Science

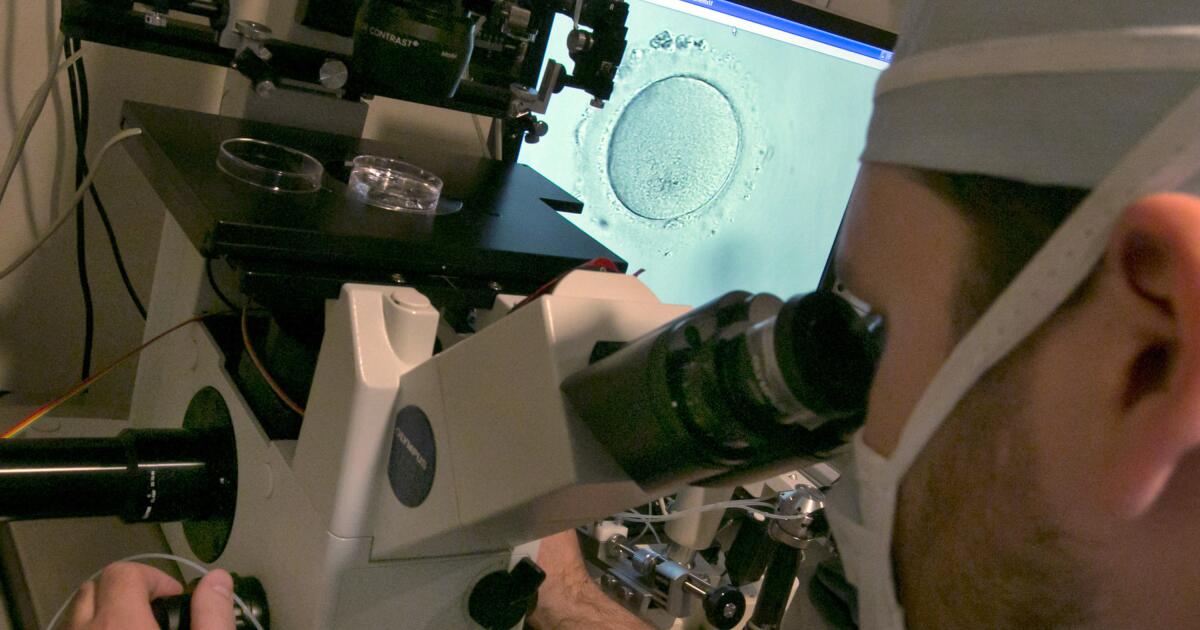

'What is this, “The Handmaid’s Tale”?' Exploring moral questions posed by controversial IVF ruling

Is a frozen embryo a child?

The Alabama Supreme Court says yes. In ruling this month that three couples who lost frozen embryos in a storage facility accident could sue for wrongful death of a minor child, the court wrote that the “natural, ordinary, commonly understood meaning” of the word “child” includes an “unborn child” — whether that’s a fetus in a womb or an embryo in a freezer.

Hospitals and clinics across the conservative state have since paused in vitro fertilization services as they scramble to figure out the legal and ethical ramifications of the decision. Transport companies are also on hold as they assess the risks of carrying embryos out of state.

To better understand the ethics of IVF and what this ruling means for clinics, families and the more than a million embryos stored in freezers across the country, we spoke with Vardit Ravitsky, a professor of bioethics at the University of Montreal and president of the Hastings Center, an independent bioethics research institute in New York. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You became interested in the ethical issues of IVF as a college student, when a friend asked if you would consider donating an egg.

I was almost 20. I was absolutely fascinated by the notion of carrying a fetus that is not genetically related to you. What does that mean to be the biological mother of a fetus that is genetically not your child? On the flip side, what happens when you give your egg to another woman and you have a genetically related child that is not yours?

The notion of genetic relatedness — IVF kind of broke that. You can now carry a fetus that is not yours; you can give your genetics to another person. That blew my mind, because it took the notion of motherhood that was the same for all of human history and broke it down into two components.

So technology can change our fundamental concept of human beings. And that’s what’s happening here. We’re talking about a batch of cells on ice, and we call it a child. That just wasn’t possible before.

Do people have a common understanding of what an embryo is?

Embryo, fetus and newborn baby are, first and foremost, medical biological terms. An embryo is the name we use in the beginning of the development, up to about 11 weeks pregnancy or nine weeks in embryonic development. Then, when it’s more developed, we call it a fetus. When it breathes on its own, outside of a female body, we call it a baby.

