Science

A Powerful Climate Solution Just Below the Ocean’s Surface

They can bolster the coastlines, break the force of hurtling waves, provide housing for fish, shellfish, and migrating birds, clean the water, store as much as 5 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide, and pump oxygen into the ocean, in part making it possible for life on Earth as we know it.

These miracle machines are not the latest shiny tech invention. Rather, they are one of nature’s earliest floral creations: seagrasses. Anchored on the shorelines of every continent except Antarctica, these plants (and they are plants, not algae, that sprout, flower, fruit and go to seed) are one of the most powerful but unheralded climate solutions that already exist on the planet.

Restoring seagrass is one tool that coastal communities can use to address climate change, both by capturing emissions and mitigating their effects, which is among the topics being discussed as leaders in business, science, culture and policy gather on Thursday and Friday in Busan, South Korea, for a New York Times conference, A New Climate.

Around the world, scientists, nongovernmental organizations and volunteers are working to restore seagrass meadows, if not to their original glory, then to something far more expansive and majestic than the barren, muddy bottoms left behind when they are damaged or destroyed.

In Virginia, parts of Britain and Western Australia, among other places, with the helping hands of committed researchers and citizen scientists alike, seagrass meadows are coming back. They’re bringing with them clearer waters, stabler shores, and animals and other organisms that used to thrive there. And yet, seagrass doesn’t get the attention it deserves, its partisans say.

It’s impossible to know exactly how much seagrass has been lost, because scientists don’t know how much there was to begin with.

Only about 16 percent of global coastal ecosystems are considered intact, and seagrasses are among the hardest hit. It’s estimated that a third of seagrass around the world has disappeared in the last few decades, according to Matthew Long, an associate scientist in marine chemistry and geochemistry at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “Globally, a soccer field of seagrass is lost every 30 minutes,” Dr. Long said, “and we lose about 5 to 10 percent at an accelerated rate every single year.”

“Seagrasses are adversely affected by global stressors: deoxygenation, ocean acidification and warming temperatures,” Dr. Long said. But local stressors also have played a role in their withering, mainly in the form of nutrient pollution, largely from agricultural runoff and wastewater, and subsequent algal blooms and die-offs, which first choke out other plants like seagrass (a process called eutrophication) and then, as they decompose, take up all the oxygen in the water (hypoxia).

While the effects of climate change and growing human impacts have accelerated seagrass loss in the last few decades, it’s not a new story.

On the Eastern Shore of Virginia, a strong storm in August 1933 that followed a wasting disease and overharvesting of bay scallops, wiped out what remained of once vast eelgrass meadows. (Eelgrass is a type of seagrass.) For decades, there was no eelgrass on the shore’s ocean side, said Bo Lusk, a scientist with the Nature Conservancy’s Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve, though some remained on the part of the coast lapped by the Chesapeake Bay.

Dr. Lusk, who grew up in the region, heard stories as a child of lush green carpets of eelgrass from his grandmother, who remembered that the shores teemed with life — until they didn’t. But then, in 1997, someone reported seeing some patches of eelgrass on the shore’s oceanside, likely from seeds that happened to drift south from Maryland and settled in a hospitable neighborhood in Virginia.

After several years of experiments, Robert J. Orth, a scientist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, devised a highly successful method of restoring seagrass, similar to methods used around the world: In the spring, scientists and hundreds of volunteers collect seeds, which they count and process over the summer and plant in the sediment in the fall.

Since 2003, when the restoration effort in the Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve began, scientists and others have planted around 600 acres of seeds, and seagrass now covers 10,000 acres, according to Dr. Lusk. Later this year, the Nature Conservancy is hoping to sell the first validated blue carbon credits for seagrass, based on this restoration effort, said Jill Bieri, the director of the reserve.

However, the success of the Virginia project has been somewhat difficult to recreate around the world. “You can’t do this just anywhere,” Dr. Lusk said. “If the Nature Conservancy hadn’t started this land protection work 50 years ago, buying up parts of the coast to preserve it, the odds are we wouldn’t have the water quality we have now, and this wouldn’t have been so successful.”

Seagrass restoration will take decades of commitment, Dr. Lusk said. Richard Unsworth, an associate bioscience professor at Swansea University in Wales and the founder and chief scientific officer of Project Seagrass, a British NGO that works on seagrass restoration, said that an important part of the work was the long-term promise made to the whole ecosystem — the seagrass meadows, but also the people in the community.

“The actions of fishermen, the views of boat owners, the problems of water quality — they can all be part of a complex social-cultural situation, and in the long term it will be an amazing success, but it’s a slow process, not some silver bullet where you plant something and then you’ve saved it,” Dr. Unsworth said.

Community engagement has been a necessary part for seagrass success since it takes a lot of work to collect and plant millions of seeds. For Project Seagrass, that has also meant the development of a website and app, Seagrass Spotter, which allows users to upload photos of seagrass in the wild (which is then verified by scientists), to help researchers fully map the extent and types of seagrasses around the world, since mapping of seagrass globally is rather patchy.

But one place it’s well mapped is Shark Bay, a remote section of the coast in Western Australia, where seagrass from 10 different meadows was discovered to be actually just one plant, possibly the biggest in the world.

There, seagrass has been growing and accumulating carbon in its plant matter, but also in the sediment, for more than 3,000 years, said Elizabeth Sinclair, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Western Australia.

But during an extreme marine heat wave from 2010 to 2011, about a third of the seagrass canopy (what is visible above the sand) died, releasing as much as nine million tons of carbon, according to one estimate.

Over the last decade or so, Dr. Sinclair and her colleagues have been studying the recovery of the seagrass — the places where it’s come back naturally and where it likely never will, without some assistance from scientists as well as the Malgana people, Indigenous Australians who work as rangers.

Despite warming temperatures and changing ocean chemistry, which make complete restoration impossible, it’s still work worth doing, said Dr. Lusk, whether it’s on the crooked waterways of the Virginia coast, the rocky shores of Wales, or the sweeping, endless bays of Western Australia.

“There are so many logical reasons we should do this,” Dr. Lusk said. “The carbon storage is great, shoreline protection, all of this other stuff is great, and you can know that in your head but until you get in the water and spend some time really within this system, you don’t have the emotional connection.

“I would keep doing this if there was no carbon stored. It just feels right to be out there.”

Science

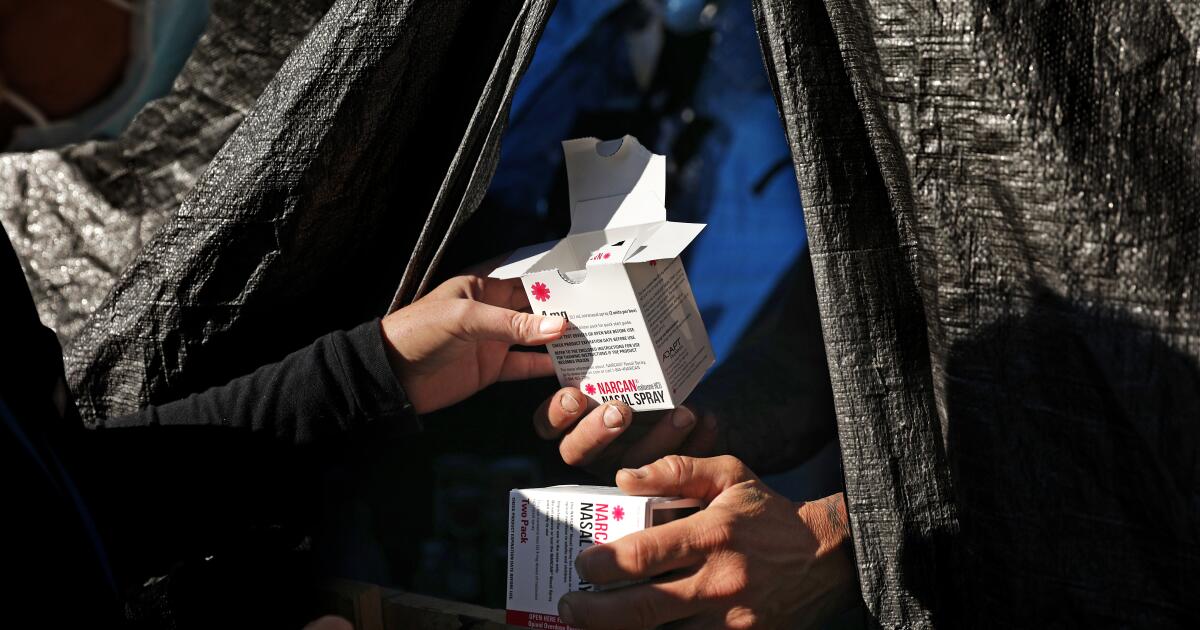

Deadly overdoses stopped surging among L.A. County homeless people. Narcan could be why

Year after year, Los Angeles County has seen devastating losses on its streets, as homeless people bedding down in tents, under tarps and on sidewalks have lost their lives to drug overdoses at soaring rates.

Now a newly released report shows the death rate from overdoses stopped rising among unhoused people in the county in 2022 — the same year L.A. County was stepping up its efforts to save lives.

Public health officials welcomed the news as a glint of hope, but cautioned it is too soon to say if the numbers are headed for a lasting downturn. They pointed to a county push to dramatically ramp up the distribution of naloxone — a medicine that bystanders can use to stop opioid overdoses — as a likely factor.

In their report, county officials touted a “near doubling” that year in the reported number of overdoses that were thwarted with naloxone, based on figures provided by a county program. The lifesaving medicine is commonly sold as a nasal spray under the brand name Narcan.

Two years ago in North Hollywood, Manny Placeres told The Times he had revived people seven times using Narcan that had been provided to him by a county team, honing his technique with time.

“As they’re knocking on heaven’s door, I pull them back,” Placeres said.

Manny Placeres, who has administered naloxone many times to reverse opioid overdoses on the streets, embraces Leimer in 2022.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

The L.A. County Department of Health Services has handed out Narcan at homeless encampments, given it to community groups and county agencies and set up vending machines to dispense it for free to people leaving county jails.

As of February, the health services department said it had distributed more than 600,000 doses of naloxone since launching its initiative, resulting in more than 25,000 overdoses being stopped. Community groups and syringe programs have bolstered such efforts by handing out their own supplies of free naloxone provided by the state.

Dr. Gary Tsai, director of the public health department’s substance abuse prevention and control bureau, said that after years of alarming increases, “it is encouraging to see a slowing of this leading cause of death for people experiencing homelessness.”

“Efforts to increase access to naloxone and overdose prevention services have undoubtedly helped to bend this curve and provide a blueprint for reducing drug-related fatalities in this very high-risk population,” he said in a statement.

County officials said such efforts had also helped stabilize the death rate for homeless people overall after years of disturbing growth. As deadly overdoses stopped surging and COVID-19 deaths plunged, the overall mortality rate among unhoused people in L.A. County began to level off, the report found.

But homeless people remained far more likely than other county residents to die in a range of ways, including overdoses, traffic collisions, heart disease and homicide.

Their death rate overall was nearly four times higher than that of the broader population — a gap that has widened over time, public health officials found. And although it may have finally hit a plateau, the mortality rate for homeless people in L.A. County was still 60% higher than it had been three years earlier.

“This report highlights the continued need for concerted efforts to reduce the disproportionate burden of mortality among this vulnerable population,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said in a statement.

The county report also pointed out some alarming variations in the overall trends in L.A. County: For Black people who were unhoused, for instance, the rate of overdose deaths continued to rise significantly in 2022.

The rate of fatal overdoses also kept rising among homeless people in their 20s and 40s, the report found. That was offset by dropping rates among older people, but the report raised a grim possibility: After so many deadly years, “there may now be fewer surviving fentanyl and other opioid users over 50.”

Narcan can stop overdoses from opioids such as fentanyl, a powerful synthetic drug that has been involved in a rising share of overdose deaths among homeless people in L.A. County.

But fentanyl has not been the only threat: Roughly two-thirds of deadly overdoses among unhoused people involved more than one drug. Among the most commonly mingled were fentanyl and methamphetamine, a combination involved in nearly half of overdose deaths among homeless people in the county in 2022, according to the new report.

L.A. County public health officials called for a number of steps to bring down deaths among unhoused people, including expanding housing options so that people who use drugs will not lose their housing as a result; handing out more naloxone and test strips that detect fentanyl; and expanding preventative care for people who are homeless.

Science

RFK Jr. says he had a dead worm in his brain. What are these parasites and how common are they?

Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has made various claims about his health over the years, but the most shocking came Wednesday when it was revealed that Kennedy once insisted that a worm ate a portion of his brain over a decade ago.

Kennedy’s assertion, which was reported by the New York Times, was made during divorce proceedings from his second wife, Mary Richardson Kennedy, and was intended to support his claim that health issues had reduced his earning potential.

Kennedy reportedly disclosed the ailment during a court deposition, saying that in 2010 he was experiencing memory loss and severe mental fogginess. He said he consulted with several neurologists who examined brain scans and suspected he had a brain tumor, and he was scheduled to undergo surgery.

But then a doctor at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital told Kennedy he believed the scans revealed the remnants of a dead parasite.

The abnormality in his scans “was caused by a worm that got into my brain and ate a portion of it and then died,” the article reported Kennedy as saying in the 2012 deposition.

No medical proof has been offered to back up the candidate’s claims, but the issue has prompted widespread conversation about the existence of brain worms, as well as the candidate’s fitness for office.

Kennedy addressed the issue in a tongue-and-cheek post on X on Wednesday saying that he could “eat 5 more brain worms and still beat President Trump and President Biden in a debate.” He added in another post, “I feel confident of the result even with a six-worm handicap.”

There are several parasites that can do damage in the human brain, but the most common in the Americas is the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium. In the intestines, the worm can grow to 2 to 7 meters in length. Though its eggs can migrate from the intestines to tissues throughout the body, in all other organs the larvae dies before reaching maturity.

A photomicrograph of the parasitic pork tapeworm Taenia solium.

(Dr. Mae Melvin / Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Multiple medical experts told The Times that the condition Kennedy described sounds like neurocysticercosis, a parasitic infection caused by the larval form of the pork tapeworm. Those doctors have not treated Kennedy and were speaking generally.

Depending on where the parasite lodges itself in or around the brain, the patient could either be entirely asymptomatic or experience headaches and seizures. Memory loss and cognitive problems of the kind Kennedy described in his deposition would be rare, said Dr. Edward Jones-Lopez, an infectious-disease specialist with Keck Medicine of USC.

“It would be unusual for the parasite to cause memory loss just as an isolated symptom,” he said.

Kennedy’s description of the worm dying after it “ate a portion” of his brain is also a “misnomer” when speaking about neurocysticercosis, Jones-Lopez said. The parasite dies before maturing into an animal capable of eating anything.

The tapeworm’s eggs are found in the feces of an infected person, and they can spread to other hosts who consume food or water contaminated by the feces. If someone touches a contaminated surface and then puts their fingers in their mouth without washing their hands, they can ingest the eggs as well.

Once swallowed, the eggs find their way into skeletal muscles or other tissues, where they form cysts and cause the disease known as cysticercosis.

“In the brain it is actually larvae (not the mature worm itself) that forms cysts, which when surgeons excise and give to us pathologists, is often dead,” wrote Dr. William Yong, a pathologist specializing in neuropathology at UC Irvine. “They only form adult tapeworms in the intestines. Anywhere else in the body they form these larval cysts that ultimately die, degenerate and calcify.”

T. solium cysts can also enter the digestive system in contaminated pork that is raw or undercooked, causing a condition called taeniasis. The CDC estimates there are probably fewer than 1,000 cases a year, but it’s difficult to know for sure because infections typically result in nothing worse than mild digestive problems, such as abdominal pain or an upset stomach.

If the cysts find a home in the small intestine, they can develop into adult tapeworms in about two months’ time. Their eggs could then spread and cause neurocysticercosis.

Calcified evidence of past infections has been turning up on the brain scans of patients who’ve had imaging taken for other reasons, leading doctors to conclude that most cases of neurocysticercosis are either asymptomatic or produce only mild symptoms. A single patient could have hundreds of these calcifications in their brain, said Dr. Diana Vargas, a neurologist and neuroimmunologist at the Emory University School of Medicine.

The parasite is typically seen in underdeveloped countries where pigs come in contact with human feces, said Dr. Charles Bailey, the medical director for infection prevention at Providence St. Joseph and Providence Mission hospitals.

“It can go from the GI tract and has a propensity to migrate into the brain,” Bailey said. “It can be asymptomatic until the parasite dies. Usually when it dies it triggers some local inflammatory response which causes swelling in that particular area that can lead to symptoms.”

The parasite is endemic in Central and South America, as well as some areas of Asia and Africa, Vargas said. It isn’t frequently seen in the United States, but there are still hundreds of hospitalizations per year, she said.

Bailey said in his four-decade career he’s seen 10 to 12 cases, mostly from people who have lived in Latin America.

“Most of the cases I’ve seen have not been in travelers. They’re people who have lived in that part of the world most or all of their life and for whom high-quality or fully cooked meat might not have been consistently available,” Bailey said. “It’s not something typical tourists should be concerned about.”

Kennedy told the New York Times that doctors told him the cyst they saw on his scan contained the remains of a parasite. He was unsure where he might have contracted it, but suspected it could have been during a trip he took to South Asia. It did not require any treatment, he said.

Bailey said there’s no need to remove the parasite surgically unless it’s located in an area of the brain where it’s causing problems. If it’s discovered before it dies, it can be treated with oral anti-parasitic medications, usually along with steroids to control swelling and inflammation that could become life-threatening.

It can take anywhere from several months to up to four years for symptoms to develop, Vargas said.

Other types of parasites that can lodge in the brain include schistosoma, a flatworm that burrows through the skin but doesn’t form the signature cyst that neurocysticercosis does, or echinococcus, which can infect the brain but far more typically attacks the liver, Jones-Lopez said.

Compared to T. solium, the other parasites “are so extremely rare,” Vargas said.

The presidential candidate says that over the years he’s suffered from atrial fibrillation — the most common type of heartbeat abnormality — mercury poisoning, hepatitis C from intravenous drug use in his youth and spasmodic dysphonia, a neurological disorder that causes his vocal cords to squeeze too close together.

Kennedy’s campaign press secretary Stefanie Spear said in a statement to The Times that Kennedy traveled extensively in Africa, South America and Asia doing environmental advocacy work and “in one of those locations contracted a parasite.”

“The issue was resolved more than 10 years ago, and he is in robust physical and mental health,” she said. “Questioning Mr. Kennedy’s health is a hilarious suggestion, given his competition.”

Kennedy, who is running to represent the American Independent Party, has been criticized for his extreme views and disinformation about vaccines.

In a podcast in 2021, Kennedy advised parents to “resist” the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines on vaccinating children. For years he has spread falsehoods about the effectiveness of vaccines and during a speech in 2022 said COVID-19 restrictions were something a totalitarian state would do, likening them to conditions in Nazi Germany.

