Business

Column: Conservative attacks on abortion depend on a law that courts have snubbed for 150 years

Nothing reflects that show-stopping lyric “everything old is new again” like the tactics of the antiabortion movement — specifically, its reliance on a long-discredited 1873 law to eviscerate women’s healthcare rights in the modern age.

The law is the Comstock Act, which Congress passed during the post-Civil War period of puritan reaction at the behest of one of the outstanding bluenoses of American history.

The law drafted by Anthony Comstock, passed by Congress and signed by President Grant outlawed the mailing of any “obscene, lewd, or lascivious book, pamphlet, picture, paper, print or other publication of an indecent character, … or any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion.” Penalties ranged up to 10 years.

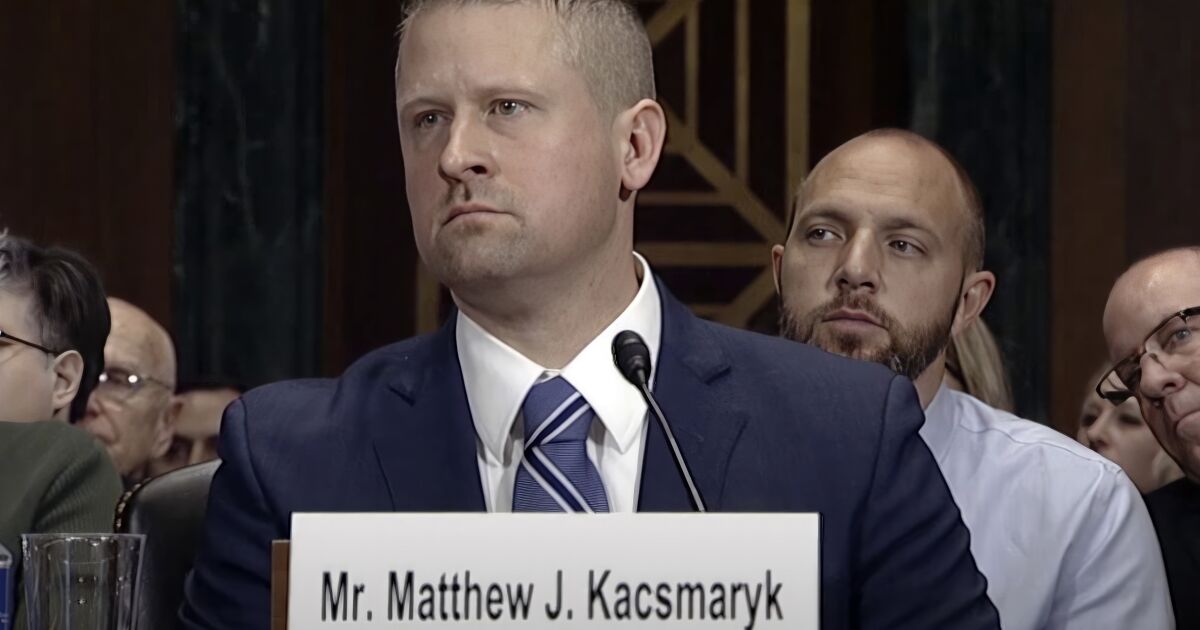

The Comstock Act plainly forecloses mail-order abortion in the present.

— U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, citing a law from 1873

By any measure, the law is an antique. Yet it was cited in the April 7 ruling by Trump-appointed federal Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk reversing the Food and Drug Administration’s 20-year-old approval of the abortion drug mifepristone.

Kacsmaryk’s conclusion that the “plain text” of the act renders mailing the drug illegal was viewed kindly by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which temporarily stayed his ruling but observed that it may weigh in favor of the antiabortion activists who brought the case challenging the FDA.

(The appellate court held a hearing in the case Wednesday in which the three GOP-appointed judges on the panel overtly favored the antiabortion side. The Comstock Act issue came up only once, briefly, but the FDA’s lawyer maintained only that issues other than the agency’s drug-approval process aren’t relevant.)

There are indications that antiabortion activists, if they prevail in this case, might try to exploit the Comstock Act to interfere with the shipment not only of mifepristone but of any drugs, equipment or paraphernalia that could be used for abortions.

A literal, 1870s-era reading of the act might even bar advertising or information about abortion, and could be used to restrict contraceptives.

The law went through numerous alterations on its way to enactment, however, and has been consistently narrowed over the subsequent 150 years by federal court rulings and congressional revisions. A Justice Department analysis last year drew on this history to declare that using the law as an antiabortion tactic runs directly counter to legal precedent.

The Comstock Act’s role in the case now before the federal courts warrants taking a closer look at its creator and its context.

As an anti-obscenity crusader, Comstock had the backing of wealthy patrons. They included Morris K. Jesup, a banker and philanthropist best known as a founder of the American Museum of Natural History, but who also co-founded the Committee for the Suppression of Vice, which Comstock chaired.

Another was Samuel Colgate, whose soap manufacturing company became the target of a years-long boycott launched by “freethinkers throughout the country,” according to Comstock biographers Heywood Broun and Margaret Leech.

Anthony Comstock first swam into public attention with a campaign against the spiritualist and women’s rights activist Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennessee Claflin. The pair had established the first Wall Street brokerage owned by women in 1870 (though it was bankrolled by Cornelius Vanderbilt, a lover of Tennessee and a devotee of the sisters’ spirit communications). Woodhull later ran for president on a platform that included free love.

Comstock brought a federal lawsuit against the sisters over reports they published in their weekly newspaper about a scandal involving the eminent clergyman Henry Ward Beecher, who was accused of an adulterous affair with a friend’s wife. In time, Beecher was exonerated in court and by his Congregational church elders, and the obscenity case against the sisters was dismissed.

The case, however, made Comstock’s name synonymous with “prudery, Puritanism and officious meddling,” according to Broun and Leech. Proving the adage that no publicity is bad publicity, Comstock would ride his renown to greater fame.

Due to his aggressive and often theatrical attacks on booksellers and publishers, Comstock also became a figure of public ridicule. He drew brickbats from none other than George Bernard Shaw after trying to shut down a New York production of Shaw’s “Mrs. Warren’s Profession.”

In that play, Shaw depicted prostitution not as a moral failing but — as he wrote in his preface to the work — a result of “underpaying, undervaluing, and overworking women so shamefully that the poorest of them are forced to resort to prostitution to keep body and soul together.”

Even the mention of prostitution and brothel-keeping offended Comstock’s sensibilities, though he never attended or even read the play.

Anti-obscenity crusader Anthony Comstock, lampooned in a 1915 periodical. The caption read: “Your Honor, this woman gave birth to a naked child.”

“Comstockery is the world’s standing joke at the expense of the United States,” Shaw commented. “Europe likes to hear of such things. It confirms the deep-seated conviction of the old world that America is a provincial place, a second rate country town civilization after all.”

(“I never heard of him in my life,” Comstock said of Shaw, according to the newspapers. “Never saw one of his books, so he can’t be much.”)

Comstock’s main targets in drafting his law were obscenity and pornography. He was also an antiabortion crusader, so he threw a ban on the mailing of drugs or materials used for abortion into the draft as a secondary matter.

Congress passed the law in March 1873, acting hastily and without extended discussion, in part because it was distracted by the Credit Mobilier case, a scandal that embroiled numerous representatives and senators in accusations of bribery by railroad investors.

The law Congress originally passed referred to “unlawful” abortions, but that qualification disappeared from a restatement of the law in 1948.

Almost immediately after the law’s passage, Comstock was appointed a special agent of the post office, which allowed him to step up his campaigns against obscenity and abortion.

Judges and juries ruling on anti-obscenity complaints brought by Comstock often were flying blind, for the material in question could not be mentioned or displayed in court during those oversensitive times. Therefore, they had to rely on prosecutors’ descriptions of what was so offensive.

Any hint of nudity in a picture displayed in a shop window, even in a classical artistic context, was likely to attract a Comstock demand for its removal or lead to a prosecution.

Looking back on his career just before his death in 1915, Comstock boasted of having “convicted persons enough to fill a passenger train of sixty-one coaches,” and having “destroyed 160 tons of obscene literature.” Among his targets were some volumes deemed classics of European literature even then, including Bocaccio’s “Decameron.”

“Many of these stories,” he wrote, “are little better than histories of brothels and prostitutes, in these lust-cursed nations.” The result of exposure to such material was “a putting of vile thoughts and suggestions into the minds of the young, sowing the seeds of lust.”

However, “Comstock had no great luck among the so-called abortionists,” Broun and Leech found, achieving a lower percentage of convictions than against accused pornographers. When he did win a case, judges tended to levy small fines and no jail time.

As time passed, the environment in which the Comstock Act was passed came to seem almost quaint. Courts eventually overturned the provisions related to written and published works on 1st Amendment grounds. Congress removed the restrictions on mailing contraceptives in 1971.

Further court rulings established that the strictures on the shipping of abortion-related materials required that the senders intended that the recipient would use them unlawfully — that is, for abortions where that procedure was illegal.

That issue never came up after the Supreme Court’s Roe vs. Wade ruling in 1973 made abortion legal nationwide. Even after the court overturned Roe vs. Wade with its decision in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization last year, the Justice Department noted in its analysis, since mifepristone has nonabortion uses and since even states with the strictest antiabortion laws allowed the procedure to save the life of the mother, it would be almost impossible to establish that a sender intended that it be used unlawfully. In other words, the Comstock Act was effectively unenforceable.

As I’ve reported before, court rulings in 1915, 1930, 1933, 1936, 1938, 1944 and 1962, and congressional revisions in 1945, 1955, 1958, 1971 and 1994 relegated the original language of the Comstock Act to the dustbin.

The U.S. Postal Service has accepted the narrowed interpretations in its own administrative proceedings and presented its position explicitly to Congress, which never objected.

Judge Kacsmaryk willfully ignored all those years of statutory evolution in ruling that “the Comstock Act plainly forecloses mail-order abortion in the present.”

It might have been safe to assume that not even the most obdurate antiabortion conservatives could expect to resurrect the act and turn the clock back to the Comstockian world of 1873.

That might not be a safe assumption anymore, since the case appears destined for Supreme Court review. Since the current Supreme Court has shown no compunctions about disrespecting precedents of long standing, when it comes to women’s healthcare we may yet find ourselves transported back to the 19th century.

Business

Sony warns tech companies: Don't use our music to train your AI

Sony Music Group is sending letters to 700 artificial intelligence developers and music streaming services warning them to not use its artists’ music to train generative AI tools without its permission.

The company — one of the three largest recorded music firms — said it is explicitly opting out of the use of its music for training or developing AI models through text or data mining or web scraping as it relates to lyrics, audio recordings, artwork, musical compositions and images. Sony Music Group artists include Celine Dion, Doja Cat and Harry Styles.

“We support artists and songwriters taking the lead in embracing new technologies in support of their art,” Sony Music Group said in a statement on its website Thursday. “Evolutions in technology have frequently shifted the course of creative industries. … However, that innovation must ensure that songwriters’ and recording artists’ rights, including copyrights, are respected.”

The letters were sent to companies including San Francisco-based ChatGPT creator OpenAI and Mountain View-based search giant Google, according to a person familiar with the matter who was not authorized to speak publicly. OpenAI and Google did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The move comes as the entertainment industry is grappling with rapid innovations in artificial intelligence technology. Writers and actors raised concerns last summer about whether leaving AI unchecked could threaten their livelihoods. Meanwhile, some creatives have marveled at the advancements that could allow them to pursue bold ideas with tight budgets.

This year, OpenAI unveiled its text-to-video tool Sora, which was used to create a four-minute music video for music artist Washed Out. The director of the video told The Times that Sora helped him depict multiple locations and visual effects that he otherwise couldn’t have.

But AI can also create chaos. Celebrities have dealt with “deep fakes” — false videos or audio depicting a celebrity endorsing certain brands or activities. To help protect their clients against unauthorized use of their voice and likeness, Century City-based Creative Artists Agency is helping talent create their own digital doubles.

On Thursday, two New York voice-over actors sued Berkeley-based AI voice generator business Lovo for unauthorized use of their voices. Lovo did not immediately return a request for comment. The lawsuit was filed in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Some people in the entertainment industry have said they would like the AI companies to be more transparent about how they are training their tools and whether they have the appropriate copyright permissions.

OpenAI has said its large language models, including those that power ChatGPT, are developed through information available publicly on the internet, material acquired through licenses with third parties and information its users and “human trainers” provide.

The company said in a blog post that it believes training AI models on publicly available materials on the internet is “fair use.”

But some media outlets, including the New York Times, have sued OpenAI. The newspaper raised alarms about how its stories are being used by the tech company.

In Sony Music Group’s letters to AI businesses, the company said it has reason to believe its content may have been used to train, develop or commercialize artificial intelligence systems without its permission, according to a copy obtained by the Times. Sony Music Group asked the tech companies to provide information regarding that use and why it was necessary.

Sony Music Group, owned by Tokyo-based electronics giant Sony Corp., also wants music streaming providers to add language in its terms of service saying that third parties are not allowed to mine and train using Sony Music Group content, the person familiar with the matter said.

Business

A woman was dragged by a self-driving Cruise taxi in San Francisco. The company is paying her millions

General Motors’ autonomous car company, Cruise, has reportedly agreed to pay an $8-million to $12-million settlement to a woman who was hospitalized after getting dragged along the pavement by a self-driving taxi in San Francisco last year.

The woman, a pedestrian, was struck by a hit-and-run vehicle at 5th and Market streets and thrown into the path of Cruise’s self-driving car, which pinned her underneath, according to Cruise and authorities. The car dragged her about 20 feet as it tried to pull out of the roadway before coming to a stop.

She sustained “multiple traumatic injuries” and was treated at the scene before being hospitalized.

It’s unclear when the settlement was reached or the exact amount, sources familiar with the situation told Fortune and Bloomberg. The condition of the woman, whose name was not released by authorities, is unknown, but a representative of Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital told Fortune that she had been discharged.

Cruise initially said that its self-driving car “braked aggressively to minimize impact” but later said the vehicle’s software made a mistake in registering where it hit the woman. The car tried to pull over but continued driving 7 mph for 20 feet with the woman still under the vehicle.

“The hearts of all Cruise employees continue to be with the pedestrian, and we hope for her continued recovery,” Cruise said in a statement.

Cruise halted its driverless operations after its autonomous taxi license was suspended by California’s Department of Motor Vehicles. The company was also accused of lying to investigators and withholding footage of the car crash.

Cruise said this week that it would start testing robotaxis in Arizona with a “safety driver” behind the wheel in case a human needs to take control of the vehicle, according to a company news release.

“Safety is the defining principle for everything we do and continues to guide our progress towards resuming driverless operations,” according to the release.

Business

How YouTube became must-see TV: Shorts, sports and Coachella livestreams

When YouTube launched nearly two decades ago, its first clip was a grainy video of co-founder Jawed Karim speaking to the camera while standing in front of the elephants at the San Diego Zoo.

Not exactly must-see TV.

Since, then the online video giant has increasingly been the entertainment of choice for billions of people. And while the Google-owned service is still often thought of as being the destination for people watching funny short videos on their smartphones, the way that Americans watch it has changed in a big way.

People are increasingly choosing to watch YouTube on their connected TVs rather than on laptops and mobile devices, treating it more and more like a regular television destination.

The San Bruno, Calif.-based video giant said more than 150 million people in the U.S. are watching YouTube on connected TV screens every month, citing December 2022 data. That’s up 11% from 2021. YouTube is consistently the most watched streaming service in the U.S. on a TV in the U.S. every month, even beating Netflix and Amazon’s Prime Video since February 2023, according to Nielsen. The service accounts for nearly 10% of television viewing, the data firm said.

According to research firm Emarketer, U.S. adults spend 36 minutes each day watching YouTube, with 17 of those minutes on a connected TV, four minutes on a desktop or laptop computer and 15 minutes on a mobile device.

A variety of content is driving the company’s evolution. YouTube said TVs accounted for more than 50% of the watch time for its Coachella livestream this year, which is higher than ever before. Views of Shorts, clips that are 60 seconds or less, on connected TVs more than doubled last year, YouTube said.

“We’ve invested in making sure that YouTube really captures the totality of the experience that people want,” said Christian Oestlien, YouTube’s vice president of product management for connected TV. “What we hear from our users is they want to be able to watch their favorite creators but also highlights from their favorite sporting events, listen to their favorite artist and watch their favorite podcast and do it all in this one contained experience.”

At a time when consumers are choosing between multiple streaming services, YouTube has an advantage of having a wide variety of options, from live sports to user-generated videos. The company said the increase in TV watch time comes as connected TVs are becoming more widely available.

TV screen time can be helpful to streamers wishing to court more advertising dollars. This week, television networks and streaming services Amazon and Netflix made gala presentations to advertisers, showing off the programming they have coming up.

YouTube on Wednesday presented to advertisers new features such as branded QR codes and non-skippable assets on connected TVs.

“YouTube is wanting to position themselves not just as a digital advertising option, they want advertisers to see them on the same advertising footing as any other streaming service,” said Brett Sappington, founder of Dallas-based media and insights firm Sappington Media.

YouTube has introduced features to improve the television viewing experience, including the option to watch Coachella performances through a four-way split screen. The company also has shopping options.

“This isn’t my dad’s TV or my grandma’s TV,” Oestlien said. “This is TV rethought for a new generation.”

YouTube video creators have also embraced TV viewing, Oestlien said. In the last three years, the number of top YouTube creators who receive most of their watch time from TV screens has quintupled, YouTube said.

YouTube has also gotten a boost from its deal to become the home of pro football’s “NFL Sunday Ticket” game package. Fans will watch live games on YouTube on Sunday, then come back and watch clips through its video library or commentary from its creators, Oestlien said.

“It really becomes this surround-sound experience where, as a football fan, you can come to YouTube any day of the week,” he said.

YouTube and other streaming services have been competing for sports league rights in order to increase viewership. Amazon has the NFL’s “Thursday Night Football” games and has bid for a package of NBA matches. On Wednesday, Netflix announced it had secured two Christmas NFL games for 2024.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoBiden takes role as bystander on border and campus protests, surrenders the bully pulpit

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'You need to stop': Gov. Noem lashes out during heated interview over book anecdote about killing dog

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRFK Jr said a worm ate part of his brain and died in his head

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoMan, 75, confesses to killing wife in hospital because he couldn’t afford her care, court documents say

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPentagon chief confirms US pause on weapons shipment to Israel

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHere's what GOP rebels want from Johnson amid threats to oust him from speakership

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPro-Palestine protests: How some universities reached deals with students

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoConvicted MEP's expense claims must be published: EU court