Business

Religious Leaders Experiment with A.I. in Sermons

To members of his synagogue, the voice that played over the speakers of Congregation Emanu El in Houston sounded just like Rabbi Josh Fixler’s.

In the same steady rhythm his congregation had grown used to, the voice delivered a sermon about what it meant to be a neighbor in the age of artificial intelligence. Then, Rabbi Fixler took to the bimah himself.

“The audio you heard a moment ago may have sounded like my words,” he said. “But they weren’t.”

The recording was created by what Rabbi Fixler called “Rabbi Bot,” an A.I. chatbot trained on his old sermons. The chatbot, created with the help of a data scientist, wrote the sermon, even delivering it in an A.I. version of his voice. During the rest of the service, Rabbi Fixler intermittently asked Rabbi Bot questions aloud, which it would promptly answer.

Rabbi Fixler is among a growing number of religious leaders experimenting with A.I. in their work, spurring an industry of faith-based tech companies that offer A.I. tools, from assistants that can do theological research to chatbots that can help write sermons.

For centuries, new technologies have changed the ways people worship, from the radio in the 1920s to television sets in the 1950s and the internet in the 1990s. Some proponents of A.I. in religious spaces have gone back even further, comparing A.I.’s potential — and fears of it — to the invention of the printing press in the 15th century.

Religious leaders have used A.I. to translate their livestreamed sermons into different languages in real time, blasting them out to international audiences. Others have compared chatbots trained on tens of thousands of pages of Scripture to a fleet of newly trained seminary students, able to pull excerpts about certain topics nearly instantaneously.

But the ethical questions around using generative A.I. for religious tasks have become more complicated as the technology has improved, religious leaders say. While most agree that using A.I. for tasks like research or marketing is acceptable, other uses for the technology, like sermon writing, are seen by some as a step too far.

Jay Cooper, a pastor in Austin, Texas, used OpenAI’s ChatGPT to generate an entire service for his church as an experiment in 2023. He marketed it using posters of robots, and the service drew in some curious new attendees — “gamer types,” Mr. Cooper said — who had never before been to his congregation.

The thematic prompt he gave ChatGPT to generate various parts of the service was: “How can we recognize truth in a world where A.I. blurs the truth?” ChatGPT came up with a welcome message, a sermon, a children’s program and even a four-verse song, which was the biggest hit of the bunch, Mr. Cooper said. The song went:

As algorithms spin webs of lies

We lift our gaze to the endless skies

Where Christ’s teachings illuminate our way

Dispelling falsehoods with the light of day

Mr. Cooper has not since used the technology to help write sermons, preferring to draw instead from his own experiences. But the presence of A.I. in faith-based spaces, he said, poses a larger question: Can God speak through A.I.?

“That’s a question a lot of Christians online do not like at all because it brings up some fear,” Mr. Cooper said. “It may be for good reason. But I think it’s a worthy question.”

The impact of A.I. on religion and ethics has been a touch point for Pope Francis on several occasions, though he has not directly addressed using A.I. to help write sermons.

Our humanity “enables us to look at things with God’s eyes, to see connections, situations, events and to uncover their real meaning,” the pope said in a message early last year. “Without this kind of wisdom, life becomes bland.”

He added, “Such wisdom cannot be sought from machines.”

Phil EuBank, a pastor at Menlo Church in Menlo Park, Calif., compared A.I. to a “bionic arm” that could supercharge his work. But when it comes to sermon writing, “there’s that Uncanny Valley territory,” he said, “where it may get you really close, but really close can be really weird.”

Rabbi Fixler agreed. He recalled being taken aback when Rabbi Bot asked him to include in his A.I. sermon, a one-time experiment, a line about itself.

“Just as the Torah instructs us to love our neighbors as ourselves,” Rabbi Bot said, “can we also extend this love and empathy to the A.I. entities we create?”

Rabbis have historically been early adopters of new technologies, especially for printed books in the 15th century. But the divinity of those books was in the spiritual relationship that their readers had with God, said Rabbi Oren Hayon, who is also a part of Congregation Emanu El.

To assist his research, Rabbi Hayon regularly uses a custom chatbot trained on 20 years of his own writings. But he has never used A.I. to write portions of sermons.

“Our job is not just to put pretty sentences together,” Rabbi Hayon said. “It’s to hopefully write something that’s lyrical and moving and articulate, but also responds to the uniquely human hungers and pains and losses that we’re aware of because we are in human communities with other people.” He added, “It can’t be automated.”

Kenny Jahng, a tech entrepreneur, believes that fears about ministers’ using generative A.I. are overblown, and that leaning into the technology may even be necessary to appeal to a new generation of young, tech-savvy churchgoers when church attendance across the country is in decline.

Mr. Jahng, the editor in chief of a faith- and tech-focused media company and founder of an A.I. education platform, has traveled the country in the last year to speak at conferences and promote faith-based A.I. products. He also runs a Facebook group for tech-curious church leaders with over 6,000 members.

“We are looking at data that the spiritually curious in Gen Alpha, Gen Z are much higher than boomers and Gen X-ers that have left the church since Covid,” Mr. Jahng said. “It’s this perfect storm.”

As of now, a majority of faith-based A.I. companies cater to Christians and Jews, but custom chatbots for Muslims and Buddhists exist as well.

Some churches have already started to subtly infuse their services and websites with A.I.

The chatbot on the website of the Father’s House, a church in Leesburg, Fla., for instance, appears to offer standard customer service. Among its recommended questions: “What time are your services?”

The next suggestion is more complex.

“Why are my prayers not answered?”

The chatbot was created by Pastors.ai, a start-up founded by Joe Suh, a tech entrepreneur and attendee of Mr. EuBank’s church in Silicon Valley.

After one of Mr. Suh’s longtime pastors left his church, he had the idea of uploading recordings of that pastor’s sermons to ChatGPT. Mr. Suh would then ask the chatbot intimate questions about his faith. He turned the concept into a business.

Mr. Suh’s chatbots are trained on archives of a church’s sermons and information from its website. But around 95 percent of the people who use the chatbots ask them questions about things like service times rather than probing deep into their spirituality, Mr. Suh said.

“I think that will eventually change, but for now, that concept might be a little bit ahead of its time,” he added.

Critics of A.I. use by religious leaders have pointed to the issue of hallucinations — times when chatbots make stuff up. While harmless in certain situations, faith-based A.I. tools that fabricate religious scripture present a serious problem. In Rabbi Bot’s sermon, for instance, the A.I. invented a quote from the Jewish philosopher Maimonides that would have passed as authentic to the casual listener.

For other religious leaders, the issue of A.I. is a simpler one: How can sermon writers hone their craft without doing it entirely themselves?

“I worry for pastors, in some ways, that it won’t help them stretch their sermon writing muscles, which is where I think so much of our great theology and great sermons come from, years and years of preaching,” said Thomas Costello, a pastor at New Hope Hawaii Kai in Honolulu.

On a recent afternoon at his synagogue, Rabbi Hayon recalled taking a picture of his bookshelf and asking his A.I. assistant which of the books he had not quoted in his recent sermons. Before A.I., he would have pulled down the titles themselves, taking the time to read through their indexes, carefully checking them against his own work.

“I was a little sad to miss that part of the process that is so fruitful and so joyful and rich and enlightening, that gives fuel to the life of the Spirit,” Rabbi Hayon said. “Using A.I. does get you to an answer quicker, but you’ve certainly lost something along the way.”

Business

Commentary: How Trump helped foreign markets outperform U.S. stocks during his first year in office

Trump has crowed about the gains in the U.S. stock market during his term, but in 2025 investors saw more opportunity in the rest of the world.

If you’re a stock market investor you might be feeling pretty good about how your portfolio of U.S. equities fared in the first year of President Trump’s term.

All the major market indices seemed to be firing on all cylinders, with the Standard & Poor’s 500 index gaining 17.9% through the full year.

But if you’re the type of investor who looks for things to regret, pay no attention to the rest of the world’s stock markets. That’s because overseas markets did better than the U.S. market in 2025 — a lot better. The MSCI World ex-USA index — that is, all the stock markets except the U.S. — gained more than 32% last year, nearly double the percentage gains of U.S. markets.

That’s a major departure from recent trends. Since 2013, the MSCI US index had bested the non-U.S. index every year except 2017 and 2022, sometimes by a wide margin — in 2024, for instance, the U.S. index gained 24.6%, while non-U.S. markets gained only 4.7%.

The Trump trade is dead. Long live the anti-Trump trade.

— Katie Martin, Financial Times

Broken down into individual country markets (also by MSCI indices), in 2025 the U.S. ranked 21st out of 23 developed markets, with only New Zealand and Denmark doing worse. Leading the pack were Austria and Spain, with 86% gains, but superior records were turned in by Finland, Ireland and Hong Kong, with gains of 50% or more; and the Netherlands, Norway, Britain and Japan, with gains of 40% or more.

Investment analysts cite several factors to explain this trend. Judging by traditional metrics such as price/earnings multiples, the U.S. markets have been much more expensive than those in the rest of the world. Indeed, they’re historically expensive. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index traded in 2025 at about 23 times expected corporate earnings; the historical average is 18 times earnings.

Investment managers also have become nervous about the concentration of market gains within the U.S. technology sector, especially in companies associated with artificial intelligence R&D. Fears that AI is an investment bubble that could take down the S&P’s highest fliers have investors looking elsewhere for returns.

But one factor recurs in almost all the market analyses tracking relative performance by U.S. and non-U.S. markets: Donald Trump.

Investors started 2025 with optimism about Trump’s influence on trading opportunities, given his apparent commitment to deregulation and his braggadocio about America’s dominant position in the world and his determination to preserve, even increase it.

That hasn’t been the case for months.

”The Trump trade is dead. Long live the anti-Trump trade,” Katie Martin of the Financial Times wrote this week. “Wherever you look in financial markets, you see signs that global investors are going out of their way to avoid Donald Trump’s America.”

Two Trump policy initiatives are commonly cited by wary investment experts. One, of course, is Trump’s on-and-off tariffs, which have left investors with little ability to assess international trade flows. The Supreme Court’s invalidation of most Trump tariffs and the bellicosity of his response, which included the immediate imposition of new 10% tariffs across the board and the threat to increase them to 15%, have done nothing to settle investors’ nerves.

Then there’s Trump’s driving down the value of the dollar through his agitation for lower interest rates, among other policies. For overseas investors, a weaker dollar makes U.S. assets more expensive relative to the outside world.

It would be one thing if trade flows and the dollar’s value reflected economic conditions that investors could themselves parse in creating a picture of investment opportunities. That’s not the case just now. “The current uncertainty is entirely man-made (largely by one orange-hued man in particular) but could well continue at least until the US mid-term elections in November,” Sam Burns of Mill Street Research wrote on Dec. 29.

Trump hasn’t been shy about trumpeting U.S. stock market gains as emblems of his policy wisdom. “The stock market has set 53 all-time record highs since the election,” he said in his State of the Union address Tuesday. “Think of that, one year, boosting pensions, 401(k)s and retirement accounts for the millions and the millions of Americans.”

Trump asserted: “Since I took office, the typical 401(k) balance is up by at least $30,000. That’s a lot of money. … Because the stock market has done so well, setting all those records, your 401(k)s are way up.”

Trump’s figure doesn’t conform to findings by retirement professionals such as the 401(k) overseers at Bank of America. They reported that the average account balance grew by only about $13,000 in 2025. I asked the White House for the source of Trump’s claim, but haven’t heard back.

Interpreting stock market returns as snapshots of the economy is a mug’s game. Despite that, at her recent appearance before a House committee, Atty. Gen. Pam Bondi tried to deflect questions about her handling of the Jeffrey Epstein records by crowing about it.

“The Dow is over 50,000 right now, she declared. “Americans’ 401(k)s and retirement savings are booming. That’s what we should be talking about.”

I predicted that the administration would use the Dow industrial average’s break above 50,000 to assert that “the overall economy is firing on all cylinders, thanks to his policies.” The Dow reached that mark on Feb. 6. But Feb. 11, the day of Bondi’s testimony, was the last day the index closed above 50,000. On Thursday, it closed at 49,499.50, or about 1.4% below its Feb. 10 peak close of 50,188.14.

To use a metric suggested by economist Justin Wolfers of the University of Michigan, if you invested $48,488 in the Dow on the day Trump took office last year, when the Dow closed at 48,448 points, you would have had $50,000 on Feb. 6. That’s a gain of about 3.2%. But if you had invested the same amount in the global stock market not including the U.S. (based on the MSCI World ex-USA index), on that same day you would have had nearly $60,000. That’s a gain of nearly 24%.

Broader market indices tell essentially the same story. From Jan. 17, 2025, the last day before Trump’s inauguration, through Thursday’s close, the MSCI US stock index gained a cumulative 16.3%. But the world index minus the U.S. gained nearly 42%.

The gulf between U.S. and non-U.S. performance has continued into the current year. The S&P 500 has gained about 0.74% this year through Wednesday, while the MSCI World ex-USA index has gained about 8.9%. That’s “the best start for a calendar year for global stocks relative to the S&P 500 going back to at least 1996,” Morningstar reports.

It wouldn’t be unusual for the discrepancy between the U.S. and global markets to shrink or even reverse itself over the course of this year.

That’s what happened in 2017, when overseas markets as tracked by MSCI beat the U.S. by more than three percentage points, and 2022, when global markets lost money but U.S. markets underperformed the rest of the world by more than five percentage points.

Economic conditions change, and often the stock markets march to their own drummers. The one thing less likely to change is that Trump is set to remain president until Jan. 20, 2029. Make your investment bets accordingly.

Business

How the S&P 500 Stock Index Became So Skewed to Tech and A.I.

Nvidia, the chipmaker that became the world’s most valuable public company two years ago, was alone worth more than $4.75 trillion as of Thursday morning. Its value, or market capitalization, is more than double the combined worth of all the companies in the energy sector, including oil giants like Exxon Mobil and Chevron.

The chipmaker’s market cap has swelled so much recently, it is now 20 percent greater than the sum of all of the companies in the materials, utilities and real estate sectors combined.

What unifies these giant tech companies is artificial intelligence. Nvidia makes the hardware that powers it; Microsoft, Apple and others have been making big bets on products that people can use in their everyday lives.

But as worries grow over lavish spending on A.I., as well as the technology’s potential to disrupt large swaths of the economy, the outsize influence that these companies exert over markets has raised alarms. They can mask underlying risks in other parts of the index. And if a handful of these giants falter, it could mean widespread damage to investors’ portfolios and retirement funds in ways that could ripple more broadly across the economy.

The dynamic has drawn comparisons to past crises, notably the dot-com bubble. Tech companies also made up a large share of the stock index then — though not as much as today, and many were not nearly as profitable, if they made money at all.

How the current moment compares with past pre-crisis moments

To understand how abnormal and worrisome this moment might be, The New York Times analyzed data from S&P Dow Jones Indices that compiled the market values of the companies in the S&P 500 in December 1999 and August 2007. Each date was chosen roughly three months before a downturn to capture the weighted breakdown of the index before crises fully took hold and values fell.

The companies that make up the index have periodically cycled in and out, and the sectors were reclassified over the last two decades. But even after factoring in those changes, the picture that emerges is a market that is becoming increasingly one-sided.

In December 1999, the tech sector made up 26 percent of the total.

In August 2007, just before the Great Recession, it was only 14 percent.

Today, tech is worth a third of the market, as other vital sectors, such as energy and those that include manufacturing, have shrunk.

Since then, the huge growth of the internet, social media and other technologies propelled the economy.

Now, never has so much of the market been concentrated in so few companies. The top 10 make up almost 40 percent of the S&P 500.

How much of the S&P 500 is occupied by the top 10 companies

With greater concentration of wealth comes greater risk. When so much money has accumulated in just a handful of companies, stock trading can be more volatile and susceptible to large swings. One day after Nvidia posted a huge profit for its most recent quarter, its stock price paradoxically fell by 5.5 percent. So far in 2026, more than a fifth of the stocks in the S&P 500 have moved by 20 percent or more. Companies and industries that are seen as particularly prone to disruption by A.I. have been hard hit.

The volatility can be compounded as everyone reorients their businesses around A.I, or in response to it.

The artificial intelligence boom has touched every corner of the economy. As data centers proliferate to support massive computation, the utilities sector has seen huge growth, fueled by the energy demands of the grid. In 2025, companies like NextEra and Exelon saw their valuations surge.

The industrials sector, too, has undergone a notable shift. General Electric was its undisputed heavyweight in 1999 and 2007, but the recent explosion in data center construction has evened out growth in the sector. GE still leads today, but Caterpillar is a very close second. Caterpillar, which is often associated with construction, has seen a spike in sales of its turbines and power-generation equipment, which are used in data centers.

One large difference between the big tech companies now and their counterparts during the dot-com boom is that many now earn money. A lot of the well-known names in the late 1990s, including Pets.com, had soaring valuations and little revenue, which meant that when the bubble popped, many companies quickly collapsed.

Nvidia, Apple, Alphabet and others generate hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue each year.

And many of the biggest players in artificial intelligence these days are private companies. OpenAI, Anthropic and SpaceX are expected to go public later this year, which could further tilt the market dynamic toward tech and A.I.

Methodology

Sector values reflect the GICS code classification system of companies in the S&P 500. As changes to the GICS system took place from 1999 to now, The New York Times reclassified all companies in the index in 1999 and 2007 with current sector values. All monetary figures from 1999 and 2007 have been adjusted for inflation.

Business

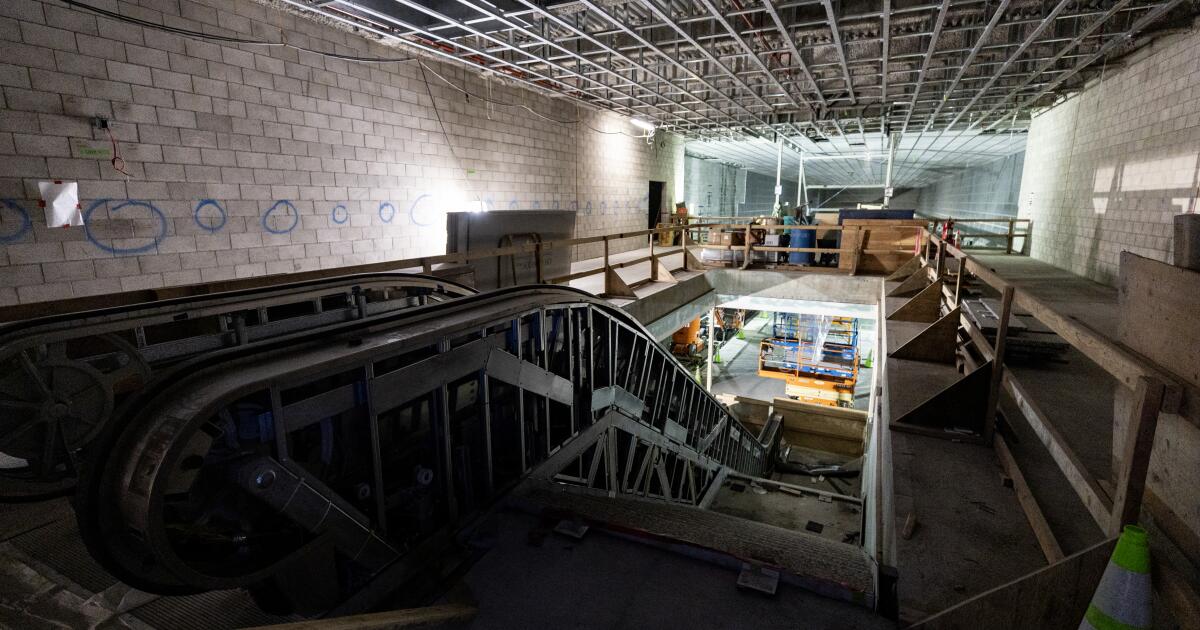

Coming soon: L.A. Metro stops that connect downtown to Beverly Hills, Miracle Mile

Metro has announced it will open three new stations connecting downtown Los Angeles to Beverly Hills in May.

The new stations mark the first phase of a rail extension project on the Metro D line, also known as the Purple Line, beneath Wilshire Boulevard. The extension will open to the public on May 8.

It’s part of a broader plan to enhance the region’s transit infrastructure in time for the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

The new stations will take riders west, past the existing Wilshire/Western station in Koreatown, and stopping along the Miracle Mile before arriving at Beverly Hills. The 3.92-mile addition winds through Hancock Park, Windsor Square, the Fairfax District and Carthay Circle. The stations will be located at Wilshire/La Brea, Wilshire/Fairfax and Wilshire/La Cienega.

This is the first of three phases in the D Line extension project. The completion of the this phase, budgeted at $3.7 billion, comes months later than earlier projections. Metro said in 2025 it expected to wrap up the phase by the end of the year.

The route between downtown Los Angeles and Koreatown is one of Metro’s most heavily used rail lines, with an average of around 65,000 daily boardings. The Purple Line extension project — with the goal of adding seven stations and expanding service on the line to Hancock Park, Century City, Beverly Hills and Westwood — broke ground more than a decade ago. Metro’s goal is to finish by the 2028 Summer Olympics.

In a news release on Thursday, Metro described its D Line expansion as “one of the highest-priority” transit projects in its portfolio and “a historic milestone.”

“Traveling through Mid-Wilshire to experience the culture, cuisine and commerce across diverse neighborhoods will be easier, faster and more accessible,” said Fernando Dutra, Metro board chair and Whittier City Council member, in the release. “That connectivity from Downtown LA to the westside will serve as a lasting legacy for all Angelenos.”

The D line was closed for more than two months last year for construction under Wilshire Boulevard, contributing to a 13.5% drop in ridership that was exacerbated by immigration raids in the area.

“I can’t wait for everyone to enjoy and discover the vibrance of mid-Wilshire without the traffic,” Metro CEO Stephanie Wiggins said in a statement.

-

World1 day ago

World1 day agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana4 days ago

Louisiana4 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making