Lifestyle

Downsizing, decluttering, Swedish death cleaning — why we're obsessed with clearing out our stuff

When I asked my mother what she might like for her birthday this year, she quickly texted back: Nothing. We are downsizing.

My parents already live in a small house — a former fishing cabin on the edge of a lake. Our family moved a few times when my brothers and I were growing up, our childhood belongings pared down at each step. My parents relocated after we graduated from college, stripping their belongings down further and shipping what furniture was left to each of us kids. I got the Sellers Hoosier, a wooden hutch with a built-in tin flour bin and a metal bread kneading shelf, now more than 100 years old, that my great-grandmother used to bake on.

I wondered what was left for them to downsize. And then it hit me: Were they doing the Swedish death clean? “Döstädning: The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning” is the bestselling book that sparked a TV show and popularized a decluttering technique that has people clean up their belongings before they die, so their friends and family won’t have to. My mother will be 80 this year, my father 82 — was there something they weren’t telling me?

It turned out that my parents hadn’t seen the show or read the book. The real problem was that they had just inherited a bunch of “stuff” from my aunt, who has dementia and was moving into assisted living. My mom told me about all the things my aunt had treasured and saved that now sat in cardboard boxes: plates and linen dish towels commemorating the British Royals; Hummel figurines (and some fakes); newspaper clippings. There were also letters, photos, notes and journals. Birthday cards. Those personal items we save, private and special only to us. Our “stuff.” My aunt had never intended for anyone else to see it or have to deal with it.

My mother didn’t think it was appropriate to throw any of it away, not while my aunt was still alive. “She asked that some of the Princess Diana things be sent to you,” Mom confessed. “But,” she whispered, “I don’t think you’d want it.” She’s right, I don’t, but the larger question is: Who does?

The idea of döstädning (and the fact that my aunt clearly didn’t get around to it) made me think about all the stuff I’ve collected over the years. When I moved from New York to Los Angeles more than 20 years ago, I couldn’t afford to ship most of my books, so I sent only the most precious, signed editions I had. I also sent the journals I’d written in for years, stuffed with the small details of my life in New York City. What I wore on a first date. A promotion. An unrequited crush. I was moving to Los Angeles for love, but I couldn’t part with these chronicles of all my previous relationships.

Now those journals live in the garage of my family’s Los Feliz house. I know exactly which plastic bin they’re in, even though I haven’t read them since I left New York. If I were to die tomorrow, how would I feel about someone else reading them — my parents, my son, my husband? And if I don’t want anyone reading them after I’m gone, why have I kept them?

This led me to ask my friends and family: Is there anything that you would want automatically destroyed after your death, before your loved ones found it? Most of the answers revolved around sex: naked photos, sex toys, pornography, dirty notes and sexts. Other answers were more comical: A pot stash they didn’t want kids to find; specifically, weed butter in the freezer. The secret family in New Jersey (I think he was joking).

Some people revealed that they had pacts with a friend or relative to destroy certain items after their death. I loved the idea of a trusted friend tossing all my buried secrets, until I remembered what happened to Franz Kafka. His friend and literary executor, Max Brod, had been entrusted to burn all of Kafka’s letters and manuscripts after his death — a wish Kafka put in writing, even though Brod told him he wouldn’t do it. Indeed, Brod published the material, and we would not have “The Trial,” “The Castle” or other great works had he followed Kafka’s instructions.

Did Brod have the right to overrule his friend? Perhaps it’s better to ask if Kafka had the right to ask that the manuscripts be destroyed. As an artist, do you owe the world your work, even after death?

My friend Cecil, a novelist, says: “As artists, it’s our gig to keep the embarrassing things that inspire us around. We are complex, and hopefully everyone gets that.” She says her journals would make a “boring read” — but if she asked me to destroy all her works after her death and I found some beautiful piece of writing among them, I would be torn about how to proceed.

Even though I’ve published a memoir and works of fiction that allow readers a glimpse into my life, I still have parts of myself that I don’t want anyone to see. In this age of over-sharing, talking about what I would want wiped out after my death has given me a better understanding of döstädning and its appeal. It’s less about saving our families from having to do the cleaning-up work, and more about applying some small measure of control over how we are remembered by those we loved. Perhaps it’s also a nudge to live a life worthy of remembering — sex toys and all — while we still can.

Cylin Busby is an author and screenwriter. Her latest book is “The Bookstore Cat.”

Lifestyle

Ilia Malinin’s Olympic backflip made history. But he’s not the first to do it

Ilia Malinin lands a backflip in his free skate in the team event on Sunday. His high score pushed Team USA to the top of the podium.

Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

Want more Olympics updates? Subscribe here to get our newsletter, Rachel Goes to the Games, delivered to your inbox for a behind-the-scenes look at the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics.

MILAN — Ilia Malinin’s skyward jumps have earned him the nickname the “Quad God,” but it’s his backflip that everyone seems to be talking about.

The U.S. figure skater performed the move in his first two programs on Olympic ice, landing the latter on a single blade and sending the arena into a frenzy.

“It’s honestly such an incredible roar-feeling in the environment — once I do that backflip everyone is like screaming for joy and they’re just out of control,” Malinin said. “The backflip is something that I’m sure a lot of people know the basics of … so I think just having that really can bring in the non-figure skating crowd as well.”

Malinin, who trained in gymnastics when he was younger, first debuted his backflip in competition in 2024 — the year the sport’s governing body lifted its ban on the move.

His moves in Milan aren’t just awe-inspiring, but historic: Malinin is the first person to legally land a backflip at the Olympics in five decades.

It was controversial from the start

Terry Kubicka, also an American, became the first skater to land a backflip in international competition at the 1976 Innsbruck Olympics.

“There was a lot of controversy leading up to the Olympics, because I did it for the first time a month before at the U.S. Championships,” Kubicka told U.S. Figure Skating decades later. “At the time, there was no ruling on as how it would be [scored] and the feedback that I got was that judges did not really see it as a pro or con because they didn’t know how to judge it.”

The International Skating Union, the sport’s governing body, banned the backflip the following year, in part because of the level of danger and in part because it violated the principle of jumps landing on one skate.

But the backflip didn’t totally disappear. Some elite skaters — including 1984 gold medalist Scott Hamilton — continued landing the move in non-competitive settings, like exhibition shows.

And one skater even dared to bring a banned backflip on to Olympic ice.

Surya Bonaly of France performed an illegal backflip at the 1998 Olympics, figuring if she wasn’t going to medal she could at least make history.

Eric Feferberg/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Eric Feferberg/AFP via Getty Images

France’s Surya Bonaly landed a backflip on one blade at the 1998 Nagano Games, even while injured, in what is widely considered a brave act of defiance.

She knew she couldn’t get the scores she needed to win, but was determined to make her mark on history anyway. It did cost her points but it also cemented her trailblazing legacy, especially as a Black athlete in sport with a relative lack of diversity.

“I appreciate more and I feel more proud of myself now, today, than years ago for when I did it,” Bonaly said in 2020.

The backflip comes back

In recent years, a handful of skaters — including U.S. defending Olympic champion Nathan Chen — have backflipped at exhibition galas, much to viewers’ delight.

France’s Adam Siao Him Fa pictured in October 2025, once the backflip was legal. He performed it in competition the year before, when it was not.

Jean-Francois Monier/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jean-Francois Monier/AFP via Getty Images

The move reached an even bigger crowd at European Championships in 2024, when French skater Adam Siao Him Fa landed one in his free skate program, enjoying such a comfortable lead that the deduction wouldn’t matter. He did it again at the World Championships the same year, and still walked away with a bronze medal.

In a full-circle twist, Kubicka — the first to land an Olympic backflip — was a member of the technical panel that watched Siao Him Fa do it at worlds, and gave him the requisite two-point deduction, almost exactly 50 years later.

Later that year, the International Skating Union officially reversed its backflip ban starting in the 2024-2025 season, explaining on its meeting agenda that “somersault type jumps are very spectacular and nowadays it is not logical anymore to include them as illegal movements.”

The backflip can no longer lose a skater points, but it doesn’t count toward their technical score either (it’s not a required move). It could, however, boost a skater’s artistic score and confidence.

“Oh, that’s my favorite part,” U.S. competitive skater Will Annis, 21, said after landing a backflip at the U.S. Figure Skating Championships in January. “Every time the crowd goes crazy for it, and it’s actually easier than everything else I do, so it’s really fun.”

His definition of “easier” is that “you can be a little off and still land it” on two feet.

Annis told NPR he had long been able to do a backflip on the ground, but didn’t bother learning how to bring it to the ice until he saw Siao Him Fa do it. He was inspired by that protest but didn’t have time to rebel himself: He says the ban was lifted just days before his first competition.

Lifestyle

Jeanette Marantos, L.A. Times plants reporter, dies at 70

Jeanette Marantos, a stalwart Features reporter for the Los Angeles Times, died Saturday following an emergency heart issue. She was 70.

Marantos was key to the success of The Times’ plants coverage, making waterwise native plants a cornerstone of her reporting as drought and climate change worsened in California. She spotlighted people turning their yards into native plant oases and beautifying public spaces. She also wrote about people saving native flora and fauna, from mountain lions in need of a freeway crossing to endangered butterflies and tiny native bees. Her last assignment Friday was covering the California Native Plant Society’s conference in Riverside.

“She was the most loving person I ever met, probably to a fault in some cases. If she knew you and you were a part of her life, she was fiercely loyal always,” said her son, Sascha Smith.

His brother, Dimitri Smith, echoed his sentiment, recalling when he was in school that his mother would offer rides home to other students when they didn’t have one. “Above all else, she was genuinely the most caring person I’ve ever met in my life,” Dimitri Smith said.

Marantos, who was born on March 13, 1955, grew up in Riverside and remembered her parents doting on their 3,000-square-foot lawn. As California’s water crisis worsened, recalling the constant swish of sprinklers throughout her childhood piqued her interest in native plants.

“That was the California landscape of my youth. In retrospect, it feels like a pipe dream, given the reality of this region’s limited water and propensity for drought … a lovely memory that is no longer sustainable today,” she wrote.

Marantos also covered the effects of last year’s L.A. County wildfires on soil and gardens, the fate of Altadena’s Christmas Tree Lane after the Eaton fire, the construction of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, a project that kicked off with a hyperlocal nursery, how L.A. gardeners were reacting to immigration raids, and the rise of human composting. Known formally as natural organic reduction, Marantos’ remains will undergo this process to become soil, her sons said.

Jeanette Marantos appears at the L.A. Times Plants booth at the paper’s Festival of Books on April 21, 2024.

(Maryanne Pittman)

In her role at work, she wrote the beloved L.A. Times Plants newsletter, her latest focusing on the resiliency of plants in burn areas. She also launched the popular L.A. Times Plants booth at the paper’s Festival of Books, working with the Theodore Payne Foundation, a nonprofit education center and nursery focused on native plants, and the California Native Plant Society to educate visitors about native plants. She drove the initiative to give away sunflower seed packets at last year’s booth because the sturdy plants are known to extract lead, an idea that came to her as she tested contaminated soil in burn zones.

She “was a one-of-a-kind voice for plants and the people who care about them. Through her writing, she imbued others with her infectious enthusiasm for the natural world — a gift to all of us that will continue to resonate,” according to a statement from the Theodore Payne Foundation. “Her visits to the nursery, her thoughtful conversations, and her wholehearted engagement brought laughter and insight into every interaction.”

Marantos was a dedicated reporter — she’d drive 60 miles to get an answer when no one was picking up the phone — but also devoted to her family. She cared for her husband, Steven B. Smith, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2011 and died in 2021, providing readers with tips from their experiences. She spoke often of her sons and grandchildren and her dogs. She opened her December Plants newsletter, about a mother-son duo’s seed bomb project, by sharing that she had recently welcomed another “perfect” granddaughter.

“Plus I got to listen to my other perfect granddaughter read her first book and help her plant her first sunflower,” she wrote.

Sascha Smith recalled one of the last things Marantos said before going into emergency surgery Friday was sorry to his daughter Naomi, 6, for missing her birthday Sunday.

Gardens full of buckwheat, sage, vegetables, roses and treasured sweet peas surround her Ventura home. Her father, an Air Force veteran and son of Greek immigrants, introduced her to “the miracle of seeds” and to the delicious perfume of sweet peas. She remembered trailing behind her grandmother cutting roses in her garden, lugging bucketfuls of flowers and inhaling the sweetness. She added native plants to her garden because yes, they helped save water, butterflies and bees, but also because she loved their fragrance.

“These lean, scrappy plants are rarely as showy as their ornamental cousins, but when it comes to fragrance, they win every award, hands down,” she wrote.

It wasn’t just aesthetics and aroma that inspired Marantos to garden. It was the acts of digging, weeding, watching something grow and sharing the abundance with others. “On my worst days, my garden was a reason to get out of bed in the morning, and the one thing that made me smile,” she wrote.

Jeanette Marantos appears on “Los Angeles Times Today” in June 2024 with host Lisa McRee.

(L.A. Times Today)

Marantos tended to her garden like she tended to her friends. She often brought her friends along on reporting trips, from hiking up Los Angeles’ steepest staircases and visiting wildflower viewing areas to convincing one who flew in to Los Angeles from Washington state to spend a weekend volunteering at The Times’ Plants booth at the Festival of Books.

Marantos lived in central Washington for more than 20 years, working as a reporter at the Wenatchee World Newspaper and as a teacher at Wenatchee High School. She also worked for a program focused on getting at-risk middle school youth into college. “So many students … the trajectory of their lives is very different because she believed in them,” Dimitri Smith said.

Working as a community volunteer, she was also integral in developing a sculpture garden in downtown Wenatchee, Dimitri Smith said. “Growing up, I didn’t know how special that was. I didn’t know how unique that was. She wanted to be engaged in the community and make a difference always,” he said.

Marantos wrote personal finance stories for The Times from 1999 to 2002. She moved from Washington back to Southern California in her 50s to restart her journalism career, at one point interning with KPCC, now known as LAist, Dimitri Smith said. In 2015, she returned to The Times to write for the Homicide Report. A year later she started contributing to the Saturday section’s gardening coverage, which she would work on full time in 2020 when it relaunched as L.A. Times Plants. She described the two disparate beats as a way of staying balanced, her yin and yang.

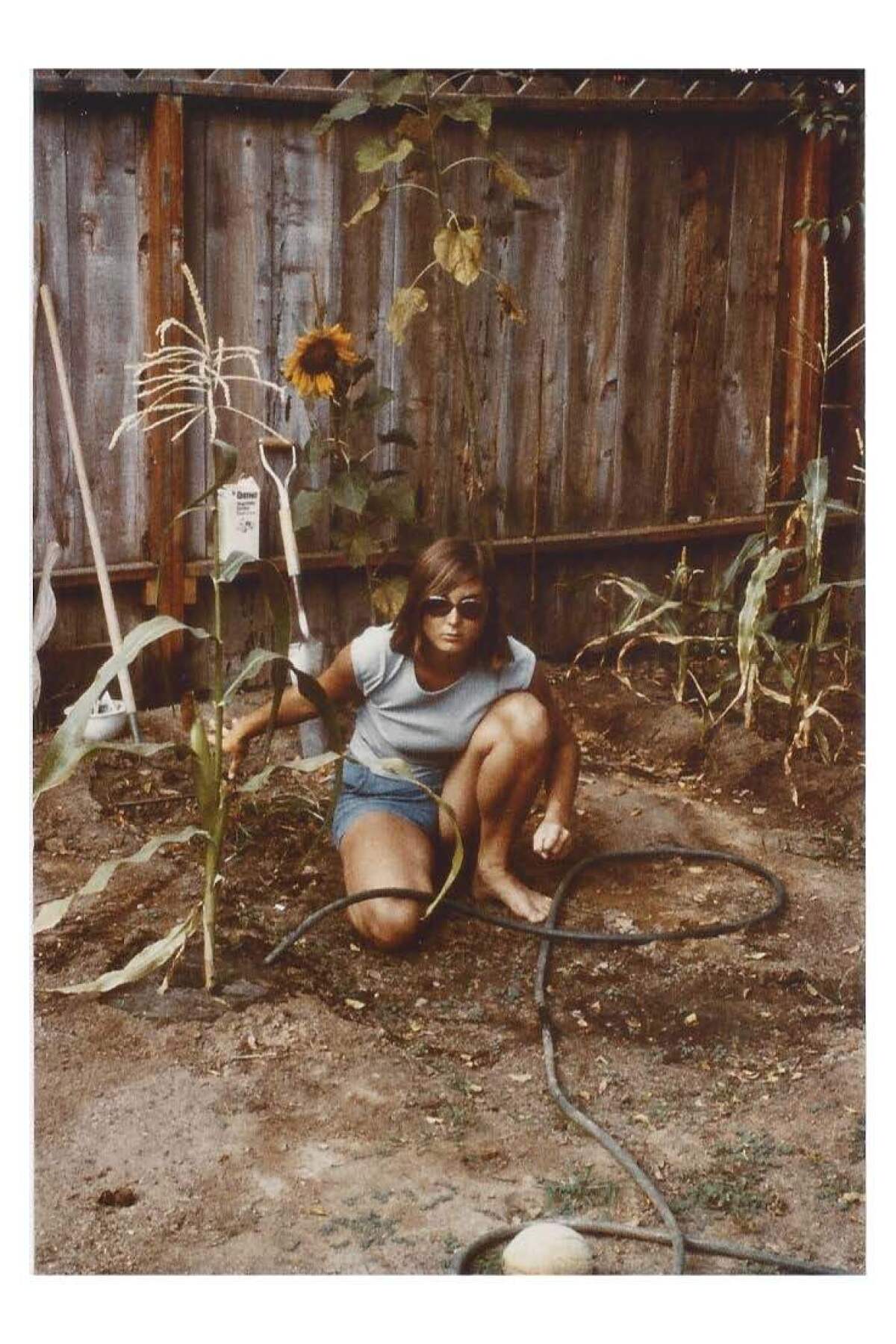

Jeanette Marantos, shown around 1975, tries to grow her first garden.

(Steven B. Smith)

“Going from homicide to gardening might seem unusual, or maybe even a step away from the action. But not for Jeanette. First off, she personally loved gardening. … So the assignment was kinda like telling a kid to cover the candy beat,” said Rene Lynch, a former Times editor who hired Marantos on the plants beat. “But also, Jeanette was a true journalist, which means she had an innate curiosity about everything.”

Learning to garden took dedication. Marantos described her first attempt in her 20s as disastrous; her tomato plants grew more leaves than fruit, her sunflowers were sad, not hearty. She thought of her explainers on various plant topics as her ongoing education.

“Our family is completely grief-stricken and shocked over her loss. We’re going to have a very, very difficult time living without her,” said her brother, Tom Marantos.

She is survived by her son Sascha Smith and his daughter Naomi Smith; son Dimitri Smith, his wife Molly Smith and their daughter Charlie Smith; her brother Tom Marantos and his partner Rafael Lopez; her sisters Lisa and Alexis Marantos; and her best friends, who were like family, Leslie Marshall and Theresa Samuelsen.

Lifestyle

We unpack Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show : Pop Culture Happy Hour

Bad Bunny performs onstage during the Super Bowl halftime show at Levi’s Stadium.

Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images

At the Super Bowl halftime show, Bad Bunny put on an endlessly rewatchable performance. It featured Lady Gaga, Ricky Martin, and a real wedding. But it didn’t shy away from this political moment, and Bad Bunny’s place in the culture wars.

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old rider dies following incident at northwest Indiana BMX park

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoTV star fisherman, crew all presumed dead after boat sinks off Massachusetts coast

-

Tennessee1 week ago

Tennessee1 week agoUPDATE: Ohio woman charged in shooting death of West TN deputy

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old boy dies in BMX accident, officials, Steel Wheels BMX says

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoTrump unveils new rendering of sprawling White House ballroom project

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

San Francisco, CA5 days ago

San Francisco, CA5 days agoExclusive | Super Bowl 2026: Guide to the hottest events, concerts and parties happening in San Francisco

-

Texas1 week ago

Texas1 week agoLive results: Texas state Senate runoff