Education

An Ambitious Antiracism Center Scales Back Amid Allegations of Poor Management

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in May 2020, protests, looting, and anger were boiling up in the streets of Boston, a city that has played host to both abolitionists and vicious race riots. At Boston University, Black students demanded action to address campus racism.

The university had a dramatic response. It announced a few days later that it had recruited Ibram X. Kendi, the celebrity professor who had spawned a movement through his book, “How to Be an Antiracist.”

The plans were ambitious. Dr. Kendi would head up a new Center for Antiracist Research. The university would develop undergraduate and graduate degrees in antiracism. Within months, millions had poured in for a center whose mission, Dr. Kendi said, would be to “solve seemingly intractable problems of racial inequity and injustice.”

Now, a mere three years later, the center is being downsized. More than half of its 36 employees were abruptly told last week they were being laid off. The center’s budget is also being trimmed in half. The planned degree programs have not come to fruition. And the center’s news site called “The Emancipator” is no longer a partnership with The Boston Globe.

The reorganization is partly a sign of the times. Enthusiasm for funding racial justice causes has diminished as Mr. Floyd’s murder has faded out of the media spotlight and conservatives direct their ire toward efforts to diversify companies and institutions and to teach race in schools.

But the center’s struggles come amid deeper concerns about its management and focus, and questions about whether Dr. Kendi — whose fame has brought him new projects from an ESPN series to children’s books about racist ideas in America — was providing the leadership the newly created institute needed. Until the university established the center, the 41-year-old Dr. Kendi had never run an organization anywhere near its size.

On Wednesday, Boston University announced it was conducting an inquiry into complaints from staff members, which include questions about the center’s management culture and the faculty and staff’s experience with it, as well as its grant management practices.

Dr. Kendi said in an interview that he made “the painful decision” to reduce the program’s size and mission in an effort to guarantee its future, even though the center is currently financially healthy. The university said Friday that the center has raised nearly $55 million and its endowment contains about $30 million, with an additional $17.5 million held in reserves.

The bulk of the donations came from pledges made during the first year, and the university reported $5.4 million in cash and pledge payments in the most recent fiscal year.

Despite the university’s statement that it would look into the center’s management, the university’s interim president, Kenneth Freeman, on Thursday voiced strong support for Dr. Kendi, saying the professor had come to the university early in the summer with his idea for the reorganized center.

“We continue to have confidence in Dr. Kendi’s vision and we support it,” Mr. Freeman said.

But several former staff and faculty members, expressing anger and bitterness, said the cause of the center’s problems were unrealistic expectations fueled by the rapid infusion of money, initial excitement, and pressure to produce too much, too fast, even as there were hiring delays due to the pandemic. Others blamed Dr. Kendi, himself, for what they described as an imperious leadership style. And they questioned both the center’s stewardship of grants and its productivity.

“Commensurate to the amount of cash and donations taken in, the outputs were minuscule,” said Saida U. Grundy, a Boston University sociology professor and feminist scholar who was once affiliated with the center.

The turmoil comes as Dr. Kendi’s work continues to face attacks from the outside. In his books he contends that there’s no middle ground on race — everyone is either racist or actively antiracist. And he suggests that all disparities in Black outcomes and achievements are because of racism. That has ignited criticism from conservatives, ranging from some Black intellectuals to Republican-led state governments, which have banned his books from their classrooms and libraries.

Dr. Kendi acknowledged that the fund-raising environment for the center “isn’t like it was in 2020 when it was the popular thing to do.” But he added that the center still has committed funders.

And calling the changes in the center a “major pivot,” he said, “I really had to ensure that 20 years from now, 50 years from now, 100 years from now, the center will be around.”

The center’s new model, Dr. Kendi said, will be the first of its kind, a fellowship program for antiracist intellectuals who will be in residence at the university for nine months, participating in public events while conducting their own research.

Dr. Kendi was a professor at the University of Florida in 2016 when his book, “Stamped From the Beginning,” a history of racist thought in America, was a surprise National Book Award winner. A subsequent book, “How to Be an Antiracist,” became a best seller in 2019.

As much a public influencer as a scholar, Dr. Kendi became a flashpoint in the culture wars with his idea that to be an antiracist, one must first acknowledge being a racist.

Dr. Kendi came to Boston at both an opportune time — in the middle of the 2020 racial reckoning — and a challenging one — the early months of the Covid pandemic.

Acknowledging a difficult start-up in the midst of the pandemic — along with some conflicts among staff members who had strong and divergent ideas for the center’s focus — Dr. Kendi said he was proud of the center’s work so far.

The center says its key initiatives and accomplishments include The Emancipator; its National Antiracist Book Festivals; policy conferences on bigotry and racial classifications; 10 amicus briefs filed in racial-justice lawsuits and an antiracist technology initiative.

Even as the cutbacks were announced, the center was preparing this weekend for a meeting of 60 journalists who cover race. From the outside, though, the center’s operations appeared to be struggling. Portions of its website had been taken down.

And the center’s work, perhaps inevitably, has become synonymous with the celebrity and notoriety of Dr. Kendi.

Even as he was overseeing the center, along with a staff of administrators and academics that at one point totaled about 43 people, his business franchise has continued to grow. And some worry he has taken on far more work than can be done while running the center.

In publishing, he has spun off children’s books based on his theme. “Antiracist Baby” is geared to young children, and “How to Be a Young Antiracist,” is aimed at 12- to 17-year-olds. He has also published a guide for parents, “How to Raise an Antiracist.” His other children’s books include adaptations of work by Zora Neale Hurston. He is a contributor to The Atlantic.

In broadcasting, he has hosted his own podcast while also appearing as a commentator on CBS and cable television. He has formed his own production company, Maroon Visions, recently involved in an ESPN+ series exploring racism in sports, “Skin in the Game, which premiered on Wednesday.

He teaches an undergraduate course at B.U. on antiracism and frequently speaks at universities and conferences across the country, sometimes drawing controversy.

Dr. Grundy said that despite Dr. Kendi’s busy outside schedule, “Ibram didn’t want to give up any power.”

And in academia, where popular success can often generate pushback, his work has been criticized by some scholars who question its academic rigor and also by some on the left who worry that it has been influenced, to some degree, by the big donors who have helped create the center.

Spencer Piston, a professor of political science who worked in the center’s policy office, criticized the university’s original decision to bring in Dr. Kendi, which he viewed as a substitute for addressing more specific student complaints — including criticism of the campus police force and the lack of faculty diversity.

“It’s a failure of a particular type of corporatist university response to those same struggles,” Dr. Piston said.

Within the first year following Dr. Kendi’s hiring, more than $43 million in grant and gift pledges had flowed in, including an anonymous $25 million gift and $10 million from Jack Dorsey, co-founder of Twitter.

Money was streaming in, but the new staff came on board slowly as the fledgling operation attempted to work remotely.

More than one former employee complained about how grants were handled, with their allegations including conflicts of interest or misleading promises to donors. The center’s staff also became engaged in a political struggle, of sorts — a debate over what antiracism should look like.

Dr. Piston, for example, questioned whether the center hewed to donor interests at the expense of interacting with community-based groups. He cited the participation of the chief executive of Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which is developing a treatment for sickle cell anemia, in a center conference on public health. The company’s foundation is a donor.

Phillipe Copeland, a professor in the university’s Department of Social Work who also served at the center until he resigned in June, said some faculty had chafed at Dr. Kendi, making Dr. Copeland’s work — developing the graduate program in antiracism studies — difficult.

”There were some bad feelings about interactions people had with Dr. Kendi that made some people not want to participate and support what we were doing,” Dr. Copeland said. “I heard that a lot.”

In an interview, Dr. Kendi said that critics were using the situation “to settle old scores and demonstrate that I’m a problem or that antiracism is a problem.”

“Unfortunately we live in such a polarized, spiteful sort of reactionary moment,” he said.

Colbi Edmonds contributed reporting.

Education

How Counterprotesters at U.C.L.A. Provoked Violence, Unchecked for Hours

A satellite image of the UCLA campus.

On Tuesday night, violence erupted at an encampment that pro-Palestinian protesters had set up on April 25.

The image is annotated to show the extent of the pro-Palestinian encampment, which takes up the width of the plaza between Powell Library and Royce Hall.

The clashes began after counterprotesters tried to dismantle the encampment’s barricade. Pro-Palestinian protesters rushed to rebuild it, and violence ensued.

Arrows denote pro-Israeli counterprotesters moving towards the barricade at the edge of the encampment. Arrows show pro-Palestinian counterprotesters moving up against the same barricade.

Police arrived hours later, but they did not intervene immediately.

An arrow denotes police arriving from the same direction as the counterprotesters and moving towards the barricade.

A New York Times examination of more than 100 videos from clashes at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that violence ebbed and flowed for nearly five hours, mostly with little or no police intervention. The violence had been instigated by dozens of people who are seen in videos counterprotesting the encampment.

The videos showed counterprotesters attacking students in the pro-Palestinian encampment for several hours, including beating them with sticks, using chemical sprays and launching fireworks as weapons. As of Friday, no arrests had been made in connection with the attack.

To build a timeline of the events that night, The Times analyzed two livestreams, along with social media videos captured by journalists and witnesses.

The melee began when a group of counterprotesters started tearing away metal barriers that had been in place to cordon off pro-Palestinian protesters. Hours earlier, U.C.L.A. officials had declared the encampment illegal.

Security personnel hired by the university are seen in yellow vests standing to the side throughout the incident. A university spokesperson declined to comment on the security staff’s response.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

It is not clear how the counterprotest was organized or what allegiances people committing the violence had. The videos show many of the counterprotesters were wearing pro-Israel slogans on their clothing. Some counterprotesters blared music, including Israel’s national anthem, a Hebrew children’s song and “Harbu Darbu,” an Israeli song about the Israel Defense Forces’ campaign in Gaza.

As counterprotesters tossed away metal barricades, one of them was seen trying to strike a person near the encampment, and another threw a piece of wood into it — some of the first signs of violence.

Attacks on the encampment continued for nearly three hours before police arrived.

Counterprotesters shot fireworks toward the encampment at least six times, according to videos analyzed by The Times. One of them went off inside, causing protesters to scream. Another exploded at the edge of the encampment. One was thrown in the direction of a group of protesters who were carrying an injured person out of the encampment.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

Some counterprotesters sprayed chemicals both into the encampment and directly at people’s faces.

Sean Beckner-Carmitchel via Reuters

At times, counterprotesters swarmed individuals — sometimes a group descended on a single person. They could be seen punching, kicking and attacking people with makeshift weapons, including sticks, traffic cones and wooden boards.

StringersHub via Associated Press, Sergio Olmos/Calmatters

In one video, protesters sheltering inside the encampment can be heard yelling, “Do not engage! Hold the line!”

In some instances, protesters in the encampment are seen fighting back, using chemical spray on counterprotesters trying to tear down barricades or swiping at them with sticks.

Except for a brief attempt to capture a loudspeaker used by counterprotesters, and water bottles being tossed out of the encampment, none of the videos analyzed by The Times show any clear instance of encampment protesters initiating confrontations with counterprotesters beyond defending the barricades.

Shortly before 1 a.m. — more than two hours after the violence erupted — a spokesperson with the mayor’s office posted a statement that said U.C.L.A officials had called the Los Angeles Police Department for help and they were responding “immediately.”

Officers from a separate law enforcement agency — the California Highway Patrol — began assembling nearby, at about 1:45 a.m. Riot police with the L.A.P.D. joined them a few minutes later. Counterprotesters applauded their arrival, chanting “U.S.A., U.S.A., U.S.A.!”

Just four minutes after the officers arrived, counterprotesters attacked a man standing dozens of feet from the officers.

Twenty minutes after police arrive, a video shows a counterprotester spraying a chemical toward the encampment during a scuffle over a metal barricade. Another counterprotester can be seen punching someone in the head near the encampment after swinging a plank at barricades.

Fifteen minutes later, while those in the encampment chanted “Free, free Palestine,” counterprotesters organized a rush toward the barricades. During the rush, a counterprotester pulls away a metal barricade from a woman, yelling “You stand no chance, old lady.”

Throughout the intermittent violence, officers were captured on video standing about 300 feet away from the area for roughly an hour, without stepping in.

It was not until 2:42 a.m. that officers began to move toward the encampment, after which counterprotesters dispersed and the night’s violence between the two camps mostly subsided.

The L.A.P.D. and the California Highway Patrol did not answer questions from The Times about their responses on Tuesday night, deferring to U.C.L.A.

While declining to answer specific questions, a university spokesperson provided a statement to The Times from Mary Osako, U.C.L.A.’s vice chancellor of strategic communications: “We are carefully examining our security processes from that night and are grateful to U.C. President Michael Drake for also calling for an investigation. We are grateful that the fire department and medical personnel were on the scene that night.”

L.A.P.D. officers were seen putting on protective gear and walking toward the barricade around 2:50 a.m. They stood in between the encampment and the counterprotest group, and the counterprotesters began dispersing.

While police continued to stand outside the encampment, a video filmed at 3:32 a.m. shows a man who was walking away from the scene being attacked by a counterprotester, then dragged and pummeled by others. An editor at the U.C.L.A. student newspaper, the Daily Bruin, told The Times the man was a journalist at the paper, and that they were walking with other student journalists who had been covering the violence. The editor said she had also been punched and sprayed in the eyes with a chemical.

On Wednesday, U.C.L.A.’s chancellor, Gene Block, issued a statement calling the actions by “instigators” who attacked the encampment unacceptable. A spokesperson for California Gov. Gavin Newsom criticized campus law enforcement’s delayed response and said it demands answers.

Los Angeles Jewish and Muslim organizations also condemned the attacks. Hussam Ayloush, the director of the Greater Los Angeles Area office of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, called on the California attorney general to investigate the lack of police response. The Jewish Federation Los Angeles blamed U.C.L.A. officials for creating an unsafe environment over months and said the officials had “been systemically slow to respond when law enforcement is desperately needed.”

Fifteen people were reportedly injured in the attack, according to a letter sent by the president of the University of California system to the board of regents.

The night after the attack began, law enforcement warned pro-Palestinian demonstrators to leave the encampment or be arrested. By early Thursday morning, police had dismantled the encampment and arrested more than 200 people from the encampment.

Education

Video: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

new video loaded: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

transcript

transcript

President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

President Biden defended the right of demonstrators to protest peacefully, but condemned the “chaos” that has prevailed at many colleges nationwide.

-

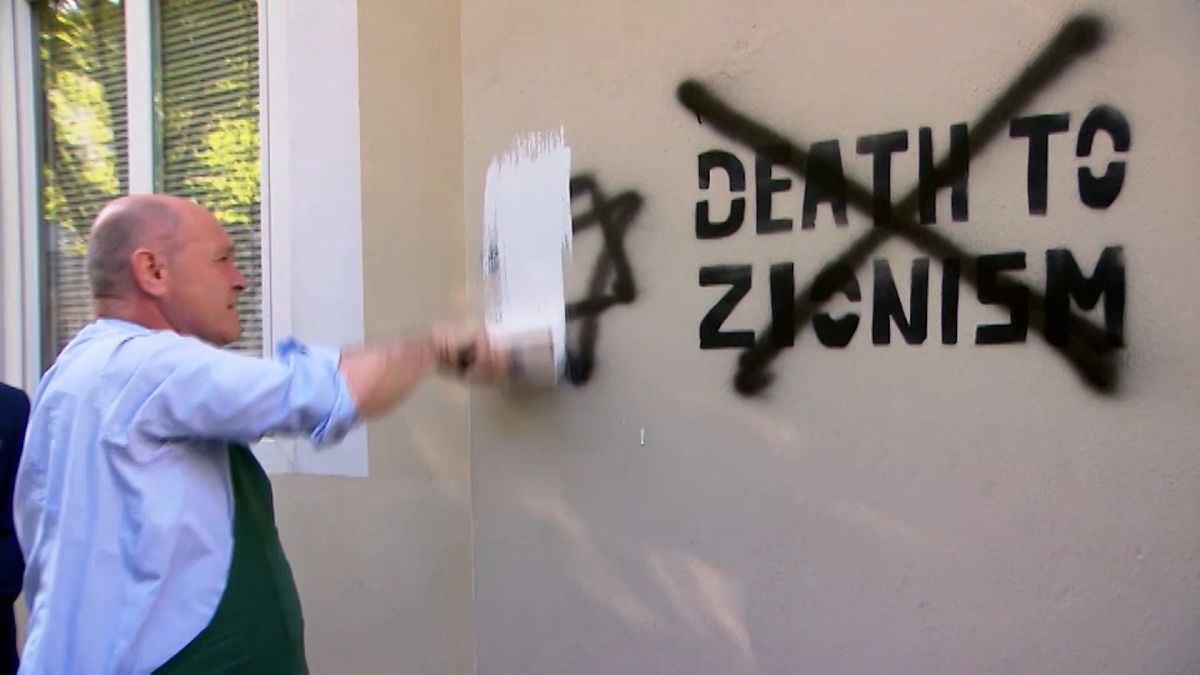

Violent protest is not protected. Peaceful protest is. It’s against the law when violence occurs. Destroying property is not a peaceful protest. It’s against the law. Vandalism, trespassing, breaking windows, shutting down campuses, forcing the cancellation of classes and graduations — none of this is a peaceful protest. Threatening people, intimidating people, instilling fear in people is not peaceful protest. It’s against the law. Dissent is essential to democracy, but dissent must never lead to disorder or to denying the rights of others, so students can finish the semester and their college education. There’s the right to protest, but not the right to cause chaos. People have the right to get an education, the right to get a degree, the right to walk across the campus safely without fear of being attacked. But let’s be clear about this as well. There should be no place on any campus — no place in America — for antisemitism or threats of violence against Jewish students. There is no place for hate speech or violence of any kind, whether it’s antisemitism, Islamophobia or discrimination against Arab Americans or Palestinian Americans. It’s simply wrong. There’s no place for racism in America.

Recent episodes in Politics

Education

Where Protesters on U.S. Campuses Have Been Arrested or Detained

Police officers and university administrators have clashed with pro-Palestinian protesters on a growing number of college campuses in recent weeks, arresting students, removing encampments and threatening academic consequences. More than 2,000 people have been arrested or detained on campuses across the country.

Ala.

Alaska Ariz.

Ark.

Calif.

Colo.

Del. Fla.

Ga.

Hawaii

Idaho

Ill. Ind.

Iowa

Kan.

Ky.

La. Maine

Md.

Mass.

Mich.

Minn. Miss.

Mo.

Mont.

Neb.

Nev. N.H.

N.J.

N.M.

N.Y.

N.C. N.D.

Ohio

Okla.

Ore.

Pa. S.C.

S.D.

Tenn.

Texas

Utah Vt.

Va.

Wash.

W.Va.

Wis. Wyo.

Ala. Alaska

Ariz.

Ark.

Calif.

Colo. Del.

Fla.

Ga.

Hawaii

Idaho Ill.

Ind.

Iowa

Kan.

Ky. La.

Maine

Md.

Mass.

Mich. Minn.

Miss.

Mo.

Mont.

Neb. Nev.

N.H.

N.J.

N.M.

N.Y. N.C.

N.D.

Ohio

Okla.

Ore. Pa.

S.C.

S.D.

Tenn.

Texas Utah

Vt.

Va.

Wash.

W.Va. Wis.

Wyo.

Campus protests where arrests and detainments have taken place since April 18

The fresh wave of student activism against the war in Gaza was sparked by the arrests of at least 108 protesters at Columbia University on April 18, after administrators appeared before Congress and promised a crackdown. Since then, tensions between protesters, universities and the police have risen, prompting law enforcement to take action in some of America’s largest cities.

Arizona State University

Tempe, Ariz.

72

Cal Poly Humboldt

Arcata, Calif.

60

Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

20

City College of New York

New York, N.Y.

173

Columbia University

New York, N.Y.

217

Dartmouth College

Hanover, N.H.

90

Emerson College

Boston, Mass.

118

Emory University

Atlanta, Ga.

28

Florida State University

Tallahassee, Fla.

5

Fordham University

New York, N.Y.

15

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoGOP Rep. Bill Posey won't seek re-election, endorses former Florida Senate President as replacement

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussian forces gained partial control of Donetsk's Ocheretyne town

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Challengers Movie Review

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoZelenskyy warns of Russian nuclear risks on Chernobyl anniversary

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Republicans brace for spring legislative sprint with one less GOP vote

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAt least four dead in US after dozens of tornadoes rip through Oklahoma

-

Politics1 week ago

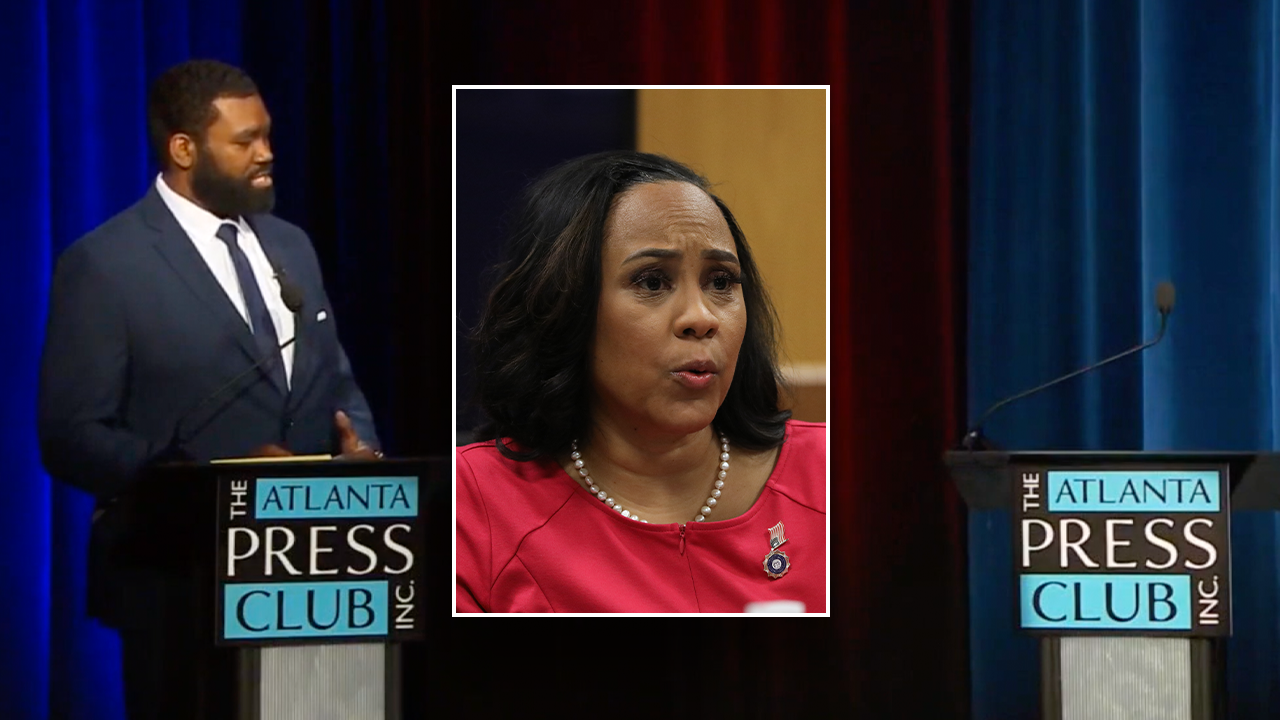

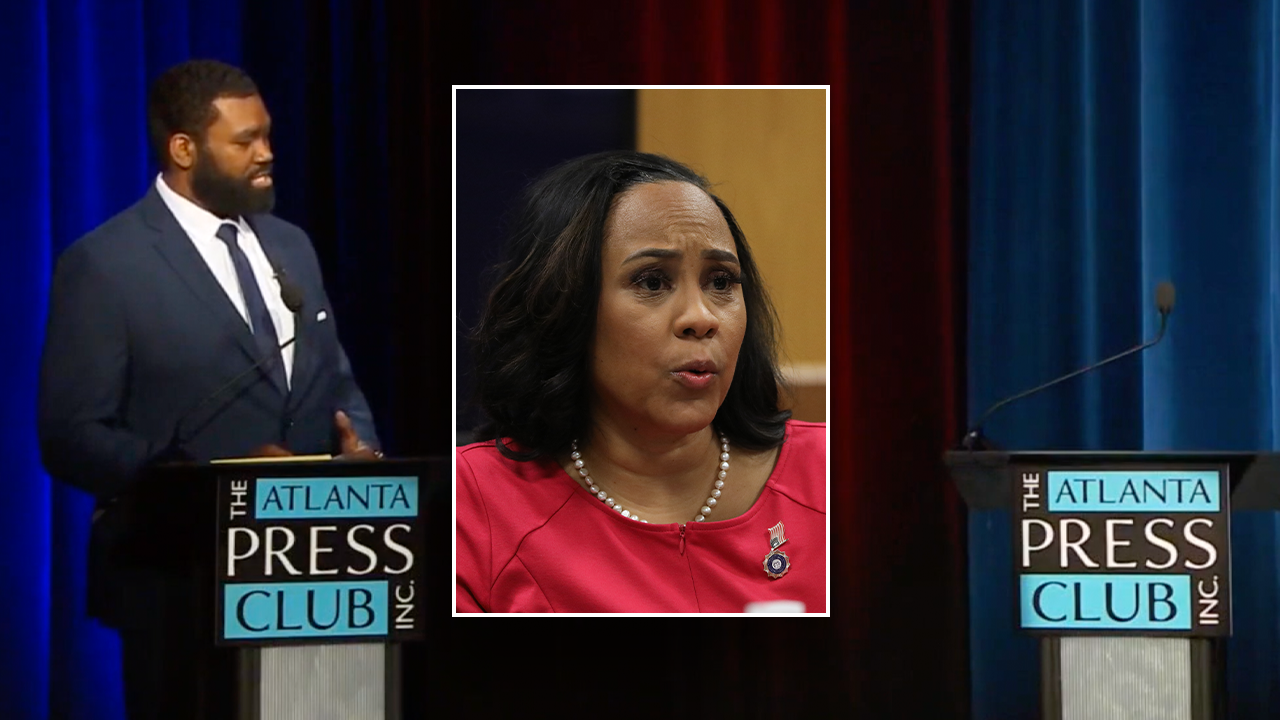

Politics1 week agoAnti-Trump DA's no-show at debate leaves challenger facing off against empty podium

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWashington chooses its wars; Ukraine and Israel have made the cut despite opposition on right and left