Lifestyle

10 biographies and memoirs for the nonfiction reader in your life

There’s one in every family — that uncle or sister-in-law who only reads nonfiction. As you seek out the perfect read for your loved ones this year, we can help you find beautifully told true stories. There are more than 50 biographies and memoirs featured in Books We Love, NPR’s annual year-end reading guide. Check them all out here, or browse a sampling, below.

Consent: A Memoir by Jill Ciment

After the death of her husband of nearly 50 years, Jill Ciment reconsiders their relationship, which began when she was 17 and he was her much older, married drawing instructor. She first wrote about their early years together in Half a Life, when she was in her 40s and he was in his 70s. In Consent, she scrutinizes and amplifies that account in light of the #MeToo movement and changing social attitudes. Did she have the agency to consent? Was he a letch? Was she a vixen? How could she have known as a teenager that he was the love of her life? — Heller McAlpin, book critic

A Fatal Inheritance: How a Family Misfortune Revealed a Deadly Medical Mystery by Lawrence Ingrassia

In 1968, when journalist Lawrence Ingrassia was 15, his mother died of breast cancer at age 42. “It was tragic, but what was there to say?” he writes. Ingrassia couldn’t know then that in the decades to come, his three siblings would each die from a different kind of cancer and that a nephew would too. In A Fatal Inheritance, Ingrassia movingly intertwines his family’s oncological experiences with the winding story of how researchers worked to uncover the roles that heritable genetic mutations play in cancer risk. — Kristin Martin, book critic

Gather Me: A Memoir in Praise of the Books That Saved Me by Glory Edim

Tenderly written, Glory Edim’s Gather Me is a beautiful memoir that serves as a powerful testament to resilience. It pays tribute to the art of community building from someone whose career and identity are deeply rooted in literature. Edim, founder of Well-Read Black Girl, thoughtfully navigates her emotionally complex life, highlighting the books and authors that have shaped her journey. The chapter about Nikki Giovanni’s work – Edim’s spiritual exploration through it and the solace it brought her – is particularly poignant. Overall, it is an emotional narrative about family bonds and a meaningful gift to her community. — Keishel Williams, book critic

Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder by Salman Rushdie

For much of his adult life, Salman Rushdie has lived beneath a shadow – he’s as famous for his novels as he is for being the target of a fatwa. But in 2022, that threat went from theoretical to very real when Rushdie was stabbed repeatedly at a literary conference. That attack resulted in multiple long-term health issues, including blindness in his right eye. You might expect Rushdie’s memoir detailing the attack and its aftermath to be somewhat grim. And it is. But it’s also in turn warm, vulnerable, acerbic and, surprisingly, very funny. — Leah Donnella, senior editor, Code Switch

Life After Power: Seven Presidents and Their Search for Purpose Beyond the White House by Jared Cohen

The American presidency is viewed as the most powerful position in the world. What happens when the job ends? History is often surprising. Not everyone found the role to be the most fulfilling one they ever had. Jared Cohen looks at some fascinating case studies that back that up. John Quincy Adams and William Howard Taft found greater joy in other branches of government: Congress and the Supreme Court. George Bush enjoys his private life and art studio. Life after power can be much more rewarding. — Edith Chapin, senior vice president and editor in chief

Little, Brown and Company

The Mango Tree: A Memoir of Fruit, Florida, and Felony by Annabelle Tometich

This family memoir begins with a courtroom scene like no other. After a night in jail, Annabelle Tometich’s mom is charged with firing at a man who, she says, was stealing mangoes from the tree in her front yard. Tometich then hits rewind, taking readers back through her Fort Myers, Fla., childhood – with her Filipino American mom and white dad, a couple whose personality differences do not make them stronger together. The writing is both jewel-like and effortless, and Tometich’s memories – some mundane, some extraordinary – are mesmerizing. — Shannon Rhoades, senior editor, Weekend Edition

Little, Brown and Company

My Beloved Monster: Masha, the Half-Wild Rescue Cat Who Rescued Me by Caleb Carr

This unusual and beautiful “meow-moir” by The Alienist author and military historian Caleb Carr – the last book he wrote before dying of cancer at age 68 this year – explores the author’s lifelong affinity for cats and his particular relationship with one enormous, fluffy Siberian named Masha. Masha and the writer enjoyed 17 years of adventures together, mostly in and around their rugged rural home in upstate New York. The book chronicles their mutual zest for life and their struggles through illness and financial woes. Even though this is a book for cat lovers, it’s really for everyone: It explores, with somber pathos and wry humor, how we form attachments in life and how they keep us going through it all. — Chloe Veltman, correspondent, Culture Desk

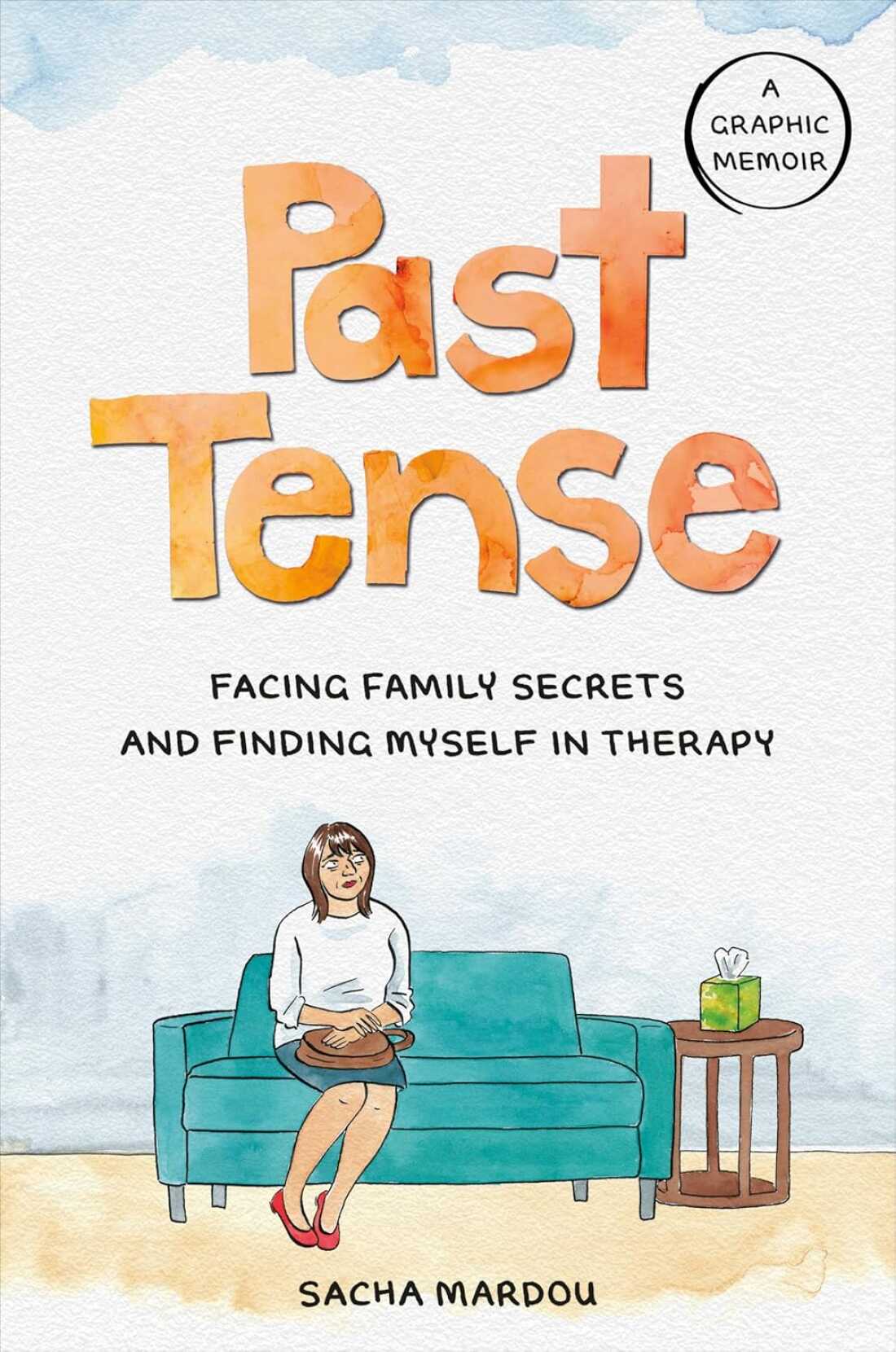

Past Tense: Facing Family Secrets and Finding Myself in Therapy by Sacha Mardou

British cartoonist Sacha Mardou began posting her highly readable comics – about her experiences going to therapy when her daughter was young – on social media. Past Tense chronicles this story – the many steps that led Mardou to an earnest bridging of the past, her family’s history, into the present. Somewhere between Allie Brosh’s Hyperbole and a Half and Stephanie Foo’s What My Bones Know, Mardou’s brightly tinted, clear-eyed comics reveal how active self-reflection – combined with art, storytelling and professional supports – can powerfully reshape a person’s sense of self and community. — Tahneer Oksman, writer, professor and cultural critic

