Science

Inside the plan to diagnose Alzheimer’s in people with no memory problems — and who stands to benefit

In a darkened Amsterdam conference hall this summer, a panel of industry and academic scientists took the stage to announce a plan to radically expand the definition of Alzheimer’s disease to include millions of people with no memory complaints.

Those with normal cognition who test positive for elevated levels of certain proteins that have been tied to Alzheimer’s — but not proven to cause the disease — would be diagnosed as having Alzheimer’s Stage 1, the panel members explained.

Even before the presentation ended, attendees in the packed hall were lining up behind microphones to ask questions, according to video of the event.

“I’m troubled by this,” Dr. Andrea Bozoki, a University of North Carolina neurologist, told the panel. “You are taking a bunch of people who may never develop dementia or even cognitive impairment and you’re calling them Stage 1. That doesn’t seem to fit.”

Under the proposal, tens of millions of Americans with normal cognition would test positive for abnormal levels of amyloid or tau, the two proteins the tests look for, and the majority of them may never be diagnosed with dementia, studies suggest. A 60-year-old man who tests positive, for example, is estimated to have a 23% risk of developing dementia in his lifetime.

Criticism of the plan has intensified since it was unveiled in July at the international conference attended by 11,000 doctors and scientists. But the panel, organized by the nonprofit Alzheimer’s Assn., is continuing its push to extend the diagnosis to people who have no problem recalling events or what day it is — and convince skeptics that Alzheimer’s symptoms aren’t necessary to have the disease.

Panel members argue that the earlier patients get help, the more effective it might be. The availability of new drugs for patients with early Alzheimer’s symptoms has spurred them into action now, they say.

The plan could be approved by the panel and published in a medical journal early this year, association officials said. Such a move is likely to be influential: A similar proposal in 2018 that was put forth to help guide research on experimental Alzheimer’s medications was quickly adopted by the Food and Drug Administration and is frequently cited by doctors, scientists and health insurers.

Standing to benefit are the pharmaceutical and medical testing companies who employ seven members of the 20-person panel. At least seven more members of the panel are academics who receive money from those companies for consulting or research. Panelists reached by The Times said the funding did not influence their decisions.

Four other scientists who are outside advisors to the panel are executives from Eisai and Biogen, the makers of two new medicines for Alzheimer’s patients, and Eli Lilly and Genentech, which are developing similar drugs.

The American Geriatrics Society called the panel members’ financial ties to industry “wholly inappropriate.” In an analysis of the proposal, the society warned the proposal could lead to overdiagnosis of Alzheimer’s and subject people to treatments with “limited benefit and high potential for harm.”

Others said the plan was premature at best.

“I think this is untested, uncharted territory,” said Dr. Madhav Thambisetty, a senior researcher at the National Institute of Aging. “I’m not at that stage where I would be able to make a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in somebody who’s cognitively normal based on the presence of a single biomarker.”

A researcher at Washington University in St. Louis works on a blood test for Alzheimer’s disease.

(Huy Mach / University of Washington via Associated Press)

Under the proposal, people with no memory problems who test positive for abnormal levels of amyloid or tau proteins would be classified as Stage 1. They would move to Stage 2 if they begin to experience “neurobehavioral difficulties” such as depression, anxiety or apathy — symptoms often unrelated to Alzheimer’s — even if the patient’s cognition is unchanged.

Stage 3 would be for those with mild cognitive impairment, while Stages 4 through 6 would describe patients with mild, moderate or severe dementia.

The move to label more Americans as having Alzheimer’s comes amid a decades-long decline in the risk of dementia. Researchers don’t know why the risk is falling, but they say higher levels of education, a reduction in smoking and better treatment of high blood pressure could all be factors.

Dr. Peter Whitehouse, professor of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, is one of several doctors who have noted that the plan could benefit the Alzheimer’s Assn. since the majority of its donations come from people who know one of the estimated 6.7 million Americans now living with the disease and want to help find a cure. If more Americans are diagnosed with the disease under the new definition, the ranks of possible donors would swell, he said.

“This raises the potential for more people to want to give money,” Whitehouse added.

The panel said it was proposing the changes now because the FDA has approved two drugs — Eisai’s Leqembi and Aduhelm from Biogen — for patients in the early stages of memory decline. While a study of Leqembi’s effects on asymptomatic people has begun, there is currently no evidence that giving it to people without cognitive impairment can reduce the risk of dementia or delay the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Another reason for the change, the panel said, was the availability of new blood tests that do an “excellent” job of detecting abnormal levels of amyloid and tau in the brain. The blood tests are easier and less invasive than the PET scans and spinal taps that traditionally have been used to measure levels of Alzheimer’s-related proteins.

“The purpose of this initiative is to advance the science of early detection and treatment,” said panel member Maria Carrillo, the Alzheimer Assn.’s chief science officer. “In order to prevent dementia, we need to detect and treat the disease before symptoms appear.”

Thambisetty and other doctors also note that the plan does not address the serious bioethical concerns that come with testing healthy people for signs of Alzheimer’s.

People with no memory problems who learn they are positive for abnormal levels of amyloid or tau proteins can suffer from depression, anxiety and thoughts of suicide, studies have found.

A doctor points to PET scan results that are part of a study on Alzheimer’s disease at a hospital in Washington.

(Evan Vucci / Associated Press)

A positive test can also lead to discrimination by employers and by companies offering life, disability and long-term care insurance. That risk is so real that people with no memory complaints who volunteer for an ongoing clinical trial that requires an amyloid test are advised to consider getting any insurance they’ve been contemplating before taking the test.

“This is an ethically gray area,” Thambisetty said of testing cognitively normal people. “There are many questions that remain to be answered.”

Added Dr. Eric Widera, a geriatrician at UC San Francisco: “If somebody tests positive for amyloid and they are an airplane pilot, do they have to disclose that to the airlines? They are not asking these questions.”

Concerns like these led the panel members to revise the draft to say they were not yet advocating for “routine” testing of those without memory problems. And Dr. Clifford R. Jack Jr., a radiologist at the Mayo Clinic who leads the panel, told The Times the proposal was not an instruction manual to guide doctors in the evaluation, diagnosis and treatment of their patients.

“Should you diagnose Alzheimer’s disease in asymptomatic persons? The answer is no,” Jack said.

The changes did not reassure skeptics.

Widera pointed out that under the revised plan, an unimpaired person who tests positive for an Alzheimer’s biomarker would not be considered “at risk” for the disease because — in the panel’s view — they already have it.

“They are redefining what it means to have Alzheimer’s,” he said. “You no longer need to have cognitive impairment to have this disease. You just need the positive blood test.”

They are redefining what it means to have Alzheimer’s.

— Dr. Eric Widera, a geriatrician at UC San Francisco

That could lead doctors to prescribe the new drugs to people without memory problems, Widera said.

Indeed, interest in testing for Alzheimer’s-related proteins exploded after the FDA controversially approved Aduhelm and Leqembi, which reduce amyloid levels in the brain.

The hypothesis is that finding amyloid early and removing it might avoid irreversible brain damage. But so far researchers have failed to demonstrate that a build-up of amyloid causes dementia — or that removing it alleviates symptoms.

The FDA went against the advice of its independent advisory committee and green-lighted Biogen’s Aduhelm in 2021 even though there was a lack of evidence that it reduced cognitive decline. A Congressional investigation later found that Biogen executives met with FDA officials — including Dr. Billy Dunn, head of the neuroscience office — dozens of times and inappropriately collaborated on a key regulatory document. Dunn did not respond to questions from The Times.

The FDA approved the second drug, Eisai’s Leqembi, in July after a study showed it could slow the progression of Alzheimer’s in people with mild cognitive impairment by less than half a point on an 18-point scale, a finding that some doctors doubt would be noticeable to patients or their families.

The agency requires both drugs to carry warnings that they can cause potentially fatal bleeding or swelling in the brain.

A closeup of a human brain affected by Alzheimer’s disease is on display at the Museum of Neuroanatomy at the University at Buffalo in Buffalo, N.Y.

(David Duprey / Associated Press)

The Alzheimer’s Assn. has been among the most vocal advocates for the two drugs, which each cost more than $26,000 a year. The group deployed hundreds of volunteers to lobby Congress and get Medicare to pay for the treatments.

While prescriptions of Leqembi are now taking off, doctors have hesitated to prescribe Aduhelm. Last month, Biogen said it planned to stop selling Aduhelm and instead focus on promoting Leqembi through its partnership with Eisai.

The Alzheimer’s Assn.’s plan to create a new class of symptom-free Alzheimer’s patients began taking shape more than a decade ago and was included in proposals to update diagnostic criteria for the disease in 2011 and 2018.

The association’s website says the idea came from a meeting of its Research Roundtable, a group that companies pay thousands of dollars to join. The roundtable meets twice a year, often at the luxury Park Hyatt Hotel in Washington, D.C. Current members include Biogen, Eisai, Lilly, Genentech, Prothena and 15 other companies. Selected academics and drug regulators from around the world are also invited to attend.

In its 2023 fiscal year, the Alzheimer’s Assn. received $4.9 million from pharmaceutical, biotech, diagnostic and clinical research companies — more than in any of the previous five years. The association said those corporate donations amount to just 1.3% of its total cash donations of $379 million that year.

Carrillo, the association’s chief science officer, told The Times in a statement that “no contribution from any organization impacts the Alzheimer’s Association decision-making, nor our positions.”

“We make our decision based on science, and the needs of our constituents,” she said.

The association spent $100 million on research in its 2023 fiscal year, including grants to some of the academic scientists on the panel or to the universities they work for. Many of those grants are aimed at creating new strategies for early diagnosis of people without memory complaints.

That message of early detection is echoed by pharmaceutical and testing companies. At a scientific conference in Boston in October, Dr. Mark Mintun, an Eli Lilly executive who is an advisor to the panel, said in a presentation that the company’s experimental medicine donanemab helped younger people and those with lower levels of tau more than it helped older people and those with higher levels of the protein.

“This gives us great urgency in thinking about how to diagnose and prepare patients for treatment,” Mintun told the audience, according to a report on the Alzforum news website.

Among the seven industry executives sitting on the Alzheimer’s Assn. panel are former FDA official Dunn, who is now on the board of Prothena, a company developing anti-amyloid drugs; Dr. Eric Siemers, chief medical officer of Acumen Pharmaceuticals, which is also working on anti-amyloid drugs; and Dr. Philip Scheltens, who heads a venture capital fund that invests in dementia drugs.

They are joined by Dr. Reisa Sperling, a Harvard neurology professor who has received research grants from Eisai and Lilly and consulting fees from 18 other companies, according to the panel’s disclosures.

Sperling has led studies investigating the value of treating people without memory problems. She said in 2013 that she could see a future where “we will treat everybody preemptively, in the same way we vaccinate.”

Other academic panel members include Charlotte Teunissen, a professor at Amsterdam University Medical Centers who conducts research for 25 companies, and Dr. Michael Rafii, a USC professor of clinical neurology, who disclosed work for 11 companies.

Both Teunissen and Rafii said their industry funding has no bearing on their judgment.

“I believe working with a diverse group of pharmaceutical and biotech companies, each with their own therapeutic approaches and strategies, can mitigate against a single company’s influence,” Rafii said.

Sperling agreed that corporate research funding did not affect her objectivity. “I want to figure out the truth,” she said.

But others are not convinced.

“This panel is dominated by those with financial ties to companies that will directly benefit” from a more expansive view of Alzheimer’s, said Widera of UCSF. “And there was no consideration about the potential downsides or risk to the number of people who are going to be now diagnosed” if its definition is adopted.

The proposal — initially dubbed “The National Institute of Aging–Alzheimer’s Association Revised Criteria for Diagnosing and Staging Alzheimer’s Disease” — has received international attention in part because it seemed to have the backing of one of the U.S. government’s premiere research centers.

The American Geriatrics Society and others said the proposal’s name implied that the NIA, which is part of the National Institutes of Health, was a full partner in the effort.

But Dr. Eliezer Masliah, director of the institute’s neuroscience division, said that while he and another NIA scientist attend panel meetings, they are not involved in its decisions. “We’re listening and recording and just keeping track of the process,” he said.

After The Times asked NIH officials about the NIA’s involvement, they said the institute’s name would be removed from the proposal’s title.

Even before the plan has been finalized, one company told investors it was poised to benefit.

In a November call with Wall Street analysts, Masoud Toloue, the chief executive at Quanterix, pointed out that the company’s blood test for tau — called p-Tau 217 — had been recommended by the panel for diagnosing the disease.

“We believe we’re in a strong position to capitalize on these opportunities,” Toloue said.

Science

Diablo Canyon clears last California permit hurdle to keep running

Central Coast Water authorities approved waste discharge permits for Diablo Canyon nuclear plant Thursday, making it nearly certain it will remain running through 2030, and potentially through 2045.

The Pacific Gas & Electric-owned plant was originally supposed to shut down in 2025, but lawmakers extended that deadline by five years in 2022, fearing power shortages if a plant that provides about 9 percent the state’s electricity were to shut off.

In December, Diablo Canyon received a key permit from the California Coastal Commission through an agreement that involved PG&E giving up about 12,000 acres of nearby land for conservation in exchange for the loss of marine life caused by the plant’s operations.

Today’s 6-0 vote by the Central Coast Regional Water Board approved PG&E’s plans to limit discharges of pollutants into the water and continue to run its “once-through cooling system.” The cooling technology flushes ocean water through the plant to absorb heat and discharges it, killing what the Coastal Commission estimated to be two billion fish each year.

The board also granted the plant a certification under the Clean Water Act, the last state regulatory hurdle the facility needed to clear before the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is allowed to renew its permit through 2045.

The new regional water board permit made several changes since the last one was issued in 1990. One was a first-time limit on the chemical tributyltin-10, a toxic, internationally-banned compound added to paint to prevent organisms from growing on ship hulls.

Additional changes stemmed from a 2025 Supreme Court ruling that said if pollutant permits like this one impose specific water quality requirements, they must also specify how to meet them.

The plant’s biggest water quality impact is the heated water it discharges into the ocean, and that part of the permit remains unchanged. Radioactive waste from the plant is regulated not by the state but by the NRC.

California state law only allows the plant to remain open to 2030, but some lawmakers and regulators have already expressed interest in another extension given growing electricity demand and the plant’s role in providing carbon-free power to the grid.

Some board members raised concerns about granting a certification that would allow the NRC to reauthorize the plant’s permits through 2045.

“There’s every reason to think the California entities responsible for making the decision about continuing operation, namely the California [Independent System Operator] and the Energy Commission, all of them are sort of leaning toward continuing to operate this facility,” said boardmember Dominic Roques. “I’d like us to be consistent with state law at least, and imply that we are consistent with ending operation at five years.”

Other board members noted that regulators could revisit the permits in five years or sooner if state and federal laws changes, and the board ultimately approved the permit.

Science

Deadly bird flu found in California elephant seals for the first time

The H5N1 bird flu virus that devastated South American elephant seal populations has been confirmed in seals at California’s Año Nuevo State Park, researchers from UC Davis and UC Santa Cruz announced Wednesday.

The virus has ravaged wild, commercial and domestic animals across the globe and was found last week in seven weaned pups. The confirmation came from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa.

“This is exceptionally rapid detection of an outbreak in free-ranging marine mammals,” said Professor Christine Johnson, director of the Institute for Pandemic Insights at UC Davis’ Weill School of Veterinary Medicine. “We have most likely identified the very first cases here because of coordinated teams that have been on high alert with active surveillance for this disease for some time.”

Since last week, when researchers began noticing neurological and respoiratory signs of the disease in some animals, 30 seals have died, said Roxanne Beltran, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. Twenty-nine were weaned pups and the other was an adult male. The team has so far confirmed the virus in only seven of the dead pups.

Infected animals often have tremors convulsions, seizures and muscle weakness, Johnson said.

Beltran said teams from UC Santa Cruz, UC Davis and California State Parks monitor the animals 260 days of the year, “including every day from December 15 to March 1” when the animals typically come ashore to breed, give birth and nurse.

The concerning behavior and deaths were first noticed Feb. 19.

“This is one of the most well-studied elephant seal colonies on the planet,” she said. “We know the seals so well that it’s very obvious to us when something is abnormal. And so my team was out that morning and we observed abnormal behaviors in seals and increased mortality that we had not seen the day before in those exact same locations. So we were very confident that we caught the beginning of this outbreak.”

In late 2022, the virus decimated southern elephant seal populations in South America and several sub-Antarctic Islands. At some colonies in Argentina, 97% of pups died, while on South Georgia Island, researchers reported a 47% decline in breeding females between 2022 and 2024. Researchers believe tens of thousands of animals died.

More than 30,000 sea lions in Peru and Chile died between 2022 and 2024. In Argentina, roughly 1,300 sea lions and fur seals perished.

At the time, researchers were not sure why northern Pacific populations were not infected, but suspected previous or milder strains of the virus conferred some immunity.

The virus is better known in the U.S. for sweeping through the nation’s dairy herds, where it infected dozens of dairy workers, millions of cows and thousands of wild, feral and domestic mammals. It’s also been found in wild birds and killed millions of commercial chickens, geese and ducks.

Two Americans have died from the virus since 2024, and 71 have been infected. The vast majority were dairy or commercial poultry workers. One death was that of a Louisiana man who had underlying conditions and was believed to have been exposed via backyard poultry or wild birds.

Scientists at UC Santa Cruz and UC Davis increased their surveillance of the elephant seals in Año Nuevo in recent years. The catastrophic effect of the disease prompted worry that it would spread to California elephant seals, said Beltran, whose lab leads UC Santa Cruz’s northern elephant seal research program at Año Nuevo.

Johnson, the UC Davis researcher, said the team has been working with stranding networks across the Pacific region for several years — sampling the tissue of birds, elephant seals and other marine mammals. They have not seen the virus in other California marine mammals. Two previous outbreaks of bird flu in U.S. marine mammals occurred in Maine in 2022 and Washington in 2023, affecting gray and harbor seals.

The virus in the animals has not yet been fully sequenced, so it’s unclear how the animals were exposed.

“We think the transmission is actually from dead and dying sea birds” living among the sea lions, Johnson said. “But we’ll certainly be investigating if there’s any mammal-to-mammal transmission.”

Genetic sequencing from southern elephant seal populations in Argentina suggested that version of the virus had acquired mutations that allowed it to pass between mammals.

The H5N1 virus was first detected in geese in China in 1996. Since then it has spread across the globe, reaching North America in 2021. The only continent where it has not been detected is Oceania.

Año Nuevo State Park, just north of Santa Cruz, is home to a colony of some 5,000 elephant seals during the winter breeding season. About 1,350 seals were on the beach when the outbreak began. Other large California colonies are located at Piedras Blancas and Point Reyes National Sea Shore. Most of those animals — roughly 900 — are weaned pups.

It’s “important to keep this in context. So far, avian influenza has affected only a small proportion of the weaned at this time, and there are still thousands of apparently healthy animals in the population,” Beltran said in a press conference.

Public access to the park has been closed and guided elephant seal tours canceled.

Health and wildlife officials urge beachgoers to keep a safe distance from wildlife and keep dogs leashed because the virus is contagious.

Science

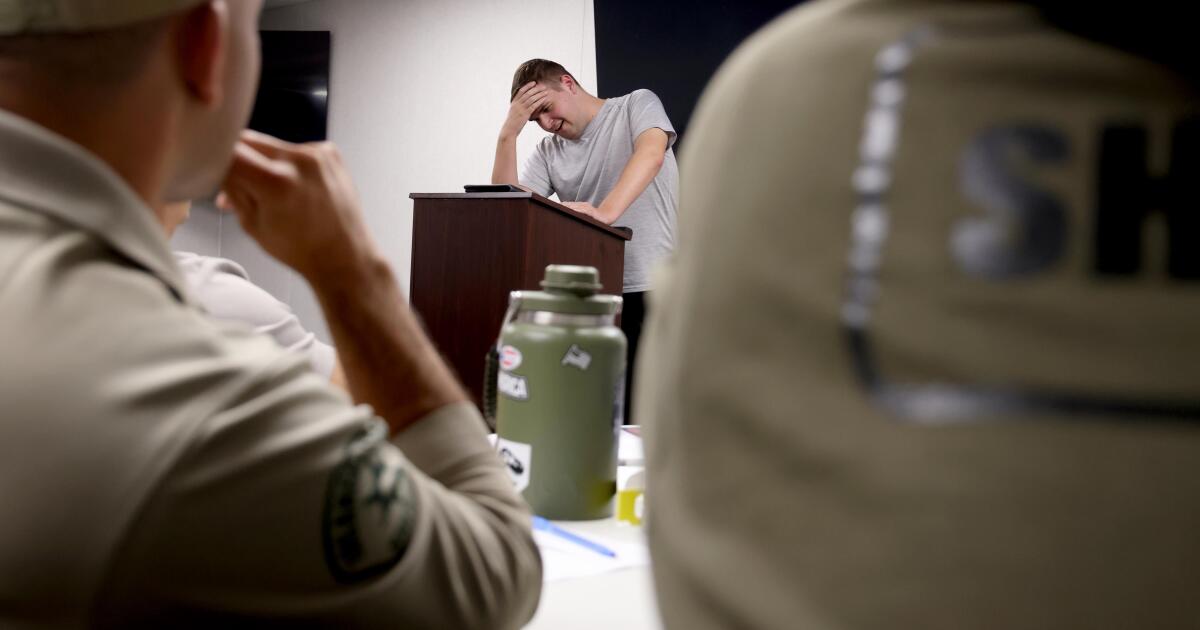

When slowing down can save a life: Training L.A. law enforcement to understand autism

Kate Movius moved among a roomful of Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies, passing out a pop trivia quiz and paper prism glasses.

She told them to put on the vision-distorting glasses, and to write with their nondominant hand. As they filled out the tests, Movius moved about the City of Industry classroom pounding abruptly on tables. Then came the cowbell. An aide flashed the overhead lights on and off at random. The goal was to help the deputies understand the feeling of sensory overwhelm, which many autistic people experience when incoming stimulation exceeds their capacity to process.

“So what can you do to assist somebody, or de-escalate somebody, or get information from someone who suffers from a sensory disorder?” Movius asked the rattled crowd afterward. “We can minimize sensory input. … That might be the difference between them being able to stay calm and them taking off.”

Movius, founder of the consultancy Autism Interaction Solutions, is one of a growing number of people around the U.S. working to teach law enforcement agencies to recognize autistic behaviors and ensure that encounters between neurodevelopmentally disabled people and law enforcement end safely.

She and City of Industry Mayor Cory Moss later passed out bags filled with tools donated by the city to aid interactions: a pair of noise-damping headphones to decrease auditory input, a whiteboard, a set of communication cards with words and images to point to, fidget toys to calm and distract.

“The thing about autistic behavior when it comes to law enforcement is a lot of it may look suspicious, and a lot of it may feel very disrespectful,” said Movius, who is also the parent of an autistic 25-year-old man. Responding officers, she said, “are not coming in thinking, ‘Could this be a developmentally disabled person?’ I would love for them to have that in the back of their minds.”

A sheriff’s deputy reads a pamphlet on autism during the training program.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Autism spectrum disorder is a developmental condition that manifests differently in nearly every person who has it. Symptoms cluster around difficulties in communication, social interaction and sensory processing.

An autistic person stopped by police might hold the officer’s gaze intensely or not look at them at all. They may repeat a phrase from a movie, repeat the officer’s question or temporarily lose their ability to speak. They might flee.

All are common involuntary responses for an autistic person in a stressful situation, which a sudden encounter with law enforcement almost invariably is. To someone unfamiliar with the condition, all could be mistaken for intoxication, defiance or guilt.

Autism rates in the U.S. have increased nearly fivefold since the Centers for Disease Control began tracking diagnoses in 2000, a rise experts attribute to broadening diagnostic criteria and better efforts to identify children who have the condition.

The CDC now estimates that 1 in 31 U.S. 8-year-olds is autistic. In California, the rate is closer to 1 in 22 children.

As diverse as the autistic population is, people across the spectrum are more likely to be stopped by law enforcement than neurotypical peers.

About 15% of all people in the U.S. ages 18 to 24 have been stopped by police at some point in their lives, according to federal data. While the government doesn’t track encounters for disabled people specifically, a separate study found that 20% of autistic people ages 21 to 25 have been stopped, often after a report or officer observation of a person behaving unusually.

Some of these encounters have ended in tragedy.

In 2021, Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies shot and permanently paralyzed a deaf autistic man after family members called 911 for help getting him to a hospital.

Isaias Cervantes, 25, had become distressed about a shopping trip and started pushing his mother, his family’s attorney said at the time. He resisted as two deputies attempted to handcuff him and one of the deputies shot him, according to a county report.

In 2024, Ryan Gainer’s family called 911 for support when the 15-year-old became agitated. Responding San Bernardino County sheriff‘s deputies shot and killed him outside his Apple Valley home.

Last year, police in Pocatello, Idaho, shot Victor Perez, 17, through a chain-link fence after the nonspeaking teenager did not heed their shouted commands. He died from his injuries in April.

Sheriff’s deputies take a trivia quiz using their non-writing hands, while wearing vision-distorting glasses, as Kate Movius, standing left, and Industry Mayor Cory Moss, right, ring cowbells. The idea was to help them understand the sensory overwhelm some autistic people experience.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

As early as 2001, the FBI published a bulletin on police officers’ need to adjust their approach when interacting with autistic people.

“Officers should not interpret an autistic individual’s failure to respond to orders or questions as a lack of cooperation or as a reason for increased force,” the bulletin stated. “They also need to recognize that individuals with autism often confess to crimes that they did not commit or may respond to the last choice in a sequence presented in a question.”

But a review of multiple studies last year by Chapman University researchers found that while up to 60% of officers have been on a call involving an autistic person, only 5% to 40% had received any training on autism.

In response, universities, nonprofits and private consultants across the U.S. have developed curricula for law enforcement on how to recognize autistic behaviors and adapt accordingly.

The primary goal, Movius told deputies at November’s training session, is to slow interactions down to the greatest extent possible. Many autistic people require additional time to process auditory input and verbal responses, particularly in unfamiliar circumstances.

If at all possible, Movius said, wait 20 seconds for a response after asking a question. It may feel unnaturally long, she acknowledged. But every additional question or instruction fired in that time — what’s your name? Did you hear me? Look at me. What’s your name? — just decreases the likelihood that a person struggling to process will be able to respond at all.

Moss’ son, Brayden, then 17, was one of several teenagers and young adults with autism who spoke or wrote statements to be read to the deputies. The diversity of their speech patterns and physical mannerisms showed the breadth of the spectrum. Some were fluently verbal, while others communicated through signs and notes.

“This population is so diverse. It is so complicated. But if there’s anything that we can show [deputies] in here that will make them stop and think, ‘Hey, what if this is autism?’ … it is saving lives,” Moss said.

Mayor Cory Moss, left, and Kate Movius hug at the end of the training program last November. Movius started Autism Interaction Solutions after her son was born with profound autism.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Some disability advocates cautioned that it takes more than isolated training sessions to ensure encounters end safely.

Judy Mark, co-founder and president of the nonprofit Disability Voices United, says she trained thousands of officers on safe autism interactions but stopped after Cervantes’ shooting. She now urges families concerned about an autistic child’s safety to call an ambulance rather than law enforcement.

“I have significant concern about these training sessions,” Mark said. “People get comfort from it, and the Sheriff’s Department can check the box.”

While not a panacea, supporters argue that a brief course is better than no preparation at all. Some years ago, Movius received a letter from a man whose profoundly autistic son slipped away as the family loaded their car at the beach. He opened the unlocked door of a police vehicle, climbed into the back and began to flail in distress.

Though surprised, the officer seated at the wheel de-escalated the situation and helped the young man find his family, the father wrote to Movius. He had just been to her training.

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making