Seattle, WA

Seattle’s pathway to public power – Powerlines

Annually, the primary week in October is ready apart to acknowledge the various contributions made by the general public energy utilities that present dependable electrical energy on a not-for-profit foundation to 49 million People on daily basis. As Public Energy Week (Oct. 2 – 8) involves an in depth, we glance again on Seattle Metropolis Mild’s beginning, the early energy struggles, and the utility’s decades-long drive to turn out to be Seattle’s supplier of public energy.

Seattle’s streets aglow

Seattle’s path to public energy dates again to the Metropolis’s 1869 constitution, authorizing the municipal authorities to offer lighting for the streets. However it might be a number of years earlier than streetlights (powered by coal gasoline) brightened a handful of metropolis streets.

It wasn’t till 1886 that an electrical incandescent gentle bulb flickered to life for the primary time in Seattle (and west of the Rocky Mountains). Present was provided by a steam-powered generator put in by brokers of Thomas Edison who quickly fashioned the Seattle Electrical Mild Firm (a non-public firm unaffiliated with Metropolis Mild) and gained the primary municipal franchise to offer electrical energy for lighting public streets.

Energy from water

In June 1889 when the Nice Hearth devastated downtown, it was revealed the Metropolis’s privately owned water provider was less than the duty. The fireplace made it clear that Seattle wanted an plentiful water supply, and that the Metropolis wanted to supervise its distribution. A month later, a lopsided majority of 1,851 voters to 51 licensed the Metropolis to faucet the distant Cedar River. A yr later, voters established a municipal water division, step one towards creating a public utility system.

Within the wake of the hearth, small-scale electrical energy suppliers nonetheless marketed their companies to the rebuilding metropolis, however their charges had been astronomical. In late 1895, voters authorised bonds for the event of the Cedar River as a water supply (hydroelectricity got here later). Celebrated Metropolis Engineer R.H. Thomson took the lead on the event of the Cedar River watershed. And since Seattle could be tapping the river for its public water wants, why not construct a hydroelectric plant as a supply of electrical energy, too?

Over the following decade, technological advances allowed for electrical energy to journey longer distances than ever earlier than. In 1896, voters amended the Metropolis constitution to permit for the development of a municipal lighting plant at Cedar River. But it surely wasn’t till the election of 1902, when Seattle voters authorised the bonds wanted to construct the Cedar River hydroelectric facility, that the dream of public energy actually started to take form.

Seattle Metropolis Mild is born

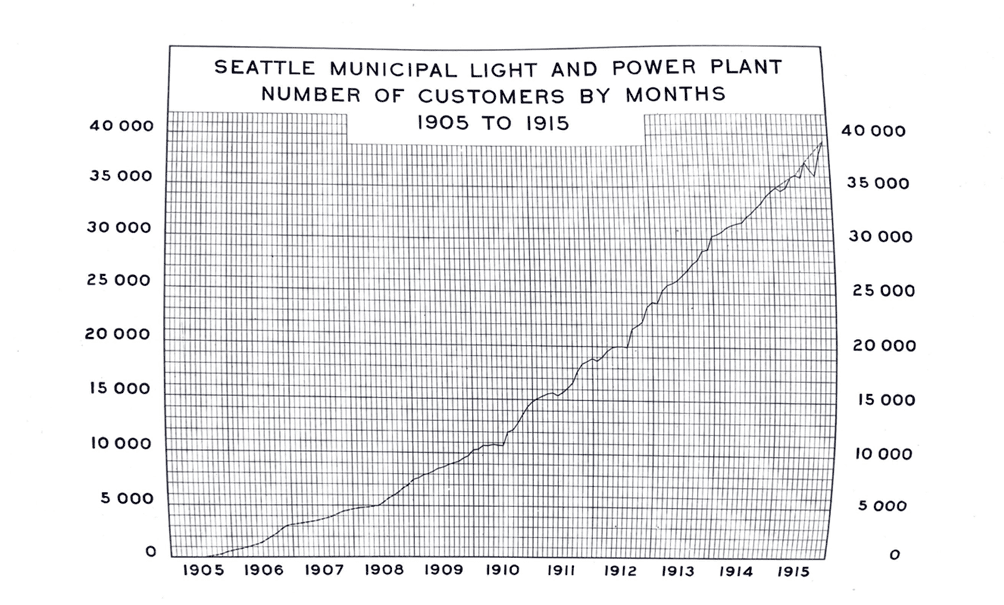

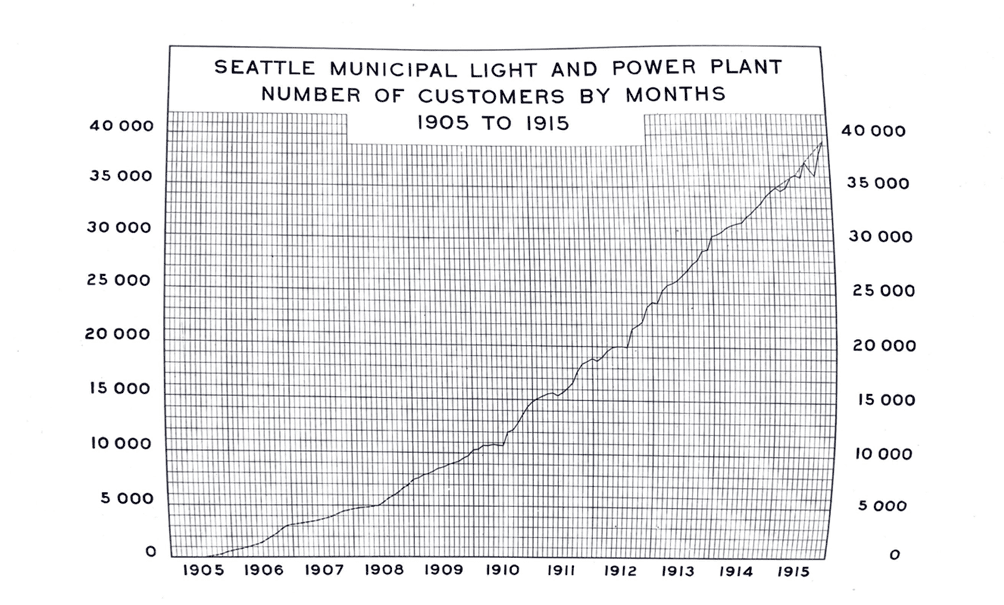

J.D. Ross, a steam engineer self-educated within the science of electrical energy, took over the Cedar Falls venture in early 1903. On Jan. 10, 1905, the primary present traveled 36 miles to a Seattle substation. Beneath the management of the Metropolis Water Division, the ability plant started delivering public energy to the streets of Seattle, growing the demand for municipal energy and forcing personal energy firms to chop their charges. The Water Division took possession of the personal Seattle Electrical Firm’s road lighting system on in January 1905. The primary industrial buyer linked was in April 1905. By September, basic purposes for gentle and energy opened to the general public. The demand for energy rose so dramatically that the Seattle Metropolis Council created a separate Division of Lighting – Seattle Metropolis Mild in 1910.

1914-15 Biennial Report from the Metropolis of Seattle Lighting Division – Seattle Municipal Archives: Seattle Lighting Division Data (Sequence III) Sequence Identifier: 1200-03

Energy struggles

The Metropolis was not the only real supplier of electrical energy throughout this era; its major competitor was Seattle Electrical. The personal firm grew within the early 1900s by shopping for quite a few small personal energy firms and finally merged with different regional energy suppliers to turn out to be Puget Mild & Energy. A battle between Seattle’s private and non-private energy suppliers occurred over 40 years.

In 1911, Ross – Cedar Falls chief electrical engineer – was appointed to move the Division of Lighting (aka Metropolis Mild). Typically referred to as the “Father of Metropolis Mild,” Ross was an aggressive proponent of public energy and would occupy the place for 28 years. In 1917, he obtained a federal allow to broaden Metropolis Mild’s hydroelectric technology capabilities by constructing services on the Skagit River – which over the following many years grew to a sequence of three dams. On Sept. 17, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge pressed a gold key within the White Home and formally began the mills for Gorge Dam (the venture’s first dam) sending electrical energy to Seattle 100 miles away.

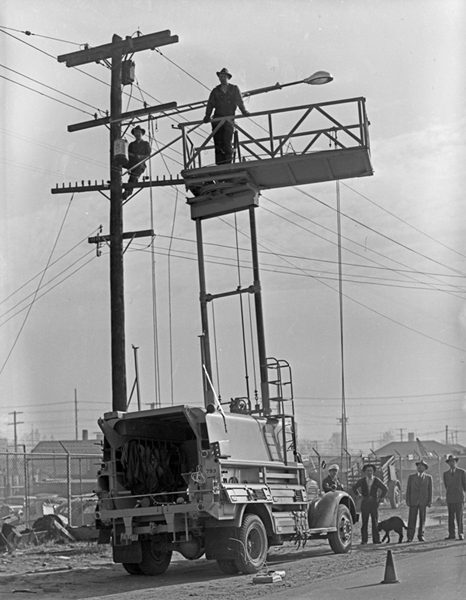

Seattle Municipal Archives Picture 2987

Ross’ victory on the Skagit within the Nineteen Twenties positioned Metropolis Mild as a contender for sole provider of electrical energy to Seattle. Within the ensuing many years, Metropolis Mild and Puget Energy competed economically and politically till Nov. 7, 1950, when Seattle voters authorised – by a razor-thin margin – a buy-out (to the tune of $25.8 million) of the privately owned Puget Powers’ Seattle territory. Seattle lastly had a unified energy system underneath one utility. Since then, Metropolis Mild has been Seattle’s unique electrical energy supplier, whereas Puget Energy – identified at present as Puget Sound Vitality – went on to concentrate on powering the suburbs.

Powering the longer term

Seattle Municipal Archives Picture 43221

At this time, Metropolis Mild is powered by about 1,600 staff, seven hydroelectric vegetation and 16 main substations. The utility serves greater than 426,000 residential clients, and about 51,000 industrial and industrial clients.

Metropolis Mild has lengthy been powered by creativity and innovation, and creating the utility of the longer term requires us to construct on the successes of our previous. At this time, the utility’s carbon-neutral vitality portfolio produces environmentally accountable, protected, low-cost, and dependable energy. Nonetheless, we’re within the midst of one other main vitality trade transition that continues to evolve together with our clients’ wants. The worldwide shift to a lower-carbon vitality system is accelerating, and public energy suppliers are positioned to adapt to a quickly altering vitality panorama.

Seattle, WA

Blue Angels prep for Seafair show with early landing in Seattle

One of the U.S. Navy’s famous Blue Angels landed Monday afternoon in Seattle, more than half a year ahead of the famous squadron’s annual air show at Seafair.

Descending through a low-hanging blanket of grey skies around 2 p.m., the Blue Angel No. 7 jet landed at Boeing Field with a small crowd of Seafair executives and news crews gathered to greet them. One photographer jokingly asked the two pilots if they’d done any barrel rolls on their flight from Oakland, Calif.

“You can get in trouble doing some of that stuff, so we don’t do that,” said U.S. Marine Corps Maj. Scott Laux through a smile. “But admittedly, it’s the greatest window seat that you’ll ever get. We were admiring the mountains all the way up, the beautiful snow-capped mountains all the way up the coast.”

One of the Blue Angels has landed at Boeing Field in Seattle.

The pilots are here to prep for Seafair this summer. pic.twitter.com/5UYyM6T3XD

— Sam Campbell (@HeySamCampbell) January 13, 2025

U.S. Navy Lt. Commander Lilly Montana sat in the cockpit seat behind Laux. She told KIRO Newsradio Washingtonians can expect a much more exciting entrance at Seafair than she and Laux had to resort to Monday.

“The type of flying is certainly going to be different,” Montana said, adding that the low cloud cover meant they couldn’t follow through on some preplanned theatrics Monday.

Just interviewed the pilots, Lt. Commander Lilly Montana and Maj. Scott Laux.

I’ll have more on @KIRONewsradio 97.3FM https://t.co/IlB9uSBXf5 pic.twitter.com/D9Qa63pTcw

— Sam Campbell (@HeySamCampbell) January 13, 2025

“Not as exciting of an arrival as you’ll see out of the six-plane delta here at the end of July,” she said. “They’ll come in for what’s known as the pitch-up break. That is an overhead maneuver with all six jets flying very close together, smoke on – very exciting to see.”

Montana and Laux will spend about a day in Seattle coordinating with airshow and Seafair planners for the demonstration.

The 2025 Boeing Air Show at Seafair is scheduled to take place between Aug. 1 and 3.

Sam Campbell is a reporter, editor and anchor at KIRO Newsradio. You can read more of Sam’s stories here. Follow Sam on X, or email him here.

Seattle, WA

‘Hidden Yards Lost’ also hurt the Seahawks as much as turnovers

Occasionally, football coaches will talk about something called “Hidden Yards Lost.” These are the plays that did meaningfully affect the football game, but you won’t find them reflected anywhere because another event on the field made it so that play never existed.

In short, these are the big plays that get erased by a penalty.

I went through all 17 games from the Seattle Seahawks this season and tracked the yards that were lost because of penalties.

Below are the results. If you’d like to know the greatest offender, I can tell you it is…

at the conclusion of this post.

Here are the rules and initial guidelines:

Rules and Guidelines for Invisible Yards Lost

- This seeks to measure the difference between what a play would have gained, against where the ball ultimately ended up because of lost yards due to penalty. For example, a 10 yard gain negated by an offensive holding penalty would be a total of 20 “Hidden Yards Lost”

- A false start, a defensive hold, an offsides, and other infractions that either kill the play or simply result in X yards plus new set of downs are not the objective in Hidden Yards Lost

- This will overwhelmingly appear to be the fault of the offense. Reason being, a defensive penalty adds yards in the same direction as the ball is headed, while offensive (and certain special teams) penalties are what move the ball against where it was originally headed.

- Of those, the primary offender are perimeter holding calls. Again, makes sense, as those are often isolated engagements in full view of an official.

- There were some surprises.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25829289/Screenshot_2025_01_12_at_9.52.30_PM.png)

At this point in the season, it appears as if Anthony Bradford might be the worst player in football. I remain shocked that he was given so much time to sow chaos among his brethren linemen before finally a fresh face entered the mix.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25829291/Screenshot_2025_01_12_at_9.53.50_PM.png)

Leonard Williams makes an appearance as the first defensive player to join the fray. That play was so bonkers the entire Seattle beat had to look it up and write about it all evening. Even though there was a false start, the play bizarrely continued just long enough for Big Cat to facemask a dude. As we learned – twice(!) this season, a personal fall supersedes a lesser penalty. Therefore, instead of five yards backwards it was 15 yards forward for the San Francisco 49ers.

Kenneth Walker…woof.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25829295/Screenshot_2025_01_12_at_9.57.01_PM.png)

Derick Hall was having so much fun.

Two roughing the passer penalties destroyed negative plays on the offense, while Devon Witherspoon cancelled out a big sack, and Jerrick Reed threw his hat in for the big special teams field position cancellation.

Not to be outdone, Mike Jerrell lost an entire football field in two plays.

Week 10 had nothing, followed by the bye week.

We resume:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25829305/Screenshot_2025_01_12_at_10.01.17_PM.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25829306/Screenshot_2025_01_12_at_10.01.43_PM.png)

Week 18 had nothing to report

Results

Here are the biggest yard-subtractors, in order:

- Mike Jerrell: 98

- DK Metcalf: 72 and a TD

- AJ Barner: 64 and a TD

- Pharaoh Brown: 58

- Kenneth Walker: a 57-yard TD

Notes –

- Leonard Williams will get the nod for most defensive yards lost at 49, which surprised me because of how well he played this season. It was the result of three very unfortunately-timed plays.

- Anthony Bradford: at just 40 yards and a safety didn’t even finish the season in the top five. There were even a couple other players in the fifties.

- I’m not going to conclude the same thing about DK Metcalf that I some people will. For starters, the offensive pass interference calls are for him blocking while another receiver got the ball. I have long been a proponent that Metcalf receives a disproportionate amount of physical calls against him because of his size and aura, especially weighed against the physical calls that are not called in his favor. The dude is big and easy to see. I will admit the volume of those is alarming, and if somebody insists on continuing to try screen plays in the future, they’ve got to figure out how to help Metcalf out here.

ONE FINAL NUMBER

In total, the Seahawks lost 802 yards and three touchdowns in the 2024 season that will never show up on the stat sheet. Erased from time, almost like the picture of Marty McFly’s family in Back to the Future.

Seattle, WA

Seattle’s Little Free Libraries Offer a Catalog of Collections and Connections

Spooning buttercream into a pastry bag, Kim Holloway is close to opening time. She pipes rosettes of frosting on trays of vanilla cupcakes—some plain vanilla frosting, some cookies and cream.

With the aid of Holloway’s “partner in crime,” Kathleen Dickenson, they prop the lid of an old-fashioned school desk in Holloway’s front yard and fill it with cupcakes. Holloway adds edible pearls and glitter. Shortly after 3 p.m., the Little Free Bakery Phinneywood is open for business—the business of sharing.

“I love to bake, and many people have told me, ‘Oh, you should open a bakery.’ And I just think, ‘No, no, no, no. It would take the joy out of it for me,” Holloway says.

“To me, the seed library is part of food security. It’s like having money in the bank, but it’s seeds in the library.”

Like hundreds of other Little Free hosts in the region, she’s found joy instead in giving.

And, like so many good ideas, this one started with a book.

In 2009, a Wisconsin man named Todd Bol built a Little Free Library in his front yard, encouraging passersby to take a free book or drop off extras. The idea and the format—a wooden box set on a post, usually with a latched door—seeded a movement, with more than 150,000 registered worldwide.

“Seeded” got literal fast: The Little Free book idea spread to other sharing opportunities, including a rampant crop of Little Free Seed Libraries, where people swap extra packets of cilantro and Sungolds.

Seattle’s density, temperate climate, walkable neighborhoods—and maybe our introvert culture?—make it easy for the little landmarks to thrive. They exploded during the COVID-19 pandemic, when locals thought outside the box by putting up a box, including what’s believed to be the nation’s first Little Free Bakery and first Little Free Art Library. Many built on the region’s existing affinity for hyperlocal giving—the global Buy Nothing phenomenon, for one example, was founded on Bainbridge Island.

“We just seem to do more of all these versions of sharing,” says “Little Library Guy,” the nom de plume of a longtime resident who showcases the phenomenon on his Instagram feed and a helpful map.

The nonprofit organization now overseeing global Little Free Libraries finds the nonbook knockoffs “fun and flattering,” communications director Margret Aldrich says in an email. (She also notes “Little Free Library” is a trademarked name, requiring permission if used for money or “in an organized way.”)

Some libraries stress fundamental needs: A recently established Little Free Failure of Capitalism in South Seattle provides feminine products, soap, chargers, even Narcan. A Columbia City Little Free Pantry established by personal chef Molly Harmon grew into a statewide network for neighbors supporting neighbors.

Others are about the little things: Yarn. Jigsaw puzzles and children’s toys. Keychains (one keychain library in Hillman City has a TikTok account delighting 8,000+ followers). A Little Free Nerd Library holds Rubik’s Cubes and comic books.

Regardless of where each library falls on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, they stand on common ground. “There’s a line from [Khalil] Gibran: ‘Work is love made visible,’ ” Little Library Guy says in a phone call. “That’s what they’re doing. They’re showing that they love the community by doing something for them.”

Here’s a little free sample of what you might find around town:

Seeding a Movement

Two University of Washington students sort, count, and bag mammoth sunflower seeds during an annual seed inventory inside a research facility at the Center for Urban Horticulture. These are seeds that birds at the UW Farm did not get to, and they’ll go into the Little Free Seed Library by the end of the day. (Photo credit: Ken Lambert/The Seattle Times)

At the UW Farm, on 1.5 acres of intensively planted land at the Center for Urban Horticulture, students grow more than six tons of organic produce annually. They learn about agriculture and ecology while providing food for 90 families in a neighborhood CSA, for college dining halls and for food banks.

One chilly November day, students and volunteers on the self-sustaining farm worked with the small staff to inventory what seemed like countless seeds for next year’s plantings: Parade onions, Autumn Beauty sunflowers, Painted Mountain corn, Genovese basil. Packs with just a small number of remaining seeds were set aside for the Little Free Seed Library installed near rows of winter greens.

Farm manager Perry Acworth organized the little library during the pandemic, seeing the renaissance in home gardening coupled with a run on supplies. “Seeds were sold out … even if they had money, they couldn’t find them,” she says.

Acworth picked up a secondhand cabinet—one with a solid door, rather than the usual Little Free Library glass window, because seeds need to be protected from light. Althea Ericksen, a student at the time, designed it, painted it with a cheerful anthropomorphic beet, and installed it.

Seeds were packed inside jars to protect them from rodents and birds who otherwise would have a feast, and the Little Free Seed Library was born—shielded from rain and direct sun, convenient to pedestrians as well as cars.

On a recent day, seeds for radish, mizuna, red cabbage, and flashy troutback lettuce waited in lidded jars for their new winter homes.

On the side of the seed library, thank you notes sprout comments such as, “Thank you for sharing.” Enough harvests have gone by to see the library’s benefits, from flowering pollinators to harvests of food. A mere handful of seeds isn’t useful for the farm’s scale, Acworth notes, but for library guests, “If I have five sunflowers in my yard, five heads of lettuce, that’s great.”

It isn’t all sunflowers and appreciation. The library has been emptied more than once; the seeds were once dumped out and used to fuel a fire on the ground.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWho Are the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom?

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg) Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoMeta is highlighting a splintering global approach to online speech

-

Science3 days ago

Science3 days agoMetro will offer free rides in L.A. through Sunday due to fires

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSeeking to heal the country, Jimmy Carter pardoned men who evaded the Vietnam War draft

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png) Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoLas Vegas police release ChatGPT logs from the suspect in the Cybertruck explosion

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies’ Review: Thai Oscar Entry Is a Disarmingly Sentimental Tear-Jerker

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump Has Reeled in More Than $200 Million Since Election Day