The separate issue is when do we accord these entities moral status? We can call them whatever we want; we can call them cells or we can call them children. That’s a value-based, societal decision.

Do we treat embryos outside of the body morally in the same way that we treat them inside of the body? In most jurisdictions, we treat them differently.

For years, anti-abortion advocates in red states have pushed “fetal personhood” — the idea that life begins at conception and fetuses are children entitled to legal rights. Now Alabama’s Supreme Court has ruled that frozen embryos should be considered children. What ethical questions does this pose?

To imply or say explicitly that [frozen embryos] are children, in the same sense that fetuses are seen as children, to me, that’s a very dangerous development.

Think about it logically: If you have a pregnancy and you do nothing, and there’s no miscarriage, a baby will be born. If you have an embryo in a dish in a freezer and you do nothing, there will not be a baby.

I would like women to have access to abortion because I care about their health and autonomy and their freedom to choose. When it comes to frozen embryos, it has nothing to do with a woman and with her body.

The potential of these embryos to become babies or children depends on so many steps: They have to be thawed, they have to continue to develop, they have to be implanted in the uterus, the uterus has to accept them, pregnancy has to develop. These are all steps that can still go wrong. To think of them as children in the same way that we think about newborns or fetuses is just, to me, going so far in how we understand the concept of a child.

In a concurring opinion, Alabama Chief Justice Tom Parker wrote that the people of the state adopted the “theologically based view” that “human life cannot be wrongfully destroyed without incurring the wrath of a holy God, who views the destruction of His image as an affront to Himself.” What does this mean for the future of IVF in conservative states?

Even if you say life begins at conception — for religious reasons or for any other values that you hold — you could still assign different moral values to the two scenarios of conception: outside of the body or inside of the body.

But if you take the view that life starts at conception and you apply that to in vitro, you are potentially shutting down IVF facility care. For clinics, as we’ve already seen beginning to happen, there are risks of handling human embryos that are very fragile biological entities. If the law treats them as children, then clinics rightly freak out about all that could happen to them during fertility treatments.

Unfortunately, accidents happen in clinics: freezers malfunction, embryos get destroyed by accident. Sometimes they have to be tested, and the testing harms them.

Does treating embryos as children necessarily call into question clinics’ ability to provide IVF?

Even if there’s technically the possibility of continuing to provide IVF, under this framework of “embryos are children” … if you’re actually convinced that you’re treating children under the microscope, the risks are so huge that I don’t see how clinics will continue to function long-term.

What ethical and legal dilemmas do clinics face?

What is the extent and the nature of their liability if something happens to an embryo? Is it criminal liability? What part of the law would they be liable for?

Now, in the current reality, couples can agree to the destruction of their embryos, they can donate them for research, they can allow genetic testing of those embryos. If this is a child that deserves independent protection, then what the couple wants becomes irrelevant.

If I owned a fertility clinic, I’d be very scared right now. If you treat embryos seriously as children, you cannot justify any level of risk. You cannot justify using them for training, for research. If we don’t allow genetic testing, we’re slowing down the quality of facility care, entire programs of research that are critical to biomedicine. The ripple effects are huge.

Could clinics be required to maintain all the frozen embryos they have in perpetuity?

Absolutely. If you don’t know what to do with them, other than implant in the uterus and start a pregnancy, then the obvious alternative under this ruling is to keep them frozen indefinitely, which costs hundreds of dollars a year. Currently, if parents abandon their embryos and stop paying the storage fee, clinics can destroy them after five years. But if that’s no longer an option, they will just accumulate and accumulate.

There are over a million frozen embryos in the U.S. today. And that number is growing all the time, because every time a woman undergoes a cycle, most often not all the embryos are used. So every cycle of IVF potentially leaves a few behind in a freezer. For clinics to carry that cost is a significant burden; IVF is already exceptionally expensive.

If a frozen embryo is viewed as a child, could it be interpreted as having a right to be implanted and born?

Absolutely yes. Celine Dion famously said that her frozen embryos in New York are children waiting to be born. You know Sofia Vergara from “Modern Family”? Her ex named their frozen embryos and sued in their name — they were the plaintiffs — that they have a right to be born. He argued he can make that happen because he has created a trust in their name, he has a surrogate, he will father them, he will take responsibility; they will want for nothing. He said leaving them on ice is like murdering them.

The court in Louisiana dismissed the case on a technicality that the embryos were created in California. They didn’t say, “You’re being ridiculous!” So that line of thinking — that frozen embryos have a right to be implanted in order to be born — has already been tried in the U.S., and it wasn’t even refuted fully.

What is this, “The Handmaid’s Tale”? Catch women and impregnate them because [embryos] have a right to be born? Where do we stop?

So what’s the fate of the more than a million embryos stored in freezers?

If state after state adopts this approach, then in those states, you will not be able to discard embryos or donate them for research or literally do anything with them, except seize them for reproduction. Will you be allowed to ship them to another state becomes the big question.

What does this ruling mean for patients in Alabama and other states with fetal personhood laws?

If I were in the middle of a cycle, and my eggs have not been retrieved yet, and I haven’t gone through fertilization, I’d be questioning whether I want to continue in Alabama. Because I wouldn’t know what I would be allowed to do with the embryos. If I had frozen embryos in Alabama, I would definitely look into shipping them to another state.

We have to remember that people going through IVF are very vulnerable. It’s a high-stress situation anyway, without the added layers of complexity and fear. At a medical level, such stress when you’re going through such an intricate process is definitely not in the best interest of patients.

As IVF clinics will shut down and move to other states, we’ll start seeing reproductive tourism within the U.S., just like we’re seeing with abortion. But the ethical problem with that is equity. Poor couples without resources will just not have access to IVF anymore.

It’s been more than 45 years since the world’s first baby conceived by IVF was born in the U.K. What was the significance of that technological development, and what were the key discussions when IVF was developed?

At the time, they were called test-tube babies. That’s a term that we’ve luckily abandoned, because it implied that they’re artificial children. Some people saw the actual methods of fertilizing the egg outside the body as violating the sacred nature of the creation of life. The Catholic Church was and still is against this, because of the method of conception.

The other concern was, “Oh, these children will be stigmatized. They will not be like other children.” Beyond medical risks that we didn’t know about at the time, how will they be viewed by society? Now it’s so normalized. In some countries, 1 in 6 children is born from assisted reproduction.

Do you think this is a real turning point?

If you think globally, Catholic countries have grappled with the status of embryos for years. Germany, for example, does not allow the destruction of embryos, because the embryos are defined as a person in the Constitution. And that’s for the historical reason that they reject any kind of selection associated to life and will do anything to protect the dignity of human life. So this is new to the U.S., but it’s not new in the world.

The shift has been from worrying about the technique, in itself, to worrying about who’s using it: gay couples using it, lesbian couples using it, single people using it with egg or sperm donation.

A married heterosexual couple using it to overcome infertility has become a nonissue. It became just medical care, no moral issues associated, other than: What do you do with your leftover frozen embryos that still remain?

Science

Pediatricians urge Americans to stick with previous vaccine schedule despite CDC’s changes

For decades, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spoke with a single voice when advising the nation’s families on when to vaccinate their children.

Since 1995, the two organizations worked together to publish a single vaccine schedule for parents and healthcare providers that clearly laid out which vaccines children should get and exactly when they should get them.

Today, that united front has fractured. This month, the Department of Health and Human Services announced drastic changes to the CDC’s vaccine schedule, slashing the number of diseases that it recommends U.S. children be routinely vaccinated against to 11 from 17. That follows the CDC’s decision last year to reverse its recommendation that all kids get the COVID-19 vaccine.

On Monday, the AAP released its own immunization guidelines, which now look very different from the federal government’s. The organization, which represents most of the nation’s primary care and specialty doctors for children, recommends that children continue to be routinely vaccinated against 18 diseases, just as the CDC did before Robert F. Kennedy Jr. took over the nation’s health agencies.

Endorsed by a dozen medical groups, the AAP schedule is far and away the preferred version for most healthcare practitioners. California’s public health department recommends that families and physicians follow the AAP schedule.

“As there is a lot of confusion going on with the constant new recommendations coming out of the federal government, it is important that we have a stable, trusted, evidence-based immunization schedule to follow and that’s the AAP schedule,” said Dr. Pia Pannaraj, a member of AAP’s infectious disease committee and professor of pediatrics at UC San Diego.

Both schedules recommend that all children be vaccinated against measles, mumps, rubella, polio, pertussis, tetanus, diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), pneumococcal disease, human papillomavirus (HPV) and varicella (better known as chickenpox).

AAP urges families to also routinely vaccinate their kids against hepatitis A and B, COVID-19, rotavirus, flu, meningococcal disease and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The CDC, on the other hand, now says these shots are optional for most kids, though it still recommends them for those in certain high-risk groups.

The schedules also vary in the recommended timing of certain shots. AAP advises that children get two doses of HPV vaccine starting at ages 9 to12, while the CDC recommends one dose at age 11 or 12. The AAP advocates starting the vaccine sooner, as younger immune systems produce more antibodies. While several recent studies found that a single dose of the vaccine confers as much protection as two, there is no single-dose HPV vaccine licensed in the U.S. yet.

The pediatricians’ group also continues to recommend the long-standing practice of a single shot combining the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) and varicella vaccines in order to limit the number of jabs children get. In September, a key CDC advisory panel stocked with hand-picked Kennedy appointees recommended that the MMR and varicella vaccines be given as separate shots, a move that confounded public health experts for its seeming lack of scientific basis.

The AAP is one of several medical groups suing HHS. The AAP’s suit describes as “arbitrary and capricious” Kennedy’s alterations to the nation’s vaccine policy, most of which have been made without the thorough scientific review that previously preceded changes.

Days before AAP released its new guidelines, it was hit with a lawsuit from Children’s Health Defense, the anti-vaccine group Kennedy founded and previously led, alleging that its vaccine guidance over the years amounted to a form of racketeering.

The CDC’s efforts to collect the data that typically inform public health policy have noticeably slowed under Kennedy’s leadership at HHS. A review published Monday found that of 82 CDC databases previously updated at least once a month, 38 had unexplained interruptions, with most of those pauses lasting six months or longer. Nearly 90% of the paused databases included vaccination information.

“The evidence is damning: The administration’s anti-vaccine stance has interrupted the reliable flow of the data we need to keep Americans safe from preventable infections,” Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo wrote in an editorial for Annals of Internal Medicine, a scientific journal. Marrazzo, an infectious disease specialist, was fired last year as head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases after speaking out against the administration’s public health policies.

Science

‘We’re not going away’: Rob Caughlan, fierce defender of the coastline and Surfrider leader, dies at the age of 82

Known by friends and colleagues as a “planetary patriot,” a “happy warrior” and the “Golden State Eco-Warrior,” Rob Caughlan, a political operative, savvy public relations specialist and one of the early leaders of the Surfrider Foundation, died at his home in San Mateo, on Jan. 17. He was 82.

His wife of nearly 62 years, Diana, died four days earlier, from lung cancer.

Environmentalists, political operatives and friends responded to his death with grief but also joy as they recalled his passion, talent and sense of humor — and his drive not only to make the world a better place, but to have fun doing it.

“He’d always say that the real winner in a surfing contest was the guy who had the most fun,” said Lennie Roberts, a conservationist in San Mateo County and longtime friend of Caughlan’s. “He was true to that. It’s the way he lived.”

“When he walked into a room, he’d have a big smile on his face. He was a great — a gifted — people person,” said Dan Young, one of the original five founders of the Surfrider Foundation. The organization was cobbled together in the early 1980s by a group of Southern California surfers who felt called to protect the coastline — and their waves.

They also wanted to dispel the stereotype that surfers are lackadaisical stoners — and show the world that surfers could get organized and fight for just causes, said Roberts, citing Caughlan’s 2020 memoir, “The Surfer in the White House and Other Salty Yarns.”

Before joining Surfrider in 1986, Caughlan was a political operative who worked as an environmental adviser in the Carter administration. According to Warner Chabot, an old friend and recently retired executive director of the an Francisco Estuary Institute, Caughlan got his start during the early 1970s when he and his friend, David Oke, formed the Sam Ervin Fan Club, which supported the Southern senator’s efforts to lead the Watergate investigation of President Nixon.

According to Chabot, Caughlan organized the printing of T-shirts with Ervin’s face on them, underneath the text “I Trust Uncle Sam.”

“He was an early social influencer — par extraordinaire,” he said.

Glenn Hening, a surfer, former Jet Propulsion Laboratory space software engineer and another original founder of the Surfrider Foundation, said one of the group’s initial fights was against the city of Malibu, which in the early 1980s was periodically digging up sand in the lagoon right offshore and destroying the waves at one of their favorite surf spots.

According to Hening, it was Caughlin’s unique ability to persuade and charm politicians and donors that put Surfrider’s efforts on the map.

Caughlan served as the foundation’s president from 1986 to 1992.

The foundation grabbed the national spotlight in 1989 when it went after two large paper mills in Humboldt Bay that were discharging toxic wastewater into an excellent surfspot in Northern California. The foundation took aim and in 1991 filed suit alongside the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; the paper mills settled for $5.8 million.

Hening said the victory would never have happened without Caughlan.

The mills had tried to brush off the suit by offering a donation to the foundation, Hening said. But Caughlan and Mark Massara — an environmental lawyer with the organization — rebuffed the gesture.

“The paper mill guys said, ‘Well, what can we do here? How can we make this go away?’” said Hening, recalling the conversation. “And Rob said, ‘It’s not going to go away. We’re not going away. We’re surfers.”

Roberts said Caughlan’s legacy can be felt by anyone who has ever spent time on the San Mateo County coastline. In the 1980s, the two spearheaded a successful ballot measure still protects the coast from non-agricultural development and ensured access to the beaches and bluffs. It also prohibits onshore oil facilities for off-shore facilities.

The two also worked on a county measure that led to the development of the Devil’s Slide tunnels on Highway 1 between Pacifica and Montara, designed to make that formerly treacherous path safer for travelers.

The state had wanted to build a six-lane highway over the steep hills in the area. “It would have been dangerous because of the steep slopes, and it would be going up into the fog bank and then back down out of the fog. So it was inherently dangerous,” Roberts said.

Chad Nelsen, the current president of the Surfrider Foundation, said he was first drawn into Caughlan’s orbit in 2010 when Surfrider got involved with a lawsuit pertaining to a beach in San Mateo County. Silicon Valley venture capitalist Vinod Khosla purchased 53 acres of Northern California coastline for $32.5 million and closed off access to the public — including a popular stretch known as Martin’s Beach — so Surfrider sued.

Nelsen said that although Caughlan had left the organization about 20 years before, he reappeared with a “sort of unbridled enthusiasm and commitment to the cause,” and the organization ultimately prevailed — the public can once again access the beach “thanks to ‘Birdlegs.’”

Birdlegs was Caughlan’s nickname, and according to Nelsen, it was probably coined in the 1970s by his fellow surfers.

“He had notoriously spindly legs, I guess,” Nelsen said.

Robert Willis Caughlan was born in Alliance, Ohio, on Feb. 27, 1943. His father, who was a parachute instructor with the U.S. Army, died when Caughlan was 4. In 1950, Caughlan moved with his mother and younger brother to San Mateo, where he saw the ocean for the first time.

He rode his his first wave in 1959, at the age of 16, from the breakwater at Half Moon Bay.

Science

LAUSD says Pali High is safe for students to return to after fire. Some parents and experts have concerns

The Los Angeles Unified School District released a litany of test results for the fire-damaged Palisades Charter High School ahead of the planned return of students next week, showing the district’s remediation efforts have removed much of the post-fire contamination.

However, some parents remain concerned with a perceived rush to repopulate the campus. And while experts commended the efforts as one of the most comprehensive post-fire school remediations in modern history, they warned the district failed to test for a key family of air contaminants that can increase cancer risk and cause illness.

“I think they jumped the gun,” said a parent of one Pali High sophomore, who asked not to be named because she feared backlash for her child. “I’m quite angry, and I’m very scared. My kid wants to go back. … I don’t want to give him too much information because he has a lot of anxiety around all of these changes.”

Nevertheless, she still plans to send her child back to school on Tuesday, because she doesn’t want to create yet another disruption to the student’s life. “These are kids that also lived through COVID,” she said.

The 2025 Palisades fire destroyed multiple buildings on Pali High’s campus and deposited soot and ash in others. Following the fire, the school operated virtually for several months and, in mid-April of 2025, moved into a former Sears department store in Santa Monica.

Meanwhile, on campus, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cleared debris from the destroyed structures, and LAUSD hired certified environmental remediation and testing companies to restore the still-standing buildings to a safe condition.

LAUSD serves as the charter school’s landlord and took on post-fire remediation and testing for the school. The decision to move back to the campus was ultimately up to the charter school’s independent leadership.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power tested the drinking water for a slew of contaminants, and environmental consultants tested the soil, HVAC systems, indoor air and surfaces including floors, desks and lockers.

They tested for asbestos, toxic metals such as lead and potentially hazardous organic compounds often unleashed through combustion, called volatile organic compounds, or VOCs.

“The school is ready to occupy,” said Carlos Torres, director of LAUSD’s office of environmental health and safety. “This is really the most thorough testing that’s ever been done that I can recall — definitely after a fire.”

Construction workers rebuild the Palisades Charter High School swimming pool.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

A handful of soil samples had metal concentrations slightly above typical post-fire cleanup standards, which are designed to protect at-risk individuals over many years of direct exposure to the soil — such as through yard work or playing sports. An analysis by the environmental consultants found the metals did not pose a health risk to students or staff.

On indoor surfaces, the consultants found two areas with lead and one with arsenic, spaces they recleaned and retested to make sure those metals were no longer present.

The testing for contamination in the air, however, has become a matter of debate.

Some experts cautioned that LAUSD’s consultants tested the air for only a handful of mostly non-hazardous VOCs that are typically used to detect smoke from a wildfire that primarily burned plants. While those tests found no contamination, the consultants did not test for a more comprehensive panel of VOCs, including many hazardous contaminants commonly found in the smoke of urban fires that consume homes, cars, paints, detergents and plastics.

The most notorious of the group is benzene, a known carcinogen.

At a Wednesday webinar for parents and students, LAUSD’s consultants defended the decision, arguing their goal was only to determine whether smoke lingered in the air after remediation, not to complete more open-ended testing of hazardous chemicals that may or may not have come from the fire.

Andrew Whelton, a Purdue University professor who researches environmental disasters, didn’t find the explanation sufficient.

“Benzene is known to be released from fire. It is known to be present in air. It is known to be released from ceilings and furniture and other things over time, after the fire is out,” Whelton said. “So, I do not understand why testing for benzene and some of the other fire-related chemicals was not done.”

For Whelton, it’s representative of a larger problem in the burn areas: With no decisive guidance on how to remediate indoor spaces after wildland-urban fires, different consultants are making significantly different decisions about what to test for.

LAUSD released the testing results and remediation reports in lengthy PDFs less than two weeks before students plan to return to campus, while the charter school’s leadership decided on a Jan. 27 return date before testing was completed.

At the webinar, school officials said two buildings near the outdoor pool have not yet been cleared through environmental testing and will remain closed. Four water fixtures are also awaiting final clearance from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, and the school’s food services are still awaiting certification from the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

For some parents — even those who are eager to ditch the department store campus — it amounts to a flurried rush to repopulate Pali High’s campus that is straining their decisions about how to keep their kids safe.

Torres stressed that his team acted cautiously in the decision to authorize the school for occupancy, and that promising preliminary testing helped school administrators plan ahead. He also noted that the slow, cautious approach was a point of contention for other parents who hoped their students could return to the campus as quickly as possible.

Experts largely praised LAUSD’s efforts as thorough and comprehensive — with the exception of the VOC air testing.

Remediation personnel power washed the exterior of buildings, wiped down all surfaces and completed thorough vacuuming with filters to remove dangerous substances. Any soft objects such as carpet or clothing that could absorb and hold onto contamination were discarded. The school’s labyrinth of ducts and pipes making up the HVAC system was also thoroughly cleaned.

Crews tested throughout the process to confirm their remediation work was successful and isolated sections of buildings once the work was complete. They then completed another full round of testing to ensure isolated areas were not recontaminated by other work.

Environmental consultants even determined a few smaller buildings could not be effectively decontaminated and consequently had them demolished.

Torres said LAUSD plans to conduct periodic testing to monitor air in the school, and that the district is open to parents’ suggestions.

For Whelton, the good news is that the school could easily complete comprehensive VOC testing within a week, if it wanted to.

“They are very close at giving the school a clean bill of health,” he said. “Going back and conducting this thorough VOC testing … would be the last action that they would need to take to determine whether or not health risks remain for the students, faculty and visitors.”

-

Illinois6 days ago

Illinois6 days agoIllinois school closings tomorrow: How to check if your school is closed due to extreme cold

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoMiami’s Carson Beck turns heads with stunning admission about attending classes as college athlete

-

Pittsburg, PA1 week ago

Pittsburg, PA1 week agoSean McDermott Should Be Steelers Next Head Coach

-

Lifestyle1 week ago

Lifestyle1 week agoNick Fuentes & Andrew Tate Party to Kanye’s Banned ‘Heil Hitler’

-

Pennsylvania2 days ago

Pennsylvania2 days agoRare ‘avalanche’ blocks Pennsylvania road during major snowstorm

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoMiami star throws punch at Indiana player after national championship loss

-

Cleveland, OH1 week ago

Cleveland, OH1 week agoNortheast Ohio cities dealing with rock salt shortage during peak of winter season

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoRing claims it’s not giving ICE access to its cameras