Dallas, TX

Renowned Dallas journalist and bestselling author Hugh Aynesworth has died

Hugh Grant Aynesworth was, as the title of his first book declared, “a witness to history.”

For such an amiable — even soft-spoken — man, Aynesworth had a resumé of news stories and investigations that reads like a chronicle of the past 60 years of American violence and trauma. He personally saw and covered the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the arrest and shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald. In 1993, he covered the Branch Davidian siege at Waco. He reported on the 1995 bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City which killed 168 people.

Over the course of a year, he and a partner interviewed serial killer Ted Bundy in a Florida prison in 1980 while Bundy’s murder convictions were still being appealed.

On November 12 this year, after Aynesworth was admitted to the UT Southwestern emergency room, doctors determined he had suffered a stroke months before. After a week at the hospital and a week in rehab, he returned home on November 25.

Earlier this month, his wife, Paula Aynesworth, decided he needed to enter hospice care.

He died Saturday at home. Aynesworth was 92.

Remembering a storied career

In 2007, Aynesworth summed up his years as a journalist at the 15th Annual Harrison County Student Achievement Banquet in his hometown of Clarksburg, West Virginia.

“I’ve been offered bribes and threatened and maligned and witnessed some of the most horrifying events of our lifetime.”

Aynesworth added, “It’s been a strange life. It’s been so much fun, and I’ve been so very fortunate.”

“Personally, I don’t know that there’s ever been a better reporter to come out of Dallas, really,” said Robert Mong, president of the University of North Texas at Dallas and former editor-in-chief at The Dallas Morning News.

“What strikes me about Hugh was that he could walk the halls of power easily enough, get people to confide in him,” said Jim Schutze, former longtime city columnist for the Times Herald.

Schutze came to Dallas in 1978. He said he’d heard, even before he arrived, that Aynesworth was a reporting legend.

“He had some years on the police beat under his belt, and he could also go talk to a bunch of striking coal miners around a barrel fire. He had a full, 360-degree compass,” Schutze added.

In addition to interviewing Ted Bundy, Aynesworth played a major role in debunking another infamous serial killer. In 1986, he and fellow Dallas Times Herald reporter Jim Henderson exposed convicted serial killer Henry Lee Lucas as a fraud. Lucas, a drifter in jail for two killings, had convinced Texas Rangers — and other law enforcement officials across the country eager to close long-cold cases — that he had improbably managed to murder more than 100 women.

On tape with Aynesworth, Lucas said the total number of victims, male and female, was “360, minimum.” That later became 600.

Aynesworth and Henderson proved this was physically impossible: Lucas would have had to drive his Ford station wagon 11,000 miles in a single month, while managing to stop repeatedly along the way to kill the occasional victim. On the date of one murder in Houston, Aynesworth and Henderson proved Lucas was in jail in Maryland at the time.

It’s now believed that, at most, Lucas killed three people. He was a fabulist who just liked the attention and the milkshakes that came with telling police what they wanted to hear.

Later that year, Aynesworth and Henderson were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting.

“I have always felt that they should have won the Pulitzer Prize for revealing the hoax of Henry Lee Lucas,” said Mong.

In total, Aynesworth was a Pulitzer finalist four times.

Schutze also recalled that, in his early days at the Times Herald, he began hearing tales about how Aynesworth was so good at his job because he was getting scoops handed to him. He was on the FBI payroll.

Schutze took his concerns to an editor.

“He said, ‘Hugh doesn’t work for the FBI. The FBI works for Hugh.’ He said, ‘Hugh could sit down with these guys, and they thought, after one drink, he was an FBI agent.’”

Schutze said that whatever else he was — book author, editor, Newsweek bureau chief — “Hugh was just a very, very, very good reporter.”

Hugh Aynesworth on Kennedy conspiracy theories

Aynesworth was a throwback as a journalist — not just to the days before 24-hour cable news and the internet, but to when college journalism programs were rare and no one had heard of media studies. In the late 1940s when Aynesworth started working, reporters typically got their on-the-job training at a local paper covering city hall or the police beat.

Which is precisely how Aynesworth began. Raised by his mother, who had to take in laundry to make ends meet, he graduated high school in Nutter Fort, West Virginia, and attended that state’s Salem College — for one semester. He dropped out and in 1948 started as a freelancer for the Clarksburg Exponent-Telegram (current print circulation: 17,000).

Although he became known for his true crime reporting, over the course of his 70-year career, Aynesworth was much more: a daily news reporter, a 23-year-old managing editor, a business writer, a sports editor, an investigator for the ABC News program 20/20, and the author of two books — November 22, 1963: Witness to History and JFK: Breaking the News. He also co-authored seven more with Stephen Michaud, including The Vengeful Heart and Other Stories and Ted Bundy: Conversations with a Killer.

Aynesworth’s most recent project in 2019 was a four-part Netflix documentary on Ted Bundy. He served as a producer on the series — his third effort as a TV producer.

Conversations with a killer

Interviewing Bundy in 1980 while the serial killer awaited his appeals on the Florida death row was Aynesworth’s first collaboration with Michaud, his writing partner. Michaud said the ‘charismatic killer’ had sought out journalists to tell his story because the cases against him were entirely inferential and circumstantial. This was before the widespread use of DNA testing, and there was no forensic evidence directly tying him to the murders. Bundy had been called “the killer with no fingerprints.”

In addition, Bundy “was contemptuous of the press,” Michaud said. He had a degree in psychology and was convinced he was smart enough to use the two reporters to find exculpatory evidence to save him from the death penalty.

In their interviews, Bundy simply would not admit to the killings or to anything about them. Frustrated, Michaud and Aynesworth changed tactics. They asked him to speculate about the ‘real murderer’ — what might have motivated him, how could he be so successful.

It worked. Eagerly, Bundy started to divulge details of the killings: his methods, his upbringing and his own psyche.

Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes

Michaud said he learned to flatter Bundy, play to his narcissism. Bundy may have been smart, but “Ted was emotionally about 12.”

“Then Aynesworth went in and said, ‘Well, I didn’t buy any of that. I want to talk to you about it.’”

He bluntly asked Bundy to go through it all again, explain it to him: Why would any rational person do some of the grisly things this killer had done to his victims?

“It was classic ‘good cop, bad cop,’” Michaud said.

The two had Bundy talking for more than 100 hours over the course of a year. While Michaud continued editing the results, Aynesworth checked out the leads. They uncovered nothing to contradict Bundy’s guilt.

Their book, Conversations with a Killer, was a New York Times bestseller.

In 2019, Aynesworth discussed his dealings with Bundy in a public interview for the The Dallas Morning News.

“We did not get along,” Aynesworth recalled. “He was killing young girls. And at that time, I had two beautiful young daughters.”

Michaud said that, as a self-taught interviewer, “Hugh had infinite patience. He would listen and listen. He’d be waiting until whatever tension there might have been dropped away, and they were just chatting. And then he’d say, ‘Well, what about this?’ And the guy or woman would say, ‘Oh [expletive], this guy knows more than I thought he did!’ And then Hugh would go back through it again and again.”

“I don’t want to use the expression ‘good old boy charm,’” Michaud said. “But that’s what he had.”

“Then the other part was that Hugh was an absolute natural snoop. There was nothing that he didn’t want to get his nose into. He taught me how to read upside down. He constantly picked up stuff. It was this kind of immediately making himself at home and making the other person at home. I had done a lot of interviewing, but I’d never seen anything like it.”

Tom C. Dillard

/

The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

Covering the Kennedy assassination

In 1963, Aynesworth left a job with United Press International in Denver to become the aerospace reporter for The Dallas Morning News. On November 22 of that year, the 32-year-old Aynesworth walked over from the newspaper’s offices to Dealey Plaza to witness the passing motorcade of President John F. Kennedy.

“I was proud, really, that they were giving him such a welcome,” Aynesworth recalled later for the KERA TV documentary JFK: Breaking the News. He was pleased at the city’s enthusiastic reception for the liberal, Democratic president whom several prominent Dallasites — including the owner of The Dallas Morning News — had publicly opposed and mocked.

“You know,” he heard one person in the crowd say, “With all the ruckus, with all this hatred in the city, I’m amazed he came. I’m amazed he had the guts.”

Then, as Aynesworth reached Elm Street, he heard what sounded like a motorcycle backfiring. Then two more — now, clearly, the sound of gunshots.

“I almost tear up sometimes when I think about what happened, and the feeling and the gut wrenching, not knowing what to do,” he said in JFK: Breaking the News. “But it was so stark and so brutal. A beautiful day just turned into chaos.”

Aynesworth had no paper or pen with him but knew he had to start interviewing eyewitnesses. Using a pencil he bought from a young boy, he started writing his notes on an electric bill and a gas bill he had in his pocket

In addition to his original, on-the-scene interviews, Aynesworth was the first to interview Marina Oswald, the alleged assassin’s widow. He was also the first to break the news of Oswald’s suicide attempt, as well as his escape route from Dealey Plaza — facts the FBI had not released.

The assassination and its aftermath shaped much of his subsequent career. Throughout the ’60s and early ’70s, Aynesworth became so immersed in tracking down even the most outlandish claims, that the late Nora Ephron profiled Aynesworth and Times Herald reporter Robert Dudney in a 1976 Esquire feature, The Assassination Reporters. It was later collected in her book, Scribble, Scribble.

One of Aynesworth’s biggest scoops about the assassination was the publication of diaries Oswald had written while in Russia — and which the Warren Commission had not released. But, for the most part, the two reporters regularly answered four assassination-related calls a day from people, most of whom Aynesworth called “flakes.”

“I’ve heard five or six people confess that they were part of a conspiracy to kill Kennedy,” Aynesworth told Ephron. “Only it turns out that they were in jail, or in a loony bin in Atlanta, at the time. There were about 500 people in Dealey Plaza that day. In twenty years, there’ll be ten thousand.”

Ephron noted the topsy-turvy nature of Aynesworth’s work. No one wanted to uncover an assassination conspiracy and disprove the Warren Report more than he did. Investigative reporters typically work hard to bring such plots to light: “Aynesworth spent much of his time knocking them down.”

By the time of the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s death, he’d long since become a go-to eyewitness, a frequent public authority on the topic and an outspoken debunker of the many alternative theories of the JFK assassination.

“So many people just want to be somebody,” he said in Breaking the News. “Sort of like Oswald and Ruby. They wanted to be somebody. That’s the same way with a lot of eyewitnesses.”

His most public effort at debunking came with the early conspiracy plots promulgated by New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison. Garrison’s version of events became enshrined in the 1991 Oliver Stone film, JFK.

Garrison originally asked Aynesworth for help. Although, by that time, the journalist had moved to Houston, hoping to put the assassination behind him. But he soon saw in his investigations that Garrison had developed an elaborate and variable version of events. As soon as Aynesworth knocked down one source, one suspect, one theory, Garrison had another.

By 1967, Aynesworth wrote in Newsweek: “Jim Garrison is right. There has been a conspiracy in New Orleans — but it is a plot of Garrison’s own making.”

In the end, after decades of intense scrutiny by forensic experts, journalists, federal investigators and assassination buffs, much of Aynesworth’s basic narrative timeline and his reporting on the Kennedy assassination have held up.

Aynesworth joined the Press Club of Dallas in the early ’60s. He served as its president in 2007. In 2017, the group named its award for excellence in journalism after Aynesworth.

Hugh Aynesworth has been married to Paula Aynesworth, née Paula Kathleen Butler, since 1987. She worked for KERA for 34 years as a sales executive. Aynesworth was previously married to Paula Ruth Eby (1962-1977) and Leslee Marie May (1980-1983). He and Paula Eby had two daughters, Allyson and Allyssa, and a son, Grant, who died in 2016. Aynesworth has four grandchildren.

Plans for a memorial service have not been announced.

Dallas, TX

Stars HC In Hot Water Following Playoff Exit

The Dallas Stars looked poised for a chance at the Stanley Cup as they head into the Western Conference Final against the Edmonton Oilers. Despite being the favorites, the Stars sealed just one win as the Oilers won the series in five games to advance to the Stanley Cup Final.

Not only did the Stars fall apart in the series, but head coach Peter also DeBoer may have put himself in hot water with the rest of the organization. DeBoer pulled star goalie Jake Oettinger early and in embarrassing fashion in the deciding Game 5, a move that likely put a damper on morale.

Following the game, DeBoer defended his move by saying Oettinger had a track record of struggling against the Oilers. DeBoer later referenced a conversation he and the coaching staff had about possibly not starting Oettinger in Game 4 thanks to an illness.

Between the awkward pulling in Game 5 and standing his ground on his decision, Stars players are not happy with DeBoer. According to David Pagnotta of the Fourth Period, players voiced their concerns during exit interviews.

“Noise out of Dallas re: Pete DeBoer,” Pagnotta said in a tweet. “Per multiple sources, players are not pleased with how he handled several situations during the WCF, along with post Gm5 & exit media remarks. Told players voiced concerns during internal exit interviews.”

Pagnotta also mentioned that DeBoer only has one year left on his contract. With just one year left, the chances of a head coach firing are much more likely. If not a firing, talks of a contract extension are almost surely not happening.

Head coaching searches have been taking place with numerous teams across the league. The Stars would be very late to the part if they decided to part ways with DeBoer right now, with most of the big names already being scooped up.

The Stars have a good team, three straight trips to the Western Conference Final is nothing to scoff at, but they need more. The players know their roles but don’t seem to be speaking highly of their bench boss.

Make sure you bookmark Breakaway On SI for the latest news, exclusive interviews, recruiting coverage, and more!

Dallas, TX

Cowboys ‘Swiss Army knife’ could play vital role for offense in 2025

The Dallas Cowboys offense will be looking to make a statement this upcoming season, after injuries stole what could have been a potential great season in 2024.

The front office has made some moves in the offseason and in the 2025 NFL Draft that should give the unit a lot of confidence heading into a new year, including the biggest move of adding wide receiver George Pickens after a trade with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

However, what role can returning players expect in the offense during the upcoming NFL campaign?

MORE: Future HOFer rips Cowboys for ‘ one of worst offseasons of all-time’

Tommy Yarrish of the Dallas Cowboys’ official website feels that running back Hunter Luepke could play a pivotal role in 2025.

“The Swiss army knife that is Hunter Luepke can serve in a lot of different roles for the Cowboys’ offense, and that’s been on display early in OTAs and his overall time in Dallas. He’s played running back, fullback and tight end along with special teams,” he wrote. “So, which spot does he settle into the best? Is it all of the above, or does Brian Schottenheimer find a permanent home and role for him in his offense?

“The good news for Luepke and the Cowboys is he can do a lot, and with an emphasis on wanting to run the football his ability as a blocker or short down back gives him a versatile skill set that can be used in-line as a tight end or as a fullback.”

MORE: Cowboys’ 3 most important needs entering 2025 training camp

Luepke could become a do it all player for the franchise, that could be the Achilles heel for any defense the Cowboys face.

— Enjoy free coverage of the Cowboys from Dallas Cowboys on SI —

Dallas Cowboys’ salary cap space ahead of post-June 1 releases

NFL insider thinks Jerry Jones is delaying Micah Parsons’ contract for media attention

Cowboys ‘biggest strength’ for 2025 season is bad news for NFL QBs

Cowboys’ CeeDee Lamb ranks among NFL elite in historic receiving stat

PHOTOS: Meet Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader Sophy Laufer

Dallas, TX

Dallas weather: June 1 overnight forecast

Severe Thunderstorm Watch

until MON 12:00 AM CDT, Bosque County, Dallas County, Navarro County, Somervell County, Erath County, Parker County, Hood County, Freestone County, Tarrant County, Palo Pinto County, Ellis County, Johnson County, Hill County

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMOVIE REVIEW – Mission: Impossible 8 has Tom Cruise facing his final reckoning

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘Magellan’ Review: Gael Garcia Bernal Plays the Famous Explorer in Lav Diaz’s Exquisitely Shot Challenge of an Arthouse Epic

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoMaryland, Cornell to face off in NCAA men’s lacrosse championship game

-

Tennessee1 week ago

Tennessee1 week agoTennessee ace Karlyn Pickens breaks her own record for fastest softball pitch ever thrown

-

Utah1 week ago

Utah1 week agoUtah Republicans ignore study supporting gender-affirming care for trans youth. It's research they demanded

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoHarvard has $52,000,000: Trump mounts attack, backs foreign student enrolment ban

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump admin asking federal agencies to cancel remaining Harvard contracts

-

South-Carolina1 week ago

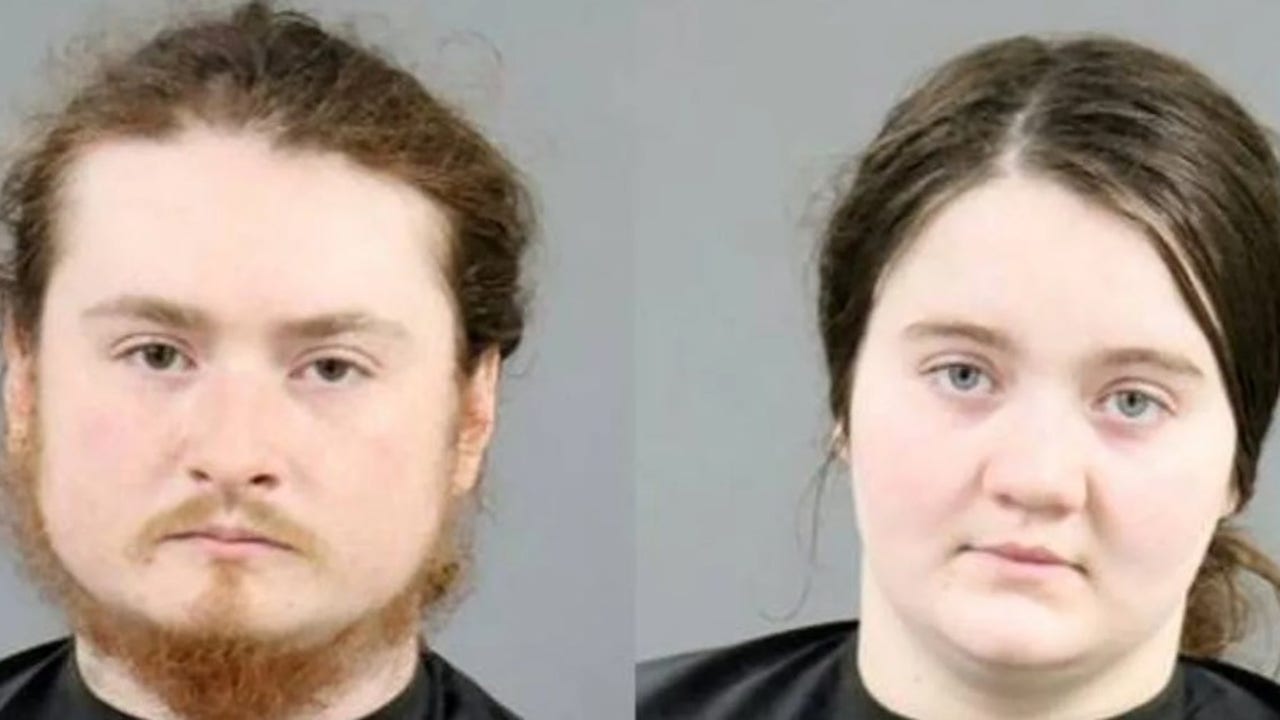

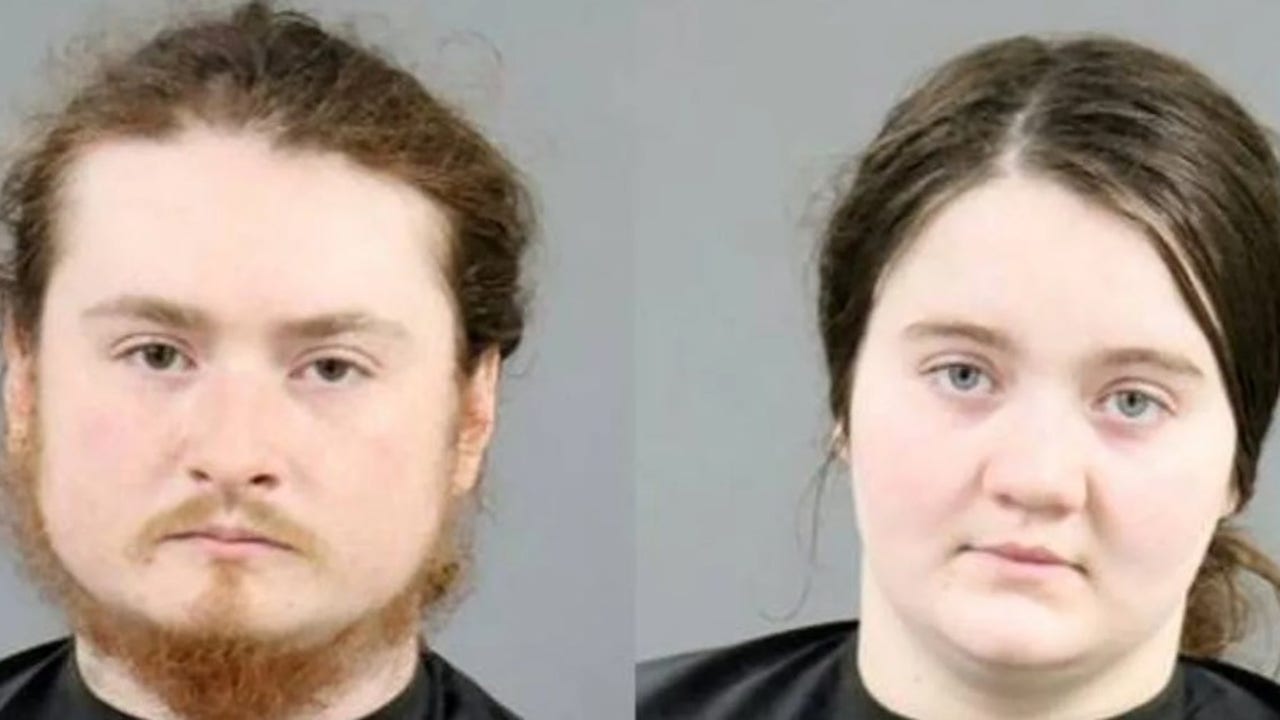

South-Carolina1 week agoSouth Carolina infant rescued from filthy home infested with animals, some dead