Northeast

Roundup weed killer cancer lawsuits keep mounting as Pennsylvania man is awarded $78 million

A Pennsylvania man was awarded $78 million after filing a lawsuit saying he developed cancer from using the weed killer Roundup.

William Melissen, 51, said he was diagnosed in 2020 with a blood cancer called Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and a type of leukemia, which he argued was because of his exposure to chemicals in the weed killer, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

It’s the latest in a string of lawsuits against the company that’s already reached nearly $11 billion in settlements so far, and thousands of more lawsuits are pending.

Melissen claims he used the product frequently for nearly 30 years between 1992 and 2020. He sued agricultural giant Monsanto, which makes Roundup, and its German parent company, Bayer, in 2021.

PENNSYLVANIA HIGH SCHOOL FOOTBALL PLAYER COLLAPSES DURING GAME FOLLOWING HARD HIT TO HELMET

William Melissen, 51, was awarded $78 million after filing a lawsuit saying he developed cancer from using the weed killer Roundup. (Getty Images)

A Philadelphia jury ruled on Thursday that the man’s cancer was caused by Glyphosate, which is the key ingredient in Roundup. The jury awarded him $3 million dollars in compensatory damages and $75 million in punitive damages.

Monsanto said in a statement that it disagrees with the jury’s verdict and that evidence does not support the claim that Roundup causes cancer. The company also said that trial errors provided the company with strong grounds for appeal.

The alleged errors include that the case was not dismissed after three judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled in August that Pennsylvania state law cannot require a more expansive pesticide warning label than the one approved by the Environmental Protection Agency.

William Melissen said he was diagnosed in 2020 with a blood cancer called Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. (Getty Images)

During the trial, Monsanto’s attorney, Bart Williams, presented to the jury transcripts from testimony by Melissen and his treating physician showing that his cancer is in remission, and that he was treated with a five-day round of chemotherapy.

Melissen’s lawsuit is one of thousands of cases nationally in which people who developed cancer accuse Monsanto of failing to include adequate warnings about its weed killer product.

VILLANOVA UNIVERSITY STUDENT RAPED BY UBER DRIVER IN DORM ROOM, POLICE SAY

A Philadelphia jury ruled that the man’s cancer was caused by Glyphosate, which is the key ingredient in Roundup. (Paul Hennessy/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Monsanto has reached settlements in nearly 100,000 Roundup lawsuits in which it paid roughly $11 billion. Monsanto estimates that 54,000 active Roundup lawsuits still remain.

“This is one more jury that recognized the outrageous conduct of Monsanto for 50 years,” Melissen’s attorney Tom Kline told the Philadelphia Inquirer after Thursday’s verdict.

Read the full article from Here

Northeast

New York AG orders Manhattan hospital to resume gender-transition treatment for transgender youth

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

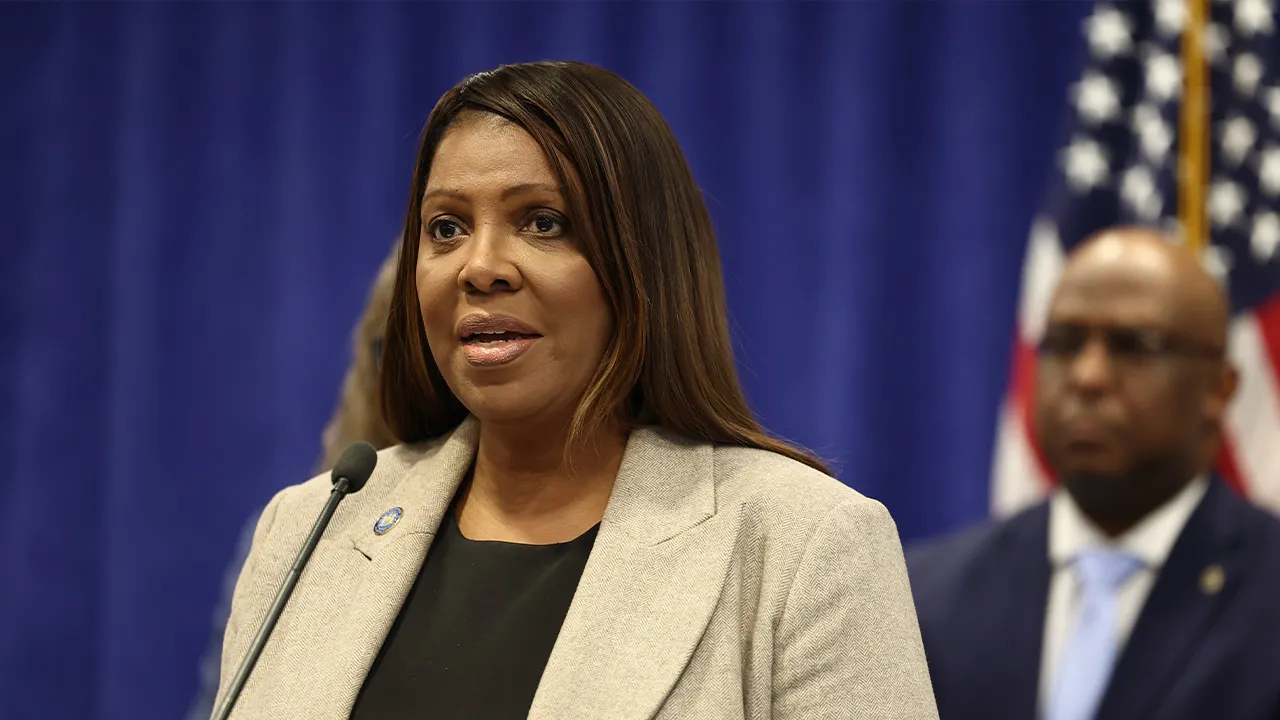

New York Attorney General Letitia James is instructing a Manhattan hospital to resume offering gender-transition treatment to transgender youth after it ended such treatments last month over funding threats from the Trump administration.

NYU Langone’s decision to close its Transgender Youth Health Program violated the state’s anti-discrimination laws by “jeopardizing access to medically necessary healthcare for some of the most vulnerable New Yorkers,” James wrote in a Feb. 25 letter first made public this week.

James’ office threatened “further action” if the hospital does not immediately resume offering hormone therapies, puberty blockers and other treatment to transgender youth.

New York Attorney General Letitia James is instructing a Manhattan hospital to resume offering gender-transition treatment to transgender young people. (Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images)

NYU Langone, one of the city’s largest hospital systems, said last month it would stop providing certain gender-transition treatments for patients under the age of 19.

“Given the recent departure of our medical director, coupled with the current regulatory environment, we made the difficult decision to discontinue our Transgender Youth Health Program,” NYU Langone spokesman Steve Ritea said in a statement at the time. “We are committed to helping patients in our care manage this change. This does not impact our pediatric mental health care programs, which will continue.”

The hospital ceased admitting new patients into its transgender youth program last year after President Donald Trump signed an executive order entitled “Protecting Children from Chemical and Surgical Mutilation,” which aims to restrict gender-transition treatment for people under 19.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has announced a proposal to cut federal Medicaid and Medicare funding to hospitals that provide these treatments to transgender young people. (Andrew Harnik/Getty Images)

Referencing Trump’s order, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services later announced a proposal to cut federal Medicaid and Medicare funding to hospitals that provide these treatments to transgender youth.

But the Feb. 25 letter signed by the attorney general’s health care bureau chief, Darsana Srinivasan, said the proposal did not officially change federal law and did not affect a “medical institution’s existing duties and obligations under New York law.”

“The sudden discontinuation of medically necessary transgender healthcare can have severe, negative health outcomes,” Srinivasan wrote. “Accordingly, the Attorney General is extremely concerned by your institution’s decision to cease the provision of care to this vulnerable, minority population.”

LETITIA JAMES SUES HHS OVER TYING FEDERAL FUNDS TO TRANSGENDER POLICY

NYU Langone said last month it would stop providing certain gender-transition treatments for patients under the age of 19. (Stephanie Keith/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE FOX NEWS APP

The letter gives the hospital until March 11 to show its compliance, although it is unclear what steps would be taken if it fails to resume the treatments.

