Science

A mysterious, highly active undersea volcano near California could erupt later this year. What scientists expect

• Axial Seamount is the best-monitored submarine volcano in the world.

• It’s the most active undersea volcano closest to California.

• It could erupt by the end of the year.

A mysterious and highly active undersea volcano off the Pacific Coast could erupt by the end of this year, scientists say.

Nearly a mile deep and about 700 miles northwest of San Francisco, the volcano known as Axial Seamount is drawing increasing scrutiny from scientists who only discovered its existence in the 1980s.

Located in a darkened part of the northeast Pacific Ocean, the submarine volcano has erupted three times since its discovery — in 1998, 2011 and 2015 — according to Bill Chadwick, a research associate at Oregon State University and an expert on the volcano.

Fortunately for residents of California, Oregon and Washington, Axial Seamount doesn’t erupt explosively, so it poses zero risk of any tsunami.

“Mt. St. Helens, Mt. Rainier, Mt. Hood, Crater Lake — those kind of volcanoes have a lot more gas and are more explosive in general. The magma is more viscous,” Chadwick said. “Axial is more like the volcanoes in Hawaii and Iceland … less gas, the lava is very fluid, so the gas can get out without exploding.”

The destructive force of explosive eruptions is legendary: when Mt. Vesuvius blew in 79 AD, it wiped out the ancient Roman city of Pompeii; when Mt. St. Helens erupted in 1980, 57 people died; and when the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai volcano in Tonga’s archipelago exploded in 2022 — a once-in-a-century event — the resulting tsunami, which reached a maximum height of 72 feet, caused damage across the Pacific Ocean and left at least six dead.

Axial Seamount, by contrast, is a volcano that, during eruptions, oozes lava — similar to the type of eruptions in Kilauea on the Big Island of Hawaii. As a result, Axial’s eruptions are not noticeable to people on land.

It’s a very different story underwater.

Heat plumes from the eruption will rise from the seafloor — perhaps half a mile — but won’t reach the surface, said William Wilcock, professor of oceanography at the University of Washington.

Jason is a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) system designed to allow scientists to have access to the seafloor without leaving the ship.

(Dave Caress/MBARI)

The outermost layer of the lava flow will almost immediately cool and form a crust, but the interior of the lava flow can remain molten for a time, Chadwick said. “In some places … the lava comes out slower and piles up, and then there’s all this heat that takes a long time to dissipate. And on those thick flows, microbial mats can grow, and it almost looks like snow over a landscape.”

Sea life can die if buried by the lava, which also risks destroying or damaging scientific equipment installed around the volcano to detect eruptions and earthquakes. But the eruption probably won’t affect sea life such as whales, which are “too close to the surface” to be bothered by the eruption, Wilcock said.

Also, eruptions at Axial Seamount aren’t expected to trigger a long-feared magnitude 9.0 earthquake on the Cascadia subduction zone. Such an earthquake would probably spawn a catastrophic tsunami for Washington, Oregon and California’s northernmost coastal counties. That’s because Axial Seamount is located too far away from that major fault.

Axial Seamount is one of countless volcanoes that are underwater. Scientists estimate that 80% of Earth’s volcanic output — magma and lava — occurs in the ocean.

Axial Seamount has drawn intense interest from scientists. It is now the best-monitored underwater volcano in the world.

The volcano is a prolific erupter in part because of its location, Chadwick said. Not only is it perched on a ridge where the Juan de Fuca and Pacific tectonic plates spread apart from each other — creating new seafloor in the process — but the volcano is also planted firmly above a geological “hot spot” — a region where plumes of superheated magma rise toward the Earth’s surface.

For Chadwick and other researchers, frequent eruptions offer the tantalizing opportunity to predict volcanic eruptions weeks to months in advance — something that’s very difficult to do with other volcanoes. (There’s also much less likelihood anyone will get mad if scientists get it wrong.)

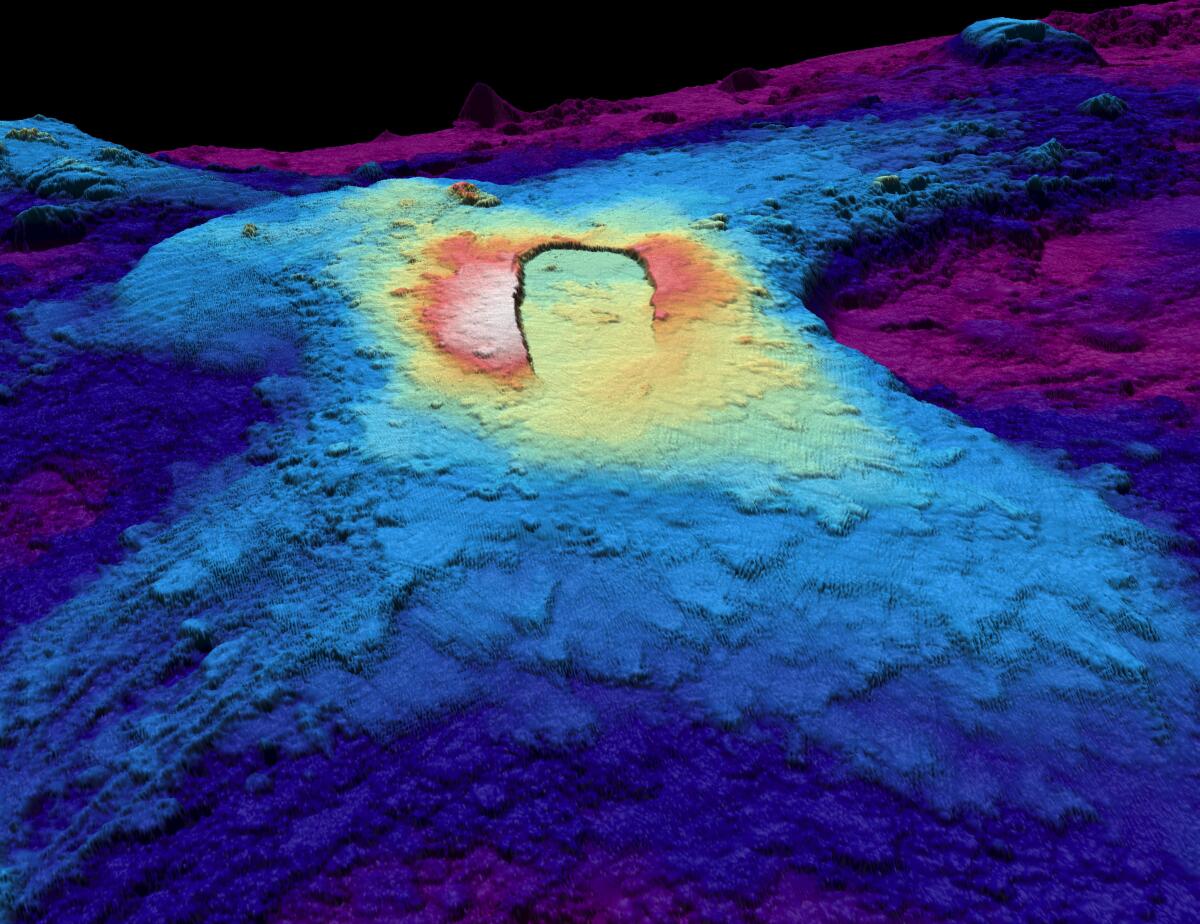

A three-dimensional topographic depiction showing the summit caldera of Axial Seamount, a highly active undersea volcano off the Pacific Coast. Warmer colors indicate shallower surfaces; cooler colors indicate deeper surfaces.

(Susan Merle / Oregon State University)

“For a lot of volcanoes around the world, they sit around and are dormant for long periods of time, and then suddenly they get active. But this one is pretty active all the time, at least in the time period we’ve been studying it,” Chadwick said. “If it’s not erupting, it’s getting ready for the next one.”

Scientists know this because they’ve spotted a pattern.

“Between eruptions, the volcano slowly inflates — which means the seafloor rises. … And then during an eruption, it will, when the magma comes out, the volcano deflates and the seafloor drops down,” Wilcock said.

Eruptions, Chadwick said, are “like letting some air out of the balloon. And what we’ve seen is that it has inflated to a similar level each time when an eruption is triggered,” he said.

Chadwick and fellow scientist Scott Nooner predicted the volcano’s 2015 eruption seven months before it happened after they realized the seafloor was inflating quite quickly and linearly. That “made it easier to extrapolate into the future to get up to this threshold that it had reached before” eruption, Chadwick said.

But making predictions since then has been more challenging. Chadwick started making forecast windows in 2019, but around that time, the rate of inflation started slowing down, and by the summer of 2023, “it had almost stopped. So then it was like, ‘Who knows when it’s going to erupt?’”

A deep-sea octopus explores the lava flows four months after the Axial Seamount volcano erupted in 2015.

(Bill Chadwick, Oregon State University / Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution / National Science Foundation)

But in late 2023, the seafloor slowly began inflating again. Since the start of 2024, “it’s been kind of cranking along at a pretty steady rate,” he said. He and Nooner, of the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, made the latest eruption prediction in July 2024 and posted it to their blog. Their forecast remains unchanged.

“At the rate of inflation it’s going, I expect it to erupt by the end of the year,” Chadwick said.

But based on seismic data, it’s not likely the volcano is about to erupt imminently. While scientists haven’t mastered predicting volcanic eruptions weeks or months ahead of time, they do a decent job of forecasting eruptions minutes to hours to days ahead of time, using clues like an increased frequency of earthquakes.

At this point, “we’re not at the high rate of seismicity that we saw before 2015,” Chadwick said. “It wouldn’t shock me if it erupted tomorrow, but I’m thinking that it’s not going to be anytime soon on the whole.”

He cautioned that his forecast still amounts to an experiment, albeit one that has become quite public. “I feel like it’s more honest that way, instead of doing it in retrospect,” Chadwick said in a presentation in November. The forecast started to garner attention after he gave a talk at the American Geophysical Union meeting in December.

On the bright side, he said, “there’s no problem of having a false alarm or being wrong,” because the predictions won’t affect people on land.

If the predictions are correct, “maybe there’s lessons that can be applied to other more hazardous volcanoes around the world,” Chadwick said. As it stands now, though, making forecasts for eruptions for many volcanoes on land “are just more complicated,” without having a “repeatable pattern like we’re seeing at this one offshore.”

Scientists elsewhere have looked at other ways to forecast undersea eruptions. Scientists began noticing a repeatable pattern in the rising temperature of hydrothermal vents at a volcano in the East Pacific and the timing of three eruptions in the same spot over the last three decades. “And it sort of worked,” Chadwick said.

Plenty of luck allowed scientists to photograph the eruption of the volcanic site known as “9 degrees 50 minutes North on the East Pacific Rise,” which was just the third time scientists had ever captured images of active undersea volcanism.

But Chadwick doubts researchers will be fortunate enough to videotape Axial Seamount’s eruption.

Although scientists will be alerted to it by the National Science Foundation-funded Ocean Observatories Initiative Regional Cabled Array — a sensor system operated by the University of Washington — getting there in time will be a challenge.

“You have to be in the right place at the right time to catch an eruption in action, because they don’t last very long. The ones at Axial probably last a week or a month,” Chadwick said.

And then there’s the difficulty of getting a ship and a remotely operated vehicle or submarine to capture the images. Such vessels are generally scheduled far in advance, perhaps a year or a year and a half out, and projects are tightly scheduled.

Chadwick last went to the volcano in 2024 and is expected to go out next in the summer of 2026. If his predictions are correct, Axial Seamount will have already erupted.

Science

After rash of overdose deaths, L.A. banned sales of kratom. Some say they lost lifeline for pain and opioid withdrawal

Nearly four months ago, Los Angeles County banned the sale of kratom, as well as 7-OH, the synthetic version of the alkaloid that is its active ingredient. The idea was to put an end to what at the time seemed like a rash of overdose deaths related to the drug.

