Alaska

Spinnakers, Sweat, and Survival: A Race to Alaska Adventure | Cruising World

Taylor Bayly/Courtesy R2AK

I held my breath as I pulled up the sock to unfurl our spinnaker in Haro Strait. Of the five headsails we’d brought aboard our Santa Cruz 27, this enormous black parachute was the only one I hadn’t bonded with before we’d cast off dock lines in Victoria, British Columbia. We were 50 miles into the 750-mile Race to Alaska—a somewhat insane wilderness adventure where 30-odd teams pedal, paddle and sail a hodgepodge of random crafts from Port Townsend, Washington, to Ketchikan, Alaska—and I was about to learn how to fly a kite for the first time.

Sure, I’ve been aboard other sailboats a handful of times when spinnakers were flown. It always involved male captains wanting to go faster around buoys in big winds; zero discussion of how we would raise, douse or jibe the giant sail; and terrifying near-disasters that elicited lots of confused yelling. So I’d learned only to fear spinnakers, not fly them.

I hoped that this time would be different. The wind was a measly 5 knots, barely filling our genoa. We had a destination that was still days away. And we were a crew of three mid-40s women who were cautious, conscientious, and considerate of one another’s fears.

Our team, Sail Like A Mother, almost didn’t bring any of the spinnakers that came with the boat because none of us had much experience flying them. But we knew we’d likely need at least one in our quiver to navigate the fickle winds of the Inside Passage—especially if we wanted to finish the race before the “Grim Sweeper” tapped us out.

Taylor Bayly/Courtesy R2AK

We decided to bring the asymmetric spinnaker, but only after we attached a sock to douse it quickly. We also made sure at least one crewmember, Melissa Roberts, practiced rigging and sailing it in Bellingham Bay prior to the race.

Melissa let out a whoop from the cockpit as the beautiful black sail snapped taut and Wild Card surged forward: “I knew we could do it! I’m so proud of us!” She played out the working sheet and told me to “just steer to fill the sail when it luffs.” Katie Gaut, our team captain, took photos to memorialize the moment.

I stood with the tiller between my legs to feel our course rather than overthink it. It was lovely and sunny, humpbacks were spouting on the horizon, and we were cruising along at the same speed as the wind. After a half-hour, I decided that the spinnaker was my new favorite sail.

That is, until we had to jibe. In the middle of a shipping lane. While three other Race to Alaska teams were watching.

We promptly lost the lazy sheet under the keel, along with our pride. After a few (quietly) yelled questions, I retrieved the sodden rope while Katie took the tiller. This time, we put a stopper knot in it. Then we kept puttering north at jogging speed.

That is, until it got gusty at sunset, and we got nervous and doused it. Which meant the wind promptly died, of course. We gave up on sails and took turns pedaling the bike instead (it’s a contraption attached to our stern that turned an airplane propeller and moved us at 2 knots). Around 1 a.m., we finally made it to Tumbo Island, British Columbia, dropped anchor, crammed ourselves into our coffin berths in the damp cabin, and got four glorious hours of sleep.

Then we rinsed and repeated for 10 more days.

You might be thinking that the Race to Alaska sounds like your personal version of hell. It’s actually hell intermixed with pockets of pure heaven.

Unlike other races that are fraught with complex regulations, the Race to Alaska—or R2AK—is purposefully simple. There are no motors. No outside support. The Northwest Maritime Center first hatched the race in 2015 with this well-thought-out plan: “We’re going to nail $10,000 to a tree, blow a horn, and whoever gets there first, gets it,” says Jesse Wiegel, the center’s race boss.

Second prize? A set of steak knives. This tongue-in-cheek reward, Wiegel says, drives home the point that people choose to compete in this maritime endurance event for plenty of reasons that are more valuable than cash. Or cutlery.

Taylor Bayly/Courtesy R2AK

For me, those reasons were threefold. I wanted to prove to myself that I could sail offshore without my husband, who had recently decided that he wanted a break from boats. I wanted to inject some adrenaline into my domestic life, and to show my two young kids that their mother does (way) more than their dishes and laundry. I wanted to become part of the inspiring, adventure-prioritizing, 800-person-strong R2AK community.

Oh, and I wanted to see a lot of whales.

Even though the coveted steak knives would look lovely beside my set from Goodwill, our team had no desire to win them. Our goal was simply to finish the race in one piece, hopefully still friends at the end, and to suffer as cheerfully as possible along the route.

Navigating the mind-bending logistics to get to the starting line was the hardest part. Once our threesome decided to enter, 10 months prior to the race, we began calling and texting one another approximately 128 times per day to iron out details: What boat should we buy? How do we get said boat back from Ketchikan after the race? What will we eat for five to 25 days at sea without a kitchen or refrigeration? Where will we pee without a head? How much drinking water should we bring, and where will we store it? How will we keep our sleeping bags, socks, gloves, and other sundries dry amid a constant deluge of rain and sea spray?

Answers to those questions: We bought Wild Card, a 1976 racing boat with a turquoise hull that had previously completed the R2AK and was a minor celebrity in the Pacific Northwest racing community. We found a brave volunteer to sail Wild Card back from Ketchikan to Bellingham, and would ship the outboard up on the ferry for him. We would eat dehydrated meals donated by Backpacker’s Pantry, and oodles of snacks such as jerky, chocolate and nuts. We would pee in a bucket and dump it overboard. We would bring 28 gallons of water in four jugs. And we would pray fervently that oversize plastic bags and good luck would keep our gear sort of dry.

Amy Arntson

But first, we had to see if our application would pass the race committee’s muster. The R2AK’s laissez-faire attitude on rules doesn’t extend to letting just anyone compete.

“The vetting process is something we take really seriously,” Wiegel says. “It ultimately boils down to: Do you have what it takes to keep yourself from getting killed? Do you have the judgment to make good calls, even if it’s sometimes going to be the call to quit?”

Our team definitely took the “keep yourself from getting killed” part seriously. We’re mothers, after all. We borrowed a life raft, installed personal locator beacons and lights on our life jackets, mounted a SailProof tablet in the cockpit to navigate easily in all conditions, attached an AIS transmitter so that cargo and cruise ships would see our tiny boat in big seas, and practiced a lot of woman-overboard drills. We had extra pedals, extra tools, backup navigation lights, backup batteries to charge them, and a medical kit that could outfit a small village.

But that didn’t mean I didn’t worry. After sailing more than 10,000 miles across various oceans, I know that stuff goes sideways. Like that time a decade ago when I had to dive overboard in a shipping lane to pull bull kelp out of the engine’s intake while the boat spiraled in a whirlpool amid pea-soup fog. Or the time our mainsail ripped while my family was sailing closehauled in a motorless Sea Pearl in the Bahamas (with me four months pregnant and our 3-year-old napping in the cockpit). That time, we managed a controlled shipwreck on a sliver of sand amid sharp coral to avoid getting sucked out to sea. And don’t get me started on all the times our engine has died, the electrical system has fritzed, or a line has jammed at the worst possible moment—usually right around 2 a.m. in a squall.

When things get hairy, I’ve learned to deal calmly. To think carefully about potential next steps. To rely on the skills of the friends or family beside me. And, most important, to pull the plug if our combined skills are no match for the problem at hand. Our team motto for getting to Ketchikan was easy to agree upon: “Push ourselves, but be safe and have fun.”

Of course, fun is relative on the R2AK. My first time flying the spinnaker was a perfect example of that: Wait five minutes, and the weather will change. Wait another five minutes, and your sky-high confidence will plummet to the seafloor. We faced big winds and opposing tides. We beat for hours and hours (and hours) up Johnstone Strait in 25 to 30 knots of wind—which was, in all honesty, harder than childbirth. We accidentally jibed in the middle of the night way, way too close to a rock in the roily waters of Hecate Strait while careening down 6-foot swells. We ran out of water in the Dixon Entrance and were too tired to eat after sailing 40 hours straight to the finish line. And we changed headsails 7,458 times, give or take.

Shelley Lipke/Courtesy R2AK

But we also saw orcas at sunset and bioluminescence under a full moon. We hobbyhorsed happily over the whitecapped swells on an easy reach all the way across the Strait of Juan de Fuca. We laughed a lot more than we cried. And by the end, we flew that beautiful black spinnaker like it was second nature.

On Day 9, we decided to head offshore in hopes of riding steadier south winds the last 140 miles to Alaska. We also, it turns out, got surprisingly competitive at the end. A handful of teams had been leapfrogging us the last half of the course, and we knew that we could beat them if we took the open-ocean route instead of the winding inside channels.

But keeping pace with those teams also boosted our morale along the way, especially our daily VHF radio chats with soloist Adam Cove on Team Wicked Wily Wildcat.

“One of my biggest wins from this race was the level of camaraderie,” says Cove, who snagged two R2AK records this year: fastest singlehanded monohull and fastest monohull under 20 feet. “It’s nice to know that if something goes wrong, we’ve got one another’s backs.”

As an avid offshore and coastal racer on the East Coast, Cove said that the R2AK was the most challenging race he’s ever done. The captain of this year’s first-place winner, Duncan Gladman of Team Malolo, agrees.

