off pro-Palestinian protesters. Hours earlier, U.C.L.A. officials had declared the encampment illegal.

Security personnel hired by the university are seen in yellow vests standing to the side throughout the incident. A university spokesperson declined to comment on the security staff’s response.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

It is not clear how the counterprotest was organized or what allegiances people committing the violence had. The videos show many of the counterprotesters were wearing pro-Israel slogans on their clothing. Some counterprotesters blared music, including Israel’s national anthem, a Hebrew children’s song and “Harbu Darbu,” an Israeli song about the Israel Defense Forces’ campaign in Gaza.

As counterprotesters tossed away metal barricades, one of them was seen trying to strike a person near the encampment, and another threw a piece of wood into it — some of the first signs of violence.

Attacks on the encampment continued for nearly three hours before police arrived.

Counterprotesters shot fireworks toward the encampment at least six times, according to videos analyzed by The Times. One of them went off inside, causing protesters to scream. Another exploded at the edge of the encampment. One was thrown in the direction of a group of protesters who were carrying an injured person out of the encampment.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

Some counterprotesters sprayed chemicals both into the encampment and directly at people’s faces.

Sean Beckner-Carmitchel via Reuters

At times, counterprotesters swarmed individuals — sometimes a group descended on a single person. They could be seen punching, kicking and attacking people with makeshift weapons, including sticks, traffic cones and wooden boards.

StringersHub via Associated Press, Sergio Olmos/Calmatters

In one video, protesters sheltering inside the encampment can be heard yelling, “Do not engage! Hold the line!”

In some instances, protesters in the encampment are seen fighting back, using chemical spray on counterprotesters trying to tear down barricades or swiping at them with sticks.

Except for a brief attempt to capture a loudspeaker used by counterprotesters, and water bottles being tossed out of the encampment, none of the videos analyzed by The Times show any clear instance of encampment protesters initiating confrontations with counterprotesters beyond defending the barricades.

Shortly before 1 a.m. — more than two hours after the violence erupted — a spokesperson with the mayor’s office posted a statement that said U.C.L.A officials had called the Los Angeles Police Department for help and they were responding “immediately.”

Officers from a separate law enforcement agency — the California Highway Patrol — began assembling nearby, at about 1:45 a.m. Riot police with the L.A.P.D. joined them a few minutes later. Counterprotesters applauded their arrival, chanting “U.S.A., U.S.A., U.S.A.!”

Just four minutes after the officers arrived, counterprotesters attacked a man standing dozens of feet from the officers.

Twenty minutes after police arrive, a video shows a counterprotester spraying a chemical toward the encampment during a scuffle over a metal barricade. Another counterprotester can be seen punching someone in the head near the encampment after swinging a plank at barricades.

Fifteen minutes later, while those in the encampment chanted “Free, free Palestine,” counterprotesters organized a rush toward the barricades. During the rush, a counterprotester pulls away a metal barricade from a woman, yelling “You stand no chance, old lady.”

Throughout the intermittent violence, officers were captured on video standing about 300 feet away from the area for roughly an hour, without stepping in.

It was not until 2:42 a.m. that officers began to move toward the encampment, after which counterprotesters dispersed and the night’s violence between the two camps mostly subsided.

The L.A.P.D. and the California Highway Patrol did not answer questions from The Times about their responses on Tuesday night, deferring to U.C.L.A.

While declining to answer specific questions, a university spokesperson provided a statement to The Times from Mary Osako, U.C.L.A.’s vice chancellor of strategic communications: “We are carefully examining our security processes from that night and are grateful to U.C. President Michael Drake for also calling for an investigation. We are grateful that the fire department and medical personnel were on the scene that night.”

L.A.P.D. officers were seen putting on protective gear and walking toward the barricade around 2:50 a.m. They stood in between the encampment and the counterprotest group, and the counterprotesters began dispersing.

While police continued to stand outside the encampment, a video filmed at 3:32 a.m. shows a man who was walking away from the scene being attacked by a counterprotester, then dragged and pummeled by others. An editor at the U.C.L.A. student newspaper, the Daily Bruin, told The Times the man was a journalist at the paper, and that they were walking with other student journalists who had been covering the violence. The editor said she had also been punched and sprayed in the eyes with a chemical.

On Wednesday, U.C.L.A.’s chancellor, Gene Block, issued a statement calling the actions by “instigators” who attacked the encampment unacceptable. A spokesperson for California Gov. Gavin Newsom criticized campus law enforcement’s delayed response and said it demands answers.

Los Angeles Jewish and Muslim organizations also condemned the attacks. Hussam Ayloush, the director of the Greater Los Angeles Area office of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, called on the California attorney general to investigate the lack of police response. The Jewish Federation Los Angeles blamed U.C.L.A. officials for creating an unsafe environment over months and said the officials had “been systemically slow to respond when law enforcement is desperately needed.”

Fifteen people were reportedly injured in the attack, according to a letter sent by the president of the University of California system to the board of regents.

The night after the attack began, law enforcement warned pro-Palestinian demonstrators to leave the encampment or be arrested. By early Thursday morning, police had dismantled the encampment and arrested more than 200 people from the encampment.

-

Politics1 week ago

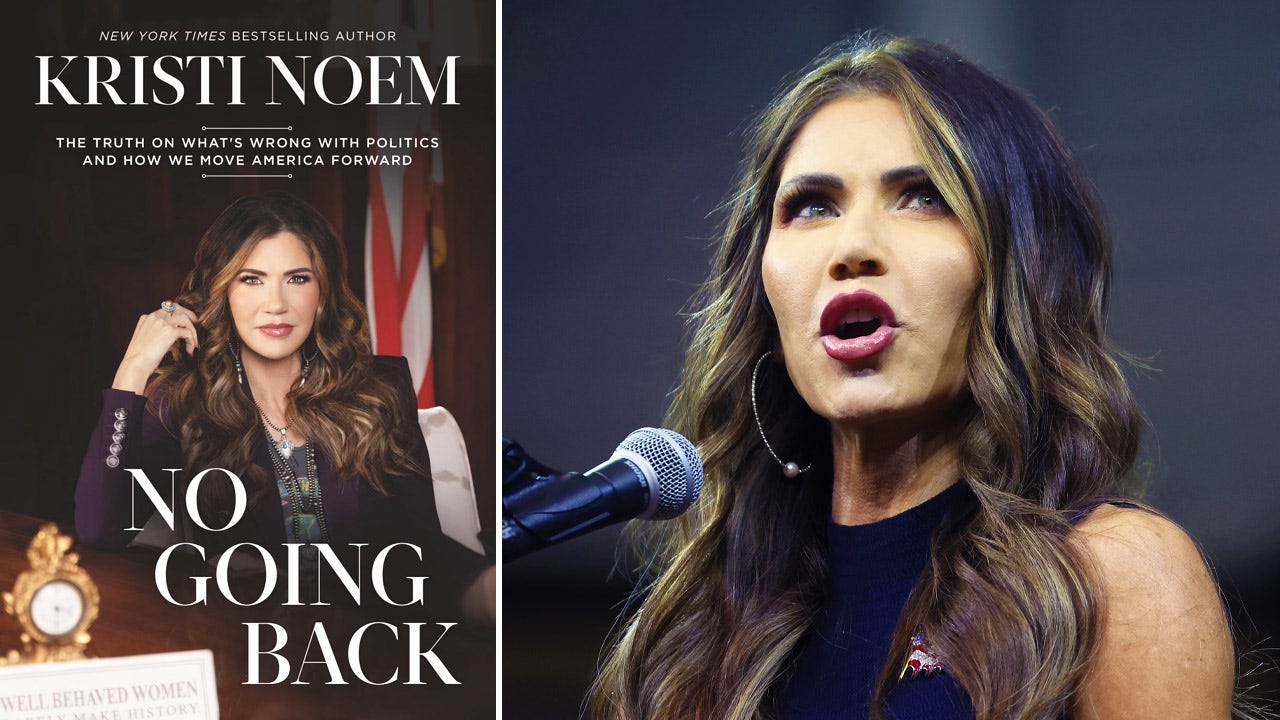

Politics1 week ago'You need to stop': Gov. Noem lashes out during heated interview over book anecdote about killing dog

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoMan, 75, confesses to killing wife in hospital because he couldn’t afford her care, court documents say

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRFK Jr said a worm ate part of his brain and died in his head

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPentagon chief confirms US pause on weapons shipment to Israel

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHere's what GOP rebels want from Johnson amid threats to oust him from speakership

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPro-Palestine protests: How some universities reached deals with students

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoConvicted MEP's expense claims must be published: EU court

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCalifornia Gov Gavin Newsom roasted over video promoting state's ‘record’ tourism: ‘Smoke and mirrors’

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24805888/STK160_X_Twitter_006.jpg)