It’s too soon to tell whether kratom-related deaths have dissipated as a result — or, really, whether there was ever actually an epidemic to begin with. But many L.A. residents had become reliant on kratom as something of a panacea for debilitating pain and opioid withdrawal symptoms, and the new rules have made it harder for them to find what they say has been a lifesaving drug.

Robert Wallace started using kratom a few years ago for his knees. For decades he had been in pain, which he says stems from his days as a physical education teacher for the Glendale Unified School District between 1989 and 1998, when he and his students primarily exercised on asphalt.

In 2004, he had arthroscopic surgery on his right knee, followed by varicose vein surgery on both legs. Over the next couple of decades, he saw pain-management specialists regularly. But the primary outcome was a growing dependence on opioid-based painkillers. “I found myself seeking doctors who would prescribe it,” he said.

He leaned on opioids when he could get them and alcohol when he couldn’t, resulting in a strain on his marriage.

When Wallace was scheduled for his first knee replacement in 2021 (he had his other knee replaced a few years later), his brother recommended he take kratom for the post-surgery pain.

It seemed to work: Wallace said he takes a quarter of a teaspoon of powdered kratom twice a day, and it lets him take charge of managing his pain without prescription painkillers and eases harsh opiate-withdrawal symptoms.

He’s one of many Angelenos frustrated by recent efforts by the county health department to limit access to the drug. “Kratom has impacted my life in only positive ways,” Wallace told The Times.

For now, Wallace is still able to get his kratom powder, called Red Bali, by ordering from a company in Florida.

However, advocates say that the county crackdown on kratom could significantly affect the ability of many Angelenos to access what they say is an affordable, safer alternative to prescription painkillers.

Kratom comes from the leaves of a tree native to Southeast Asia called Mitragyna speciosa. It has been used for hundreds of years to treat chronic pain, coughing and diarrhea as well as to boost energy — in low doses, kratom appears to act as a stimulant, though in higher doses, it can have effects more like opioids.

Though advocates note that kratom has been used in the U.S. for more than 50 years for all sorts of health applications, there is limited research that suggests kratom could have therapeutic value, and there is no scientific consensus.

Then there’s 7-OH, or 7-Hydroxymitragynine, a synthetic alkaloid derived from kratom that has similar effects and has been on the U.S. market for only about three years. However, because of its ability to bind to opioid receptors in the body, it has a higher potential for abuse than kratom.

Public health officials and advocates are divided on kratom. Some say it should be heavily regulated — and 7-OH banned altogether — while others say both should be accessible, as long as there are age limitations and proper labeling, such as with alcohol or cannabis.

In the U.S., kratom and 7-OH can be found in all sorts of forms, including powder, capsules and liquids — though it depends on exactly where you are in the country. Though the Food and Drug Administration has recommended that 7-OH be included as a Schedule 1 controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act, that hasn’t been made official. And the plant itself remains unscheduled on the federal level.

That has left states, counties and cities to decide how to regulate the substances.

California failed to approve an Assembly bill in 2024 that would have required kratom products to be registered with the state, have labeling and warnings, and be prohibited from being sold to anyone younger than 21.

It would also have banned products containing synthetic versions of kratom alkaloids. The state Legislature is now considering another bill that basically does the same without banning 7-OH — while also limiting the amount of synthetic alkaloids in kratom and 7-OH products sold in the state.

“Until kratom and its pharmacologically active key ingredients mitragynine and 7-OH are approved for use, they will remain classified as adulterants in drugs, dietary supplements and foods,” a California Department of Public Health spokesperson previously told The Times.

On Tuesday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the state’s efforts to crack down on kratom products has resulted in the removal of more than 3,300 kratom and 7-OH products from retail stores. According to a news release from the governor’s office, there has been a 95% compliance rate from businesses in removing the products.

(Los Angeles Times photo illustration; source photos by Getty Images)

Newsom has equated these actions to the state’s efforts in 2024 to quash the sale of hemp products containing cannabinoids such as THC. Under emergency state regulations two years ago, California banned these specific hemp products and agents with the state Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control seized thousands of products statewide.

