Louisiana

Raffles, extra recess, ‘Together Tuesdays’: How Louisiana schools are coaxing kids to show up

Sabrina Carter wants students to look forward each morning to getting on her school bus – and look forward to getting to class.

So she learns the name of every child on her New Orleans bus route, greeting them one by one as they climb on board. She also gives them points for good behavior that they can cash in for treats.

As Carter sees it, every person who works with students can do something to improve attendance.

“It starts with everyone who encounters these kids,” she said.

Carter’s strategies – offering incentives and building relationships – are the same ones schools across Louisiana are betting on to help improve student attendance, which tanked during the pandemic and has not yet fully recovered.

For educators, it’s a major concern.

Students who miss a lot of school are at risk of a number of negative outcomes, including lower test scores, poor grades, and diminished social and emotional health. Chronic absenteeism can also prevent children from reaching crucial milestones, such as being able to read proficiently by third grade.

School bus driver Sabrina Carter hugs elementary students as they get off the bus to go to school in New Orleans, La., Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. (Photo by Sophia Germer, The Times-Picayune)

Chronically absent students also are more likely to drop out of school, worsening their job prospects and future health and increasing their risk of getting caught up in the criminal justice system.

“You name the thing we’re trying to avoid, and missing school increases the likelihood of it,” said Todd Rogers, a behavioral scientist and professor of public policy at Harvard University who has studied the role attendance plays in student success.

Chronic absenteeism, or the share of students who miss at least 10% or more of a school year, surged nationwide after the pandemic. But as some parts of the country began to see a decline, Louisiana’s rate grew to 23% by 2022-23, an increase over the previous school year and nearly double the pre-pandemic rate. (Rates for the 2023-24 school year have not been released.)

There are many reasons why kids miss school, ranging from illness to a lack of reliable transportation to housing instability to bullying and more. Districts are trying to combat the problem by identifying kids at risk for becoming chronically absent and intervening early.

“There is no silver bullet when it comes to solving absenteeism,” Rogers said, adding that it should be approached like a chronic illness: “You don’t cure it, you continue to treat it.”

Motivate kids

One of the best ways to improve attendance, experts say, is also the simplest: Make students want to show up.

During the first week of school this year, each student at Southside Junior High School in Denham Springs plucked the name of one of six “houses” out of a Harry Potter-themed bucket while their classmates looked on with anticipation. The students in each house will work together for the duration of their middle school careers, competing as a team to earn points and rewards.

District officials say the house system encourages students to forge strong bonds, fostering a sense of camaraderie and shared purpose.

It’s a tactic the school, which saw more than half of its students qualify as truant during the 2022-23 academic year, is trying to improve its culture and create an environment where kids are excited to show up.

“We want our students to want to come to school,” said Principal Wes Partin. “We’re always trying to find ways to positively motivate our students.”

Other districts are offering students prizes and other incentives for good attendance.

Desoto Parish teachers give out small perks to kids with good attendance, like extra recess or “free dress days” where they don’t have to come to school in uniform.

In Lafourche Parish, where chronic absenteeism jumped by eight percentage points between 2019 and 2023, students who come to school multiple days in a row can enter a raffle to win prizes such as Xbox game time.

Under state law, district officials must report students who rack up more than five unexcused absences to their parish’s family or juvenile court. But some districts have created programs to work with families before notifying the state.

For Lafourche’s program, school officials meet with families to discuss the reasons behind a child’s absences. Together they develop a plan to improve the student’s attendance, which the district’s attendance team closely monitors.

“We’re almost always able to remedy the issue,” superintendent Jarod Martin said.

Analyze the data

Experts say that catching absenteeism early is crucial — and that the best way to do that is by closely tracking attendance data.

Desoto’s Parish’s school district keeps a dashboard themed like a baseball scoreboard on social media to track every school’s attendance rate. Officials say the dashboard provides transparency and creates healthy competition among schools to improve their rates.

Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a national nonprofit that aims to improve student attendance, encourages districts to review attendance data frequently to identify kids who are on their way to becoming chronically absent. Then school staffers can find the reasons why each child is missing class and address the root causes before it snowballs, she said.

Jennie Ponder, director of the Truancy Assessment and Service Center in Baton Rouge, which helps schools identify and support truant students, explained that most districts employ at least one attendance clerk to oversee attendance data. Once a teacher submits their attendance sheet, the clerk notes which children have been marked absent and periodically sends that information to the state.

“It’s a very big responsibility when you are in charge of that data,” Ponder said.

In Rapides Parish, a truancy task force of around seven people keeps tabs on attendance data to spot students with frequent absences. This summer, district officials visited the homes of students who were identified as chronically absent last school year to talk to families, see why their children have been missing class and connect them with any needed resources.

“We’re not just going to sit back and wait for them to be chronically absent again,” said Mary Helen Downey, the district’s community engagement coordinator.

Build strong school communities

Perhaps the best way to get students to school is to create an environment where they feel safe and welcomed.

The GRAD Partnership, a collective of districts and community organizations across the country, developed a program in 2022 in which 49 middle and high schools tried to foster relationships between teachers, students and families to reduce absenteeism. The group suggests giving students opportunities to work together in class and having staff members host student clubs as ways to cultivate connections. In a 2024 report, the collective said that chronic absenteeism rates dropped by nearly 12% and course failure rates dropped by 5% in the participating schools.

“It’s hard to imagine anything more important than kids feeling loved and known at school,” said Rogers, the Harvard researcher. “The more adults who have caring relationships with kids, the better.”

In Louisiana, Iberville Parish Schools recently introduced its “Presence Matters” initiative, where kids with a high number of absences are assigned a district staff member as a mentor. The mentors, who can include bus drivers, food service workers and gym teachers, check in with their mentees and families frequently.

“If there are challenges or barriers that are hindering” kids from coming to school, “we want to be a support for the family,” said Rebecca Werner-Johnson, the district’s executive director of academics.

This year, the program expanded to include local churches and community members.

Brian Beabout, an associate professor in educational leadership at the University of New Orleans and a former high school teacher, said some schools require their students to join a club or a sport to foster meaningful relationships.

Even if a club doesn’t meet every day, it can be another place where “people notice if you’re not there,” Beabout said. “It creates this social belongingness.”

Once a month, Rapides Parish School District holds its “Together Tuesdays” program, where school staff, community leaders and students gather for lunch and conversation. Sometimes the district has special guests welcome the students when they arrive for the meals.

“If it’s football season, some of the football players will greet the kids and get them out of the car,” said Terrence Williams, the district’s director of child welfare and attendance. “It’s a way for children to interact with people who they otherwise would not come in contact with.”

Williams recalled an instance when a community member discovered a pair of siblings, ages 12 and 8, whose parents had not enrolled them in school. The community member had participated in Together Tuesdays, so they contacted the program organizers.

School officials notified the court system, but they also approached the family to see if they could get some answers, Williams said. They discovered the family was struggling to afford school uniforms, which the district provided.

Now, Williams said, the siblings are in school and thriving academically.

“Those relationships we’re building with the community helped facilitate the whole thing,” he said. “They’ve not missed one day of school since we found them.”

Louisiana

Officials confirm Pensacola Beach residue is algae, not oil from Louisiana spill

PENSACOLA BEACH, Fla. — A local fisherman raised concerns about the substance now coating Opal Beach, citing a recent oil spill off the coast of Louisiana.

WEAR News went to officials with the Gulf Islands National Seashore and Escambia County to find out the cause.

They say it’s not related to an oil spill, but is in fact algae.

The Marine Resources Division says they can understand beachgoers’ concerns, and hope to raise awareness.

“You don’t even want to get near it because it’s so gooey and sticky,” local fisherman Larry Grossman said. “It was accumulating on my beach cart wheels yesterday, and it felt like an oil product.”

Grossman messaged WEAR News on Monday after noticing something brown and oozy in the sand. He says it started showing up by Fort Pickens and stretched down to Opal Beach.

Grossman said a park service employee told him it could be oil from a recent spill in Louisiana. So he took a message to social media, sparking some reactions and raising questions.

“it certainly didn’t seem like an algae bloom because I was in the water, I caught a fish and I put some water in the cooler to keep my fish cool and it almost looked like oil in it,” Grossman said. “I know some people think it’s an algae bloom, but it certainly smelled and felt and looked like oil.”

A Gulf Islands National Seashore spokesperson confirmed to WEAR News on Tuesday that the substance is algae.

WEAR News crews were at the beach as officials with the Escambia County Marines Resources Division came out take samples.

“What I found here washed up on the beach is some algae — filamentous algae, single celled algae — that washed ashore in some onshore winds,” said Robert Turpin, Escambia County Marines Resources Division manager. “This is the spring season, so with additional sunlight, our plants, they grow in warmer waters, with plenty of sunlight.”

Turpin says this algae is not harmful.

He also addressed the concerns that this could be oil, saying he’s familiar with what oil spills look like.

He says he appreciates when people like Grossman raise the concerns.

“The last thing in the world we want is something to gain traction on social media that is faults in nature that could harm our tourism,” Turpin said. “Our tourism is very important to our economy, and we want to give the right information out to the public so we all enjoy the beaches and enjoy them safely.”

Turpin says if you see something or suspect something may be harmful on the beach, avoid it and contact Escambia County Marine Resources.

Louisiana

Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry calls for amendment for teacher pay raises

VIDEO: Louisiana 2026 Legislative Session Previewed in Lafayette

At One Acadiana’s Lafayette outlook event, business and policy leaders discussed the 2026 session and what it could mean for jobs, schools and voters.

BATON ROUGE — Gov. Jeff Landry advocated for a constitutional amendment that would create a permanent teacher pay raise as well as an eventual elimination of the state income tax in an opening address to the Louisiana Legislature on Monday.

Landry pushed for the passage of Proposed Amendment 3 on the May 2026 ballot to free up money for teacher pay raises.

He said the amendment would pay down longstanding debt within the Teachers’ Retirement System of Louisiana and enable the state to afford a permanent increase in teacher income. The proposed increases are $2,250 for teachers and $1,125 for support staff.

“With a ‘yes’ vote, we can strengthen the retirement system, improve their take-home pay, and guess what? We can do it without raising taxes,” Landry said.

A bill proposing the elimination of the state income tax, which takes in about $4 billion annually, was pre-filed earlier in the year by Rep. Danny McCormick, R-Oil City. Where the money will come from to supplement the loss is currently unclear.

McCormick said in an interview with the LSU Manship School News Service that to encourage more young adults to stay in Louisiana, “we need to do away with the state income tax.”

“This is a conversation piece that hopefully we can figure out where to make cuts in the government so we can get the people their money back,” McCormick said.

But Senate President Cameron Henry, R-Metairie, said at a luncheon at the Baton Rouge Press Club that if the Legislature “can be disciplined” this session, residents could anticipate a 0.5% decrease in state income tax during next year’s session. He also said bigger tax cuts have to be planned over a longer budget cycle.

Within education changes, Landry commended the placing of the Ten Commandments in classrooms, approved by the Louisiana Supreme Court in a decision handed down last week.

“You have staked the flag of morality by recognizing that the Ten Commandments are not a bad way to live your life,” Landry said. “Students who don’t read them will likely read the criminal code.”

Landry’s budget proposed an $82 million increase for corrections services following 2024 tough-on-crime legislation that eliminated parole and probation, increased sentencing and encouraged harsher punishments.

Landry directed his criticism toward the New Orleans criminal justice system, which he feels is lacking accountability, especially in courtrooms.

“Judges hold enormous power, but they are not social workers with a gavel,” he said. “They are the final gatekeepers of public safety.”

The Orleans Parish criminal justice system relies on state and local funding stemming from revenues from fees imposed on those arrested, according to the Vera Institute. Landry said the state spends twice as much on the Orleans system as it does in East Baton Rouge Parish, the largest parish in the state.

“Being special does not mean being exempt from accountability,” Landry said.

Overall, Landry pushed for fewer and different ideas compared to the sweeping agenda he laid out at the start of previous legislative sessions. Henry mentioned at the Baton Rouge Press Club that the governor would like for this session to be a “member-driven session instead of an administrative session.”

Landry spoke only in general terms about his proposal for more funding for LA Gator, his program to let parents use state money to send their children to private schools.

“We must find a path so that the hard-earned money of parents follow their child to the education of their choice,” he said.

He has proposed doubling funding for the LA Gator program from $44 million a year to $88.2 million. The likelihood of this occurring is yet to be seen, as prominent lawmakers such as Sen. Henry are hesitant to approve an increase in funding.

Landry similarly did not mention carbon capture projects, despite the issue gaining traction from affected parish residents and lawmakers.

House Speaker Phillip DeVillier, R-Eunice, told the Baton Rouge Press Club last week that 22 bills have been filed in the House that he would consider “anti-carbon capture.”

Landry also cited data centers and other giant industrial development projects and touted his administration’s success in bringing more jobs to Louisiana and in helping to lower insurance premiums over the past year.

“May we continue to employ courage over comfort, and if we do, there is really no limit to what we can do for Louisiana,” Landry said.

Louisiana

Louisiana’s LNG exports are driving out fishermen and driving up utility bills across the U.S.

Phillip Dyson once tried working a job that wasn’t shrimping. He lasted three days on an oil rig before going right back to his boat.

“The man said, you just tell me you want the job, we’ll fire the other guy,” he said with a laugh. “I said, don’t fire that man, ’cause I ain’t coming back.”

For more than half a century, Dyson has been fishing the coastal waters of Cameron, Louisiana. Forty years ago, Cameron Parish was the top seafood port in the United States. Today, it’s ground zero for America’s LNG export boom, a multibillion-dollar industry — the U.S. is the top exporter in the world — that has reshaped the landscape, the economy, and the daily lives of the people who have lived here for generations.

When Dyson looks out from the shrimp dock now, he doesn’t recognize what he sees: spindly cranes, cylindrical cooling towers and the constant hum of the construction and processing of liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals rising above the marsh.

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

The terminals run day and night, super-cooling natural gas into liquid form where it’s loaded onto massive tanker ships for export to places like Europe and Asia.

Shrimpers like Dyson are catching about half of what they used to, driving many out of the industry.

“There used to be 200 shrimp boats in this town — down to 15,” Dyson said. “You went from a fishing town to a town that didn’t care less about the fishermen.”

Dyson is stubborn and set in his ways. Shrimping is all he knows. He doesn’t want to leave Cameron. He buried his parents here. Scattered his daughter’s ashes in the water.

“I would never want to leave her behind,” he said. “But I’m gonna have to.”

‘You’re just surrounded’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

Cameron Parish was an attractive destination for reasons both geographic and financial. It sits close to the Haynesville Shale formation, one of the country’s most productive natural gas fields, has no parish-wide sales tax and LNG companies have secured industrial tax exemptions that, according to community advocates, amount to nearly a billion dollars a year across the three operating terminals — roughly $6 million per permanent job created.

“They don’t only export gas — they export the profits,” said James Hiatt, a former oil and gas worker who founded For a Better Bayou, a southwest Louisiana environmental community organization. “That’s the key.”

The company at the center of the expansion is Venture Global, which operates the Calcasieu Pass terminal, known as CP1, just outside of Cameron. In a March earnings call, the company reported it made more than $6 billion in 2025 alone — tripling its profits from the previous year.

In an interview last year on CNBC, Venture Global’s CEO, Mike Sabel, described the company in terms residents find difficult to square with their daily reality: “Ultimately our business is that we manufacture and operate machines that produce money.”

President Donald Trump’s administration approved a second Venture Global terminal in Cameron — CP2 — just two months after taking office in 2025. Nationally, 17 new export terminals are either under construction or have won approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Six of them are in southwest Louisiana.

Robyn Thigpen, a local resident and executive director of the advocacy group Fishermen Involved in Saving Our Heritage (FISH), described the sense of encirclement many people feel.

“When you turn here,” she said, pointing in different directions from the beach in Cameron, “the cranes off in the distance is the expansion to CP1. 12 miles back into town is Hackberry LNG. Probably about 30 miles this direction is Sabine LNG. So you’re just surrounded.”

‘No shrimper can make it here’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

Last August, while Venture Global was dredging a shipping channel at CP1 — pumping out mud and sediment to clear a path for vessels — something went wrong. The company spilled hundreds of acres of sediment into the surrounding marsh.

The mud blanketed the area where Tad Theriot, a shrimper turned oysterman, had been growing his harvest. He pivoted to oyster farming two years ago, after years of declining shrimp catches made the traditional livelihood impossible to sustain.

The dredge spill devastated his oyster operation almost overnight.

“Half of them died,” Theriot said. “We lost 50% on the big ones, even more than that.”

Out on the water, the evidence was plain — oysters pulled from cages bore what his farming partner Sky Leger called “mud blisters,” deposits of silt visible inside the shell.

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

“Before you try, tell me — would you eat it if you knew that that was there?” Leger said, pointing to dark splotches on the iridescent cup of a fresh oyster. “How does that get there?”

Venture Global told More Perfect Union and Gulf States Newsroom in a statement that the “isolated discharge was quickly contained,” and that there were “no significant offsite impacts” as a result of the spill.

The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries documented increased oyster mortality near the spill site in September, and fishermen have since requested a more comprehensive government study.

To date, no significant enforcement action has been taken against the company.

But according to documents obtained by More Perfect Union, Venture Global offered some affected fishermen $20,000 — on the condition they could never sue or speak negatively about the company again. When asked about the offer, Venture Global said the company “has communicated directly” with local fishermen “to develop mitigation and remediation plans, and minimize the potential for an event like this again.”

Theriot said he’d never take the money.

“That’s not right,” he said flatly. “I have hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of oysters. I want hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Advocates like Hiatt called the settlement offers part of a pattern the company is using to sidestep accountability through financial and political power.

“After this spill, more people are understanding that these corporations don’t give a f— about you,” he said. “All they care about is how much money they can make.”

Last month, a pipeline part of an under-construction project operated by Delfin LNG ruptured near Holly Beach in Cameron Parish. The ensuing explosion resulted in “catastrophic injuries” to a contractor working for the company, according to a lawsuit filed in Texas that accused the company of negligence and failing to “ensure the pipeline was free of flammable vapors and materials.”

“It’s a reminder that these things are happening in a community that doesn’t even have a hospital,” Thigpen said, noting that the worker was taken to a hospital in Port Arthur, Texas, roughly 45 minutes away. “It’s another example of why we can’t trust these companies to do the right thing.”

‘You can’t afford this and food’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

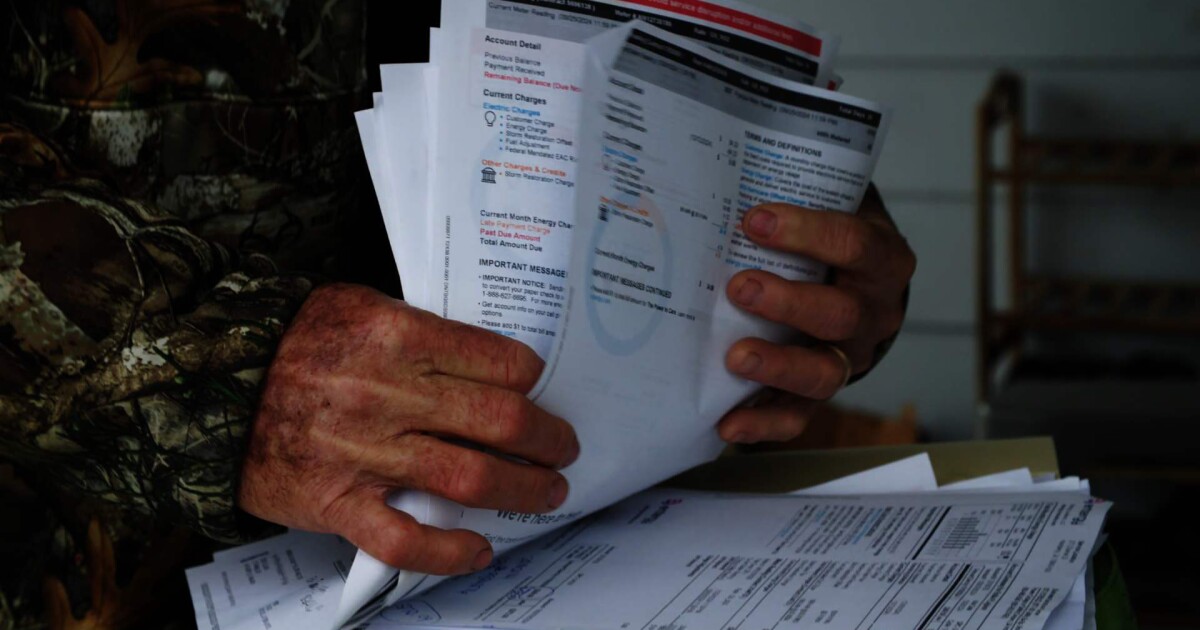

The impacts of Cameron’s transformation don’t stop at the bayou’s edge. The LNG export boom is being felt in the utility bills of Americans across the country.

Eight LNG export terminals now consume more natural gas each day than all 74 million American households connected to gas utility service combined. The federal government projects the benchmark price of natural gas will average 22% higher in 2026 than in 2025, citing LNG exports as a driving factor.

A Public Citizen analysis found domestic natural gas prices were $12 billion higher for residential customers in just the first nine months of 2025 compared to the same period the year before — roughly $124 per household.

“It’s simple supply and demand,” Slocum said. “You’re forcing Americans to compete with their counterparts in Berlin and Beijing for access to U.S. natural gas. And that pushes the domestic price up. The more we export, the higher the prices the rest of Americans will pay to heat and cool their homes.”

In Hackberry, Louisiana — minutes down the road from Cameron Parish’s other export terminal — fisherman Eddie Lejuine and his wife Michelle have watched their bills climb. Lejuine depends on a refrigerated storage container to keep his catch marketable. Without it, he can’t work.

“You can’t afford this and food,” Michelle Lejuine said. “What are you gonna do? You gonna eat or are you gonna have electricity?”

Eddie Lejuine put it plainly: “We’re catching less fish, [making] less money, paying higher bills.”

Trump’s promise, the industry’s windfall

During the 2024 campaign, Trump pledged to cut Americans’ energy bills in half within 12 months. He repeated it at rallies and put it in writing in a Newsweek op-ed.

On his first day back in the White House, one of his earliest executive orders undid former President Joe Biden’s pause on pending LNG export approvals — a pause that was implemented, in part, because consumer advocates argued the existing review process failed to account for domestic price impacts.

The ties between Venture Global and the Trump administration run deep. According to reporting by the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, the company’s CEO was present at a private 2024 meeting at which Trump reportedly asked oil and gas executives to contribute $1 billion to his campaign.

Slocum argued the gap between Trump’s promise and his policy is not an accident.

“What Trump has done is to prioritize the financial interests of the natural gas industry,” he said. “And the natural gas industry’s primary financial directive is to maximize LNG exports.”

Electricity prices jumped 6.9% in 2025 year over year, according to Goldman Sachs.

‘Find somewhere else to build this’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

More than 90% of Cameron Parish voted for Trump in 2024. The mood among the fishermen who remain is harder to categorize than partisan politics.

When asked if he’d vote for Trump again, Lejuine said: “No, I’m not. I’m hoping we have a better selection of something.”

Hiatt, a self-described third-generation oil and gas worker, framed it as a matter of basic fairness rather than ideology.

“This is ‘America Last’ policy,” he said, “to export our natural resources to the highest bidder at the expense of every American.”

Dyson, standing at the dock in the late afternoon light, said what he would tell Venture Global and the politicians like Trump and Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry, who championed the expansion: “Find somewhere else to build this s—. I never thought I’d have seen this place like this. Never in my lifetime.”

His electricity bill runs $350 to $500 a month for a 990-square-foot house, he said. He and his wife receive about $1,300 a month together on Social Security. With what he’s catching, it’s not enough.

He said he won’t stop shrimping, but he can’t do it in Cameron.

“This is what I do. That’s what I’m gonna do till they throw dirt on me. That might not be here, but I will fish till it’s over.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. This story was produced in collaboration with More Perfect Union.

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Pennsylvania5 days ago

Pennsylvania5 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Detroit, MI4 days ago

Detroit, MI4 days agoU.S. Postal Service could run out of money within a year

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death

-

Miami, FL6 days ago

Miami, FL6 days agoCity of Miami celebrates reopening of Flagler Street as part of beautification project