“The R2AK has every difficult element,” Gladman says. “You’re constantly navigating. The weather is constantly shifting. And it just gets harder the farther up the course you get.”

Gladman is well-versed in the unpredictable nature of the R2AK. He attempted the race aboard the same trimaran twice before, only to be crushed (literally) by logs. The third time was the charm: His team finished in five days this past June.

On Day 10 of our voyage, we saw the light at the end of the tunnel—or, in this case, the narrow channel that was our exit for Ketchikan. Dall’s porpoises ushered us through the last rolling swells of the Dixon Entrance. Even in my disheveled, hangry-zombie state, it still took all of my willpower not to push the tiller to starboard and head south to Hawaii. I wasn’t quite ready to say goodbye to the rhythm of our days aboard. But we held our course, enticed by hot showers, a real toilet, dry beds and the warm welcome awaiting us.

When we rang the bell at the finish line at 1:03 a.m., the dock was brimming full of fellow racers and well-wishers. I cried happy tears and hugged my teammates.

And then I promptly started planning my next sailing adventure.

Fear the Grim Sweeper

The R2AK committee isn’t playing around. It’s a race, not a leisurely stroll. The trusty sweep boat, affectionately dubbed the “Grim Sweeper,” is on the move as soon as the first racer reaches Ketchikan, or by June 21, whichever comes later. From Port Townsend, it cruises north at about 75 miles a day. If you see it heading your way, you’re out of the race. They’ll collect your tracking device and say hi, but don’t expect a free ride to Ketchikan. They can help you figure out your next steps though. —CW staff

Alaska

Dozens of vehicle accidents reported, Anchorage after-school activities canceled, as snowfall buries Southcentral Alaska

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – Up to a foot of snow has fallen in areas across Southcentral as of Tuesday, with more expected into Wednesday morning.

All sports and after-school activities — except high school basketball and hockey activities — were canceled Tuesday for the Anchorage School District. The decision was made to allow crews to clear school parking lots and manage traffic for snow removal, district officials said.

“These efforts are critical to ensuring schools can safely remain open [Wednesday],” ASD said in a statement.

The Anchorage Police Department’s accident count for the past two days shows there have been 55 car accidents since Monday, as of 9:45 a.m. Tuesday. In addition, there have been 86 vehicles in distress reported by the department.

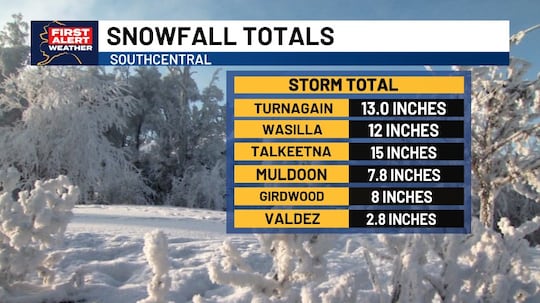

The snowfall — which has brought up to 13 inches along areas of Turnagain Arm and 12 inches in Wasilla — is expected to continue Tuesday, according to latest forecast models. Numerous winter weather alerts are in effect, and inland areas of Southcentral could see winds up to 25 mph, with coastal areas potentially seeing winds over 45 mph.

Some areas of Southcentral could see more than 20 inches of snowfall by Wednesday, with the Anchorage and Eagle River Hillsides, as well as the foothills of the Talkeetna Mountain, among the areas seeing the most snowfall.

See a spelling or grammar error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2026 KTUU. All rights reserved.

Alaska

Yundt Served: Formal Charges Submitted to Alaska Republican Party, Asks for Party Sanction and Censure of Senator Rob Yundt

On January 3, 2026, Districts 27 and 28 of the Alaska Republican Party received formal charges against Senator Rob Yundt pursuant to Article VII of the Alaska Republican Party Rules.

According to the Alaska Republican Party Rules: “Any candidate or elected official may be sanctioned or censured for any of the following

reasons:

(a) Failure to follow the Party Platform.

(b) Engagement in any activities prohibited by or contrary to these rules or RNC Rules.

(c) Failure to carry out or perform the duties of their office.

(d) Engaging in prohibited discrimination.

(e) Forming a majority caucus in which non-Republicans are at least 1/3 or more of the

coalition.

(f) Engaging in other activities that may be reasonably assessed as bringing dishonor to

the ARP, such as commission of a serious crime.”

Party Rules require the signatures of at least 3 registered Republican constituents for official charges to be filed. The formal charges were signed by registered Republican voters and District N constitutions Jerad McClure, Thomas W. Oels, Janice M. Norman, and Manda Gershon.

Yundt is charged with “failure to adhere and uphold the Alaska Republican Party Platform” and “engaging in conduct contrary to the principles and priorities of the Alaska Republican Party Rules.” The constituents request: “Senator Rob Yundt be provided proper notice of the charges and a full and fair opportunity to respond; and that, upon a finding by the required two-thirds (2/3) vote of the District Committees that the charges are valid, the Committees impose the maximum sanctions authorized under Article VII.”

If the Party finds Yundt guilty of the charges, Yundt may be disciplined with formal censure by the Alaska Republican Party, declaration of ineligibility for Party endorsement, withdrawal of political support, prohibition from participating in certain Party activities, and official and public declaration that Yundt’s conduct and voting record contradict the Party’s values and priorities.

Reasons for the charges are based on Yundt’s active support of House Bill 57, Senate Bill 113, and Senate Bill 92. Constituents who filed the charges argue that HB 57 opposes the Alaska Republican Party Platform by “expanding government surveillance and dramatically increasing education spending;” that SB 113 opposes the Party’s Platform by “impos[ing] new tax burdens on Alaskan consumers and small businesses;” and that SB 92 opposes the Party by “proposing a targeted 9.2% tax on major private-sector energy producer supplying natural gas to Southcentral Alaska.” Although the filed charges state that SB 92 proposes a 9.2% tax, the bill actually proposes a 9.4% tax on income from oil and gas production and transportation.

Many Alaskan conservatives have expressed frustration with Senator Yundt’s legislative decisions. Some, like Marcy Sowers, consider Yundt more like “a tax-loving social justice warrior” than a conservative.

Related

Alaska

Pilot of Alaska flight that lost door plug over Portland sues Boeing, claims company blamed him

The Alaska Airlines captain who piloted the Boeing 737 Max that lost a door plug over Portland two years ago is suing the plane’s manufacturer, alleging that the company has tried to shift blame to him to shield its own negligence.

The $10 million suit — filed in Multnomah County Circuit Court on Tuesday on behalf of captain Brandon Fisher — stems from the dramatic Jan. 5, 2024 mid-air depressurization of Flight 1282, when a door plug in the 26th row flew off six minutes after take off, creating a 2-by-4-foot hole in the plane that forced Fisher and co-pilot Emily Wiprud to perform an emergency landing back at PDX.

None of the 171 passengers or six crew members on board was seriously injured, but some aviation medical experts said that the consequences could have been “catastrophic” had the incident happened at a higher altitude.

Fisher’s lawsuit is the latest in a series filed against Boeing, including dozens from Flight 1282 passengers. It also names Spirit AeroSystems, a subcontractor that worked on the plane.

The lawsuit blames the incident on quality control issues with the door plug. It argues that Boeing caught five misinstalled rivets in the panel, and that Spirit employees painted over the rivets instead of reinstalling them correctly. Boeing inspectors caught the discrepancy again, the complaint alleges, but when employees finally reopened the panel to fix the rivets, they didn’t reattach four bolts that secured the door panel.

The complaint’s allegations that Boeing employees failed to secure the bolts is in line with a National Transportation Safety Board investigation that came to the conclusion that the bolts hadn’t been replaced.

Despite these internal issues, Fisher claims Boeing deliberately shifted blame towards him and his first officer.

Lawyers for Boeing in an earlier lawsuit wrote that the company wasn’t responsible for the incident because the plane had been “improperly maintained or misused by persons and/or entities other than Boeing.”

Fisher’s complaint alleges that the company’s statement was intended to “paint him as the scapegoat for Boeing’s numerous failures.”

“Instead of praising Captain Fisher’s bravery, Boeing inexplicably impugned the reputations of the pilots,” the lawsuit says.

As a result, Fisher has been scrutinized for his role in the incident, the lawsuit alleges, and named in two lawsuits by passengers.

Spokespeople for Boeing and Spirit AeroSystems declined to comment on the lawsuit.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHamas builds new terror regime in Gaza, recruiting teens amid problematic election

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFor those who help the poor, 2025 goes down as a year of chaos

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoInstacart ends AI pricing test that charged shoppers different prices for the same items

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoDid holiday stress wreak havoc on your gut? Doctors say 6 simple tips can help

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoChatGPT’s GPT-5.2 is here, and it feels rushed

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoThe biggest losers of 2025: Who fell flat as the year closed

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoWe Asked for Environmental Fixes in Your State. You Sent In Thousands.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoA tale of two Ralphs — Lauren and the supermarket — shows the reality of a K-shaped economy