Several other hospitals across the country have also halted transgender youth treatments following Trump’s executive order and funding threats.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Read the full article from Here

Boston, MA

Charlotte plays Boston on 5-game win streak

Charlotte Hornets (31-31, ninth in the Eastern Conference) vs. Boston Celtics (41-20, second in the Eastern Conference)

Boston; Wednesday, 7:30 p.m. EST

BETMGM SPORTSBOOK LINE: Celtics -6.5; over/under is 214.5

BOTTOM LINE: Charlotte is looking to keep its five-game win streak alive when the Hornets take on Boston.

The Celtics are 27-13 against Eastern Conference opponents. Boston is sixth in the NBA with 46.2 rebounds led by Nikola Vucevic averaging 8.8.

The Hornets are 19-21 in conference matchups. Charlotte is 7-8 when it turns the ball over less than its opponents and averages 15.0 turnovers per game.

The Celtics average 15.5 made 3-pointers per game this season, 2.7 more made shots on average than the 12.8 per game the Hornets allow. The Hornets average 16.0 made 3-pointers per game this season, 2.1 more made shots on average than the 13.9 per game the Celtics allow.

TOP PERFORMERS: Jaylen Brown is averaging 29 points, 7.1 rebounds and five assists for the Celtics. Payton Pritchard is averaging 17 points and 5.8 assists over the past 10 games.

Kon Knueppel is averaging 19.2 points, 5.5 rebounds and 3.5 assists for the Hornets. Brandon Miller is averaging 22.7 points, 5.3 rebounds and 3.6 assists over the past 10 games.

LAST 10 GAMES: Celtics: 8-2, averaging 109.4 points, 50.7 rebounds, 27.1 assists, 6.1 steals and 6.4 blocks per game while shooting 45.7% from the field. Their opponents have averaged 98.5 points per game.

Hornets: 7-3, averaging 117.3 points, 47.8 rebounds, 27.4 assists, 8.5 steals and 4.2 blocks per game while shooting 45.6% from the field. Their opponents have averaged 106.2 points.

INJURIES: Celtics: Jayson Tatum: out (achilles), Neemias Queta: day to day (rest).

Hornets: Coby White: day to day (injury management).

___

The Associated Press created this story using technology provided by Data Skrive and data from Sportradar.

Pittsburg, PA

2 young girls found dead in suitcases in Cleveland, police say

The bodies of two young girls were found inside suitcases in Cleveland, Ohio, police said on Tuesday.

In a press conference, Cleveland Police Chief Dorothy Todd said on Tuesday that the bodies of the two girls were found in suitcases buried in shallow graves on Monday evening. One of the girls was believed to be between the ages of 8 and 13 years old, while the other was believed to be 10 to 14 years old. Neither girl was identified as of Tuesday night.

“This is a priority,” Todd said during Tuesday’s press conference. “This is a traumatic event for our officers, for the community, and this is just such a tragic incident, but we are trying to develop any leads we can.”

Police said there are no active missing persons reports in Cleveland that match the two victims.

Officials said someone walking their dog near East 162nd Street and Midland Avenue found what appeared to be a body inside a suitcase around 6 p.m. on Monday. When officers responded to the scene near Ginn Academy, they found one of the bodies stuffed in a suitcase in a shallow grave. The second shallow grave with the body stuffed in a suitcase was found after officers searched the area.

“This is a field close to the school over there,” Todd said. “This is just a residential neighborhood that I’m sure a lot of people do frequent.”

The Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office has custody of the bodies and will identify the girls. Todd said there is no clear indication of possible causes of death for the girls or how long the girls were there.

“It was some time, so it’s not something that was recent,” Todd said.

There is no suspect, Todd added. Anyone with information can contact the Cleveland police at 216-623-5464.

“Usually in residential areas, you know what’s happening in your neighborhood, something just seems a little bit off,” Todd said. “That’s why we’re asking that anyone who has anything that they believe to be information directly related to or suspicious, that they give us a call.”

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts7 days ago

Massachusetts7 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO7 days ago

Denver, CO7 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Florida3 days ago

Florida3 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Oregon5 days ago

Oregon5 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Maryland3 days ago

Maryland3 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Wisconsin3 days ago

Wisconsin3 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin