Business

Column: Disinformation is a public health crisis. Here's how scientists and doctors are fighting it

In recent years, disinformation has seemed to be on an inexorable march across the scientific and medical landscape.

Prominent politicians, up to and including the former president, have promoted useless drugs as supposed cures for COVID-19. Partisan attacks on the safety and efficacy of COVID vaccines have expanded into attacks on all vaccines. Established scientific and medical authorities have been vilified on social media and on the airwaves and even been subjected to physical assault.

The sheer volume of lies and misrepresentations injected into the political mainstream has some scientists despairing of ever regaining the public’s attention.

“Scientists really recognize this as a problem, from what they see in the community and read in the news,” says Tara Kirk Sell of Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Health Security. “They see the problems they have from misinformation and disinformation on the public health side and in the medical field and in other areas. They want to figure out how to deal with it. We’re providing some guidance for combating it and making people more resistant to it.”

Sell’s reference is to the “Practical Playbook for Addressing Health Misinformation” just released by her center. The 65-page publication amounts to a road map for identifying misinformation and disinformation and applying the best strategies for counteracting it before it spreads.

It’s part of an emerging genre of advice for scientists, public health officials and others who get confronted by rumors that interfere with their work, or by deliberate falsehoods; the latter is “disinformation,” as opposed to “misinformation,” which may simply be widely accepted misunderstandings that may have innocent sources.

UNICEF, the Yale Institute for Global Health and other organizations published one of the earliest such guides in late 2020, aimed specifically at anti-vaccine misinformation. Others have the broader goal of fighting conspiracy theories in general.

One recommendation that most seem to have in common is to take a strategic approach: Disinformation campaigns can’t be defeated by ad-hoc measures; they require an organized, proactive and targeted approach mounted by credible defenders of science.

The effort is important because the disinformation has more than political consequences; it costs lives. Pseudoscience debunker Peter Hotez calculates that as many as 200,000 Americans may have perished because of COVID after the vaccines were introduced because anti-vaccine propaganda dissuaded them from getting the shots.

Cases of measles, which should have been eradicated in the U.S. years ago, are appearing again because of disinformation about the vaccines. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention counts more than 20 measles cases so far this year in at least 11 states. That’s about one-third of the 58 cases recorded in all of last year, counted in only the first six weeks of 2024, suggesting that a more serious epidemic may loom on the horizon.

Six cases have occurred in a single school in Florida, a state whose Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, has placed anti-vaccine propaganda at the center of his public health policies. The school’s measles vaccination rate is about 89%, well below the 95% level thought to provide communal immunity protecting even the unvaccinated.

Scientists … see the problems they have from misinformation and disinformation on the public health side, and in the medical field and in other areas. They want to figure out how to deal with it.

— Tara Kirk Sell, Johns Hopkins university

As I’ve reported before, the politicization of anti-COVID measures has turbocharged healthcare disinformation more generally. In part, the reason may be that the pandemic brought public health efforts out of the shadows.

“Often, public health has been an invisible force for good,” Sell told me. “People don’t really notice it because they don’t notice not getting sick and not getting food poisoning.” During the pandemic, however, “people saw public health acting in a more visible way, that made them aware, and sometimes a little bit scared, that sometimes public health measures can be restrictive.”

Sell acknowledges that the battle against disinformation has gotten harder. One reason is that more of it emanates from government sources.

That’s a novel issue. At a simulation exercise on pandemic responses that Sell’s institute hosted for business and public health officials in October 2019, one question that came up was: What if misinformation or disinformation comes from government?

The conclusion was “that’s a crazy question,” Sell told me. “Now, it doesn’t seem that crazy. We’ve seen a lot of it.”

At a House hearing just last week, for instance, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) staged an attack on COVID vaccines consisting of misleading statistics presented out of context, unverified claims of side effects and flagrant misstatements about the consequences of COVID infection.

As I’ve reported, one of the nation’s most assiduous dispensers of anti-vaccine claptrap does so from an official perch. He’s Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo, who was inserted into his post by DeSantis, who may be the nation’s second-most-dangerous official offender against good sense and sound public health policy.

Ladapo’s approach to the Florida measles outbreak, which includes downplaying the need for children to be vaccinated and allowing parents to make their own decision about sending even unvaccinated children to schools experiencing an outbreak, runs counter to recommendations from the CDC. The CDC places vaccination at the very top of its recommendations for preventing the disease and advises isolating those who may transmit the virus.

A problem of longer standing for anti-disinformation crusaders is encompassed in Brandolini’s Law, coined in 2013 by Alberto Brandolini, an Italian software engineer. Cleaned up, it states, “The amount of energy needed to refute [B.S.] is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it.”

To put it another way, disinformation peddlers need only make a claim that sounds plausible or might even have a small kernel of truth to influence the unwary. Debunking or refuting their assertions often requires offering nuanced or technical information that doesn’t have the same pizzazz.

Recognizing disinformation techniques and how they implant sticky but erroneous concepts in the minds of laypersons, Sell says, points to some useful rules of engagement. One is the value of “prebunking” — “addressing or refuting potential false information” before it’s widely disseminated, as the Johns Hopkins handbook puts it.

“People are not that creative,” she says. “They use the same stories over and over again with different health threats. You can expect that with any vaccination campaign there will be an infertility rumor, no matter what vaccine it is, or a rumor that a vaccine has been experimented on children. We see that every time. They work because they resonate” with target audiences — such as pregnant women or parents of small children.

“People need to be shown how to recognize disinformation tactics, such as an appeal to emotion” or personal stories of adverse side effects that are claimed to be representative of patients as a whole rather than rare occurrences.

It may also help to highlight the motivations of anti-science propagandists, who spread disinformation “often for social, political or financial gain.” Indeed, as the Washington Post recently documented from tax records, four nonprofit organizations that marketed medical misinformation during the pandemic saw their contributions leap by more than $100 million from 2020 to 2022.

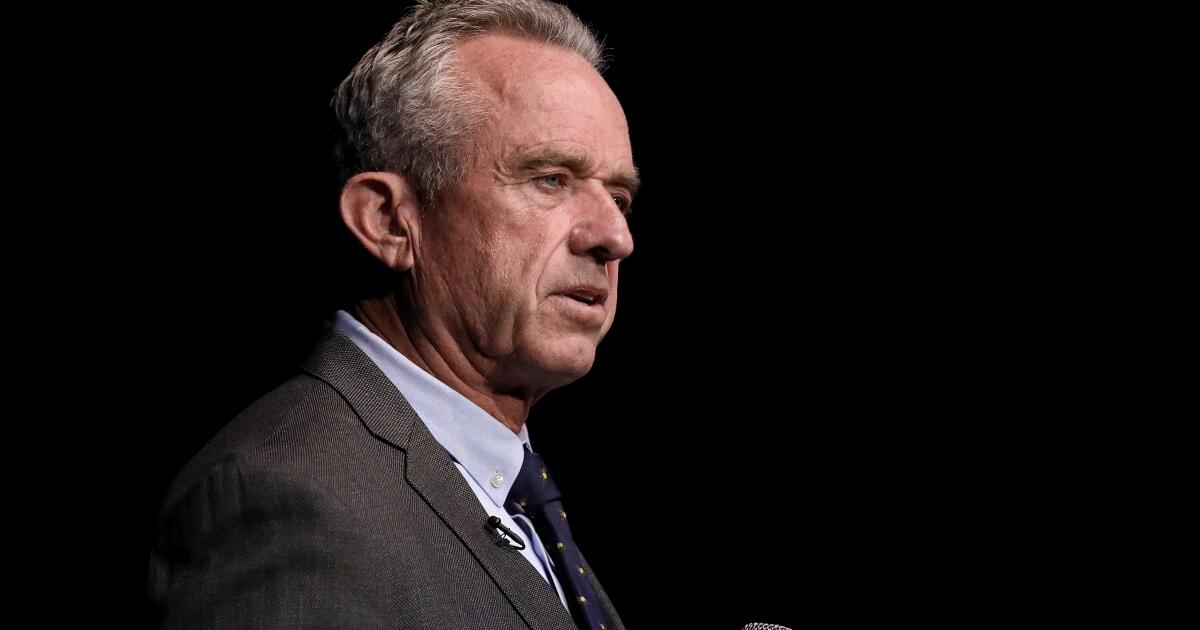

Among them is Children’s Health Defense, the anti-vaccine group founded by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who is currently trying to ride his anti-vaccine crusade to the Oval Office.

The lessons of the pandemic may help the public health community avoid some of the mistakes that allowed the disinformation lobby to undermine the public’s trust in scientists and medical experts, a crucial factor in its campaigns. The CDC and other public health agencies sometimes changed their recommendations on anti-COVID policies.

That was hardly an unexpected occurrence, since so little was known at first about the virus, its effects and the most suitable treatments. But it gave their adversaries the opening they needed to question the severity of the outbreak or the policy recommendations themselves, and to promote useless nostrums.

“Public health needs to be transparent about the reasons why advice is changing,” Sell says, “explaining that if you didn’t change with new evidence, you would be doing a disservice to the public. Maybe we didn’t do a good enough job in this pandemic in saying we’re going to learn more, and our advice may change. And we’ll do our best to keep you as informed as possible as that advice changes.”

The challenge of fighting the fire hose of falsity being trained on science has made some scientists cynical about the prospects of victory, Sell acknowledges. “The Playbook is not a silver bullet,” she says. “But it helps. There are things to be done, and we can’t give up. Attacking misinformation in as many different ways as possible is something we’re going to have to do.”

Business

U.S. Space Force awards $1.6 billion in contracts to South Bay satellite builders

The U.S. Space Force announced Friday it has awarded satellite contracts with a combined value of about $1.6 billion to Rocket Lab in Long Beach and to the Redondo Beach Space Park campus of Northrop Grumman.

The contracts by the Space Development Agency will fund the construction by each company of 18 satellites for a network in development that will provide warning of advanced threats such as hypersonic missiles.

Northrop Grumman has been awarded contracts for prior phases of the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, a planned network of missile defense and communications satellites in low Earth orbit.

The contract announced Friday is valued at $764 million, and the company is now set to deliver a total of 150 satellites for the network.

The $805-million contract awarded to Rocket Lab is its largest to date. It had previously been awarded a $515 million contract to deliver 18 communications satellites for the network.

Founded in 2006 in New Zealand, the company builds satellites and provides small-satellite launch services for commercial and government customers with its Electron rocket. It moved to Long Beach in 2020 from Huntington Beach and is developing a larger rocket.

“This is more than just a contract. It’s a resounding affirmation of our evolution from simply a trusted launch provider to a leading vertically integrated space prime contractor,” said Rocket Labs founder and chief executive Peter Beck in online remarks.

The company said it could eventually earn up to $1 billion due to the contract by supplying components to other builders of the satellite network.

Also awarded contracts announced Friday were a Lockheed Martin group in Sunnyvalle, Calif., and L3Harris Technologies of Fort Wayne, Ind. Those contracts for 36 satellites were valued at nearly $2 billion.

Gurpartap “GP” Sandhoo, acting director of the Space Development Agency, said the contracts awarded “will achieve near-continuous global coverage for missile warning and tracking” in addition to other capabilities.

Northrop Grumman said the missiles are being built to respond to the rise of hypersonic missiles, which maneuver in flight and require infrared tracking and speedy data transmission to protect U.S. troops.

Beck said that the contracts reflects Rocket Labs growth into an “industry disruptor” and growing space prime contractor.

Business

California-based company recalls thousands of cases of salad dressing over ‘foreign objects’

A California food manufacturer is recalling thousands of cases of salad dressing distributed to major retailers over potential contamination from “foreign objects.”

The company, Irvine-based Ventura Foods, recalled 3,556 cases of the dressing that could be contaminated by “black plastic planting material” in the granulated onion used, according to an alert issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Ventura Foods voluntarily initiated the recall of the product, which was sold at Costco, Publix and several other retailers across 27 states, according to the FDA.

None of the 42 locations where the product was sold were in California.

Ventura Foods said it issued the recall after one of its ingredient suppliers recalled a batch of onion granules that the company had used n some of its dressings.

“Upon receiving notice of the supplier’s recall, we acted with urgency to remove all potentially impacted product from the marketplace. This includes urging our customers, their distributors and retailers to review their inventory, segregate and stop the further sale and distribution of any products subject to the recall,” said company spokesperson Eniko Bolivar-Murphy in an emailed statement. “The safety of our products is and will always be our top priority.”

The FDA issued its initial recall alert in early November. Costco also alerted customers at that time, noting that customers could return the products to stores for a full refund. The affected products had sell-by dates between Oct. 17 and Nov. 9.

The company recalled the following types of salad dressing:

- Creamy Poblano Avocado Ranch Dressing and Dip

- Ventura Caesar Dressing

- Pepper Mill Regal Caesar Dressing

- Pepper Mill Creamy Caesar Dressing

- Caesar Dressing served at Costco Service Deli

- Caesar Dressing served at Costco Food Court

- Hidden Valley, Buttermilk Ranch

Business

They graduated from Stanford. Due to AI, they can’t find a job

A Stanford software engineering degree used to be a golden ticket. Artificial intelligence has devalued it to bronze, recent graduates say.

The elite students are shocked by the lack of job offers as they finish studies at what is often ranked as the top university in America.

When they were freshmen, ChatGPT hadn’t yet been released upon the world. Today, AI can code better than most humans.

Top tech companies just don’t need as many fresh graduates.

“Stanford computer science graduates are struggling to find entry-level jobs” with the most prominent tech brands, said Jan Liphardt, associate professor of bioengineering at Stanford University. “I think that’s crazy.”

While the rapidly advancing coding capabilities of generative AI have made experienced engineers more productive, they have also hobbled the job prospects of early-career software engineers.

Stanford students describe a suddenly skewed job market, where just a small slice of graduates — those considered “cracked engineers” who already have thick resumes building products and doing research — are getting the few good jobs, leaving everyone else to fight for scraps.

“There’s definitely a very dreary mood on campus,” said a recent computer science graduate who asked not to be named so they could speak freely. “People [who are] job hunting are very stressed out, and it’s very hard for them to actually secure jobs.”

The shake-up is being felt across California colleges, including UC Berkeley, USC and others. The job search has been even tougher for those with less prestigious degrees.

Eylul Akgul graduated last year with a degree in computer science from Loyola Marymount University. She wasn’t getting offers, so she went home to Turkey and got some experience at a startup. In May, she returned to the U.S., and still, she was “ghosted” by hundreds of employers.

“The industry for programmers is getting very oversaturated,” Akgul said.

The engineers’ most significant competitor is getting stronger by the day. When ChatGPT launched in 2022, it could only code for 30 seconds at a time. Today’s AI agents can code for hours, and do basic programming faster with fewer mistakes.

Data suggests that even though AI startups like OpenAI and Anthropic are hiring many people, it is not offsetting the decline in hiring elsewhere. Employment for specific groups, such as early-career software developers between the ages of 22 and 25 has declined by nearly 20% from its peak in late 2022, according to a Stanford study.

It wasn’t just software engineers, but also customer service and accounting jobs that were highly exposed to competition from AI. The Stanford study estimated that entry-level hiring for AI-exposed jobs declined 13% relative to less-exposed jobs such as nursing.

In the Los Angeles region, another study estimated that close to 200,000 jobs are exposed. Around 40% of tasks done by call center workers, editors and personal finance experts could be automated and done by AI, according to an AI Exposure Index curated by resume builder MyPerfectResume.

Many tech startups and titans have not been shy about broadcasting that they are cutting back on hiring plans as AI allows them to do more programming with fewer people.

Anthropic Chief Executive Dario Amodei said that 70% to 90% of the code for some products at his company is written by his company’s AI, called Claude. In May, he predicted that AI’s capabilities will increase until close to 50% of all entry-level white-collar jobs might be wiped out in five years.

A common sentiment from hiring managers is that where they previously needed ten engineers, they now only need “two skilled engineers and one of these LLM-based agents,” which can be just as productive, said Nenad Medvidović, a computer science professor at the University of Southern California.

“We don’t need the junior developers anymore,” said Amr Awadallah, CEO of Vectara, a Palo Alto-based AI startup. “The AI now can code better than the average junior developer that comes out of the best schools out there.”

To be sure, AI is still a long way from causing the extinction of software engineers. As AI handles structured, repetitive tasks, human engineers’ jobs are shifting toward oversight.

Today’s AIs are powerful but “jagged,” meaning they can excel at certain math problems yet still fail basic logic tests and aren’t consistent. One study found that AI tools made experienced developers 19% slower at work, as they spent more time reviewing code and fixing errors.

Students should focus on learning how to manage and check the work of AI as well as getting experience working with it, said John David N. Dionisio, a computer science professor at LMU.

Stanford students say they are arriving at the job market and finding a split in the road; capable AI engineers can find jobs, but basic, old-school computer science jobs are disappearing.

As they hit this surprise speed bump, some students are lowering their standards and joining companies they wouldn’t have considered before. Some are creating their own startups. A large group of frustrated grads are deciding to continue their studies to beef up their resumes and add more skills needed to compete with AI.

“If you look at the enrollment numbers in the past two years, they’ve skyrocketed for people wanting to do a fifth-year master’s,” the Stanford graduate said. “It’s a whole other year, a whole other cycle to do recruiting. I would say, half of my friends are still on campus doing their fifth-year master’s.”

After four months of searching, LMU graduate Akgul finally landed a technical lead job at a software consultancy in Los Angeles. At her new job, she uses AI coding tools, but she feels like she has to do the work of three developers.

Universities and students will have to rethink their curricula and majors to ensure that their four years of study prepare them for a world with AI.

“That’s been a dramatic reversal from three years ago, when all of my undergraduate mentees found great jobs at the companies around us,” Stanford’s Liphardt said. “That has changed.”

-

Iowa6 days ago

Iowa6 days agoAddy Brown motivated to step up in Audi Crooks’ absence vs. UNI

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoHow much snow did Iowa get? See Iowa’s latest snowfall totals

-

Maine4 days ago

Maine4 days agoElementary-aged student killed in school bus crash in southern Maine

-

Maryland6 days ago

Maryland6 days agoFrigid temperatures to start the week in Maryland

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThe Game Awards are losing their luster

-

South Dakota6 days ago

South Dakota6 days agoNature: Snow in South Dakota

-

New Mexico4 days ago

New Mexico4 days agoFamily clarifies why they believe missing New Mexico man is dead

-

Nebraska1 week ago

Nebraska1 week agoNebraska lands commitment from DL Jayden Travers adding to early Top 5 recruiting class