Patriot: A Memoir by Alexei Navalny

Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny died in an Arctic Russian penal colony in February. But even in death, he continues his fight against President Vladimir Putin. This posthumous memoir has two sections: The first half is a traditional narrative, beginning with a true crime story when Navalny is poisoned with a nerve agent on a flight from Siberia in 2020. Halfway through, the book pivots to become his prison diary. Through even the darkest episodes, Navalny’s sunniness and humor shine through – whether he’s describing an episode of Rick and Morty that he left unfinished when he collapsed on that flight, or taking joy in the indulgence of bread and butter that he only ate on Sunday mornings behind bars. — Ari Shapiro, host, All Things Considered

In straightforward and affecting prose, Deborah Jackson Taffa writes about being brought up by a Quechan (Yuma) and Laguna Pueblo father and a Catholic Latina mother, both on and off the Yuma reservation. Although her parents were united in their approach to maintaining a family, their attitudes toward the world diverged in other ways, and Taffa received mixed messages about her Indigeneity, her proximity to whiteness and how she was meant to carry herself. As a teenager, she began to experience anger at the injustices her people were subjected to and, at the same time, began to learn that all change is sacred. — Ilana Masadbook, critic and author of All My Mother’s Lovers

This is just a fraction of the 350+ titles we included in Books We Love this year. Click here to check out this year’s titles, or browse nearly 4,000 books from the last 12 years.

Lifestyle

Mundane, magic, maybe both — a new book explores ‘The Writer’s Room’

There’s a three-story house in Baltimore that looks a bit imposing. You walk up the stone steps before even getting up to the porch, and then you enter the door and you’re greeted with a glass case of literary awards. It’s The Clifton House, formerly home of Lucille Clifton.

The National Book Award-winning poet lived there with her husband, Fred, starting in 1967 until the bank foreclosed on the house in 1980. Clifton’s daughter, Sidney Clifton, has since revived the house and turned it into a cultural hub, hosting artists, readings, workshops and more. But even during a February visit, in the mid-afternoon with no organized events on, the house feels full.

The corner of Lucille Clifton’s bedroom, where she would wake up and write in the mornings

Andrew Limbong/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Limbong/NPR

“There’s a presence here,” Clifton House Executive Director Joël Díaz told me. “There’s a presence here that sits at attention.”

Sometimes, rooms where famous writers worked can be places of ineffable magic. Other times, they can just be rooms.

Princeton University Press

Katie da Cunha Lewin is the author of the new book, The Writer’s Room: The Hidden Worlds That Shape the Books We Love, which explores the appeal of these rooms. Lewin is a big Virginia Woolf fan, and the very first place Lewin visited working on the book was Monk’s House — Woolf’s summer home in Sussex, England. On the way there, there were dreams of seeing Woolf’s desk, of retracing Woolf’s steps and imagining what her creative process would feel like. It turned out to be a bit of a disappointment for Lewin — everything interesting was behind glass, she said. Still, in the book Lewin writes about how she took a picture of the room and saved it on her phone, going back to check it and re-check it, “in the hope it would allow me some of its magic.”

Let’s be real, writing is a little boring. Unlike a band on fire in the recording studio, or a painter possessed in their studio, the visual image of a writer sitting at a desk click-clacking away at a keyboard or scribbling on a piece of paper isn’t particularly exciting. And yet, the myth of the writer’s room continues to enrapture us. You can head to Massachusetts to see where Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women. Or go down to Florida to visit the home of Zora Neale Hurston. Or book a stay at the Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald Museum in Alabama, where the famous couple lived for a time. But what, exactly, is the draw?

Lewin said in an interview that whenever she was at a book event or an author reading, an audience question about the writer’s writing space came up. And yes, some of this is basic fan-driven curiosity. But also “it started to occur to me that it was a central mystery about writing, as if writing is a magic thing that just happens rather than actually labor,” she said.

In a lot of ways, the book is a debunking of the myths we’re presented about writers in their rooms. She writes about the types of writers who couldn’t lock themselves in an office for hours on end, and instead had to find moments in-between to work on their art. She covers the writers who make a big show of their rooms, as a way to seem more writerly. She writes about writers who have had their homes and rooms preserved, versus the ones whose rooms have been lost to time and new real estate developments. The central argument of the book is that there is no magic formula to writing — that there is no daily to-do list to follow, no just-right office chair to buy in order to become a writer. You just have to write.

Lifestyle

Bruce Johnston Retiring From The Beach Boys After 61 Years

Bruce Johnston

I’m Riding My Last Wave With The Beach Boys

Published

Bruce Johnston is riding off into the California sunset … at least for now.

The Beach Boys legend announced Wednesday he’s stepping away from touring after six decades with the iconic band. The 83-year-old revealed in a statement to Rolling Stone he’s hanging up his touring hat to focus on what he calls part three of his long music career.

“It’s time for Part Three of my lengthy musical career!” Johnston said. “I can write songs forever, and wait until you hear what’s coming!!! As my major talent beyond singing is songwriting, now is the time to get serious again.”

Johnston famously stepped in for co-founder Brian Wilson in 1965 for live performances, becoming a staple of the Beach Boys’ touring lineup ever since. Now, he says he’s shifting gears toward songwriting and even some speaking engagements … with occasional touring member John Stamos helping him craft what he’ll talk about onstage.

“I might even sing ‘Disney Girls’ & ‘I Write The Songs!!’” he teased.

But don’t call it a full-on farewell tour just yet. Johnston made it clear he’s not shutting the door completely, saying he’s excited to reunite with the band for special occasions, including their upcoming July 2-4 shows at the Hollywood Bowl as part of the Beach Boys’ 2026 tour. The run celebrates both the 60th anniversary of “Pet Sounds” and America’s 250th birthday.

“This isn’t goodbye, it’s see you soon,” he wrote. “I am forever grateful to be a part of the Beach Boys musical legacy.”

Lifestyle

On the brink of death, a woman is saved by a stranger and his family

In 1982, Jean Muenchrath was injured in a mountaineering accident and on the brink of death when a stranger and his family went out of their way to save her life.

Jean Muenchrath

hide caption

toggle caption

Jean Muenchrath

In early May 1982, Jean Muenchrath and her boyfriend set out on a mountaineering trip in the Sierra Nevada, a mountain range in California. They had done many backcountry trips in the area before, so the terrain was somewhat familiar to both of them. But after they reached one of the summits, a violent storm swept in. It began to snow heavily, and soon the pair was engulfed in a blizzard, with thunder and lightning reverberating around them.

“Getting struck and killed by lightning was a real possibility since we were the highest thing around for miles and lightning was striking all around us,” Muenchrath said.

To reach safer ground, they decided to abandon their plan of taking a trail back. Instead, using their ice axes, they climbed down the face of the mountain through steep and icy snow chutes.

They were both skilled at this type of descent, but at one particularly difficult part of the route, Muenchrath slipped and tumbled over 100 feet down the rocky mountain face. She barely survived the fall and suffered life-threatening injuries.

This was before cellular or satellite phones, so calling for help wasn’t an option. The couple was forced to hike through deep snow back to the trailhead. Once they arrived, Muenchrath collapsed in the parking lot. It had been five days since she’d fallen.

”My clothes were bloody. I had multiple fractures in my spine and pelvis, a head injury and gangrene from a deep wound,” Muenchrath said.

Not long after they reached the trailhead parking lot, a car pulled in. A man was driving, with his wife in the passenger seat and their baby in the back. As soon as the man saw Muenchrath’s condition, he ran over to help.

”He gently stroked my head, and he held my face [and] reassured me by saying something like, ‘You’re going to be OK now. I’ll be right back to get you,’” Muenchrath remembered.

For the first time in days, her panic began to lift.

“My unsung hero gave me hope that I’d reach a hospital and I’d survive. He took away my fears.”

Within a few minutes, the man had unpacked his car. His wife agreed to stay back in the parking lot with their baby in order to make room for Muenchrath, her boyfriend and their backpacks.

The man drove them to a nearby town so that the couple could get medical treatment.

“I remember looking into the eyes of my unsung hero as he carried me into the emergency room in Lone Pine, California. I was so weak, I couldn’t find the words to express the gratitude I felt in my heart.”

The gratitude she felt that day only grew. Now, nearly 45 years later, she still thinks about the man and his family.

”He gave me the gift of allowing me to live my life and my dreams,” Muenchrath said.

At some point along the way, the man gave Muenchrath his contact information. But in the chaos of the day, she lost it and has never been able to find him.

”If I knew where my unsung hero was today, I would fly across the country to meet him again. I’d hug him, buy him a meal and tell him how much he continues to mean to me by saving my life. Wherever you are, I say thank you from the depths of my being.”

My Unsung Hero is also a podcast — new episodes are released every Tuesday. To share the story of your unsung hero with the Hidden Brain team, record a voice memo on your phone and send it to myunsunghero@hiddenbrain.org.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Wisconsin3 days ago

Wisconsin3 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Florida4 days ago

Florida4 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Oregon5 days ago

Oregon5 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling