Colorado

Colorado House passes bill banning so-called assault weapons

DENVER — Democrats in the Colorado House of Representatives passed a bill on Sunday that would ban so-called assault weapons.

House Bill 1292 passed largely along party lines on a 35-27 vote. It now heads to the state Senate.

HB24-1292, which is sponsored by State Reps. Elisabeth Epps and Tim Hernandez, would define “assault weapon” and ban the manufacture, import, sale, or purchase of such weapons in Colorado.

The bill would also ban the possession of rapid-fire trigger activators, which are devices that can be attached to a gun to increase the speed at which it fires.

Hernandez said Friday his background as a teacher and as the first Colorado state lawmaker from Gen Z (the generation born between 1997 and 2012) provides him with a perspective on guns that differs from most of his colleagues.

“We have been living with mass shootings for my entire life. We have been doing active shooter drills for my entire life. We have been waiting to die in schools because adults would not be bold enough on guns,” said Hernandez. “Then I finally became a teacher, and I sat with my students who were still afraid to die in schools because adults would still not be bold enough on guns.”

Republican lawmakers like State Rep. Matt Soper told Denver7 on Friday the bill violates the Second Amendment rights of Coloradans.

“I can tell you from rural Colorado, the one thing that people hold most dear would be their property and firearms are right there with it,” Soper said. “Firearms are very symbolic of our way of life, of who we are.”

State Rep. Richard Holtorf, a Republican who’s also running for Congress in the Fourth Congressional District, said he doesn’t believe many sheriffs in Colorado will enforce the legislation, should it become law.

“You need to understand that in the 64 counties, I would opine that about 47 of them will never, ever because of those to the Constitution enforce this statute,” said Holtorf.

The County Sheriffs of Colorado opposes the bill.

Its future in the Senate, where more moderate Democrats serve, is unclear.

The Follow Up

What do you want Denver7 to follow up on? Is there a story, topic or issue you want us to revisit? Let us know with the contact form below.

Colorado

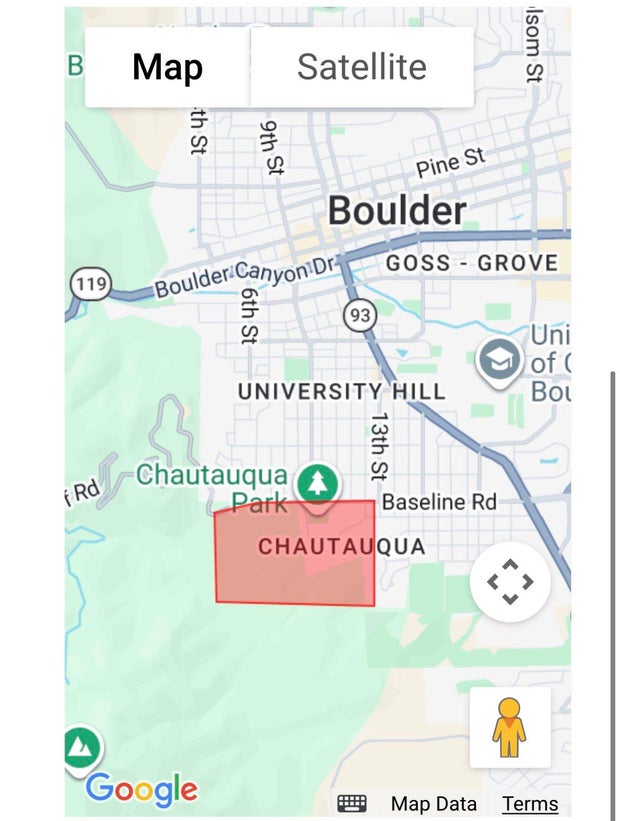

Evacuation warning issued for area near wildfire in southwest Boulder

Authorities have issued an evacuation warning for homes near a wildfire that broke out in southwest Boulder on Saturday afternoon.

Just before 1 p.m., Boulder Fire Rescue said a wildfire sparked in the southwest part of Boulder’s Chautauqua neighborhood. The Bluebell Fire is currently estimated to be approximately five acres in size, and more than 50 firefighters are working to bring it under control. Mountain View Fire Rescue is assisting Boulder firefighters with the operation.

Around 1:30, emergency officials issued an evacuation warning to the residents in the area of Chatauqua Cottages. Residents in the area should be prepared in case they need to evacuate suddenly.

Officials have ordered the DFPC Multi-Mission Aircraft (MMA) and Type 1 helicopter to assist in firefighting efforts. Boulder Fire Rescue said the fire has a moderate rate of spread and no containment update is available at this time.

Red Flag warnings remain in place for much of the Front Range as windy and dry conditions persist.

Colorado

Two-alarm fire damages hotel in Estes Park, 1 person taken to a Colorado hospital

A two-alarm fire damaged a hotel in Estes Park on Friday night. It happened at Expedition Lodge Estes Park just north of Lake Estes.

The lodge, located at 1701 North Lake Avenue on the east side of the Colorado mountain town, was evacuated after 8:30 p.m. and the fire chief said by 10 p.m. the fire was under control.

One person was hurt and taken to a hospital.

The cause of the fire is under investigation. So far it’s not clear how much damage it caused.

A total of 25 firefighters fought the blaze.

Colorado

Warm storm delivers modest totals to Colorado’s northern mountains

Lucas Herbert/Arapahoe Basin Ski Area

Friday morning wrapped up a warm storm across Colorado’s northern and central mountains, bringing totals of up to 10 inches of snowfall for several resorts.

Higher elevation areas of the northern mountains — particularly those in and near Summit County and closer to the Continental Divide — received the most amount of snow, with Copper, Winter Park and Breckenridge mountains seeing among the highest totals.

Meanwhile, lower base areas and valleys received rain and cloudy skies, thanks to a warmer storm with a snow line of roughly 9,000 feet.

Earlier this week, OpenSnow meteorologists predicted the storm’s snow totals would be around 5-10 inches, closely matching actual totals for the northern mountains. The central mountains all saw less than 5 inches of snow.

Here’s how much snow fell between Wednesday through Friday morning for some Western Slope mountains, according to a Friday report from OpenSnow:

Aspen Mountain: 0.5 inches

Snowmass: 0.5 inches

Copper Mountain: 10 inches

Winter Park: 9 inches

Breckenridge Ski Resort: 9 inches

Arapahoe Basin Ski Area: 8.5 inches

Keystone Resort: 8 inches

Loveland Ski Area: 7 inches

Vail Mountain: 7 inches

Steamboat Resort: 6 inches

Beaver Creek: 6 inches

Irwin: 4.5 inches

Cooper Mountain: 4 inches

Sunlight: 0.5 inches

Friday and Saturday will be dry, while Sunday will bring northern showers. The next storms are forecast to be around March 3-4 and March 6-7, both favoring the northern mountains.

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana6 days ago

Louisiana6 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO3 days ago

Denver, CO3 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT