North Carolina

North Carolina Is a Warning

The advert that signaled the approaching disaster for democracy in North Carolina appeared simply 4 days earlier than the November 2012 election. Because the advert opened, a lady’s voice questioned aloud whether or not voters “can belief Sam Ervin IV to be a good choose.” Ervin, captured in black and white, appears shifty, transferring his eyes backwards and forwards earlier than turning his head immediately as if he’s on the run. Ervin and his household, the advert introduced, had donated to the marketing campaign of the previous Democratic governor, and later convicted felon, Mike Easley. The digicam lingers on Ervin’s face because the advert explains that he went on to get a $100,000 state job; the portrait may very well be mistaken for a mug shot, have been it not for his go well with and tie.

One may need assumed that Ervin was working for top federal workplace, given the seriousness and slickness of the advert—and the truth that the group liable for it was largely funded by a nationwide Republican PAC. However no, Ervin was working for one seat of seven on the state supreme court docket. When Election Day arrived, he misplaced to Paul Newby, who’s now North Carolina’s chief justice. (In 2014, Ervin received a seat on the court docket too.)

This advert within the Newby-Ervin race augured a basic change within the politics of North Carolina’s judiciary. Simply eight years prior, the state had made judicial elections nonpartisan and created the nation’s first public-funding system for judicial elections. This advert introduced the worst of the political system again into judicial races: blatant manipulations of details to suggest that Ervin had gotten his job as a result of he had given a bribe (he hadn’t), ominous tones and destructive spins that performed to voters’ feelings, and a mysterious political group backed by unknown funders. North Carolina had tried to take the judiciary out of politics—and politics out of the judiciary—however its reforms have been no match for the flood of cash in politics following Residents United and Republican efforts to take over the courts after the Tea Social gathering wave. Quickly thereafter, the period of tried judicial reform in North Carolina formally ended. The legislature eradicated public funding simply months after the 2012 election and later made judicial elections partisan but once more.

Subjecting state judiciaries to the kind of uncooked politics exemplified in that advert—and making them beholden to partisan, privately funded elections—creates an inconceivable state of affairs for judges. They’re compelled to marketing campaign as a member of a celebration, which means their funds and help come from the identical politicians and donors whose instances they have to hear as soon as elected. Over time, their electoral victories and profession longevity depend on the favor and success of their get together and its leaders.

The express intermingling of judges’ skilled obligations and private pursuits makes serving as a co-equal test on the opposite branches of presidency infinitely extra advanced. Politicians can then exploit the court docket’s politicization for their very own goals, additional undermining the judiciary within the course of. For instance, if a choose points an opinion {that a} politician disagrees with, an elected consultant can use the truth that judges are a part of the political fray to justify direct assaults on the judiciary, whether or not they’re private (towards a selected choose) or systemic (on judicial energy) in nature.

This dynamic is at its most harmful with regards to election legislation, the place it threatens the legitimacy of the American electoral system in its entirety. Due to John Roberts’s ruling in North Carolina Republicans’ favor in Rucho v. Frequent Trigger in 2019, state courts at the moment are the one out there judicial arbiters for partisan gerrymandering claims. Gerrymandering particularly presents a major downside for elected state courts. Judges’ legitimacy depends upon their perceived objectivity, and so sticking a D or an R subsequent to their identify at all times threatens the general public belief in them. This belief is very vulnerable to being misplaced when judges should explicitly rule on whether or not their very own get together can or can’t favor itself in an election, as they do in redistricting instances. However the issue right here isn’t just optical; judges the truth is might face important stress from the political system to rule in favor of their get together for no motive aside from loyalty.

The blending of gerrymandering and judicial politics has created a democratic doom loop in North Carolina. The legislature is leaving the court docket with no good choices: give in and grant the legislature the map it needs, or maintain quick however face Republicans’ efforts to assault the present court docket as hopelessly partisan and discover candidates who will likely be extra more likely to let the get together gerrymander freely.

That is an ominous signal for different states. With its even partisan break up, its historical past of racist insurance policies, and its stark urban-rural divide, North Carolina has proved to be a microcosm of nationwide conflicts earlier than.

North Carolina’s expertise portends two doable futures for democracy, and which path the nation takes from right here relies upon largely on the U.S. Supreme Courtroom.

In a single state of affairs, North Carolina is a blueprint for the opposite 37 states which have elections for his or her state supreme courts. State courts can be topic to variations of the assault advertisements, untraceable cash, and rank partisanship seen in that Ervin-Newby race.

Within the different, even darker future, North Carolina’s judicial politics and gerrymandering conflicts result in the basic remaking of election legislation for your entire nation. If the state’s Republicans get their method in a case now earlier than the Supreme Courtroom, they may safe a everlasting victory for his or her get together over Democrats, for legislatures over courts, and for partisanship over equity and accountability—not simply in North Carolina, however throughout your entire nation.

For many years, North Carolina has been house to a sequence of redistricting disputes. The U.S. Supreme Courtroom discovered within the Nineteen Nineties that politicians there had openly drawn a district to seize Black voters inside its strains, within the nation’s first judicially decided occasion of racial gerrymandering. Democrats managed the state for years earlier than and after that ruling, and so they gerrymandered Republicans ruthlessly, creating congressional districts that resembled snakes slithering by way of the state repeatedly so as to assure victory for his or her representatives.

After Republicans swept to victory in 2010, they used algorithms and new mapping expertise to gerrymander Black voters and Democrats out of energy so exactly and commonly that Democratic North Carolina Consultant David Worth, who had as soon as been pretty agnostic about redistricting reform, started to imagine that it was desperately wanted. “I started to suppose, That is simply not acceptable,” he informed me. “There must be some sort of coverage or authorized constraint.”

Extra not too long ago, and most important to this present second, the occasions in North Carolina following the 2019 Rucho determination have exemplified how gerrymandering and judicial politics reinforce one another and, in tandem, pose a broader threat to the democratic system in states all over the place.

Not lengthy after Roberts’s determination got here down, Newby (Ervin’s competitor within the 2012 race) ran for chief justice of North Carolina’s Supreme Courtroom towards Cheri Beasley (now a Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate), this time formally as a Republican. On this election, as Democrat-leaning teams spent tens of millions of {dollars} supporting Beasley, Newby himself jumped into the partisan fray.

Newby’s stump speech from that marketing campaign reads like an inventory of Republican politicians’ best hits. He referred to as Beasley an “AOC particular person” and joked {that a} gun rack was the perfect place for a marketing campaign bumper sticker. He championed the constructing of a border wall—by no means thoughts that state justices haven’t any position in constructing partitions, particularly in a state 1,500 miles from the border—and informed Democrats to get out of America in the event that they hated the American proper a lot.

Speeches like Newby’s—who received, though by simply 401 votes—bother U.S. Consultant G. Okay. Butterfield from North Carolina, a Democrat and a former member of the state’s supreme court docket himself. “After I served on the court docket, I skilled a modicum of restraint on the a part of my Republican colleagues on the supreme court docket,” he informed me. “Republican supreme-court justices now are the intense partisans.” John Szoka, a reasonable Republican North Carolina state consultant, shared related considerations with me in regards to the state’s Democratic justices. In a state the place they agree on little, at the very least some Republicans and Democrats discover the politicization of the state supreme court docket troubling.

That politicization was evident throughout Harper v. Corridor, the current gerrymandering case in North Carolina that occurred throughout the state court docket system. Republicans drummed up the nuclear chance of impeaching North Carolina Supreme Courtroom Justice Anita Earls if she didn’t recuse herself from Harper v. Corridor, as a result of she had labored beforehand as an lawyer at one of many authorized teams bringing the case. In addition they mentioned that Ervin ought to recuse himself as a result of he was up for reelection. Democratic strategists countered {that a} Republican justice serving on the identical court docket, Phil Berger Jr., is the son of State Senate President Phil Berger Sr., who was a celebration to the litigation, and that he ought to recuse himself too. Not one of the justices recused themselves.

At oral argument, Newby didn’t conceal his perception that the judiciary ought to do nothing to cease Republicans’ redistricting methods that assure victory for them, going as far as to say of his state’s elections: “Now we have free. We don’t have truthful.”

Although he was distinguishing the language of North Carolina’s structure from different states’, Newby made clear that he wouldn’t block the legislature’s gerrymandered maps if he had a majority on his facet. This might imply, in a state that’s roughly one-third Democrats, one-third Republicans, and one-third Independents, Republicans would get 10 congressional seats and Democrats 4, whereas Republicans would seemingly have a 60 p.c supermajority in each chambers of the state legislature. The North Carolina Supreme Courtroom in the end prevented furthering the doom loop that point. Standing as much as the legislature, it held that partisan gerrymandering was a violation of 4 separate clauses of the state’s structure and that the Republican-drawn maps wanted to be redrawn accordingly.

This determination has hardly put the gerrymandering query to relaxation, nevertheless. Political insiders within the state predict that the 2022 judicial election will make 2012 and 2020 look tame as Republicans attempt to take management of the state court docket after which probably undo Harper v. Corridor, or at the very least approve of a brand new congressional map. More cash will circulate in, and the advertisements will solely get nastier.

The nation is already seeing echoes of North Carolina in judicial races and redistricting litigation elsewhere. Virtually $100 million was spent on state judicial campaigns nationwide within the 2019–20 election cycle, in contrast with $38.4 million in 2009–10. In Pennsylvania, house of one other important redistricting case, the Republican State Management Committee (which helped fund the group that ran the advert towards Ervin in 2012) spent greater than $500,000 on one state supreme-court race in 2021. In Wisconsin, political teams aside from the candidates spent $9 million for simply two seats within the 2019–20 cycle. And in Ohio, a Republican state-supreme-court justice dominated that the state legislature had violated the state’s structure by creating an excessively partisan map—solely to be met with defiance of her ruling and requires her impeachment from members of her personal get together.

Honest-maps reformers have had important victories this cycle. Not solely in North Carolina, but additionally in New York and Maryland, amongst others, state courts have reined in rank partisanship in map drawing, serving as a wanted test on their legislatures. However with these encouraging developments comes much more stress on these state supreme courts. “I feel, as these courts grow to be extra essential, and are listening to these very high-stakes instances, I feel the political temperature is more likely to rise. And that’s a priority for the integrity of our judicial system,” Alicia Bannon, an knowledgeable on state courts on the Brennan Heart, informed me.

However now, issues could take one other sudden flip. North Carolina Republicans, fearful that the courts might stand in the best way of their plans to carry on to energy within the state, have introduced a case to make the courts impotent within the election context.

Following the ruling in Harper that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional in North Carolina, the state’s Republican management turned to the U.S. Supreme Courtroom. Though the Courtroom didn’t instantly give the state’s Republicans the maps they wished, 4 justices strongly inspired North Carolina’s Republicans to attempt once more within the case (now often known as Moore v. Harper). This week, the Courtroom granted a listening to for the case in its subsequent time period.

North Carolina Republicans’ argument—often known as the independent-state-legislature idea—holds that state legislatures alone set the foundations of federal elections of their respective states, unbound by their state structure and courts and trumped solely by an act of Congress. The results in the event that they succeed can be far-reaching and devastating. The primary domino to fall can be that the state judiciary would haven’t any say within the congressional redistricting course of in North Carolina and theoretically every other state, regardless of how egregious the gerrymander. Voters denied equal illustration and a good system would have nowhere to show: not federal courts, due to Roberts’s ruling in Rucho; not state courts; and sure not the political course of itself, as a result of politicians in Congress and statehouses might, and possibly would, do all the pieces doable to make sure that their very own get together stays in energy.

The Courtroom might go even additional, although. Unbiased redistricting commissions may be banned for federal elections regardless of their significance in a variety of states. If the Courtroom each continues to intestine the Voting Rights Act, which seems seemingly, and takes North Carolina’s argument to the intense, voters of coloration might and possibly can be gerrymandered out of energy and denied the appropriate to vote in congressional and presidential elections with out safety from any court docket.

This doctrine has been met with skepticism even by some distinguished members of the conservative authorized and political communities. Ben Ginsberg, the famed GOP election lawyer, famous to me that even when the independent-state-legislature idea might succeed as an argument in sure election contexts, redistricting doesn’t seem like certainly one of them. Dallas Woodhouse, the previous govt director of the North Carolina Republican Social gathering who vehemently disagreed with the state’s supreme-court ruling that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional in North Carolina, was blunt with me: “The federal case is weak.”

John Roberts emphasised in his opinion in Rucho that plaintiffs might search reduction for partisan-gerrymandering claims in state courts at the same time as he mentioned that federal courts wouldn’t hear these instances. That the Courtroom would ignore its personal chief justice’s phrases in such a current, high-profile determination and throw out a number of precedents would have been seen as inconceivable even only a few years in the past.

However this isn’t a Supreme Courtroom unwilling to overturn precedent, a actuality that’s turning into clearer each week. The truth that 4 justices (Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, Clarence Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch) inspired North Carolina Republicans to attempt once more, and now have simply granted a full listening to for the case, seemingly signifies that they’re assured they’ve the 5 votes they want for a majority.

If the Courtroom in the end agrees with North Carolina’s Republicans, then all of us may be nostalgic for the times of judicial assault advertisements.

North Carolina

NC schools are struggling with segregation 70 years after Brown v. Board, new research shows

North Carolina schools — and schools across the nation — remain segregated and often are more segregated now than they were just a few decades ago, according to two new studies.

Friday marks the 70th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, in which the court ruled that laws racially segregating schools were unconstitutional and that separate facilities were inherently unequal.

The state and nation are more diverse now than in the 1990s. But while white students are now a minority of the state’s student traditional public school population, most white students still attend schools that are mostly white. At the same time, the average Black student attends schools that are disproportionately Black.

The changes are in part because of continued residential segregation, rising choices outside of the traditional school system and waning efforts to desegregate in the traditional public school system, researchers note. “Resegregation” of schools, then, is in part because of the loss of white students to other types of schools, like public charter schools.

“What we see in North Carolina is consistent with what’s happening in other parts of the nation,” said Jenn Ayscue, an assistant professor at North Carolina State University and co-author of one of the new studies that focused specifically on North Carolina. The study was done in partnership with the University of California-Los Angeles. “We did a similar report 10 years ago, and found that schools at that point were becoming more segregated. So in this last decade, it’s gotten even worse.”

The causes of the problem are often also out of the control of schools alone.

“Residential segregation has not gone anywhere in this country,” said Jerry Wilson, director of policy and advocacy at the Center for Racial Equity in Education, a Charlotte-based organization. “It remains and that’s the one that policymakers just seem unwilling to do much about. We’ve tinkered around with schools as a means of desegregating. But ultimately, our society and policymakers have proven unwilling to really address the heart of it, which is residential segregation.”

How segregated schools are can affect academic outcomes for the students who attend them, Ayscue said.

One of the reasons racial integration matters is that race often correlates with other meaningful demographic statistics, Ayscue said. In schools that were “intensely segregated” with students of color in 2021, 82.6% of the students were recipient of free or reduced-price lunch.

Intensely segregated refers to schools that enrolled 90% to 100% students of color. Students of color statewide comprise about 55% of the student population.

Ayscue said students tend to do better in schools where household incomes tend to be higher, although there are always outliers. More affluent schools tend to have fewer needs, more experienced teachers and less employee turnover.

During the 1989-90 school year, less than 10% of Black students attended a school that was intensely segregated with students of color. But during the 2021-22 school year, just under 30% of Black students did.

But white students are less likely now to attend schools that are intensely segregated with white students. During the 1989-90 school year, 21.6% of schools were intensely segregated with white students. But by 2021-22 school year, that was 1.9% of schools.

Integration is better in more rural school districts, where there aren’t as many schools. A single town might have only one school that all students attend, Ayscue said.

What can be done

Ayscue and her fellow researchers recommend expanding magnet school programs or other methods of offering a “controlled choice” for families. Magnet schools can take shape a few different ways but are essentially normal public schools with extra programming that outside families can apply to attend. They typically take neighborhood students and outside applicants. Because of that mix, they often are more diverse than other nearby schools.

Magnet schools are relatively rare, mostly concentrated in urban and suburban areas. North Carolina has 226 magnet schools this year, located in 17 school systems. Nearly all of the magnet schools are in Wake, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Durham, Guilford, Winston-Salem/Forsyth and Cabarrus county school systems. The state has 115 school systems and more than 2,600 schools.

NC State’s researchers found some school systems are working to reduce segregation at their schools. Durham Public Schools next year will start is “Growing Together” student assignment plan, a heavily debated major overhaul that creates sub-districts in which students can attend a neighborhood or magnet school and limits choice options across the system. Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools is studying its enrollment and attendance trends before creating a student assignment policy that would attempt to increase socioeconomic diversity at the district’s schools.

A national study from Stanford University and the University of Southern California pointed to charter schools are a reason for the resegregation. Charters can often be heavily segregated — attracting mostly white families in suburban areas or attracting mostly families of color in urban areas. In North Carolina, charter schools tend to be whiter than the statewide average.

The demographics of charter schools have been shifting for several years to close to statewide averages. That’s in part because more of them are using weighted lotteries to admit students. Those lotteries give applicants more weight — and a greater likelihood fo getting into the school — if the applicant is “educationally disadvantaged.” Charter schools create their own rules for weighted lotteries but must include more weight for low-income students.

But most schools don’t have weighted lotteries and charter schools are still more concentrated in urban areas, said Kris Nordstrom, a senior policy analyst with the Education & Law Project at the left-learning North Carolina Justice Center, which has been critical of charter schools. From what Nordstrom has researched, the demographic disparities between urban charter schools and the counties they are located in are more stark than when simply comparing statewide averages.

The impact on segregation of the expansion of private school vouchers will be hard to measure, Ayscue said. Individual private schools don’t report their demographic data publicly. Demographic data are available on voucher recipients only on a statewide basis.

North Carolina

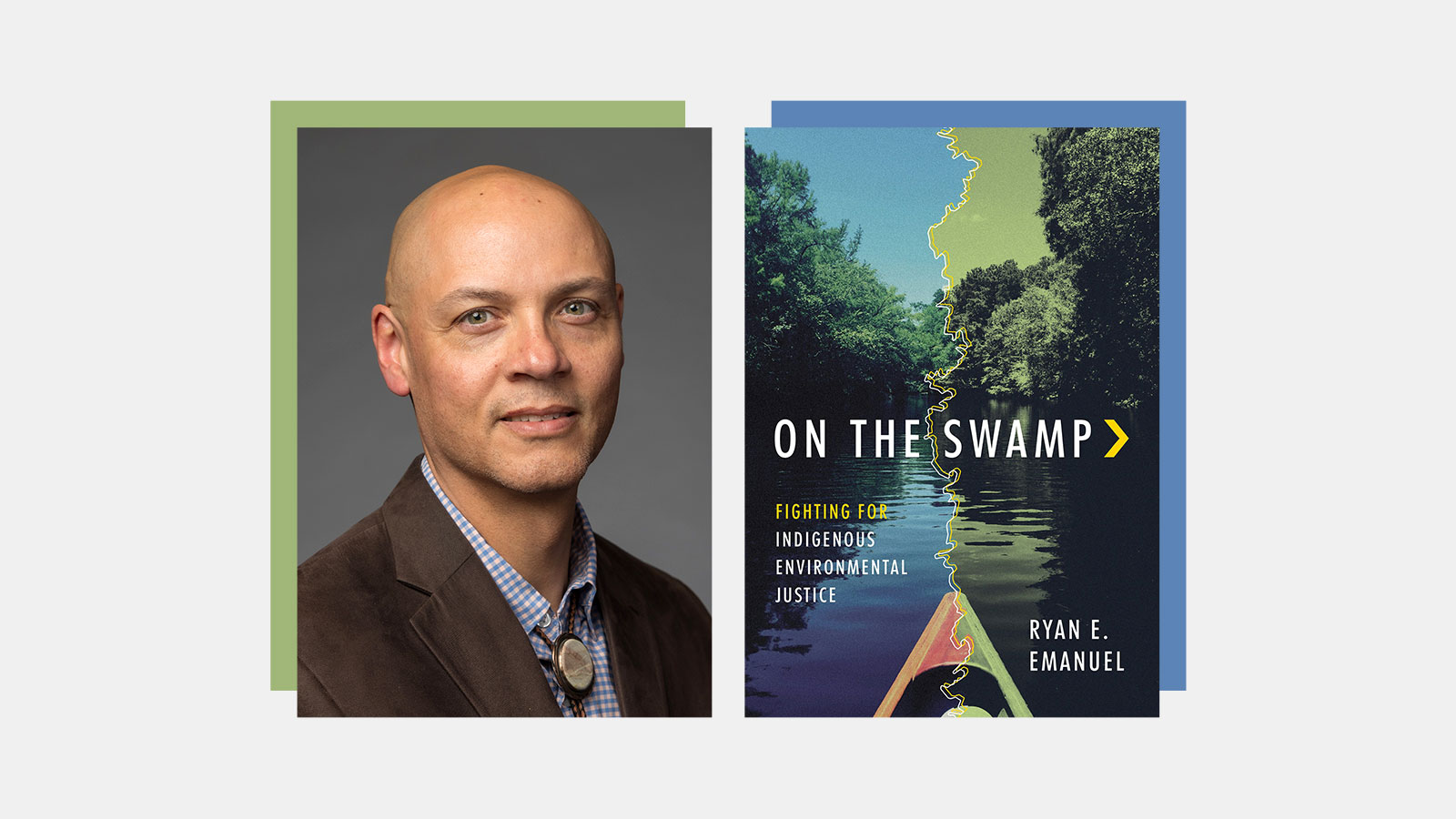

In a debut book, a love letter to eastern North Carolina — and an indictment of colonialism as a driver of climate change

This story was produced in partnership with Covering Climate Now.

As the planet grapples with the ever-starker consequences of climate change, a debut book by Lumbee citizen and Duke University scientist Ryan Emanuel makes a convincing argument that climate change isn’t the problem — it’s a symptom. The problem, Emanuel explains in On the Swamp: Fighting for Indigenous Environmental Justice, is settler colonialism and its extractive mindset, which for centuries have threatened and reshaped landscapes including Emanuel’s ancestral homeland in what today is eastern North Carolina. Real environmental solutions, Emanuel writes, require consulting with the Indigenous peoples who have both millennia of experience caring for specific places, and the foresight to avoid long-term disasters that can result from short-term material gain.

Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1977, Emanuel was one of a handful of Native students at school. He spent summers visiting family in Robeson County, North Carolina, the cultural center of the Lumbee Tribe, or People of the Dark Water, where he played outside with other children, occasionally exploring a nearby swamp, one of the many lush waterways that slowly wind through the region, with a cousin. Today, Emanuel visits those swamps to conduct research. He describes them with an abiding, sometimes poetic affection, such as one spring day when he stands calf-deep in swamp water, admiring white dogwood flowers floating on the dark surface as tadpoles dart underneath.

But that affection lives with tension. Emanuel describes trying to collect “reeking” floodwater samples from a ditch after 2018’s Hurricane Florence. In Emanuel’s retelling, a nearby landowner — a white farmer who uses poultry waste as fertilizer — threatens to shoot Emanuel. The sampling, the man believes, would threaten his livelihood, which is wrapped up in North Carolina’s extractive animal farming industry — a system of giant, polluting “concentrated animal feed operations” overwhelmingly owned and operated by white people, and exposing mainly racial minorities to dirty air and water. They are a sharp contrast to the small backyard farms and truck crops grown by Emanuel’s aunties and uncles back in Robeson County a generation ago. As the man holds his gun and lectures about environmental monitoring, Emanuel reflects silently that they are standing on his ancestors’ land. Ever the researcher, he later finds deed books from around the Revolutionary War showing Emanuels once owned more than a hundred acres of land in the vicinity. Still, he holds a wry sympathy for the man, who, he notes, is worried that environmental data will jeopardize his way of life in a place his family has lived for generations.

Eastern North Carolina is a landscape of sandy fields interwoven with lush riverways and swamplands, shaded by knobby-kneed bald cypress trees and soaked with gently-moving waterways the deep brown of “richly steeped tea,” Emanuel writes. In addition to water, the region oozes history: It includes Warren County, known as the birthplace of the environmental justice movement, where local and national civil rights leaders, protesting North Carolina’s decision to dump toxic, PCB-laden soil in a new landfill in a predominantly-Black community, coined the term “environmental racism.” It’s also the mythological birthplace of English colonialism, Roanoke Island. On the Swamp draws a through line from early colonization of the continent to ongoing fights against environmental racism and for climate justice, with detailed stops along the way: Emanuel’s meticulous research illustrates how the white supremacism that settlers used to justify colonialism still harms marginalized communities — both directly, through polluting industries, and indirectly, through climate change — today.

With convoluted waterways accessible only by small boats, and hidden hillocks of high ground where people could camp and grow crops, the swamplands of eastern North Carolina protected Emanuel’s ancestors, along with many other Indigenous peoples, from genocide and enslavement by settlers. Today, with climate change alternately drying out swamplands or flooding them with polluted water from swine and poultry operations, it’s the swamps that need protection, both as a geographic place, and an idea of home. The Lumbee nation is the largest Indigenous nation in the eastern United States, but because the Lumbee Tribe gained only limited federal recognition during the 1950s Termination Era, its sovereignty is still challenged by the federal government and other Indigenous nations. Today, federal and state governments have no legal obligation to consult with the Lumbee Tribe when permitting industry or development, although the federal government does with Indigenous nations that have full federal recognition, and many industrial projects get built in Robeson County.

In writing that’s both affectionate and candid, On the Swamp is a warning about, and a celebration of, eastern North Carolina. Though the region seems besieged by environmental threats, Indigenous nations including the Lumbee are fighting for anticolonial climate justice.

Grist recently spoke with Emanuel about On the Swamp.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q. What motivated you to write this book?

A. Many years ago, I thought that I wanted to write a feel-good book about celebrating the Lumbee River and the Lumbee Tribe’s connection with it, and talking about all the reasons why it’s beautiful, and amazing, and important to us. So I thought that I would write this essentially nature story, right? But as my work evolved, and as I started thinking more critically about what I actually should be writing, I realized that I couldn’t tell that love story about the river without talking about difficult issues around pollution, climate change, and sustainability, and broader themes of environmental justice and Indigenous rights.

Q. Could you tell me about your connection to place?

A. I have a relationship to Robeson County that’s complicated by the fact that my family lived in Charlotte, and I went to school in Charlotte, and we went to church in Charlotte. But two weekends every month, and every major holiday, we were in Robeson County. And so I’m an insider, but I’m also not an insider. I’ve got a different lens through which I look at Robeson County because of my urban upbringing, but it doesn’t diminish the love that I have for that place, and it doesn’t keep me from calling it my home. I’ve always called it home. Charlotte was the place where we stayed. And Robeson County was home.

I can’t see the Lumbee River without thinking about the fact that it is physically integrating all of these different landscapes that I care about, [and] a truly beautiful place.

Q. In 2020, after years of protests and legal battles, Dominion Energy and Duke Energy canceled the Atlantic Coast pipeline, which would have carried natural gas 600 miles from West Virginia to Robeson County. In On the Swamp, you note that a quarter of Native Americans in North Carolina lived along the proposed route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. What was the meaning of the Atlantic Coast pipeline project for Lumbee people?

A. That was an issue very few Lumbee people paid attention to, until they saw the broader context to the project and realized that such an outsized portion of the people who would be affected by the construction and operation of that pipeline were not only Native American, but were specifically Lumbee. I think that’s what generated a lot of outrage, because for better or for worse, we’re used to being treated like a sacrifice zone.

The Atlantic Coast pipeline gave us an easy way to zoom out and ask questions like, “OK, who is going to be affected by this project? Who’s making money off of this project?”

It was also a way to engage with larger questions about things like energy policy in the face of climate change and greenhouse gas emissions. [It] brought up philosophical questions of how we feel about the continued use of fossil fuels and the investment in brand new fossil fuel infrastructure that’s going to last 30, 40, or 50 years, at a time when everybody knows we shouldn’t be doing that.

Q. At the end of the day, the Atlantic Coast pipeline didn’t happen. What do you think is the main reason?

A. The collective resistance of all of these organizations — tribal nations, committed individuals, grassroots organizations — was enough to stall this project, until the developers realized that they had fallen into the Concorde fallacy. Basically, they got to the point where they realized that spending more money was not going to get them out of the hole they had dug in terms of opposition to this project.

But as long as [developers] hold on to those [property] easements, there’s certainly a threat of future development.

Q. You write that people can physically stay on their ancestral land and still have the place taken away by climate change, or by development projects. Can you talk a little bit about still having the land but somehow losing the place?

A. The place is not a set of geographic coordinates. It’s an integration of all the natural and built aspects of the environment. And so climate change, deforestation, these other types of industrialized activities, they have the potential to sweep that place out from under you, like having the rug pulled out. All of the things that make a set of geographic coordinates a beloved place can become unraveled, by these unsustainable processes of climate change and unsustainable development. I think that the case studies in [On the Swamp] show some of the specific ways that that can happen.

Q. Could you talk about your experiences as a researcher going out in the field, navigating modern land ownership systems, and how that connects to climate change?

A. I don’t know if it’s fair to say that I have to bite my tongue a lot, but I kind of feel that way. When I hear people talk about their ownership of our ancestral lands — I’m a mix of an optimist and a realist, and I understand that we’re not going to turn back the clock. And frankly, I’m not sure I want to, because Lumbee people are ourselves a product of colonial conflict, and we wouldn’t exist as the distinct nation that we are today, if it were not for the colonial violence that we survived. We might exist as our ancestral nations and communities, but we definitely wouldn’t be Lumbee people. So this is a complicated issue for me.

When we think about the front lines of climate change, we don’t often think about Robeson County, North Carolina. But because our community is so attuned to that specific place, we’re not going to pick up and move if the summers get too hot, or if the droughts are too severe. That’s not an option for us. So I think that some of the urgency that I feel is not too different from the urgency that you hear from other [Indigenous] people who are similarly situated on the front lines of climate change.

Q. Something else that you make a really strong point about in this book is that something can be a “solution” to climate change, but not sustainable, such as energy companies trying to capture methane at giant hog farms in Robeson County. How should people think about climate solutions, in order to also take into account their negatives?

A. The reason why people latch onto this swine biogas capture scheme is if you simply run the numbers, based on the methane and the carbon dioxide budgets, it looks pretty good.

But a swine facility is a lot more than just a source of methane to the atmosphere, right? It’s all these other things in terms of water pollution, and aerosols, and even things like labor issues and animal rights. There are all these other things that are attached to that kind of facility. If you make a decision that means that facility will persist for decades into the future operating basically as-is, that has serious implications for specific people who live nearby, and for society more broadly. We don’t tend to think through all those contingencies when we make decisions about greenhouse gas budgets.

Q. What are some ways that the Lumbee tribe is proactively trying to adapt to climate change?

A. Climate change is not an explicit motivation [for the Lumbee Tribe]. If you go and read on the Lumbee Tribe’s housing programs website, I don’t think you’re going to find any rationale that says, “We’re [building housing] to address climate change.” But they are.

Getting people into higher-quality, well-insulated and energy-efficient houses is a big deal when it comes to addressing climate change, because we have a lot of people who live in mobile homes, and those are some of the most poorly insulated and least efficient places that you could be. And maybe 40 years ago, when our extreme summer heat wasn’t so bad, that wasn’t such a huge deal. But it’s a huge deal now.

Q. What is the connection between colonialism and climate change for eastern North Carolina, and why is drawing that line necessary?

A. The one sentence answer is, “You reap what you sow.”

The longer answer is, the beginning of making things right is telling the truth about how things became wrong in the first place. And so I really want this book to start conversations on solving these issues. We really can’t solve them in meaningful ways unless we not only acknowledge, but also fully understand, how we got to this point.

North Carolina

North Carolina Legislators Want To Ban Masks, Even For Health Reasons

Simone Hetherington, a speaker during public comment, urges lawmakers not to pass the masking bill … [+]

The North Carolina State Senate has voted along party lines this week to ban wearing masks in public.

Seventy years ago some states passed anti-mask laws as a response to the Ku Klux Klan, whose members often hid their identities dressed in robes and hoods.

The North Carolina bill repeals an exception to the old anti-mask laws that was enacted during the early phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, which allows people to wear masks in public for “health and safety reasons.”

According to The Hill, Republican supporters of the ban said it would help law enforcement “crack down on pro-Palestine protesters who wear masks.” They accuse demonstrators of “abusing Covid-19 pandemic-era practices to hide their identities.”

To reinforce the deterrent, the proposed law states that if a person is arrested for protesting while masked, authorities would elevate the classification of the misdemeanor or felony by one level.

Democrats in North Carolina have raised concerns about the bill, particularly for the immunocompromised or those who may want to continue to wear masks during cancer treatments. And others have also chimed in, including Jerome Adams, former Surgeon General in the Trump Administration, who posted on Twitter that “it’s disturbing to think immunocompromised and cancer patients could be deemed criminals for following medical advice aimed at safeguarding their health.”

Additionally, there are folks who may have legitimate health reasons for wearing medical masks, including asthma sufferers, people exposed to wildfire and smoke or individuals who want to protect themselves, their families and others from pathogens like Covid-19 and influenza.

Indeed, for decades people across Asia have worn masks for a variety of reasons, as USA Today explained at the outset of the coronavirus epidemic. Japanese often wear masks when sick to curb transmission. Philippine motorcycle riders will put on face coverings to protect from exhaust fumes in heavy traffic. Similarly, citizens of Taiwan use masks to protect themselves from air pollution and airborne germs.

There are exemptions incorporated into the proposed ban, including for Halloween or specific types of work that require face coverings. There’s even an exception that specifically allows members of a “secret society or organization to wear masks or hoods in a parade or demonstration if they obtain a permit,” as WRAL in Raleigh, North Carolina reports.

Upon reading this, a Democratic State Senator in North Carolina, Sydney Batch, asked, “so this bill will protect the Ku Klux Klan to wear masks in public, but someone who’s immunocompromised like myself cannot wear a mask?”

It’s noteworthy that if a group like the KKK were to file for and obtain a permit to demonstrate, under the proposed law they could wear face coverings. And this isn’t a theoretical point. The KKK has a history of organizing rallies in North Carolina, like one they held in 2019. The question is, could pro-Palestinian demonstrators get a similar permit now and be allowed to wear masks or other face coverings? Presumably not.

The American Civil Liberties Union argues that the law is specifically being used to target those who wear face coverings while protesting the war in Gaza, which in the ACLU’s view amounts to “selective prosecution of a disfavored movement.”

There are other legal aspects that could also be invoked that pertain to the constitutionality of such a ban.

Remember when at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic wearing a mask was mandatory in public places in many jurisdictions as well as federal buildings and property and this provoked an outcry from people on the grounds of freedom of choice? Judges overturned certain mask mandates at both the federal and state levels and did so on constitutional grounds. By the same token, though in a kind of role reversal, it could now be argued that by banning masks people won’t be able to exercise their freedom of choice to protect themselves. It stands to reason that a constitutional law debate could ensue if the North Carolina ban goes into effect.

In the meantime, the bill now moves to the House for the next vote. From there it may head to Governor Roy Cooper’s desk. He’s a Democrat and will likely veto the legislation. But the North Carolina Republican Party has a supermajority and can override a possible veto.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRFK Jr said a worm ate part of his brain and died in his head

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPentagon chief confirms US pause on weapons shipment to Israel

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoStudents and civil rights groups blast police response to campus protests

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoConvicted MEP's expense claims must be published: EU court

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCalifornia Gov Gavin Newsom roasted over video promoting state's ‘record’ tourism: ‘Smoke and mirrors’

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOhio AG defends letter warning 'woke' masked anti-Israel protesters they face prison time: 'We have a society'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoBiden’s decision to pull Israel weapons shipment kept quiet until after Holocaust remembrance address: report

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoNine Things We Learned From TikTok’s Lawsuit Against The US Government