Science

Marine mammals are dying in record numbers along the California coast

DAVENPORT, Calif. — On a spit of sand 12 miles north of Santa Cruz, a small, emaciated sea lion lay on its side. The only sign of life was the deep press of its flippers against its belly, relaxing for a few seconds, then squeezing again.

“That’s a classic sign of lepto,” said Giancarlo Rulli, a volunteer and spokesperson with the Marine Mammal Center, pointing to the young animal’s wretched self-embrace. The corkscrew-shaped bacteria, leptospirosis, causes severe abdominal pain in sea lions by damaging their kidneys and inflaming their gastrointestinal tracts. “They hold their stomach just like that. Like a sick child with a bellyache,” he said.

Since the end of June, officials say nearly 400 animals have been reported stranded or sickened along the Central Coast beaches. More than two-thirds of them have died, Rulli said. Hundreds more probably were washed away before anyone spotted them, or died at sea.

The historically large and long bacterial outbreak is adding to an already devastating death toll for the seals, sea lions, dolphins, otters and whales who live in and migrate through the state’s coastal waters.

There are the poisonous algal blooms off the central and southern coasts. There are massive changes in food availability and distribution across the Pacific. And there are growing casualties from ship strikes, record numbers of entanglements in rope and line, and a new heat blob forming in the eastern Pacific.

Members of the Marine Mammal Center contain an injured sea lion in Davenport.

(Nic Coury / For The Times)

This year may be remembered as one of the gravest for marine mammals on record. Or, more worryingly, a sign that our ocean environment is changing so drastically that in some places and seasons, it’s becoming uninhabitable for the life it holds.

The network of volunteers who tend to stranded marine life is running ragged, said Rulli, answering dozens of rescue calls a day. “It’s been a brutal year. … It’s been hard on the animals. It’s been traumatic for the volunteers. It’s a lot.”

Whether all of these pressures and changes are related, or are completely separate phenomena happening at the same time in the same place, scientists don’t know.

“We’re trying to build our understanding of how ocean conditions relate to the occurrence of disease. But it’s a work in progress. And the world is changing quickly underneath our feet,” said Jamie Lloyd-Smith, an ecologist and evolutionary biologist at UCLA.

The first outbreak of leptospirosis in sea lions was reported along the West Coast in 1970, said Katie Prager, a disease ecologist at UCLA. By the 1980s, the Marine Mammal Center and others were keeping comprehensive records. They found that the bacterium tended to cause small, annual outbreaks that started in late summer and lasted just a month or two.

Dr. Alissa Deming, left, and veterinarian assistant Malena Berndt give anti-seizure medicine to a California sea lion named Patsy in a recovery room at the Pacific Marine Mammal Center in Laguna Beach after it had seizures from toxic algae blooms in June 2023.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Every three to five years, however, they’d see a large outbreak in which scores of animals got sick. In 2011 and 2018 during the last two big outbreaks, roughly 300 animals were rescued, Rulli said.

Lloyd-Smith and others say such leptospira-booms are probably driven by typical population dynamics — such as when a large enough cohort of never-exposed young animals get it and pass it around on beaches where the highly social animals congregate.

But this year, the outbreak started more than a month earlier than usual, and the number of sickened animals has surpassed any previously recorded outbreak.

This year seems deadlier, too, Rulli said. Leptospirosis typically kills some two-thirds of the animals it sickens. It’s only an impression at this point, but this year it seems to him like even more.

Looking at the sick pup on the Davenport beach, Rulli shook his head and said the animal was about as sick as he’d ever seen.

The little sea lion was humanely put down soon after it was taken to the Marine Mammal Center’s Castroville clinic, noted on a white board only as “Nameless Carcass.”

Why this year’s outbreak has been so devastating is not clear.

Lloyd-Smith and Prager said the leptospira species that affects sea lions is also found in some terrestrial mammals — such as raccoons, skunks and coyotes. Whether these scavengers are introducing new strains of the bacteria to sea lions on beaches, or the other way around, is not known. Nor is the bacteria’s natural reservoir — an area of research Lloyd-Smith is actively pursuing.

Jeremy Alcantara of the Marine Mammal Center nets an injured sea lion on a dock in Capitola.

(Nic Coury / For The Times)

On a floating dock below the Capitola wharf, two groups of sea lions were lying down in the unusually sticky, humid air of a recent late-September afternoon. Seven were spooning one another in two small clusters — their flippers outstretched on each other’s bodies, their heads resting on their neighbors’ tummies or backs.

One rested at a distance from the others. It was the one someone had called in about.

For the rescue team, it was the third stop of the day, and it would be another tough one. A quick scan of the eight sea lions showed that another also looked unwell, her hip bones and vertebrae jutted jarringly underneath her blubberless skin.

The rescuers tried to catch the solo sea lion by nabbing her with a large fishing net, but she managed to squirt out of it. Veteran rescuers Jeremy Alcantara and Patrick McDonald regrouped with the others up on the wharf. They decided they’d try for the bony sea lion sunbathing with her friends.

Members of the Marine Mammal Center carry an injured sea lion on the pier in Capitola.

(Nic Coury / For The Times)

Since April, the state’s stranding network of volunteer rescue crews has been responding daily to calls about sick sea lions, dolphins, whales, sea turtles and birds.

On the Southern California coast, there was a historic domoic acid outbreak that sickened more than 2,100 animals.

In the Bay Area, there was a record-breaking number of dead gray whales.

And from San Diego to Crescent City, they saw an off-the-chart number of whale entanglements — humpbacks and gray whales caught in the ropes and lines of the region’s commercial fisheries.

Now there’s worry that a growing marine heat wave in the Pacific could make things even worse — just as the Trump administration has threatened to pull funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which provides financial help, research and oceanic data for the beleaguered animal crews.

“Fortunately, these volunteers don’t give up,” Rulli said. “They’re completely dedicated.”

Alcantara and McDonald descended the stairs from the wharf to the floating dock, taking roughly 10 minutes to quietly approach the sunbathing sea lions. The skinny one they were after had her flippers tucked tight against her belly.

A curious gull watched from the water. Tourists and locals gawked from above.

With a swoop of the net they caught her, carried her up the ramp to the wharf, quickly maneuvered her into a crate and then the back of an air-conditioned van that drove her to Castroville, where she was pumped with antibiotics and fluids.

She’s now at the center’s headquarters hospital in Sausalito, said Rulli. But “has not been receptive to offers of sustainable ground herring.”

Woodrow, as she has been named, is stable and the center’s veterinary staff will assess her again.

Science

AI windfall helps California narrow projected $3-billion budget deficit

SACRAMENTO — California and its state-funded programs are heading into a period of volatile fiscal uncertainty, driven largely by events in Washington and on Wall Street.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget chief warned Friday that surging revenues tied to the artificial intelligence boom are being offset by rising costs and federal funding cuts. The result: a projected $3-billion state deficit for the next fiscal year despite no major new spending initiatives.

The Newsom administration on Friday released its proposed $348.9-billion budget for the fiscal year that begins July 1, formally launching negotiations with the Legislature over spending priorities and policy goals.

“This budget reflects both confidence and caution,” Newsom said in a statement. “California’s economy is strong, revenues are outperforming expectations, and our fiscal position is stable because of years of prudent fiscal management — but we remain disciplined and focused on sustaining progress, not overextending it.”

Newsom’s proposed budget did not include funding to backfill the massive cuts to Medicaid and other public assistance programs by President Trump and the Republican-led Congress, changes expected to lead to millions of low-income Californians losing healthcare coverage and other benefits.

“If the state doesn’t step up, communities across California will crumble,” California State Assn. of Counties Chief Executive Graham Knaus said in a statement.

The governor is expected to revise the plan in May using updated revenue projections after the income tax filing deadline, with lawmakers required to approve a final budget by June 15.

Newsom did not attend the budget presentation Friday, which was out of the ordinary, instead opting to have California Director of Finance Joe Stephenshaw field questions about the governor’s spending plan.

“Without having significant increases of spending, there also are no significant reductions or cuts to programs in the budget,” Stephenshaw said, noting that the proposal is a work in progress.

California has an unusually volatile revenue system — one that relies heavily on personal income taxes from high-earning residents whose capital gains rise and fall sharply with the stock market.

Entering state budget negotiations, many expected to see significant belt tightening after the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office warned in November that California faces a nearly $18-billion budget shortfall. The governor’s office and Department of Finance do not always agree, or use the LAO’s estimates.

On Friday, the Newsom administration said it is projecting a much smaller deficit — about $3 billion — after assuming higher revenues over the next three fiscal years than were forecast last year. The gap between the governor’s estimate and the LAO’s projection largely reflects differing assumptions about risk: The LAO factored in the possibility of a major stock market downturn.

“We do not do that,” Stephenshaw said.

Among the key areas in the budget:

Science

California confirms first measles case for 2026 in San Mateo County as vaccination debates continue

Barely more than a week into the new year, the California Department of Public Health confirmed its first measles case of 2026.

The diagnosis came from San Mateo County, where an unvaccinated adult likely contracted the virus from recent international travel, according to Preston Merchant, a San Mateo County Health spokesperson.

Measles is one of the most infectious viruses in the world, and can remain in the air for two hours after an infected person leaves, according to the CDPH. Although the U.S. announced it had eliminated measles in 2000, meaning there had been no reported infections of the disease in 12 months, measles have since returned.

Last year, the U.S. reported about 2,000 cases, the highest reported count since 1992, according to CDC data.

“Right now, our best strategy to avoid spread is contact tracing, so reaching out to everybody that came in contact with this person,” Merchant said. “So far, they have no reported symptoms. We’re assuming that this is the first [California] measles case of the year.”

San Mateo County also reported an unvaccinated child’s death from influenza this week.

Across the country, measles outbreaks are spreading. Today, the South Carolina State Department of Public Health confirmed the state’s outbreak had reached 310 cases. The number has been steadily rising since an initial infection in July spread across the state and is now reported to be connected with infections in North Carolina and Washington.

Similarly to San Mateo’s case, the first reported infection in South Carolina came from an unvaccinated person who was exposed to measles while traveling internationally.

At the border of Utah and Arizona, a separate measles outbreak has reached 390 cases, stemming from schools and pediatric centers, according to the Utah Department of Health and Human Services.

Canada, another long-standing “measles-free” nation, lost ground in its battle with measles in November. The Public Health Agency of Canada announced that the nation is battling a “large, multi-jurisdictional” measles outbreak that began in October 2024.

If American measles cases follow last year’s pattern, the United States is facing losing its measles elimination status next.

For a country to lose measles-free status, reported outbreaks must be of the same locally spread strain, as was the case in Canada. As many cases in the United States were initially connected to international travel, the U.S. has been able to hold on to the status. However, as outbreaks with American-origin cases continue, this pattern could lead the Pan American Health Organization to change the country’s status.

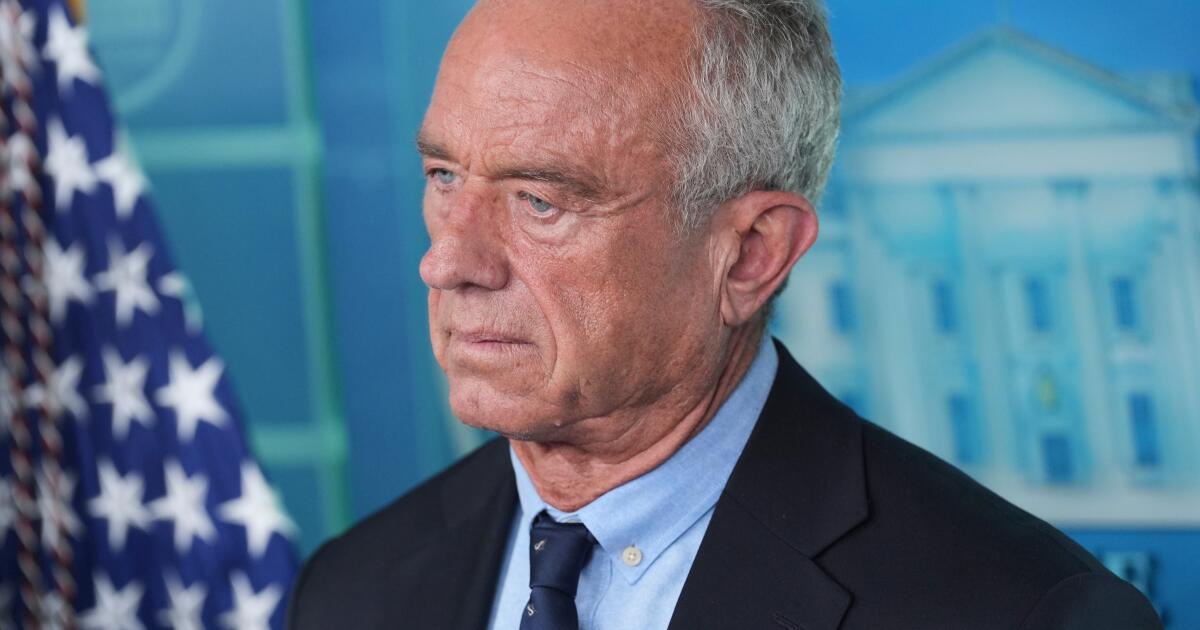

In the first year of the Trump administration, officials led by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. have promoted lowering vaccine mandates and reducing funding for health research.

In December, Trump’s presidential memorandum led to this week’s reduced recommended childhood vaccines; in June, Kennedy fired an entire CDC vaccine advisory committee, replacing members with multiple vaccine skeptics.

Experts are concerned that recent debates over vaccine mandates in the White House will shake the public’s confidence in the effectiveness of vaccines.

“Viruses and bacteria that were under control are being set free on our most vulnerable,” Dr. James Alwine, a virologist and member of the nonprofit advocacy group Defend Public Health, said to The Times.

According to the CDPH, the measles vaccine provides 97% protection against measles in two doses.

Common symptoms of measles include cough, runny nose, pink eye and rash. The virus is spread through breathing, coughing or talking, according to the CDPH.

Measles often leads to hospitalization and, for some, can be fatal.

Science

Trump administration declares ‘war on sugar’ in overhaul of food guidelines

The Trump administration announced a major overhaul of American nutrition guidelines Wednesday, replacing the old, carbohydrate-heavy food pyramid with one that prioritizes protein, healthy fats and whole grains.

“Our government declares war on added sugar,” Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said in a White House press conference announcing the changes. “We are ending the war on saturated fats.”

“If a foreign adversary sought to destroy the health of our children, to cripple our economy, to weaken our national security, there would be no better strategy than to addict us to ultra-processed foods,” Kennedy said.

Improving U.S. eating habits and the availability of nutritious foods is an issue with broad bipartisan support, and has been a long-standing goal of Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again movement.

During the press conference, he acknowledged both the American Medical Association and the American Assn. of Pediatrics for partnering on the new guidelines — two organizations that earlier this week condemned the administration’s decision to slash the number of diseases that U.S. children are vaccinated against.

“The American Medical Association applauds the administration’s new Dietary Guidelines for spotlighting the highly processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, and excess sodium that fuel heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic illnesses,” AMA president Bobby Mukkamala said in a statement.

-

Detroit, MI1 week ago

Detroit, MI1 week ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX4 days ago

Dallas, TX4 days agoAnti-ICE protest outside Dallas City Hall follows deadly shooting in Minneapolis

-

Delaware3 days ago

Delaware3 days agoMERR responds to dead humpback whale washed up near Bethany Beach

-

Dallas, TX1 week ago

Dallas, TX1 week agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Iowa6 days ago

Iowa6 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Montana2 days ago

Montana2 days agoService door of Crans-Montana bar where 40 died in fire was locked from inside, owner says

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits