Science

A total eclipse is more than a spectacle. So I'm on the road to see it — again

With the probable exception of glimpsing Earthrise out the window of Apollo 8, a total solar eclipse may be the best show in the universe accessible to human eyes.

I didn’t quite understand this seven years ago when I drove 900 miles all night and into morning from L.A. to Idaho the last time a total eclipse visited North America.

But what I saw then has set me on the road again, by plane and car to St. Louis, with plans to venture southeast for Monday’s eclipse.

The allure is not just the spectacle of this astronomical rarity. A partial solar eclipse, as will be visible Monday from Los Angeles and the rest of the contiguous United States — weather permitting — is a marvel not to be missed. But I am not traveling halfway across the country just to see a partial eclipse gone total.

I am going to watch the sun turn into a platypus.

At the instant the lunar disk slips entirely over the solar disk, the sun is abruptly transfigured into a foreign object. As if you looked at your watch and it suddenly turned into a flower.

Those lovely eclipse photos of a brilliant white halo (the solar corona, visible only during an eclipse) surrounding the deep black lunar sphere are poor preparation for the event. As I looked up from an Idaho Falls roadside lot in August 2017, at the moment of total eclipse the sun was no longer the sun.

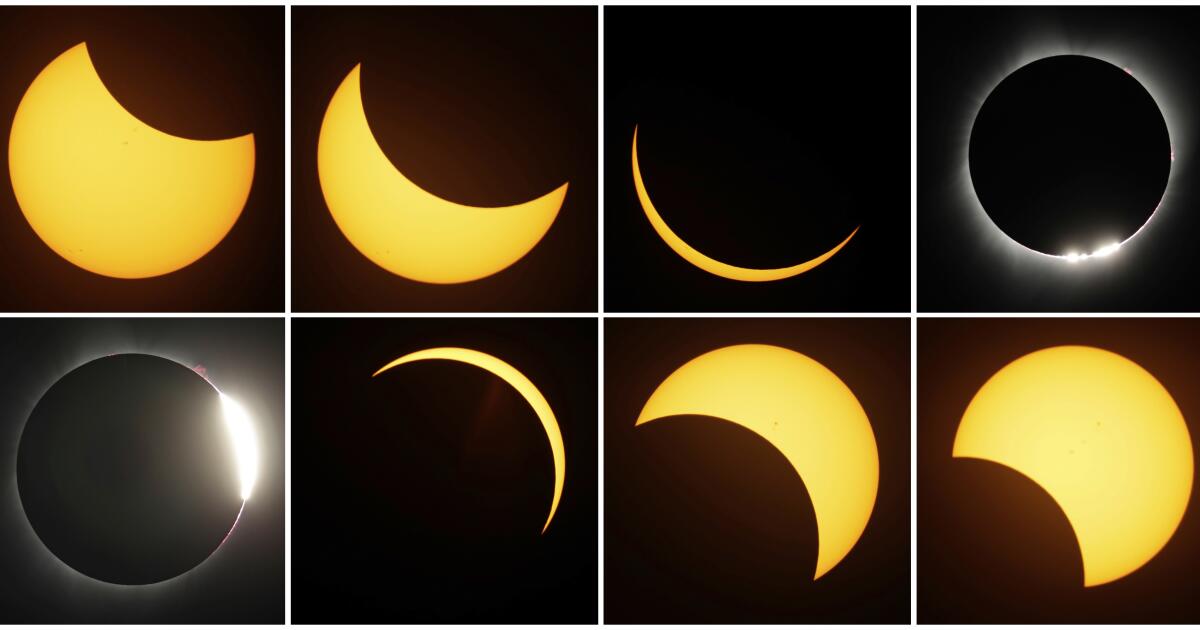

This combination of photos shows the progression of the eclipse of Aug. 21, 2017, near Redmond, Ore.

(Ted S. Warren / Associated Press)

I felt as I imagine the bemused European naturalists must have when, in 1799, they beheld for the first time a platypus specimen, a creature they found so peculiar they initially declared it an Australian hoax. What I saw above Idaho was neither fish nor fowl, and I could not quite convince myself it was real.

“In the sky was something that should not be there,” Annie Dillard wrote in her essay on seeing the moon obliterate the sun near Yakima, Wash., in 1979. In her view, this was not a good thing. “I pray you will never see anything more awful in the sky.”

In the sky was something that should not be there

— Annie Dillard, on the 1979 eclipse

When 38 years later I witnessed the next total solar eclipse viewable from the United States, I too was shaken, though in a very different way.

The moment of “totality,” as it’s called in astronomy lingo, issues a shock to the system, as if one were plunged into an ice cold pond. Day fades and then suddenly — snap! — flips to night, or twilight at least. Temperature falls, the wind rises. Stars and planets alight on their evening perches. Twilight too is total — 360 degrees: On any horizon can be seen the familiar orange glow we associate with sunrise or sunset.

I was literally breathless. I gasped to recover my lungs’ normal function. Voices around me exclaimed, with variations of “oh-my-God” or “holy” punctuated with swear words of choice.

In my usual job as a copy editor for this newspaper, I tend to cast a skeptical eye on a writer’s use of the word “ecstatic.” I can confirm that when it comes to watching a total eclipse, the word is warranted.

Though we moderns stand on the terra firma of scientific rigor — since at least the 1st century BC, astronomers have been able to predict eclipses roughly, and with ever-greater precision since Edmond Halley in the 18th century — we can appreciate how a total eclipse must’ve scared the devil out of the ancients.

Mythology is filled with apocalyptic visions associated with eclipses. They appear as ill omens in Shakespeare and, of course, the Bible. Milton summed it up in “Samson Agonistes”: “Oh dark, dark, dark, amid the blaze of noon, / Irrecoverably dark, total Eclipse / Without all hope of day!”

Christopher Columbus used his foreknowledge of a lunar eclipse to force the Arawak residents of present-day Jamaica to heel in fear in 1504.

(Frederic Lewis / Getty Images)

So terrified were the warring Lydians and Medes at the arrival of an eclipse in 585 BC, Herodotus tells us, they immediately made peace. Columbus used his foreknowledge of a lunar eclipse to force the Arawak residents of present-day Jamaica to heel in fear. As late as the 19th century, a solar eclipse over Virginia inspired Nat Turner to launch his violent uprising. The 1878 eclipse in the U.S. aroused fears of Armageddon, moving one man to kill his young son with an ax and slit his own throat. The acclaimed essay by Dillard, a fellow modern, is a doomscape of terror and death.

I find a total solar eclipse to be an affirmation of humanity, both as experience and as a triumph of knowledge over the glare of ignorance. Eclipses were once crucial in producing more accurate land and sea maps, and they inform solar science to this day. English astronomer Arthur Eddington’s eclipse expedition of 1919 proved Einstein’s theory of general relativity beyond a shadow of a doubt.

At the instant of totality, planetary motion as described by Newton and Kepler is not a matter only for scientists and our imaginations. It is something to be seen and felt by anyone in the right place at the right time. Our moon is orbiting us; the sphere on which we stand is also in motion, on its daily axis and annually lapping the sun. It is one thing to know and understand this; it is another to experience it.

Our everyday illusions are exposed as counterfeit: of a sky above, when in fact sky is all around us; of the sun rising and setting, when it does no such thing; of a moon waxing and waning, when it is continuously circling us with its same face forward. “We are an impossibility in an impossible universe,” author Ray Bradbury said.

And just what is this cosmic platypus, this something in the sky that should not be there? Similes abound.

A total eclipse of the sun is said to look like a black dahlia or a monochrome sunflower. Or a hole punched in the sky.

I prefer to think of it as a Louise Nevelson sculpture suspended above.

Many of Nevelson’s well-known works of the 1950s to 1970s were monochromatic black. Influenced by the space exploration of her time, the artist suggested celestial objects in her sculptures and chose titles featuring “night,” “sky,” “lunar,” “moon.” On at least one occasion, she took inspiration from astronaut Bill Anders’ “Earthrise” photo of 1968.

Her sculptures were, perhaps most of all, a meditation on the color black.

During a total eclipse, the sun’s blazing corona and “diamond ring” of light oozing outside the lunar disk just before and after totality are the main spectacle. But I was just as transfixed by the absolute blackness of the moon within. It is almost certainly the blackest black possible.

“I fell in love with black; it contained all color,” Nevelson once explained. “It wasn’t a negation of color. It was an acceptance. Because black encompasses all colors.” Black, for Nevelson, was “the total color. It means totality. It means: contain all.”

That is the lunar black I saw over Idaho Falls and which draws me now to Missouri. The title of a celebrated series of Nevelson works, “Sky Cathedral,” would do well as a name for nature’s occasional exhibition of lunar-solar art.

The 2024 eclipse arrives at a grim time in our history. We have witnessed the worst pandemic in a century. Gun violence at home and excruciating wars abroad seem impossibly intractable. Climate denial imperils our existence and a pernicious relativism our democracy. My profession and my newspaper, proudly committed to separating facts from fabrication, are at a crossroads of sustainability.

So a few minutes of astronomical truth seem all the more necessary for me to revisit at this time, though now with better preparation.

In 2017 I embarked on my all-night drive to see the eclipse out of last-minute inspiration. As an avid sky-watcher, I had an obvious interest. Not yet knowing what I was in for, though, I dawdled, thinking the journey too far and impractical, until I finally relented about 20 hours before totality over Idaho. I arrived with hours to spare under propitious skies.

I regretted my lack of planning on the way back, when I endured a traffic doomsday on Interstate 15 and could find no hotel vacancy along the route south before I finally gave up and slept in my car.

My eclipse preparations this time have been more considered and considerable, though complicated.

An early plan for an eclipse viewing in Rochester, N.Y., fell through. In the meantime, I have assembled a small library of eclipse books and magazines, including a road atlas that superimposes the 2024 path of totality onto a detailed map of the U.S., Mexico and Canada.

I considered joining the eclipse crowds in Carbondale, Ill., where a news report on Atlas Obscura said that old-time apocalyptic fever — also known as modern-day conspiracy theorist hokum — had taken hold.

Bob Baer of Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, co-chair of the Southern Illinois Eclipse 2017-2024 Steering Committee, will be leading a comprehensive monitoring effort to capture Monday’s solar eclipse moment by moment.

(Carlos Javier Ortiz / Getty Images)

Because Carbondale happened to be in the path of totality in 2017 and is so again in 2024, it seems many believed Monday’s eclipse encore would trigger a calamitous seismic event in town. This disturbing local opinion suggested to me an intriguing juxtaposition of setting for my notion of affirming the reality of our shared universe under the shadow of the moon.

The prime spot seemed to be southern Texas. Historical weather records indicate that the path through Texas had a much greater likelihood of cloud-free skies than farther northeast. And the duration of totality near the path’s center line was due to be almost 4½ minutes. As this eclipse moves northeast, its duration will get shorter, its path narrower.

Monday’s total eclipse will arrive on Mexico’s Pacific coast, climb through Texas and Arkansas, then cross the Midwest and New England before exiting over eastern Canada into the Atlantic.

(Associated Press)

In Idaho Falls, totality lasted about 1 minute and 40 seconds. Four and a half minutes over Texas? I could hardly fathom it. I made plans for San Antonio.

Until the actual meteorological forecast defied historical prediction. As eclipse day drew near, “weather permitting” turned more ominous. Less than a week out, the April 8 forecast for Texas — nearly the entire state, apparently — called for overcast skies all day, maybe even thunderstorms.

I studied my alternatives. Flights were still reasonable to Chicago, from where I could drive a few hours to reach several cities along the path: Indianapolis, Cleveland, even Buffalo. I also considered Mexico, but the forecast for the whole of its eclipse path, from Mazatlán to the border town of Piedras Negras, was likewise dire.

I added 16 cities to my phone’s weather app, from Mazatlán to Buffalo, which I monitored as the 8th drew near. Days before my planned departure, I booked accommodations in St. Louis, two hours from the center line.

The weather may yet conspire against me, and 3 or 4 minutes of totality will be lost under a ceiling of clouds. If so, I will see something I never have before. The midday gray blackening, then brightening, on account of a remote and veiled disk of sun and moon.

Astronaut Bill Anders snapped his “Earthrise” photo from the window of Apollo 8 on Dec. 24, 1968.

(NASA)

Either way, Bradbury advised, we are obliged to keep watch:

Why have we been put here? … There’s no use having a universe … there’s no use having a billion stars, there’s no use having a planet Earth if there isn’t someone here to see it. You are the audience. You are here to witness and celebrate. And you’ve got a lot to see and a lot to celebrate.

Science

Commentary: My toothache led to a painful discovery: The dental care system is full of cavities as you age

I had a nagging toothache recently, and it led to an even more painful revelation.

If you X-rayed the state of oral health care in the United States, particularly for people 65 and older, the picture would be full of cavities.

“It’s probably worse than you can even imagine,” said Elizabeth Mertz, a UC San Francisco professor and Healthforce Center researcher who studies barriers to dental care for seniors.

Mertz once referred to the snaggletoothed, gap-filled oral health care system — which isn’t really a system at all — as “a mess.”

But let me get back to my toothache, while I reach for some painkiller. It had been bothering me for a couple of weeks, so I went to see my dentist, hoping for the best and preparing for the worst, having had two extractions in less than two years.

Let’s make it a trifecta.

My dentist said a molar needed to be yanked because of a cellular breakdown called resorption, and a periodontist in his office recommended a bone graft and probably an implant. The whole process would take several months and cost roughly the price of a swell vacation.

I’m lucky to have a great dentist and dental coverage through my employer, but as anyone with a private plan knows, dental insurance can barely be called insurance. It’s fine for cleanings and basic preventive routines. But for more complicated and expensive procedures — which multiply as you age — you can be on the hook for half the cost, if you’re covered at all, with annual payout caps in the $1,500 range.

“The No. 1 reason for delayed dental care,” said Mertz, “is out-of-pocket costs.”

So I wondered if cost-wise, it would be better to dump my medical and dental coverage and switch to a Medicare plan that costs extra — Medicare Advantage — but includes dental care options. Almost in unison, my two dentists advised against that because Medicare supplemental plans can be so limited.

Sorting it all out can be confusing and time-consuming, and nobody warns you in advance that aging itself is a job, the benefits are lousy, and the specialty care you’ll need most — dental, vision, hearing and long-term care — are not covered in the basic package. It’s as if Medicare was designed by pranksters, and we’re paying the price now as the percentage of the 65-and-up population explodes.

So what are people supposed to do as they get older and their teeth get looser?

A retired friend told me that she and her husband don’t have dental insurance because it costs too much and covers too little, and it turns out they’re not alone. By some estimates, half of U.S. residents 65 and older have no dental insurance.

That’s actually not a bad option, said Mertz, given the cost of insurance premiums and co-pays, along with the caps. And even if you’ve got insurance, a lot of dentists don’t accept it because the reimbursements have stagnated as their costs have spiked.

But without insurance, a lot of people simply don’t go to the dentist until they have to, and that can be dangerous.

“Dental problems are very clearly associated with diabetes,” as well as heart problems and other health issues, said Paul Glassman, associate dean of the California Northstate University dentistry school.

There is one other option, and Mertz referred to it as dental tourism, saying that Mexico and Costa Rica are popular destinations for U.S. residents.

“You can get a week’s vacation and dental work and still come out ahead of what you’d be paying in the U.S.,” she said.

Tijuana dentist Dr. Oscar Ceballos told me that roughly 80% of his patients are from north of the border, and come from as far away as Florida, Wisconsin and Alaska. He has patients in their 80s and 90s who have been returning for years because in the U.S. their insurance was expensive, the coverage was limited and out-of-pocket expenses were unaffordable.

“For example, a dental implant in California is around $3,000-$5,000,” Ceballos said. At his office, depending on the specifics, the same service “is like $1,500 to $2,500.” The cost is lower because personnel, office rent and other overhead costs are cheaper than in the U.S., Ceballos said.

As we spoke by phone, Ceballos peeked into his waiting room and said three patients were from the U.S. He handed his cellphone to one of them, San Diegan John Lane, who said he’s been going south of the border for nine years.

“The primary reason is the quality of the care,” said Lane, who told me he refers to himself as 39, “with almost 40 years of additional” time on the clock.

Ceballos is “conscientious and he has facilities that are as clean and sterile and as medically up to date as anything you’d find in the U.S.,” said Lane, who had driven his wife down from San Diego for a new crown.

“The cost is 50% less than what it would be in the U.S.,” said Lane, and sometimes the savings is even greater than that.

Come this summer, Lane may be seeing even more Californians in Ceballos’ waiting room.

“Proposed funding cuts to the Medi-Cal Dental program would have devastating impacts on our state’s most vulnerable residents,” said dentist Robert Hanlon, president of the California Dental Assn.

Dental student Somkene Okwuego smiles after completing her work on patient Jimmy Stewart, 83, who receives affordable dental work at the Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC on the USC campus in Los Angeles on February 26, 2026.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Under Proposition 56’s tobacco tax in 2016, supplemental reimbursements to dentists have been in place, but those increases could be wiped out under a budget-cutting proposal. Only about 40% of the state’s dentists accept Medi-Cal payments as it is, and Hanlon told me a CDA survey indicates that half would stop accepting Medi-Cal patients and many others will accept fewer patients.

“It’s appalling that when the cost of providing healthcare is at an all-time high, the state is considering cutting program funding back to 1990s levels,” Hanlon said. “These cuts … will force patients to forgo or delay basic dental care, driving completely preventable emergencies into already overcrowded emergency departments.”

Somkene Okwuego, who as a child in South L.A. was occasionally a patient at USC’s Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry clinic, will graduate from the school in just a few months.

I first wrote about Okwuego three years ago, after she got an undergrad degree in gerontology, and she told me a few days ago that many of her dental patients are elderly and have Medi-Cal or no insurance at all. She has also worked at a Skid Row dental clinic, and plans after graduation to work at a clinic where dental care is free or discounted.

Okwuego said “fixing the smiles” of her patients is a privilege and boosts their self-image, which can help “when they’re trying to get jobs.” When I dropped by to see her Thursday, she was with 83-year-old patient Jimmy Stewart.

Stewart, an Army veteran, told me he had trouble getting dental care at the VA and had gone years without seeing a dentist before a friend recommended the Ostrow clinic. He said he’s had extractions and top-quality restorative care at USC, with the work covered by his Medi-Cal insurance.

I told Stewart there could be some Medi-Cal cuts in the works this summer.

“I’d be screwed,” he said.

Him and a lot of other people.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

Science

Diablo Canyon clears last California permit hurdle to keep running

Central Coast Water authorities approved waste discharge permits for Diablo Canyon nuclear plant Thursday, making it nearly certain it will remain running through 2030, and potentially through 2045.

The Pacific Gas & Electric-owned plant was originally supposed to shut down in 2025, but lawmakers extended that deadline by five years in 2022, fearing power shortages if a plant that provides about 9 percent the state’s electricity were to shut off.

In December, Diablo Canyon received a key permit from the California Coastal Commission through an agreement that involved PG&E giving up about 12,000 acres of nearby land for conservation in exchange for the loss of marine life caused by the plant’s operations.

Today’s 6-0 vote by the Central Coast Regional Water Board approved PG&E’s plans to limit discharges of pollutants into the water and continue to run its “once-through cooling system.” The cooling technology flushes ocean water through the plant to absorb heat and discharges it, killing what the Coastal Commission estimated to be two billion fish each year.

The board also granted the plant a certification under the Clean Water Act, the last state regulatory hurdle the facility needed to clear before the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is allowed to renew its permit through 2045.

The new regional water board permit made several changes since the last one was issued in 1990. One was a first-time limit on the chemical tributyltin-10, a toxic, internationally-banned compound added to paint to prevent organisms from growing on ship hulls.

Additional changes stemmed from a 2025 Supreme Court ruling that said if pollutant permits like this one impose specific water quality requirements, they must also specify how to meet them.

The plant’s biggest water quality impact is the heated water it discharges into the ocean, and that part of the permit remains unchanged. Radioactive waste from the plant is regulated not by the state but by the NRC.

California state law only allows the plant to remain open to 2030, but some lawmakers and regulators have already expressed interest in another extension given growing electricity demand and the plant’s role in providing carbon-free power to the grid.

Some board members raised concerns about granting a certification that would allow the NRC to reauthorize the plant’s permits through 2045.

“There’s every reason to think the California entities responsible for making the decision about continuing operation, namely the California [Independent System Operator] and the Energy Commission, all of them are sort of leaning toward continuing to operate this facility,” said boardmember Dominic Roques. “I’d like us to be consistent with state law at least, and imply that we are consistent with ending operation at five years.”

Other board members noted that regulators could revisit the permits in five years or sooner if state and federal laws changes, and the board ultimately approved the permit.

Science

Deadly bird flu found in California elephant seals for the first time

The H5N1 bird flu virus that devastated South American elephant seal populations has been confirmed in seals at California’s Año Nuevo State Park, researchers from UC Davis and UC Santa Cruz announced Wednesday.

The virus has ravaged wild, commercial and domestic animals across the globe and was found last week in seven weaned pups. The confirmation came from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa.

“This is exceptionally rapid detection of an outbreak in free-ranging marine mammals,” said Professor Christine Johnson, director of the Institute for Pandemic Insights at UC Davis’ Weill School of Veterinary Medicine. “We have most likely identified the very first cases here because of coordinated teams that have been on high alert with active surveillance for this disease for some time.”

Since last week, when researchers began noticing neurological and respoiratory signs of the disease in some animals, 30 seals have died, said Roxanne Beltran, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. Twenty-nine were weaned pups and the other was an adult male. The team has so far confirmed the virus in only seven of the dead pups.

Infected animals often have tremors convulsions, seizures and muscle weakness, Johnson said.

Beltran said teams from UC Santa Cruz, UC Davis and California State Parks monitor the animals 260 days of the year, “including every day from December 15 to March 1” when the animals typically come ashore to breed, give birth and nurse.

The concerning behavior and deaths were first noticed Feb. 19.

“This is one of the most well-studied elephant seal colonies on the planet,” she said. “We know the seals so well that it’s very obvious to us when something is abnormal. And so my team was out that morning and we observed abnormal behaviors in seals and increased mortality that we had not seen the day before in those exact same locations. So we were very confident that we caught the beginning of this outbreak.”

In late 2022, the virus decimated southern elephant seal populations in South America and several sub-Antarctic Islands. At some colonies in Argentina, 97% of pups died, while on South Georgia Island, researchers reported a 47% decline in breeding females between 2022 and 2024. Researchers believe tens of thousands of animals died.

More than 30,000 sea lions in Peru and Chile died between 2022 and 2024. In Argentina, roughly 1,300 sea lions and fur seals perished.

At the time, researchers were not sure why northern Pacific populations were not infected, but suspected previous or milder strains of the virus conferred some immunity.

The virus is better known in the U.S. for sweeping through the nation’s dairy herds, where it infected dozens of dairy workers, millions of cows and thousands of wild, feral and domestic mammals. It’s also been found in wild birds and killed millions of commercial chickens, geese and ducks.

Two Americans have died from the virus since 2024, and 71 have been infected. The vast majority were dairy or commercial poultry workers. One death was that of a Louisiana man who had underlying conditions and was believed to have been exposed via backyard poultry or wild birds.

Scientists at UC Santa Cruz and UC Davis increased their surveillance of the elephant seals in Año Nuevo in recent years. The catastrophic effect of the disease prompted worry that it would spread to California elephant seals, said Beltran, whose lab leads UC Santa Cruz’s northern elephant seal research program at Año Nuevo.

Johnson, the UC Davis researcher, said the team has been working with stranding networks across the Pacific region for several years — sampling the tissue of birds, elephant seals and other marine mammals. They have not seen the virus in other California marine mammals. Two previous outbreaks of bird flu in U.S. marine mammals occurred in Maine in 2022 and Washington in 2023, affecting gray and harbor seals.

The virus in the animals has not yet been fully sequenced, so it’s unclear how the animals were exposed.

“We think the transmission is actually from dead and dying sea birds” living among the sea lions, Johnson said. “But we’ll certainly be investigating if there’s any mammal-to-mammal transmission.”

Genetic sequencing from southern elephant seal populations in Argentina suggested that version of the virus had acquired mutations that allowed it to pass between mammals.

The H5N1 virus was first detected in geese in China in 1996. Since then it has spread across the globe, reaching North America in 2021. The only continent where it has not been detected is Oceania.

Año Nuevo State Park, just north of Santa Cruz, is home to a colony of some 5,000 elephant seals during the winter breeding season. About 1,350 seals were on the beach when the outbreak began. Other large California colonies are located at Piedras Blancas and Point Reyes National Sea Shore. Most of those animals — roughly 900 — are weaned pups.

It’s “important to keep this in context. So far, avian influenza has affected only a small proportion of the weaned at this time, and there are still thousands of apparently healthy animals in the population,” Beltran said in a press conference.

Public access to the park has been closed and guided elephant seal tours canceled.

Health and wildlife officials urge beachgoers to keep a safe distance from wildlife and keep dogs leashed because the virus is contagious.

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts5 days ago

Massachusetts5 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO5 days ago

Denver, CO5 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWorld reacts as US top court limits Trump’s tariff powers