This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with The Seattle Times. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Seattle, WA

The Cleanup of Seattle’s Only River Could Cost Boeing and Taxpayers $1 Billion. Talks Over Who Will Pay Most Are Secret.

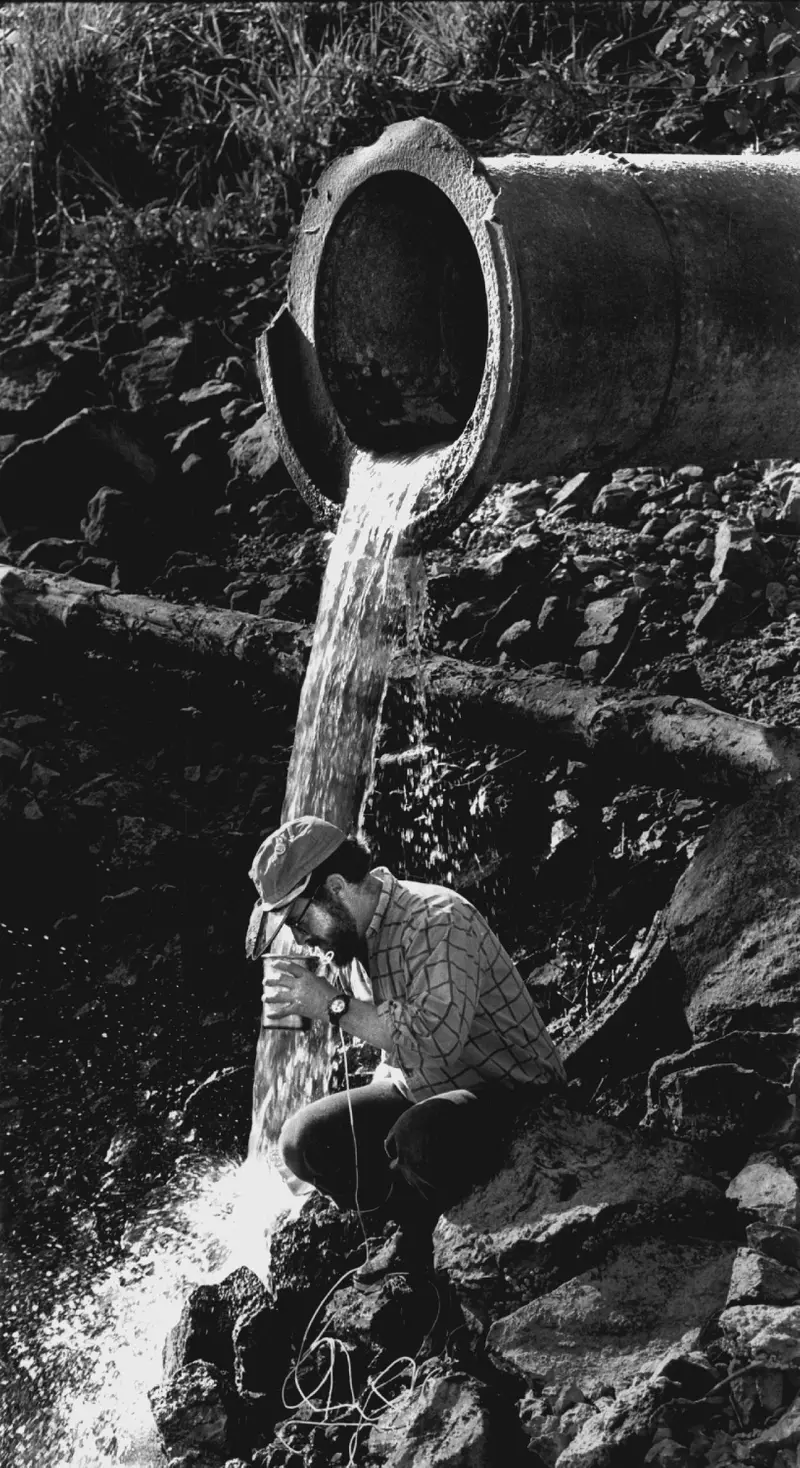

In its early days as a major aircraft manufacturer, Boeing was remarkably open about toxic chemicals flowing from its factory into the neighboring Duwamish, Seattle’s only river and a longtime source of food, tradition and culture for Indigenous people.

In fact, the company described the Duwamish River as “a natural collector for Boeing’s fluid wastes” in a 1950 magazine article Boeing produced for its employees. Boeing said at the time that it had a handle on the situation — asserting, for example, that some of its most volatile waste would be neutralized by chemicals released by other polluters.

Today the waterway is among the nation’s most contaminated, a full-scale cleanup is scheduled to begin next year, and Boeing is deep in negotiations over how to split the cost with other leading landowners on the river: the city, adjoining King County and the Port of Seattle.

As with most negotiations conducted under the nation’s Superfund cleanup law, the parties agreed long ago to keep details of their talks secret. But a short-lived lawsuit, filed by the port last year and withdrawn in June, offered a glimpse of a staggering dollar figure that’s never been part of the public discussion.

In court papers accusing Boeing of trying to slough off its share of the cleanup bill, the port said the total cost could top $1 billion. The sum is more than double any estimate previously made public, and it would make the Duwamish one of the nation’s costliest cleanups on record. Government websites still put the cost at about $340 million.

The dollar amounts alluded to in the 2022 lawsuit point to a high-stakes and largely hidden deliberation between the region’s biggest government players and a major company born in Seattle more than a century ago.

Credit:

Alan Berner/The Seattle Times

Whatever the parties agree to, taxpayers may never know whether the cost split was fair because how the decision was reached is intended to remain secret.

This month, in response to questions from The Seattle Times and ProPublica, Boeing said it was the port that is refusing to do its part.

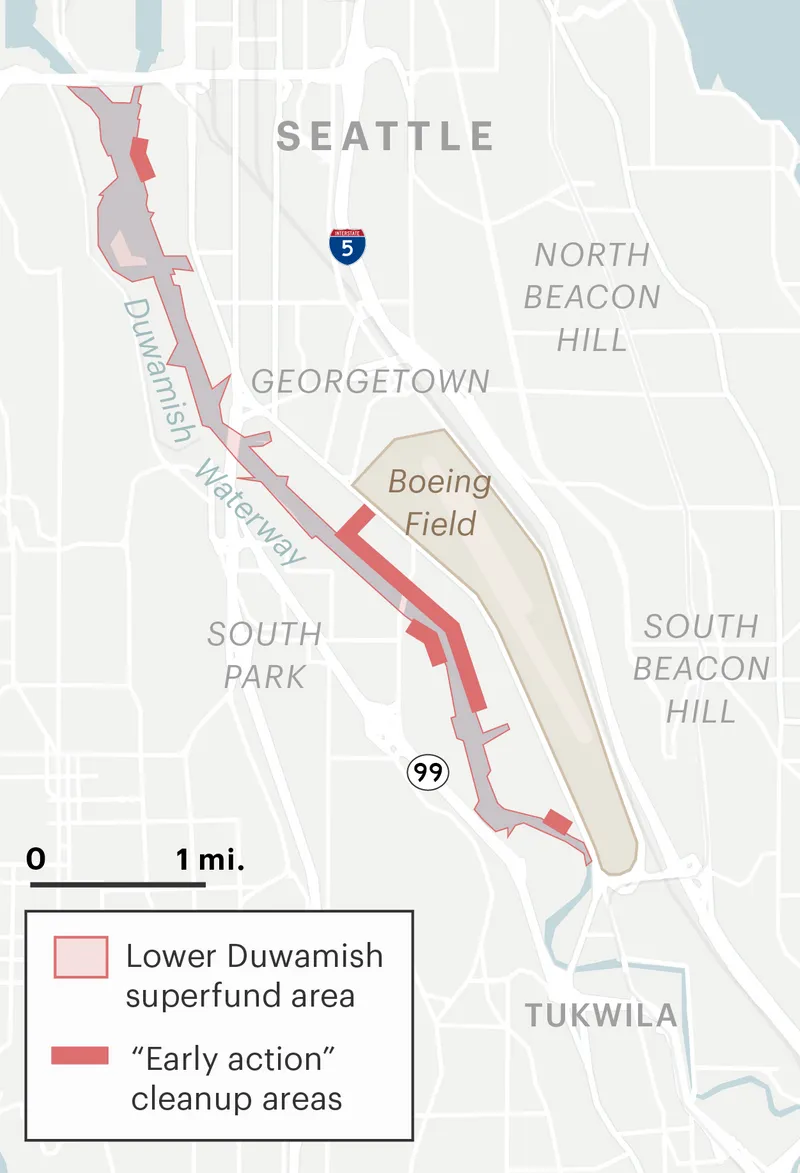

Local Government Agencies and Boeing Have Spent More Than $200 Million Cleaning Up “Early Action” Sites in the Duwamish Superfund Area Since 2001 A full-scale cleanup is scheduled to begin next year. The Port of Seattle says it could cost $1 billion, which would make it one of the nation’s costliest Superfund cleanups.

Credit:

Lucas Waldron/ProPublica

“We were extremely disappointed in the Port’s refusal to pay its equitable share of the cleanup and in their decision to subsequently file and then dismiss a lawsuit,” the company said in a written statement.

Boeing declined to comment on the private negotiations or disclose the exact amount it agreed to pay, but it said that the company expects to spend “hundreds of millions of additional dollars.”

This summer, Boeing joined with the city and county in issuing a separate statement saying the lawsuit’s allegations do not affect their “ongoing and lasting commitment to restoring the water quality of the Lower Duwamish for people, salmon, and orcas.”

“The City of Seattle, King County, and Boeing will continue to work to advance the cleanup to benefit this generation and those that will follow,” the joint statement reads.

The port continues to claim, as it did in its lawsuit against Boeing, that negotiations could saddle taxpayers with “tens of millions of dollars” in costs for which the company is liable.

Meanwhile, people who have waited for the Duwamish to be restored say they worry about the lack of information available to the public.

“The reality is there isn’t a lot of transparency,” said Paulina López, executive director of the Duwamish River Community Coalition, a federally recognized task force dedicated to representing community interests in the cleanup.

What advocates say worries them even more is the possibility that an impasse over who pays, two decades into the river’s Superfund listing, will mean yet further delays in restoring the river.

Credit:

Seattle Times Archives

Two centuries ago, as white settlers began to develop the land, Native tribes successfully negotiated for their fishing rights on the Duwamish River to preserve a cultural touchpoint and vital food source. The city of Seattle eventually recognized the river’s value as a pathway for transporting cargo. It scraped away the winding river’s marshy banks, straightened its natural bends and dredged its floor.

What was once a complex ecosystem of mudflats, native plants and spawning fish became a sprawling industrial corridor.

Credit:

Seattle Times Archives

Boeing found a home along the Duwamish in 1916, launching an operation from an abandoned shipyard where it built seaplanes. In the 1930s, the company developed the nation’s first four-engine bomber, and the federal government eventually ordered about 7,000 B-17s over the course of World War II. By the end of the war, Boeing’s plant along the Duwamish expanded to nearly 1.7 million square feet.

It ultimately became one of the largest landowners in the industrial district, but publicly owned facilities also contributed toxins: water runoff tainted with chemicals from the city’s steam plant, pollution from the port’s cargo terminals and unfettered sewage dumped from King County’s wastewater system.

The river is now contaminated with heavy metals and cancer-causing chemicals, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Credit:

Kevin Clark/The Seattle Times

Along the river now are large health advisory signs warning the public not to eat bottom-feeding fish and to limit consumption of certain salmon, a warning system King County calls “Fun to Fish, Toxic to Eat.” Even direct contact with river mud is a risk, the state health department warns. Tribal fishing, protected by an 1855 federal treaty, continues along the river despite declining fish populations and public health warnings.

Some of these contaminants can be traced to Boeing’s plants along the river, which is why the federal government has named it as one of the major responsible parties.

Boeing’s 1950 magazine article, brought to light in the port’s lawsuit, described its efforts to curb pollution, but the company openly acknowledged that “any unrestrained liquid emptied on the Boeing premises is bound sooner or later to get into the Duwamish.”

Credit:

Alan Berner/The Seattle Times

Tracy Collier, a toxicologist who worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center for three decades and who read the magazine article at The Times’ request, said that it makes legitimate scientific arguments about how pollutants can be diluted and neutralized, but that it’s impossible to tell from the description alone whether Boeing successfully reduced the amount of contamination.

It’s also important to note, Collier said, that some contaminants now found in high concentrations in the river weren’t on the radar 70 years ago. Boeing is one of the parties known to have contributed PCBs, for example, according to the state Department of Ecology.

Credit:

Greg Gilbert/The Seattle Times

“We didn’t know in 1950 that PCBs were going to be persistent and as toxic as they are,” Collier said. The chemical wasn’t banned by the EPA until the 1970s.

Boeing said in a statement that its article described disposal practices that were the industry standard at the time. The company added that it proactively took the steps described in the article before federal and state environmental laws took effect.

In early 2000, a survey by the EPA revealed that the river was eligible for Superfund designation, meaning it was one of the most polluted sites in the country.

The Superfund, created by Congress in 1980, was meant to address the nation’s legacy of toxic industrial waste by establishing a process to pay for cleanups. It was also known to result in costly legal battles. The port, city, county and Boeing hoped to divvy up the tab and clean the river without triggering the Superfund process.

“They were worried about the stigma it would cast on the city, and some believed that they could clean the river up faster and better without EPA dogging their efforts,” BJ Cummings, community engagement manager for University of Washington’s Superfund Research Program, wrote in her book “The River That Made Seattle,” which details the Duwamish’s history.

Credit:

Alan Berner/The Seattle Times

But federal environmental regulators needed to sign off. They wanted an agreement that would allow them to go after polluters for damage up to three years after completion of the cleanup, just as they could under the Superfund.

Boeing would not agree. The company told a Times reporter in 2000 that it caused only a small part of the pollution and was worried that it would be stuck with a big share of the cleanup.

“We couldn’t sign the agreement without assurances that there would be an equitable outcome,” a Boeing spokesperson said at the time.

The Duwamish River landed on the national Superfund list the following year.

Credit:

Tom Reese/The Seattle Times

With EPA oversight, the three government agencies and Boeing agreed to equally front the bill for testing the river water, surveying the contamination and planning the cleanup. They planned to eventually redistribute the costs based on responsibility for pollution, a canon of Superfund law known as the “polluters pay” principle.

What happened next is hidden by an agreement signed by the parties to keep the process private.

This type of process was first created under the Superfund to make it easier for private companies to discuss business practices and liabilities frankly with the EPA. The goal was to have polluters agree among themselves on how to cover cleanup costs.

Credit:

Alan Berner/The Seattle Times

But in this case, the polluters in question include three local governments. Every dollar that Boeing doesn’t pay could end up the responsibility of Seattle-area taxpayers.

Even where the negotiators meet, who is in the room and what evidence is considered are secret. But court documents and interviews offer a few intriguing details about the process so far.

In 2014, the group hired John Barkett, an experienced environmental lawyer from Florida, to act as an outside allocator and deliver a report suggesting how the parties should divide the costs.

Court documents Boeing filed seeking to put the port’s lawsuit on hold describe parties exchanging historical records, responding to detailed questionnaires, providing expert reports, taking depositions and attending meetings to discuss costs.

Barkett provided his final report to the parties last year and hasn’t been involved in the process since, he told The Times and ProPublica, declining to speak in detail about the Duwamish River or the allocation. The news organizations asked the port, the city and the county for a copy of the report, but all declined, citing the nondisclosure agreement among the parties.

Both King County and the city said in separate statements that they believe the ongoing allocation process has been “thorough and fair.” Both said they plan to make their individual shares public once the process wraps up, but neither one plans to release the full report. The reason, the city wrote in an email, is that it “contains each party’s sensitive operational and financial information.”

The allocation report is nonbinding, meaning the parties can adjust or reject Barkett’s suggested breakdown of costs. Court documents show that on July 11, 2022, Boeing agreed to an undisclosed share of the cost. The Port of Seattle filed its lawsuit eight days later.

“Boeing has gleaned billions of dollars in profits over the past several decades partly through externalizing its waste disposal costs by dumping wastes into the Lower Duwamish River,” the port said in its claim.

Credit:

Bettina Hansen/The Seattle Times

The port said it had negotiated diligently for eight years, but that the cost split on the table would force the port to “redirect taxpayers’ funds from projects and programs that benefit the public,” threatening environmental justice initiatives, “employment funds” and projects aimed at expanding public access to the river.

The port’s allegations opened old wounds for tribal leaders who have fought for decades to hold the river’s polluters accountable, said Leonard Forsman, chairman of the Suquamish Tribe, which has fishing rights on the river.

“I know that industries along the river made a lot of money at the expense of our waterway,” Forsman said.

“They were well aware of what they were doing,” Forsman said of corporate polluters, adding that Boeing and other companies “have to acknowledge that and take responsibility.”

Port officials withdrew the lawsuit in June, saying that “litigation is not the most efficient path to resolution at this time.” Any further discussions would once again take place behind closed doors.

Credit:

Karen Ducey/The Seattle Times

The Duwamish River Community Coalition, which represents the public’s interests in the cleanup, feels shut out, said Jamie Hearn, a lawyer for the coalition. “We don’t have access to a lot of information, and responsible parties are very careful to only release certain details,” Hearn said.

Still, as frustrated as Duwamish activists may be about the lack of transparency in the Superfund process, they want to avoid delaying the cleanup any further.

The community is less concerned with who pays the bill than with making sure the cleanup happens on schedule, said López, the executive director of the community coalition.

“We’ve already waited so long,” she said.

Credit:

Alan Berner/The Seattle Times

What is known about the Duwamish cleanup publicly is that it has already cost a lot — and U.S. taxpayers have picked up a big chunk of the bill so far.

The Lower Duwamish Waterway Group, a private-public partnership between Boeing and the three government agencies, says it has already invested more than $200 million in early cleanup projects and habitat restorations along the river, targeting its most polluted parts. These actions have reduced the amount of PCBs in the river’s sediment by half, according to the group.

Boeing said in a statement that it alone invested $115 million on an early cleanup project. In 2015, the company completed a two-year cleanup that turned five acres of industrial waterfront into a wetland habitat with native plants and woody debris. The company touts on its website an award from NOAA for the project.

Boeing recovered $51 million from the federal government in 2018, through a lawsuit that said the Duwamish pollution was the result of the company’s role as a defense contractor during World War II.

Originally, the Superfund was fed by a tax on a variety of polluting industries to ensure cleanups could proceed even if polluting companies went out of business or couldn’t afford to pay.

But since that tax expired, in 1995, taxpayers of all kinds have spent billions of dollars cleaning up hazardous waste released by private companies, according to a 2017 analysis by News21, an investigative journalism project connected to Arizona State University.

The Lower Duwamish River parties are scheduled to embark on the full-scale cleanup as soon as next year.

Credit:

Alan Berner/The Seattle Times

The schedule will be complex and intricate. In-water work, which will involve dredging and barging away contaminated sediment, can only happen during a short window, typically October to February, to avoid interfering with fish migration or fishing treaties. It will likely take years to complete the cleanup.

Removal of contaminants from the river’s most polluted stretch, where Boeing Field airport is located, is supposed to come first, after a final bout of planning and contracting, according to the EPA.

But it isn’t clear how the lengthy cost negotiation will play a role in the timeline. The dozens of parties responsible for the cleanup have to agree to a payment plan and present it to the EPA for approval.

Agreeing is key to avoiding years of litigation and bickering.

The city of Seattle warned as much on its website, where it notes that cleanup parties can disagree, “but everyone knows that those who reject their assigned shares are likely to be sued by the others.”

Seattle, WA

Lobbing Scorchers: Grading the Seattle Sounders’ Offseason

We are back with another offseason episode as the beginning of the 2025 season draws nearer. With the Jesús Ferreira and Paul Arriola trades now official, we grade Seattle’s offseason thus far based on all their moves to date. We also have a handful of headlines from around the league, including more transfer movement, a couple of new coaching hires, and chaos and turmoil engulfing Austin FC.

Donate to LA Fire Relief: https://www.gofundme.com/f/lafc-podcast-raising-money-for-la-wildfire-victims

Seattle, WA

Lauren Barnes returns to Seattle Reign for the 2025 season

Seattle Reign announced on Tuesday that the club has re-signed Lauren Barnes for the 2025 season. The 35-year-old defender and Reign original returns to Seattle for her 13th season with the club.

Barnes currently has the league record for the most appearances (232), starts (224), and minutes (19,795). She was the first player in league history to reach 200 games played. When the 2025 season kicks off, she’ll join Jess Fishlock as the only two players to feature for the same club since the league launched in 2013.

“I’m thrilled to sign a new contract with the Reign, a place that has been my home since I first joined the club in 2013,” said Barnes in a team release. “This club means so much to me – not just for what we’ve accomplished on the field but for the impact we’ve been able to make in the community. I’m proud to continue this journey with my teammates, our incredible fans and the city I love. Together, we’re building something special, and I’m excited for what’s ahead.”

The team’s long-time captain will continue to be a veteran presence in the locker room and on the soccer field, helping provide leadership to an increasingly young roster. Playing both centerback and left back over the years, Barnes has been a key figure on the Reign’s defense, which has been one of the stingiest in the league until last year. In 2016, Barnes was named NWSL Defender of the Year – helping the Reign earn eight clean sheets in their 20-game season and set a new NWSL record for consecutive shutouts (5).

She was named to the NWSL Best XI First Team in 2015 and 2016 and earned Best XI Second Team honors in 2014 and 2019. In three separate years (2019, 2022, and 2023), Barnes finished the NWSL season in the top 10 in the number of dribblers tackled. She also was in the top five in interceptions in 2023. As one of the core leaders on the team, Barnes has helped the Reign earn three NWSL Shields (2014, 2015, 2022), advance to three NWSL finals (2014, 2015, 2023), and play in seven NWSL semifinal matches.

“We are absolutely thrilled to welcome Lu Barnes back to the Reign this season,” said Reign General Manager Lesle Gallimore. “From the very beginning, Lu has been the heart and soul of this club, and her legacy here is unparalleled. As a world-class defender and leader in the NWSL, her influence extends far beyond the field. We are excited to see the immense impact she will continue to have on our team and the Reign community this season.”

In addition to her strong defensive chops, Barnes has been important to how the Reign builds their attack from the backline. Last year, the Reign struggled to break down presses, which has been one of Barnes’ strengths in the NWSL. In 2023, for example, she completed the third-most passes into the final third and had the seventh-most touches. While it doesn’t always show up in stats this clearly, this is a truly underrated part of Barnes’ skillset.

While Barnes dealt with injuries and health challenges in 2024, she still played nearly 1,500 minutes and made 21 appearances. As June/Ash Eden highlighted in the 2024 Valkyratings, like many Reign players last season, Barnes had mixed performances throughout the year. She has great field vision and is often the one communicating with and leading the backline, but she was prone to a few costly mistakes. While Barnes might not be a regular starter in 2025, she should continue to provide veteran leadership and mentor young defenders like Jordyn Bugg.

The club veteran has also established important roots in the region. She’s been active in environmental efforts in the Pacific Northwest and other community outreach activities led by the Reign and Seattle Sounders. Last fall, she joined current and former Reign teammates Olivia Van der Jagt, Fishlock, and Sam Hiatt in becoming part of the ownership group of Salmon Bay FC, Ballard’s new pre-professional women’s soccer team that will compete in the USL W League this spring.

The Reign captain has been involved in several other community efforts. Barnes has pledged 1% of her salary toward Common Goal to fund the growth and development of Football For Her, a California-based nonprofit that provides safe spaces for youth who identify as female or nonbinary to play soccer. She also works with Players for the Planet, an organization of professional athletes who are striving to make a difference by eliminating plastic, creating recycling initiatives and prioritizing conservation efforts.

The California native attended UCLA (2007-10), where she started in 95 of 97 games played and led the Bruins in assists in back-to-back seasons as a junior and senior.

Seattle, WA

SPD sees major hiring boost in 2024 with 84 new recruits

SPD new hires train after successful recruitment year

The Seattle Police Department may finally be turning the corner on its staffing struggles, as 2024 turned out to be one of their biggest recruitment years, with 84 new hires.

SEATTLE, Wash. – The Seattle Police Department is making strides in rebuilding its ranks after several challenging years. In 2024, the department achieved a major milestone, hiring 84 new officers—a significant boost as SPD works to address staffing shortages.

The hands-on training at the academy is designed to prepare student officers for the complex realities of policing, from pain compliance techniques to firearms proficiency.

“It’s serious, the responsibility we have and the trust that we’re given. We don’t want to hurt people unnecessarily,” said 24-year-old recruit Natalie Cornwall.

Cornwall, a Seattle native, returned to Seattle this past summer after applying to the department. She brings with her a background in the military, as her father served in the armed forces. Cornwall also has prior experience with Lacey’s Explorer program, where she participated for four years before aging out at 21.

“I just really missed the kind of sense of purpose on military bases,” Cornwall said. After traveling and completing college, she decided to pursue her passion for public service. “It’s about being part of something bigger than me and doing something that matters,” Cornwall said.

Seattle police, mayor celebrate hiring surge

Seattle Police and the Mayor’s Office are celebrating what they’re calling a surge in officer recruitment.

For another recruit, the journey to SPD marked a significant career shift. Damaris Dominguez, a 39-year-old mother from the Bronx, transitioned from the dental field to law enforcement.

“It was my first choice,” Dominguez said. Dominguez, who will turn 40 next month, said it was a choice she made after doing extensive research into the department. “I saw they were understaffed, just applied, I said I’m going to give it a go and I think it was the best choice,” Dominguez said. “As each step progressed, I started passing, getting calls, and I was like, ‘I’m in.’ It was a sign that I should be doing this.”

Dominguez views her new role as an opportunity to rebuild trust between police and the community. “It’s important to me because we’ve had a downfall in some years. Just being able to support our community…if it can be just a small change, that means everything,” she said.

As a Spanish speaker, Dominguez believes her language skills will be invaluable in connecting with Seattle’s diverse community. “It would be a big help because a lot of situations come from the lack of communication. Sometimes they can be misunderstood, so the fact that I can speak Spanish is going to be a big help when I’m on my beat,” Dominguez said.

The SPD hiring process is rigorous, involving multiple evaluations and months of training. Recruits spend 8-9 weeks at the post-basic academy, followed by additional field training.

Lieutenant Larry Longley, a field training officer with SPD, is optimistic about the department’s recruitment efforts. He noted an influx of candidates from across the country and military backgrounds.

“Some things have changed around the country. Crime’s at a pretty high level, so they’re seeing the necessity for it,” Longley said. He also credited social media for attracting interest in law enforcement careers.

SPD aims to hire 120 to 140 officers in 2025, surpassing 2024’s numbers.

“We need them now more than ever,” Longley said. “They’re going to be highly trained officers and professional officers.”

Despite this recruitment success, Longley noted that the department still faces challenges. “We lost quite a few officers, and we still have to factor in attrition numbers to even retiring,” Longley said. “It’s still years away, several years away, before we’re fully staffed.”

For Cornwall and Dominguez, joining SPD is more than just a career—it’s a calling. “It’s a lifestyle. It’s not just a career,” Cornwall said.

SPD Hires by the numbers

- 2024: 84

- 2023: 61

- 2022: 58

- 2021: 81

- 2020: 51

- 2019: 108

Individuals who have left SPD (Sworn + recruits)

- 2024: 83

- 2023: 97

- 2022: 159

- 2021: 171

- 2020: 186

- 2019: 92

Retirements

- 2024: 39

- 2023: 66

- 2022: 88

- 2021: 100

- 2020: 71

- 2019: 45

Seattle Police says Mayor Bruce Harrell aims to have the department back to pre-pandemic levels of around 1,400 officers.

BEST OF FOX 13 SEATTLE

Washington sees record eviction filings in 2024: ‘Not just an isolated incident’

New 2025 laws that are now in effect in WA

Good Samaritan saves mom from road rage incident in WA

Here’s when you’ll need REAL ID to go through US airport security

REI exits ‘Experiences’ businesses, laying off hundreds of employees

To get the best local news, weather and sports in Seattle for free, sign up for the daily Fox Seattle Newsletter.

Download the free FOX Seattle FOX LOCAL app for mobile in the Apple App Store or Google Play Store for live Seattle news, top stories, weather updates and more local and national coverage, plus 24/7 streaming coverage from across the nation.

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg) Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoMeta is highlighting a splintering global approach to online speech

-

Science4 days ago

Science4 days agoMetro will offer free rides in L.A. through Sunday due to fires

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoLas Vegas police release ChatGPT logs from the suspect in the Cybertruck explosion

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies’ Review: Thai Oscar Entry Is a Disarmingly Sentimental Tear-Jerker

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoMichael J. Fox honored with Presidential Medal of Freedom for Parkinson’s research efforts

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: Millennials try to buy-in or opt-out of the “American Meltdown”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPhotos: Pacific Palisades Wildfire Engulfs Homes in an L.A. Neighborhood