Times staff writer Faith E. Pinho contributed to this report.

Science

Q&A: Parent burnout is real. Here's what you can do about it

It’s been several years since kids returned to their classrooms and workers went back to their offices. We dine indoors at restaurants and don’t hesitate to board a plane for a family trip.

COVID-19 isn’t disrupting our lives like it did in the days of lockdowns, social distancing and mandatory masking. So why are so many parents still struggling like it’s the height of the pandemic?

A report released Wednesday by researchers at the Ohio State University College of Nursing sums it up in two words: parental burnout.

“When the pressures of parenting lead to chronic stress and exhaustion that overwhelm a parent’s ability to cope and function, it is called parental burnout,” the report explains. This condition leaves moms and dads “feeling physically, mentally and emotionally exhausted, as well as often detached from their children.”

In a survey of 722 working parents conducted in June and July 2023, 57% reported symptoms indicative of this modern-day malady. That’s only a small improvement from the early months of 2021, when 66% of parents surveyed were described as burned out.

Report authors Kate Gawlik, a family nurse practitioner, and Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk, the university’s vice president of health promotion and its chief wellness officer, found that people struggling with parental burnout were straining to live up to unrealistic expectations. They felt judged by family and friends if they hadn’t steered their children onto the honor roll and an all-star sports team while planning a picturesque vacation and keeping their homes neat and tidy.

Bernadette Melnyk, left, and Kate Gawlik led a study that reveals how expectations to be the perfect parent contribute to burnout, stress, anxiety and depression among working parents.

(Ohio State University)

Those are the wrong goals, Gawlik and Melnyk said.

The survey found that the more extracurricular activities a child was involved in, the more likely he or she was to have trouble with concentration, get into fights with other kids, have low self-esteem and exhibit other behaviors that can lead to poor mental health.

However, those risk factors became less likely when children had more time for unstructured play and spent more quality time with their parents.

Not only is there no such thing as a perfect parent, but also, the more you try to be one, the more your efforts will backfire, Gawlik and Melnyk said. They spoke with The Times about what they’ve learned about parental burnout and how to overcome it.

What prompted you to study parental burnout?

Kate Gawlik: We really got interested in this idea of parental burnout during the pandemic. When it started, I had four children, and my oldest was in second grade. I was trying to work and be a parent and home-school and everything. I just had this constant feeling of having to do everything all the time.

I had heard the term “burnout,” but I never really related it to parenting. One day I heard the term “parental burnout” and I was like, that’s what I’m feeling. It’s not like depression, it’s not like anxiety. It’s this very focused burned-out feeling related to being a parent and having to do everything.

We’re in a much better place than we were back then. Does that mean parental burnout is better too?

Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk: People assumed that once the pandemic was over, things would just automatically improve. Our current study shows that’s really not the case. People didn’t just bounce back like a lot of people thought they would.

Gawlik: That’s why we wanted to study this again now. We don’t have the same stressors we had before. We wanted to look at what the stressors are now.

And what are they?

Gawlik: I feel like parents now are trying to make up for everything they lost, or felt they lost, during the pandemic.

We have really latched onto this culture of achievement. I see that and I feel that every day. Parents feel this continual pressure to keep up with everybody else. If their kids aren’t in honors classes, they need to get them tutoring so that they are. If they’re not the best at sports, they need to be putting them in even more practices.

It’s this continual cycle of more, more, more, more. How can you not feel burned out?

It’s this continual cycle of more more more more. How can you not feel burned out?

— Kate Gawlik

Melnyk: If a parent feels they’re a good parent, there’s not as much burnout and mental health issues. But if they aren’t feeling good about their parenting, there’s more burnout, more depression, and the kids have more issues. So the self-judgment piece is really key.

What makes someone prone to parental burnout?

Gawlik: Social media is very powerful, and very parent-shaming. A parent can look at social media and be like, “They look like they’re doing everything and they’re so happy and their house doesn’t seem chaotic at all. What’s wrong with mine?”

Melnyk: This whole “perfect parent” image that so many people strive for — it’s really important that parents know there’s no such thing.

Were you surprised to find that parental burnout was still so prevalent?

Melnyk: It was right about where we expected it to be. The pandemic didn’t resolve and then everybody gets back to normal. It takes time.

Were there other findings that did surprise you?

Gawlik: One of the things that I think was so striking was the relationship between child mental health and the number of extracurricular activities that children participate in. This is a great example where maybe as a parent you’re like, “OK, you can get back into sports, you can do everything.” But it’s almost to the detriment because we know that kids need time just to play.

Kids’ work is to play, and they’re not getting to do that. We’re robbing them of those opportunities because of all this structure. It’s all good intentions — we’re doing it to help our children — but the results of our study show that’s not where we need to be putting our time and focus.

Does burnout at work contribute to burnout at home?

Gawlik: When you’re with your kids, you’re always thinking about the things you need to get done at work. And then when you’re working, you’re always thinking about how you need to help your children. So you’re constantly in this state of turmoil, where you’re feeling this tug from both areas.

Melnyk: Honestly, in all likelihood, if you’re a working parent with children — especially if they have mental health needs — you’re not going to have work-life balance most of the time. That’s another unrealistic expectation.

In your report, you talk about ‘positive parenting.’ What is that?

Gawlik: The goal with positive parenting is building a relationship with your child. A lot of times we miss that relationship piece, or we put it second to what others are expecting of us.

For instance, everyone got very attached to our electronics during the pandemic. We were attached before, but this was on a whole new level because everything now was via Zoom, or via your phone. What that says to a kid is, “My parent is working. My parent is on their phone. I am a second-class citizen to that.” You have to think about how that makes a child feel.

What can parents do to overcome their burnout?

Melnyk: Quality playtime with your kids is so key. Not just being with them and listening with one ear and working on something else at the same time. It doesn’t have to be hours at a time. Whether it’s 10 minutes or 20 minutes, to give your child undivided attention is worth its weight in gold.

Adults need time to still do the things that bring them meaning and joy. If you’re not making time for them, you’re going to burn out much faster. Parents do a great job taking care of everybody else, but they often don’t focus on their own self-care. You can’t pour from an empty cup, and that’s what a lot of parents are trying to do.

If a parent is feeling stressed and overwhelmed, the idea of making a change may seem even more stressful and overwhelming. How do you break the cycle?

Gawlik: That can be tricky. When you get into this cycle of burnout — even a cycle of feeling like you’re not a good parent — it can be really hard to break out of it. You’re going to have to make an effort.

When you feel like you can’t literally put one more thing on, that’s when it comes back to shifting your priorities. What can you give up to make the mental capacity to do it? It’s going to look different for every parent.

My house is a mess 90% of the time and I’m not feeling bad about it anymore. I’ve just tried to reframe it. My kids are creative. Our toys are all over because the kids are playing with them and not sitting in front of a screen. I’m OK with the fact that my house is not clean all the time now because I can’t do that along with everything else that I’m doing and feel like I’m successful.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoStrack-Zimmermann blasts von der Leyen's defence policy

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoThe White House has a new curator. Donna Hayashi Smith is the first Asian American to hold the post

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoStefanik hits special counsel Jack Smith with ethics complaint, accuses him of election meddling

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDemocratic mayor joins Kentucky GOP lawmakers to celebrate state funding for Louisville

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTurkish police arrest hundreds at Istanbul May Day protests

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Police Arrest Columbia Protesters Occupying Hamilton Hall

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewsom, state officials silent on anti-Israel protests at UCLA

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPolice enter UCLA anti-war encampment; Arizona repeals Civil War-era abortion ban