Science

SoCal officials unleash sterile mosquitoes in bid to curb disease — with promising results

A battle is underway against an invasive mosquito behind a recent surge in the local spread of dengue fever in Southern California — and officials may have unlocked a powerful tool to help win the day.

Two vector control districts — local agencies tasked with controlling disease-spreading organisms — released thousands of sterile male mosquitoes in select neighborhoods, with one district starting in 2023 and the other beginning the following year.

The idea was to drive down the mosquito population because eggs produced by a female after a romp with a sterile male don’t hatch. And only female mosquitoes bite, so unleashing males doesn’t lead to transmission of diseases such as dengue, a potentially fatal viral infection.

The data so far are encouraging.

One agency serving a large swath of Los Angeles County found a nearly 82% reduction in its invasive Aedes aegypti mosquito population in its release area in Sunland-Tujunga last year compared with a control area.

Another district, covering the southwestern corner of San Bernardino County, logged an average decrease of 44% across several heavily infested places where it unleashed the sterile males last year, compared with pre-intervention levels.

Overall invasive mosquito counts dropped 33% across the district — marking the first time in roughly eight years that the population went down instead of up.

“Not only were we out in the field and actually seeing good reductions, but we were getting a lot less calls — people calling in to complain,” said Brian Reisinger, community outreach coordinator for the Inland Empire’s West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District.

But challenges remain. Scaling the intervention to the level needed to make a dent in the vast region served by the L.A. County district won’t happen overnight and would potentially require its homeowners to pay up to $20 in an annual property tax assessment to make it happen.

Climate change is allowing Aedes mosquitoes — and diseases they spread — to move into new areas and go gangbusters in places where they’re established.

Surging dengue abroad and the widespread presence of Aedes mosquitoes at home is “creating this perfect recipe for local transmission in our region,” said Dr. Aiman Halai, director of the vector-borne disease unit at the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

Tiny scourge, big threat

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were first detected in California about a decade ago. Originally hailing from Africa, the species can transmit dengue, as well as yellow fever, Zika and chikungunya.

Another invasive mosquito, Aedes albopictus, arrived earlier, but its numbers have declined and it is less likely to spread diseases such as dengue.

Although the black-and-white striped Aedes aegypti can’t fly far — just about 150 to 200 yards — they manage to get around. The low-flying, day-biting mosquitoes are present in more than a third of California’s counties, including Shasta County in the far north.

An Aedes mosquito, known for nipping ankles, prefers to bite humans over animals. The insects, which arrived in California about a decade ago, can transmit diseases such as dengue and Zika.

(Orange County Mosquito and Vector Control District)

Aedes mosquitoes love to bite people — often multiple times in rapid succession. As the insects spread across the state, patios and backyards morphed from respites into risky territories.

But tamping down the bugs has proved difficult. They can lay their eggs in tiny water sources. And they might lay a few in a plant tray and others, perhaps, in a drain. Annihilating invaders isn’t easy when it can be hard to locate all the reproduction spots — or access all the yards where breeding is rampant.

That’s one of the reasons why releasing sterilized males is attractive: They’re naturally adept at finding their own kind.

Mosquito vs. mosquito

Releasing sterilized male insects to combat pests is a proven scientific technique that’s been around since the 1950s, but using it to control invasive mosquitoes is relatively new. The approach appears to be catching on in Southern California.

The West Valley district pioneered the release of sterilized male mosquitoes in California. In 2023, the Ontario-based agency rolled out a pilot program before expanding it the following year. This year it is increasing the number of sites being treated.

The Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control District launched its own pilot effort in 2024 and plans to target roughly the same area this year — with some improvements in technique and insect-rearing capacity.

Starting in late May, an Orange County district will follow suit with the planned release of 100,000 to 200,000 sterile male mosquitoes a week in Mission Viejo through November. A Coachella Valley district is plugging away at developing its own program, which could get off the ground next spring.

Vector officials in L.A. and San Bernardino counties said residents are asking them when they can bring a batch of zapped males to their neighborhood. But experts say for large population centers, it’s not that easy.

“I just responded this morning to one of our residents that says, ‘Why can’t we have this everywhere this year?’ And it’s, of course, because Rome wasn’t built in a day,” said Susanne Kluh, general manager for the Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control District.

Kluh’s district has a budget of nearly $24 million and is responsible for nearly 6 million residents across 36 cities and unincorporated areas. West Valley’s budget this fiscal year is roughly $4 million, and the district serves roughly 650,000 people in six cities and surrounding county areas.

Approaches between the two districts differ, in part due to the scale they’re working with.

West Valley targets what it calls hot spots — areas with particularly high mosquito counts. Last year, before peak mosquito season, it released about 1,000 sterile males biweekly per site. Then the district bumped it to up to 3,000 for certain sites for the peak period, which runs from August to November. The idea is to outnumber wild males by 100 to 1. Equipment for the program cost about $200,000 and the district hired a full-time staffer to assist with the efforts this year for $65,000.

Solomon Birhanie, scientific director for West Valley, said the district doesn’t have the resources to attack large tracts of land so it’s using the resources it does have efficiently. Focusing on problem sites has shown to be sufficient to affect the whole service area, he said.

“Many medium to smaller districts are now interested to use our approach,” he said, because there’s now evidence that it can be incorporated into abatement programs “without the need for hiring highly skilled personnel or demanding a larger amount of budget.”

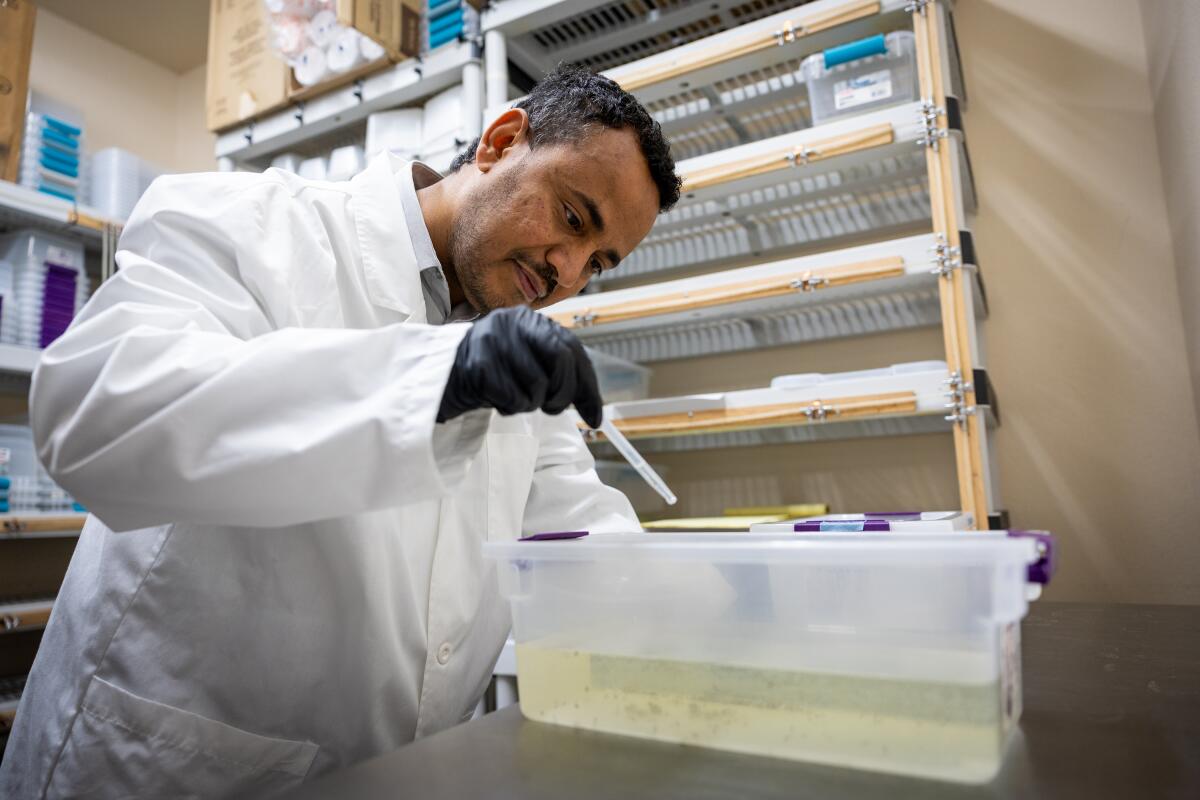

Solomon Birhanie, scientific director at the West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District, views a container of mosquito larvae in the lab in March 2024. The Ontario-based district pioneered the release of sterilized male Aedes mosquitoes in California.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In its inaugural study last year, the L.A. County district unleashed an average of 30,000 males per week in two Sunland-Tujunga neighborhoods between May and October — seeking to outperform wild males 10 to 1. Kluh anticipates this year’s pilot will cost about $350,000.

In order to bring the program to a larger area of the district, Kluh said more funding is needed — with officials proposing up to $20 annually per single-family home. That would be in addition to the $18.97 district homeowners now pay for the services the agency already provides.

If surveys sent to a sample of property owners favor the new charge, it’ll go to a vote in the fall, as required by Proposition 218, Kluh said.

There are five vector control districts that cover L.A. County. The Greater L.A. County district is the largest, stretching from San Pedro to Santa Clarita. It covers most of L.A. city except for coastal regions and doesn’t serve the San Gabriel or Antelope valleys.

Galvanized by disease

California last year had 18 locally acquired dengue cases, meaning people were infected with the viral disease in their communities, not while traveling.

Fourteen of those cases were in Los Angeles County, including at least seven tied to a small outbreak in Baldwin Park, a city east of L.A. Cases also cropped up in Panorama City, El Monte and the Hollywood Hills.

The year before that, the state confirmed its first locally acquired cases, in Long Beach and Pasadena.

Although most people with dengue have no symptoms, it can cause severe body aches and fever and, in rare cases, death. Its alias, “breakbone fever,” provides a grim glimpse into what it can feel like.

Over a third of L.A. County’s dengue cases last year required hospitalization, according to Halai.

Mosquitoes pick up the virus after they bite an infected person, then spread it by biting others.

Hope and hard truths

Mosquito control experts tout sterilization for being environmentally friendly because it doesn’t involve spraying chemicals and officials could potentially use it to target other disease spreaders — such as the region’s native Culex mosquito, a carrier of the deadly West Nile virus.

New technologies continue to come online. In the summer last year, the California Department of Pesticide Regulation approved the use of male mosquitoes infected with a particular strain of a bacteria called Wolbachia. Eggs fertilized by those males also don’t hatch.

Despite the promising innovations, some aspects of the scourge defy local control.

Since her start in mosquito control in California nearly 26 years ago, Kluh said, the season for the insects has lengthened as winters have become shorter. Back then, officials would get to work in late April or early May and wrap up around early October. Now the native mosquitoes emerge as early as March and the invasive insects can stick around into December.

“If things are going the way it is going now, we could just always have some dengue circulating,” she said.

Last year marked the worst year on record for dengue globally, with more than 13 million cases reported in the Americas and the Caribbean, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Many countries are still reporting higher-than-average dengue numbers, meaning there’s more opportunity for travelers to bring it home.

Science

Can fire-resistant homes be sexy? ‘You be the judge,’ says this Palisades architect

At first glance, it looks like nothing more than a charming Spanish-revival, quintessentially Californian home — but this Pacific Palisades rebuild is constructed like a tank.

Every exterior wall of the steel-framed home is a foot-thick, fire-resistant barricade. The home is connected to a satellite fire monitoring service. Should a fire start in town, sturdy metal shutters descend to cover every window. An exterior sprinkler system can pump 40,000 gallons of water from giant tanks hidden behind the shrubs in the property’s yard. If the cameras and heat sensors around the house detect danger, the system can envelop the home in over 1,000 gallons of fire retardant and hundreds of gallons of fire-suppressing foam.

Palisades resident and architect Ardie Tavangarian is so confident in his design that he even asked the fire department if they could start a controlled fire on the property to test it all out. (They said no.)

Tavangarian built a career designing multimillion-dollar luxury homes in Los Angeles, but after the Palisades fire destroyed 13 of his works — including his family’s home — he found another calling: how to design a house that can handle what the Santa Monica Mountains throw at it. And how to do it quickly and affordably.

Water tanks form part of a backup water supply in a newly built fire-resistant home in Pacific Palisades.

“Nature is so powerful,” he said, sitting on a couch in the new house, which he built for his adult twin daughters. “We are guests living in that environment and expecting, ‘Oh, nature is going to be really kind to me.’ No, it’s not. It does what it’s supposed to do.”

Tavangarian watched the Jan. 1 Lachman fire from his property not far from here; a week later that fire rekindled, grew into the Palisades fire, and burned through his house. But the painful details of the fire — the missteps of the fire department, the empty reservoir — didn’t matter when it came to deciding how to rebuild, he said. The reality is, many fires have burned in these mountains. Many more will.

A sprinkler on the roof is part of a house-wide sprinkler system.

For the architect, who has spent much of his 45-year career designing for luxury, hardening a home against wildfire has brought a new kind of luxury to his homes: peace of mind.

It’s a sentiment that resonates with fire survivors: Tavangarian says he’s received considerable interest from other property owners in the Palisades looking to rebuild their houses.

The metal shutters and advanced outdoor sprinkler system are the flashiest parts of Tavangarian’s home hardening project, and the efficacy of these adaptations is still up for debate. Because the measures have not yet been widely adopted, there are few studies exploring how much or little they protect homes in real-world fires.

Architect Ardie Tavangarian inside the house he designed.

Anecdotal evidence has indicated the effectiveness of sprinklers can vary significantly based on the setup and the conditions during the fire. Extreme wind, for example, can make them less effective. Lab studies have generally found shutters can reduce the risk of windows shattering.

These measures aren’t cheap, either. Sprinkler systems can cost north of $100,000, for example. However, Tavangarian said when all was said and done, the home he built for his daughters cost around $700 per square foot — less than what Palisades residents said they expected to pay, but more than what Altadena residents expected for their rebuilds.

Tavangarian also hopes to see insurers increasingly consider the home-hardening measures property owners take when writing policies, which he said could potentially offset the extra cost in a decade or less. As he explored getting insurance for the new home, one insurer quoted him $80,000 a year. After he convinced the company to visit the property, it lowered the quote to just $13,000, he said.

The house includes metal heat shields that can drop down if a fire approaches.

The home also has essentially all of the other less flashy — but much cheaper and well-proven — home hardening measures recommended by fire professionals: The underside of the roof’s overhang is closed off — a common place embers enter a home. The roof, where burning embers can accumulate, is made of fire-resistant material. The windows, vulnerable to shattering in extreme heat, are made of a toughened glass. There is virtually no vegetation within the first five feet of the home.

When asked if he felt he had compromised on design, comfort or aesthetics for the extra protection — one of the many concerns Californians have with the state’s draft “Zone Zero” requirements that may significantly limit vegetation within five feet of a home — Tavangarian simply said, “You be the judge.”

Science

Commentary: My toothache led to a painful discovery: The dental care system is full of cavities as you age

I had a nagging toothache recently, and it led to an even more painful revelation.

If you X-rayed the state of oral health care in the United States, particularly for people 65 and older, the picture would be full of cavities.

“It’s probably worse than you can even imagine,” said Elizabeth Mertz, a UC San Francisco professor and Healthforce Center researcher who studies barriers to dental care for seniors.

Mertz once referred to the snaggletoothed, gap-filled oral health care system — which isn’t really a system at all — as “a mess.”

But let me get back to my toothache, while I reach for some painkiller. It had been bothering me for a couple of weeks, so I went to see my dentist, hoping for the best and preparing for the worst, having had two extractions in less than two years.

Let’s make it a trifecta.

My dentist said a molar needed to be yanked because of a cellular breakdown called resorption, and a periodontist in his office recommended a bone graft and probably an implant. The whole process would take several months and cost roughly the price of a swell vacation.

I’m lucky to have a great dentist and dental coverage through my employer, but as anyone with a private plan knows, dental insurance can barely be called insurance. It’s fine for cleanings and basic preventive routines. But for more complicated and expensive procedures — which multiply as you age — you can be on the hook for half the cost, if you’re covered at all, with annual payout caps in the $1,500 range.

“The No. 1 reason for delayed dental care,” said Mertz, “is out-of-pocket costs.”

So I wondered if cost-wise, it would be better to dump my medical and dental coverage and switch to a Medicare plan that costs extra — Medicare Advantage — but includes dental care options. Almost in unison, my two dentists advised against that because Medicare supplemental plans can be so limited.

Sorting it all out can be confusing and time-consuming, and nobody warns you in advance that aging itself is a job, the benefits are lousy, and the specialty care you’ll need most — dental, vision, hearing and long-term care — are not covered in the basic package. It’s as if Medicare was designed by pranksters, and we’re paying the price now as the percentage of the 65-and-up population explodes.

So what are people supposed to do as they get older and their teeth get looser?

A retired friend told me that she and her husband don’t have dental insurance because it costs too much and covers too little, and it turns out they’re not alone. By some estimates, half of U.S. residents 65 and older have no dental insurance.

That’s actually not a bad option, said Mertz, given the cost of insurance premiums and co-pays, along with the caps. And even if you’ve got insurance, a lot of dentists don’t accept it because the reimbursements have stagnated as their costs have spiked.

But without insurance, a lot of people simply don’t go to the dentist until they have to, and that can be dangerous.

“Dental problems are very clearly associated with diabetes,” as well as heart problems and other health issues, said Paul Glassman, associate dean of the California Northstate University dentistry school.

There is one other option, and Mertz referred to it as dental tourism, saying that Mexico and Costa Rica are popular destinations for U.S. residents.

“You can get a week’s vacation and dental work and still come out ahead of what you’d be paying in the U.S.,” she said.

Tijuana dentist Dr. Oscar Ceballos told me that roughly 80% of his patients are from north of the border, and come from as far away as Florida, Wisconsin and Alaska. He has patients in their 80s and 90s who have been returning for years because in the U.S. their insurance was expensive, the coverage was limited and out-of-pocket expenses were unaffordable.

“For example, a dental implant in California is around $3,000-$5,000,” Ceballos said. At his office, depending on the specifics, the same service “is like $1,500 to $2,500.” The cost is lower because personnel, office rent and other overhead costs are cheaper than in the U.S., Ceballos said.

As we spoke by phone, Ceballos peeked into his waiting room and said three patients were from the U.S. He handed his cellphone to one of them, San Diegan John Lane, who said he’s been going south of the border for nine years.

“The primary reason is the quality of the care,” said Lane, who told me he refers to himself as 39, “with almost 40 years of additional” time on the clock.

Ceballos is “conscientious and he has facilities that are as clean and sterile and as medically up to date as anything you’d find in the U.S.,” said Lane, who had driven his wife down from San Diego for a new crown.

“The cost is 50% less than what it would be in the U.S.,” said Lane, and sometimes the savings is even greater than that.

Come this summer, Lane may be seeing even more Californians in Ceballos’ waiting room.

“Proposed funding cuts to the Medi-Cal Dental program would have devastating impacts on our state’s most vulnerable residents,” said dentist Robert Hanlon, president of the California Dental Assn.

Dental student Somkene Okwuego smiles after completing her work on patient Jimmy Stewart, 83, who receives affordable dental work at the Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC on the USC campus in Los Angeles on February 26, 2026.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Under Proposition 56’s tobacco tax in 2016, supplemental reimbursements to dentists have been in place, but those increases could be wiped out under a budget-cutting proposal. Only about 40% of the state’s dentists accept Medi-Cal payments as it is, and Hanlon told me a CDA survey indicates that half would stop accepting Medi-Cal patients and many others will accept fewer patients.

“It’s appalling that when the cost of providing healthcare is at an all-time high, the state is considering cutting program funding back to 1990s levels,” Hanlon said. “These cuts … will force patients to forgo or delay basic dental care, driving completely preventable emergencies into already overcrowded emergency departments.”

Somkene Okwuego, who as a child in South L.A. was occasionally a patient at USC’s Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry clinic, will graduate from the school in just a few months.

I first wrote about Okwuego three years ago, after she got an undergrad degree in gerontology, and she told me a few days ago that many of her dental patients are elderly and have Medi-Cal or no insurance at all. She has also worked at a Skid Row dental clinic, and plans after graduation to work at a clinic where dental care is free or discounted.

Okwuego said “fixing the smiles” of her patients is a privilege and boosts their self-image, which can help “when they’re trying to get jobs.” When I dropped by to see her Thursday, she was with 83-year-old patient Jimmy Stewart.

Stewart, an Army veteran, told me he had trouble getting dental care at the VA and had gone years without seeing a dentist before a friend recommended the Ostrow clinic. He said he’s had extractions and top-quality restorative care at USC, with the work covered by his Medi-Cal insurance.

I told Stewart there could be some Medi-Cal cuts in the works this summer.

“I’d be screwed,” he said.

Him and a lot of other people.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

Science

Diablo Canyon clears last California permit hurdle to keep running

Central Coast Water authorities approved waste discharge permits for Diablo Canyon nuclear plant Thursday, making it nearly certain it will remain running through 2030, and potentially through 2045.

The Pacific Gas & Electric-owned plant was originally supposed to shut down in 2025, but lawmakers extended that deadline by five years in 2022, fearing power shortages if a plant that provides about 9 percent the state’s electricity were to shut off.

In December, Diablo Canyon received a key permit from the California Coastal Commission through an agreement that involved PG&E giving up about 12,000 acres of nearby land for conservation in exchange for the loss of marine life caused by the plant’s operations.

Today’s 6-0 vote by the Central Coast Regional Water Board approved PG&E’s plans to limit discharges of pollutants into the water and continue to run its “once-through cooling system.” The cooling technology flushes ocean water through the plant to absorb heat and discharges it, killing what the Coastal Commission estimated to be two billion fish each year.

The board also granted the plant a certification under the Clean Water Act, the last state regulatory hurdle the facility needed to clear before the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is allowed to renew its permit through 2045.

The new regional water board permit made several changes since the last one was issued in 1990. One was a first-time limit on the chemical tributyltin-10, a toxic, internationally-banned compound added to paint to prevent organisms from growing on ship hulls.

Additional changes stemmed from a 2025 Supreme Court ruling that said if pollutant permits like this one impose specific water quality requirements, they must also specify how to meet them.

The plant’s biggest water quality impact is the heated water it discharges into the ocean, and that part of the permit remains unchanged. Radioactive waste from the plant is regulated not by the state but by the NRC.

California state law only allows the plant to remain open to 2030, but some lawmakers and regulators have already expressed interest in another extension given growing electricity demand and the plant’s role in providing carbon-free power to the grid.

Some board members raised concerns about granting a certification that would allow the NRC to reauthorize the plant’s permits through 2045.

“There’s every reason to think the California entities responsible for making the decision about continuing operation, namely the California [Independent System Operator] and the Energy Commission, all of them are sort of leaning toward continuing to operate this facility,” said boardmember Dominic Roques. “I’d like us to be consistent with state law at least, and imply that we are consistent with ending operation at five years.”

Other board members noted that regulators could revisit the permits in five years or sooner if state and federal laws changes, and the board ultimately approved the permit.

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO6 days ago

Denver, CO6 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Oregon4 days ago

Oregon4 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoArturia’s FX Collection 6 adds two new effects and a $99 intro version