Since the beginning of 2026, there have been no reported violations of the ban on sales of such products.

“We’ve shown with illegal hemp products that when the state sets clear expectations and partners with businesses, compliance follows,” Newsom said in a statement. “This effort builds on that model — education first, enforcement where necessary — to protect Californians.”

Despite the state’s actions, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors is still considering whether to regulate kratom, or ban it altogether.

The county Public Health Department’s decision to ban the sale of kratom didn’t come out of nowhere. As Maral Farsi, deputy director of the California Department of Public Health, noted during a Feb. 18 state Senate hearing, the agency “identified 362 kratom-related overdose deaths in California between 2019 and 2023, with a steady increase from 38 in 2019 up to 92 in 2023.”

However, some experts say those numbers aren’t as clear-cut as they seem.

For example, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that in a number of recent L.A. County deaths that were initially thought to be caused by kratom or 7-OH, there wasn’t enough evidence to say those drugs alone caused the deaths; it might be the case that the danger is in mixing them with other substances.

Meanwhile, the actual application of this new policy seems to be piecemeal at best.

The county Public Health Department told The Times it conducted 2,696 kratom-related inspections between Nov. 10 and Jan. 27, and found 352 locations selling kratom products. The health department said the majority stopped selling kratom after those inspections; there were nine locations that ignored the warnings, and in those cases, inspectors impounded their kratom products.

But the reality is that people who need kratom will buy it on the black market, drive far enough so they get to where it’s sold legally or, like Wallace, order it online from a different state.

For now, retailers who sell kratom products are simply carrying on until they’re investigated by county health inspectors.

Ari Agalopol, a decorated pianist and piano teacher, saw her performances and classes abruptly come to a halt in 2012 after a car accident resulted in severe spinal and knee injuries.

“I tried my best to do traditional acupuncture, physical therapy and hydrocortisone shots in my spine and everything,” she said. “Finally, after nothing was working, I relegated myself to being a pain-management patient.”

She was prescribed oxycodone, and while on the medication, battled depression, anhedonia and suicidal ideation. She felt as though she were in a fog when taking oxycodone, and when it ran out, ”the pain would rear its ugly head.” Agalopol struggled to get out of bed daily and could manage teaching only five students a week.

Then, looking for alternatives to opioids, she found a Reddit thread in which people were talking up the benefits of kratom.

“I was kind of hesitant at first because there’re so many horror stories about 7-OH, but then I researched and I realized that the natural plant is not the same as 7-OH,” she said.

She went to a local shop, Authentic Kratom in Woodland Hills, and spoke to a sales associate who helped her decide which of the 47 strains of kratom it sold would best suit her needs.

Agalopol currently takes a 75-milligram dose of mitragynine, the primary alkaloid in kratom, when necessary. It has enabled her to get back to where she was before her injury: teaching 40 students a week and performing every weekend.

Agalopol believes the county hasn’t done its homework on kratom. “They’re just taking these actions because of public pressure, and public pressure is happening because of ignorance,” she said.

During the course of reporting this story, Authentic Kratom has shut down its three locations; it’s unclear if the closures are temporary. The owner of the business declined to comment on the matter.

When she heard the news of the recent closures, Agalopol was seething. She told The Times she has enough capsules of kratom for now, but when she runs out, her option will have to be Tylenol and ibuprofen, “which will slowly kill my liver.”

“Prohibition is not a public health strategy,” said Jackie Subeck, executive director of 7-Hope Alliance, a nonprofit that promotes safe and responsible access to 7-OH for consumers, at the Feb. 18 Senate hearing. “[It’s] only going to make things worse, likely resulting in an entirely new health crisis for Californians.”

Science

There were 13 full-service public health clinics in L.A. County. Now there are 6

Because of budget cuts, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health has ended clinical services at seven of its public health clinic sites.

As of Feb. 27, the county is no longer providing services such as vaccinations, sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment, or tuberculosis diagnosis and specialty TB care at the affected locations, according to county officials and a department fact sheet.

The sites losing clinical services are Antelope Valley in Lancaster; the Center for Community Health (Leavy) in San Pedro, Curtis R. Tucker in Inglewood, Hollywood-Wilshire, Pomona, Dr. Ruth Temple in South Los Angeles, and Torrance. Services will continue to be provided by the six remaining public health clinics, and through nearby community clinics.

The changes are the result of about $50 million in funding losses, according to official county statements.

“That pushed us to make the very difficult decision to end clinical services at seven of our sites,” said Dr. Anish Mahajan, chief deputy director of the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

Mahajan said the department selected clinics with relatively lower patient volumes. Over the last month, he said, the department has sent letters to patients about the changes, and referred them to unaffected county clinics, nearby federally qualified health centers or other community providers. According to Mahajan, for tuberculosis patients, particularly those requiring directly observed therapy, public health nurses will continue visiting patients.

Public health clinics form part of the county’s healthcare safety net, serving low-income residents and those with limited access to care. Officials said that about half of the patients the county currently sees across its clinics are uninsured.

Mahajan noted that the clinics were established decades ago, before the Affordable Care Act expanded Medi-Cal coverage and increased the number of federally qualified health centers. He said that as more residents gained access to primary care, utilization at some county-run clinics declined.

“Now that we have a more sophisticated safety net, people often have another place to go for their full range of care,” he said.

Still, the closures have unsettled providers who work closely with local vulnerable populations.

“I hate to see any services that serve our at-risk and homeless community shut down,” said Mark Hood, chief executive of Union Rescue Mission in downtown Los Angeles. “There’s so much need out there, so it always is going to create hardship for the people that actually need the help the most.”

Union Rescue Mission does not receive government funding for its healthcare services, Hood said. The mission’s clinics are open not only to shelter guests, up to 1,000 people nightly, but also to people living on the streets who walk in seeking care.

Its dental clinic alone sees nearly 9,000 patients a year, Hood said.

“We haven’t seen it yet, but I expect in the coming days and weeks we’ll see more people coming through our doors looking for help,” he said. “They’re going to have to find help somewhere.” Hood said women experiencing homelessness are especially vulnerable when preventive care, including sexual and reproductive health services, becomes harder to access.

County officials said staffing impacts so far have been managed through reassignment rather than layoffs. Roughly 200 to 300 positions across the department have been eliminated amid funding cuts, officials said, though many were vacant. About 120 employees whose positions were affected have been reassigned; according to Mahajan, no one has been laid off.

The clinic closures come amid broader fiscal uncertainty. Mahajan said that due to the Trump administration’s “Big Beautiful Bill,” Los Angeles County could lose $2.4 billion over the next several years. That funding, he said, supports clinics, hospitals and community clinic partners now absorbing patients who previously went to the clinics that closed on Feb. 27.

In response, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors has backed a proposed half-cent sales tax measure that would generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually for healthcare and public health services. Voters are expected to consider the measure in June.

Science

Mobile clinic brings mammograms to women on Skid Row

Sharon Horton stepped through the door of a sky-blue mobile clinic and onto a Skid Row sidewalk. She wore a yellow knit beanie, gold hoop earrings and the relieved grin of a woman who has finally checked a mammogram off her to-do list.

It had been years since her last breast cancer screening procedure. This one, which took place in City of Hope’s Cancer Prevention and Screening mobile clinic, was faster and easier. The staff was kind. The machine that X-rayed her breast was more comfortable than the cold hard contraption she remembered.

Relatively speaking, of course — it was still a mammogram.

“It’s like, OK, let me go already!” Horton, 68, said with a laugh.

The clinic was parked on South San Pedro Street in front of Union Rescue Mission, the nonprofit shelter where Horton resides. Within a week, City of Hope, a cancer research hospital, would share the results with Horton and Dr. Mary Marfisee, the mission’s family medical services director. If the mammogram detected anything of concern, they’d map out a treatment plan from there.

Naureen Sayani, 47, a resident of Union Rescue Mission, left, discusses her medical history with Adriana Galindo, a medical assistant, before getting a mammogram on last week.

(Kayla Bartkowski / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s very important to take care of your health, and you need to get involved in everything that you can to make your life a better life,” said Horton, who is looking forward to a forthcoming move into Section 8 housing.

Horton was one of the first patients of a new women’s health initiative from UCLA’s Homeless Healthcare Collaborative at Union Rescue Mission. Staffed by third-year UCLA Medical School students and led by Marfisee, a UCLA assistant clinical professor of family medicine, the clinic treats mission residents as well as unhoused people living in the surrounding neighborhood.

The new cancer screening project arrives at a time of dire financial pressures on county public health services.

Citing rising costs and a $50-million reduction in federal, state and local grant and contract income, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health on Feb. 27 ended services at seven of 13 public clinics that provide vaccines, tests and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases and other services to housed and unhoused county residents.

Although Union Rescue Mission’s own funding comes mainly from private sources and is less imperiled by public cuts, the 135-year-old shelter expects the need for its services to rise, Chief Executive Mark Hood said.

Even as unsheltered homelessness declined for the last two years across Los Angeles County, the unsheltered population on Skid Row — long seen as the epicenter of the region’s homelessness crisis — grew 9% in 2024, the most recent year for which census data are available.

For many local women navigating daily concerns over housing, food and personal safety, “their own health is not a priority,” Marfisee said.

Those whose problems have become too serious to ignore face daunting obstacles to care. Marfisee recalled one patient who came to her with a lump in her breast and no identification.

In order to get a mammogram, Marfisee explained, the woman first needed to obtain a birth certificate, and then a state-issued identification card. Then she needed to enroll in Medi-Cal. After that, clinic staff helped her find a primary care physician who could order the imaging test.

Given the barriers to preventative care, homeless women die from breast cancer at nearly twice the rate of securely housed women, a 2019 study found. Marfisee’s own survey of the mission’s female residents found that nearly 90% were not up to date on recommended cancer screenings like mammograms and pap smears, which detect early cervical cancer.

To address this gap, Marfisee — a dogged patient advocate — reached out to City of Hope. The Duarte-based research and treatment center unveiled in March 2024 its first mobile cancer screening clinic, a moving van-sized clinic on wheels that it deploys to food banks and health centers, as well as to companies offering free mammograms as an employee benefit.

“In true Dr. Mary fashion, she saw the vision,” said Jessica Thies, the mobile screening program’s regional nursing director. After working through some logistical hurdles, the mission and City of Hope secured a date for the van’s first visit.

The next challenge was getting the word out to patients. Marfisee and her students walked through the surrounding neighborhood, went cot to cot in the women’s dorm and held two informational sessions in December and January to answer patients’ questions.

At the sessions, the team walked through the basics of who should get a mammogram (women age 40 or older, those with a family history of breast cancer) and the procedure itself. (“Like a tortilla maker?” one woman asked skeptically after hearing a description of the mammography unit.)

The medical students were able to dispel rumors some women had heard: The test doesn’t damage breast tissue, nor do the X-rays increase cancer risk. Others questioned a mammogram’s value: What good was it knowing they had cancer if they couldn’t get follow-up care?

On this latter point, Marfisee is determined not to let patients fall through the cracks.

Thirteen patients received mammograms at the van’s first visit on Wednesday. Within a week, City of Hope will contact patients with their results and send them to Marfisee and her team. She is already mentally mapping the next steps should any patient have a situation that requires a biopsy or further imaging: working with their case manager at the mission, calling in favors, wrangling with any insurance the patient might have.

“It’ll be a good fight,” Marfisee said, as residents in the adjacent cafeteria carried trays of sloppy joes and burgers to their lunch tables. “But we’ll just keep asking for help and get it done.”

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO7 days ago

Denver, CO7 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Florida4 days ago

Florida4 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Wisconsin3 days ago

Wisconsin3 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Oregon5 days ago

Oregon5 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling